Guidelines for Using Sources - Create

advertisement

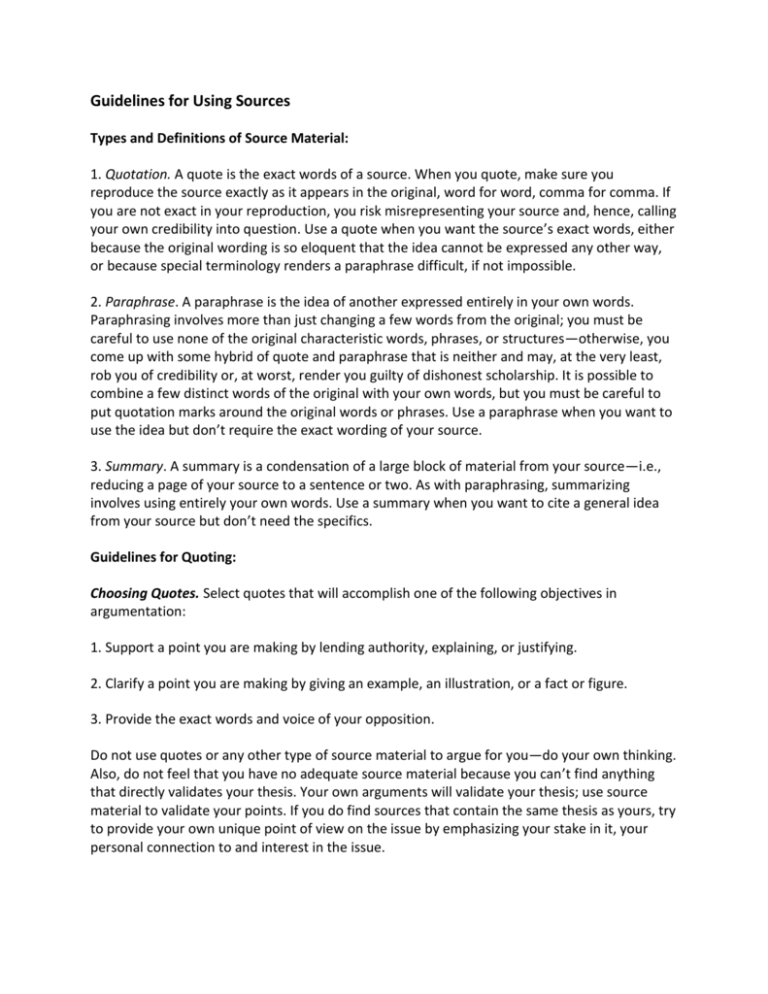

Guidelines for Using Sources Types and Definitions of Source Material: 1. Quotation. A quote is the exact words of a source. When you quote, make sure you reproduce the source exactly as it appears in the original, word for word, comma for comma. If you are not exact in your reproduction, you risk misrepresenting your source and, hence, calling your own credibility into question. Use a quote when you want the source’s exact words, either because the original wording is so eloquent that the idea cannot be expressed any other way, or because special terminology renders a paraphrase difficult, if not impossible. 2. Paraphrase. A paraphrase is the idea of another expressed entirely in your own words. Paraphrasing involves more than just changing a few words from the original; you must be careful to use none of the original characteristic words, phrases, or structures—otherwise, you come up with some hybrid of quote and paraphrase that is neither and may, at the very least, rob you of credibility or, at worst, render you guilty of dishonest scholarship. It is possible to combine a few distinct words of the original with your own words, but you must be careful to put quotation marks around the original words or phrases. Use a paraphrase when you want to use the idea but don’t require the exact wording of your source. 3. Summary. A summary is a condensation of a large block of material from your source—i.e., reducing a page of your source to a sentence or two. As with paraphrasing, summarizing involves using entirely your own words. Use a summary when you want to cite a general idea from your source but don’t need the specifics. Guidelines for Quoting: Choosing Quotes. Select quotes that will accomplish one of the following objectives in argumentation: 1. Support a point you are making by lending authority, explaining, or justifying. 2. Clarify a point you are making by giving an example, an illustration, or a fact or figure. 3. Provide the exact words and voice of your opposition. Do not use quotes or any other type of source material to argue for you—do your own thinking. Also, do not feel that you have no adequate source material because you can’t find anything that directly validates your thesis. Your own arguments will validate your thesis; use source material to validate your points. If you do find sources that contain the same thesis as yours, try to provide your own unique point of view on the issue by emphasizing your stake in it, your personal connection to and interest in the issue. Integrating Quotes into Your Text. Quotes should look like an integral part of your essay, not phrases or sentences dropped in and left floating in your text (because your teacher told you to put quotes in). By using the principles of PIE structure, you can easily tie down your quotes and make them work for your argument. Therefore, always introduce your quotes (providing the P of PIE) and follow them up with explanation/expansion/analysis. 1. Introducing quotes. Writers use three main techniques for introducing quotes: beginning with a lead-in, fitting the quote in as a syntactical unit of their own sentence, and preceding the quote with a complete sentence ending with a colon. A. Lead-ins. Some common lead-ins are “according to,” “a study by _____ found that,” and “in an interview with.” For example: According to John Warnock, in his introduction to the anthology Representing Reality, nonfiction works “may be defined as those that aspire to be both factual and true” (xvii). B. Quotes as syntactical units. This method is trickier because you have to make sure that the combination of your words and the source’s words creates a smooth, grammatically correct sentence. For example: Warnock’s assertion that literary nonfiction must “aspire to be both factual and true” helps us to distinguish literary nonfiction from both fiction and report (xvii). C. Sentence-colon introductions. This method works best when you have a block of text you want to quote, but you can also use it for shorter quotes when there is no smooth way of incorporating the quote into your own sentence. For example: Warnock justifies his definition of literary nonfiction by explaining that truth and fact are not the same thing: “By itself, a list of facts may be accurate, but such a list lacks the kind of truth that may be found in works of ‘history, or biography, or documentary” (xvii). Note: Never use one introduction for several quotes, and don’t string quotes together one after another. 2. Following up quotes. An introduction is rarely sufficient for making the point illustrated by the quote. In fact, the introduction is usually no more than a statement of the point. Never assume that the connection between your quote and your argument is self-evident; if you do, you force your readers to fill in the necessary connections (which they may do in a way you don’t intend) and do the work that you, as the writer, are responsible for. For example, let’s go back to the last quote in the section above. If left as is, without follow-up explanation, the quote may leave the reader with a number of questions, such as, “Okay, facts are not necessarily true, but what does Warnock think is truth, and how do histories, etc., provide that truth?” Since this distinction is especially important in the argument in which it is found, the writer must anticipate this question and explain it, or his/her argument will fail to be convincing. Hence, the writer follows the quote with the explanation below: Truth, as John Warnock explains, is more than just an assemblage of facts but an arrangement and interpretation of them that “represent a state of affairs” or an expression of human experience that is familiar to readers (xvii). Consequently, a biography does more than just present the verifiable events in a person’s life but tries to show what it was like to live that life and suggests what that life means to the rest of us. Note that the above follow-up does not merely paraphrase the quote. It sets the quote within the context of the discussion at hand and provides an example to help explain it. Some quotes may need the kind of interpretation that a paraphrase provides; however, most, if not all, quotes will require further explanation that connects the quote to the point of the argument. Mechanics of Quoting. Handle the mechanics of inserting quotes into your text correctly. If you make mistakes, your reader may become confused, in some cases, or decide you don’t know what you’re doing, in others. 1. To block or not to block. A. If your quote is no longer than four typed lines of prose or three lines of poetry, you may incorporate the quote into your own text, using quotation marks before and after the quote to set it off (but remember that lines of poetry or lyrics require slashes to indicate line ends). However, proofread carefully to make sure you have included both sets of quotation marks— opening marks but no closing marks confuse the reader as to where the quote ends. B. Quotes longer than four typed lines of prose or three lines of poetry (or lyrics) must be set off in block form, which involves indenting the block five spaces and leaving a double-space before the first line and after the last line to set it off from your own text. Some people also argue that a block quote should be single-spaced. 2. Making changes in quotes. In general, the rule is that you must reproduce a quote exactly as it appears in the original. However, occasionally you may need to make slight changes to better fit the quote into your text. The following are permissible changes: A. Underlining or italicizing for emphasis. If you want to emphasize a word or phrase in a quote because it has particular importance to your point, you may do so as long as you add the phrase (emphasis added) at the end of the quote after the quotation marks and before the ending punctuation. According to the Russian writer Iurii Afanas’ev, “Only new historical research, free from ideological dogma, can help us comprehend the integrity and vastness of our past, really free ourselves from Stalinism, and recreate our social identity” (emphasis added) (548). B. Putting brackets around changed or added words. If it is necessary to change a word, such as substituting a name for a pronoun or changing the tense of a verb, you may do so as long as you indicate it with brackets around the changed word. Such changes should be made for clarity or grammatical consistency, not to change the meaning of the quote. Furthermore, such changes should extend for only a word or two, not whole parts of the quote. Remember that brackets [ ] are not the same as parentheses ( ). If your typewriter or computer does not have keys for brackets, you will need to handwrite them in. In an interview in Omni, Morris Berman asserts that “the Gulf War is the latest manifestation of this tragedy [the split between Self and Other in Western thinking]” (64). C. Using ellipses to indicate omissions in quotes. If you need to leave out part of a quote, either because it is irrelevant to your point or because you need to omit words in order to create a grammatical blending of your words and the quote, you may do so as long as you use the ellipsis marks, three spaced periods (. . .), to show that you have omitted words. However, ellipsis marks can work only if you are omitting no more than a line or two. If more than a few lines are omitted between one part of the quote and the other, use your own words rather than ellipsis marks to separate the quotes (in other words, make two separate quotes). Euphemistic language, far from being a relic of Victorian times, continues today, for “whenever the speech community must discuss anything it deems unpleasant, the discussion. . . is carried on in the elegant vocabulary bestowed on English by the Normans” (Farb 89). 3. Punctuating quotes. A. Quotation marks. Use double quotation marks (“) to indicate all quoted material except when a quote occurs within another quote. In that case, use single quotation marks (‘) to indicate the inside quote. For example: In discussing the development of speech in children. Peter Farb mentions “Carolus Linnaeus, the eighteenth-century inventor of the system of classification of living things still in use, [who] listed Homo ferns, Latin for ‘wild man,’ as a subdivision of our species. Homo sapiens” (270). B. End punctuation. The general rule is that all commas and periods go inside the ending quotation marks, all semicolons and colons outside, and question marks and exclamation marks go inside if part of the quote, outside if not. However, if you need to put in a parenthetical citation of author and page number, the rule changes. The period or comma will always go outside the parentheses (see above example), and therefore no period or comma appears at the end of the quote. However, if the above quote had ended in a question mark or exclamation mark, it would have gone inside the quotation marks, followed by the parenthetical citation and the end period. For example: Farb asks, “Is not our preoccupation with developing an international tongue based on false premises?” (366). C. Eliminating punctuation in quotes. In general, reproduce the exact punctuation of the original source; however, you may leave off punctuation that occurs at the end of the quoted material, such as semicolons, colons, and commas, if they do not fit your own sentence. A period that occurs at the end of the quote is placed after the parenthetical citation to act as a period for both the quote and your sentence. You may also eliminate a capital letter that begins the sentence in your quote if your quote is a syntactical part of your own sentence. Guidelines for Paraphrasing: A paraphrase may contain none of the original wording or grammatical structures of your original source. Because it is entirely your own words, it need not be identified by quotation marks or indenting. However, you do need to indicate to your reader where your paraphrase begins, so use a lead-in technique such as one of those used for quotes (see above discussion). A good way to lead into a paraphrase is to begin, “According to report done on gender and memory, reported by Jane Flax in her essay “Re-Membering the Selves: Is the Repressed Gendered,”—and lead into the paraphrase. You also need to document the source of your paraphrase. The parenthetical citation should appear at the end of the paraphrased material, just as it marks the end of quoted material. But paraphrasing can be tricky. The author’s original sentence rhythms and phrasings can be seductive, especially if you don’t quite grasp the idea or the way it fits into your own argument. Look at the following example: Original: The British are a mixed race, but the non-Teutonic goddess-worshipping strains are the strongest. This explains why the poets’ poetry written in English remains obstinately pagan. The Biblical conception of the necessary supremacy of man over woman is alien to the British mind: among all Britons of sensibility the rule is “ladies first” on all social occasions. The chivalrous man dies far more readily in the service of a queen than of a king: self- destruction is indeed the recognized proof of the grand passion. --from Robert Graves, The White Goddess, p. 406 Paraphrase #1: Although they are a mixed race, the British still exhibit strong non-Teutonic goddessworshipping characteristics. English poetry is obstinately pagan, and the Biblical idea of male supremacy is foreign to the British mind. A chivalrous man will sacrifice his life far more readily for his queen than for his king, for self-destruction is seen as the proof of grand passion (Graves 406). This paraphrase runs dangerously close to plagiarism because it uses too many words of the original and follows too closely the sentence patterns of the source. The writer has little thought about what the original passage is saying and has probably not incorporated its idea very well into his main idea. Now look at a better paraphrase of the above original: Paraphrase #2: The most prominent examples of Britain’s heritage of pagan goddess-worship, and its continued influence over the British people, are to be found in both their writings and their social behavior. In conception at least, women are not inferior beings but persons to be respected and even to be deferred to. In love-poetry they become objects of worship, and the woman of power can inspire the greatest acts of heroism and selfsacrifice (Graves 406). This paraphrase copies none of the language or sentence patterns of the original and clearly shows how the writer has understood the passage, indicating how it connects to the writer’s thesis. Therefore, it is a better example of what a paraphrase ought to be. Guidelines for Summarizing: The guidelines for summarizing are essentially the same as for paraphrasing. Summaries need to be introduced to show where they begin, documented with a parenthetical citation at the end, and worded in language which is entirely the writer’s own and not that of the source. Guidelines for MLA Documentation: The revised MLA system for documenting primary and secondary sources consists of two parts: parenthetical in-text citations and a works cited page. 1. Parenthetical Citations. A citation consists of the author’s last name and the page or pages containing the source material quoted, paraphrased, or summarized. This citation is placed within parentheses before the end punctuation. An example of a parenthetical citation is the following: (Graves 406) Note that the citation contains no punctuation and no p. before the page number. If the quote or paraphrase had covered material on more than one page, the citation would have looked like the following: (Graves 406-07) If the source has no author listed, then the citation should use a shortened version of the book or article title, such as the following, taken from a journal: “Re-Membering” (93) If you include the author’s name in your introduction to the quote or paraphrase, the citation may contain only the page number of numbers and omit the author’s name. 2. Works Cited Page. The works cited page is a separate page included at the end of your essay. It is titled Works Cited, centered at the top of the page. Remember these important rules as you prepare your works cited page: A. Arrange works in alphabetical order according to author’s last name. If no author is listed, use the first important word in the title (use article title for articles, not magazine, journal, or newspaper title). B. Double-space both within each entry and between entries. C. Begin the first line of each entry at the left margin of your page. Each subsequent line of the entry is indented five spaces. (For those of you familiar with journalism terms, this is called a “hanging paragraph.”) D. Do not number your entries. E. Use correct punctuation and order for entries. Developed by Carol Nowotny-Young University of Arizona Writing Program – 2002