SummaryPaper and Notemaking - Laura Sato`s Digital Portfolio

advertisement

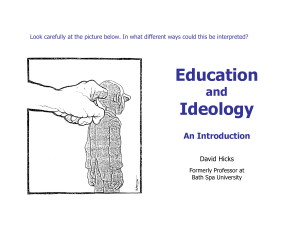

LDR 101I How Do I Look? Fall 2015 Smith Notemaking/Close Reading and Summary Paper (for “Practices of Looking”) Due date: September 15 Summary: Summarize the section we are reading from Practices of Looking in outline form or in narrative form (full sentences/paragraphs). Try to pick out and paraphrase or quote directly the thesis of the introduction and the main ideas of each section. When you refer to specific ideas, either in paraphrase or by quotation, include the page numbers at the end of the line or the sentence. [I realize that these are not Chicago style citations/footnotes; we will work on those in a few weeks. For now I want you to get used to citing the page numbers of your sources.] Notemaking: Submit the notes you made as you read the text and/or used as you wrote your summary, even if they are on your copy of the text. Please make a list (either in your notes or at the end of the paper) of any terms, names, or ideas that you needed to look up in order to understand the text. This assignment relate to the following learning objectives: Summarize and explain the main ideas of a text, speech, doctrine, principle or belief. Laura Sato Professor Katherine Smith LDR 101: How do I look? September 13, 2015 Summary of “Practices of Looking-Images, In the chapter, “Images, Power, and Politics,” the authors explain about images and the power that they hold. They separated this via six sections. The sections are Representation, Myth of Photographic Truth, Images and Ideology, How We Negotiate the Meaning of Images, Value of Images, and Image Icons One common theme that can be found throughout the chapter is one of power. It describes looking as being a, “social practice” and “To be made to look, [or] to try to get someone else to look at you…entails a play of power” (9). From these six sections, you can dissect the thesis that can be found on page 46, “By looking at and engaging with images in the world, we influence the meanings and uses assigned to the image…” (46). The first section that is covered in the chapter is representation. Representation is referred to as being, “the use of language and images to create meaning about the world around us” (12). They contrast this to mimesis which is a “reflection” of a material (12). We construct meaning of things through our representation of them (12). The example given is of two similar paintings, which is a Still Life by Henri Horace Roland de la Porte and Still Life with Dralas by Marion Peck. Although they are stylistically the same, they do not portray the same meaning since Marion Peck added faces to show an energy that she found in the painting. The painting illustrates how we need to look for underlying meanings of images that are round all around us. Next, The Myth of Photographic Truth is the idea that a photograph that is taken of the world is False. This is due to the photographer’s ability to manipulate the frame and edit the picture. With current technology, photography is becoming more subjective. In the photograph Trolley- New Orleans, we see people of all races and this evokes emotions about segregation and racism. This relates back to a quote that is found earlier which states how “photographs always indicate a kind of mortality, evoking death in the moments in which they seem to stop time” (18). Emotions can be gained by looking at photographs. Although, photographs can be edited, there can still be some truth that can be found in the image. In the third section, “Images and Ideology”, there is a discussion about how images are produced with the social issues and ideologies of many cultures. Ideologies are defined as being “systems of beliefs that exist within all cultures” (23). The chapter explains how we often use these tools of looking automatically, without giving them much thought (26). These images are based off of the current conventions (26). The Newsweek cover on June 27, 1994, shows how “the meaning of images can change dramatically when those images change social contexts. In this case, O.J. Simpson’s mug shot illustrated a villain that is a danger to society. “How We Negotiate the Meaning of Images,” demonstrates how we in current times decipher the meaning of certain images. We often look at context as a way to discover the meaning of an image. The meaning can also be found by doing research about the author as shown by the painting, Butterfly by Yue Mingun. The next section, “The Value of Images,” acts as a bridge from the social views of the time and the meaning of the work. On page 34, it states that, “Some of the information we bring to reading images has to do with what we perceive their value to be in a culture at large” (34). This illustrates why many painters like Vincent Van Gogh could not sell a single painting in his lifetime. Now people want to have his art and it sells for millions. At Van Gogh’s time, he was a revolutionary artist leading the way of the impressionists. Therefore, his art was not respected by his culture. Now however, he is known as being one of the most expressive painters in the world. The last section of the book speaks of image icons. An icon is an image that refers to something outside of its individual components. These however do not have to represent universal values. They often have “meanings are always historically and contextually produced” (40). An example they give is of the Madonna and child. It is only highly regarded in Western and Christian societies. However, it is thought to be a universal value due to its far reach. Laura Sato Close Read Notes- Process of Looking: An Introduction to Visual Culture Images, Power, and Politics “Looking is a social practice.” Through looking, touching, and hearing we negotiate our social relationships and meaning. We do not “look” at anything without participating in a practice formed by a variety of factors, including the historical moment, social meaning, and intent of the creator. Practices of looking are also formed by power relationships. The act of choosing to look or not to look is an act of power. We engage in the practices of looking every day, with an ever-increasing amount of visual artifacts permeating most cultures. Weegee (Arthur Felig), The First Murder, before 1945: image of women and schoolchildren looking at a murder scene in the street dramatically draws our attention to the practices of looking. He calls attention to both act and looking at the forbidden scene and the capacity of the still camera to capture heightened fleeting emotion. Photograph of Emmett Till’s brutalized body in his casket, 1955: wide spread photograph of a boy who was murdered during the beginning of the civil rights movement in the United States. Till’s mother insisted on having an open-casket funeral. She allowed photography so everyone could see the violence enacted on her son. This graphic photograph was a major catalyst of the civil rights movement. 1) Representation Representation is the use of language and images to create meaning about the world around us. Systems of representation can be analyzed through methods borrowed from linguistics and semiotics. Book argues “that we make meaning of the material world through understanding objects and entities in their specific cultural contexts. Process of understanding the meaning of things takes place in part through our use of written, gestural, spoken, or drawn representations. Mimesis is a concept that understands representation as a process of imitating or mirroring the real. Henn Horace Roland de la Porte, Still Life, c. 1965: an array of food and drink is carefully arranged on a table and painted with attention to each minute detail. This image is a reflection of this particular scene. Porte was a student of Jean-Baptiste-Simone Chardin who was fascinated with 17th century Dutch painter. Marion Peck, Still Life With Dralas, 2003: a contemporary pop surrealist painter and interprets Porte’s still life to contain an anthropomorphic energy and brings it to life with comic little faces. Rene Magritte, The Treachery of Images, 1928-29: painting depicts a pipe with the line in French, “This is not a pipe.” One could argue that he is making a joke. However, he is pointing to the relationship between words and things. Magritte asks us to consider how labels and images produce meaning yet cannot fully invoke the experience of the object. Magritte contrasted mimesis and representation. Foucault explains, multiple and the layers of representation pile on one another to the point of incoherence. Today we are surrounded by images that play with representation unmasking our initial assumptions and inviting us to experience meanings beyond the obvious. 2) The Myth of Photographic Truth We perceive photographs to be an unmediated copy of the real world. Positivism is the theory that scientific knowledge (empirical data), is the only authentic knowledge. Machines (such as cameras) were thought to be more reliable than humans to provide this data and knowledge. However, images can be altered, reflect only one instant in a situation, and can be taken out of social and historical context Roland Barthes considered photographic truth a myth because he is at odds with the positivist understanding of truth as something that can be independently verified. Robert Frank, Trolley-New Orleans, 1955: the faces of the passengers each look outwards with different expressions, responding in different ways to their lives, their journey. In all images we can discern multiple levels of meaning. Barthes gives us a system for interpreting two levels of meaning in examining an image: denotative meaning is an image’s literal, descriptive meaning Connotative meaning relies on the cultural and historical context and the viewer’s shared experience and knowledge of these contexts. Trolley—New Orleans: denotative meaning is “passengers on a trolley,”; connotative meaning race relations in the 1950s. Barthes’s theory of myth goes beyond the myth of photographic truth. Myths are how meanings, formed by hidden sets of rules and conventions, are made to seem universal but are in reality specific to certain groups. Through myth, the connotative meaning is made to seem natural or denotative. Nancy Burson, First and Second Beauty Composite, 1982: used early digital technologies to make a composite of images of Bette Davis, Audrey Hepburn, Sophia Loren, Grace Kelly, and Marilyn Monroe that contrasts Jane Fonda, Jacqueline Bisset, Diane Keaton, Brooke Shields, and Meryl Streep. These two images evoke the idea that different looks are favored and become the standard in different eras. 3) Images and Ideology Ideology contributes to the construction of an image’s meaning. An ideology is a system of belief in a culture. Ideologies are shared, extensive sets of patterns and beliefs that guide human interaction and behavior. In the modernist period, dominant ideologies, such as that of positivism, were typically accepted as facts, whereas in postmodernity, people have tended to recognize that ideologies are at play and are that meanings are always connotative. There is no one “natural” ideology. The places where these ideologies intersect and collide inform our practices of looking. Carta de visite of George Armstrong Custer, 1860s: shows image and signature and affirms individuality and shows the way photography was a part of life. O. J. Simpson’s mugshot, Time, June 27, 1994: the social convention of the mugshot (guilt and shame), combined with the historical convention (villainy and deviance), resulted in the controversial use of an altered photograph that reflects the interplay of ideologies. 4) How We Negotiate the Meaning of Images Smiley Face: emerged in 1960 has largely been understood as a symbol of happiness. Yue Minjun, Butterfly, 2007: exaggeration of smiles, the distorted faces, horned heads, strange and naked red bodies he juxtaposed with colorful butterflies. You can learn about connotations from artist. Charles Sanders Peirce theorized that languages and thought are processes of sign interpretation. Semiotic model: the sign is the word or image, not the relationship between the image and meaning, and the interpreted meaning, with the object itself separate from the sign. Peirce also distinguished between three types of signs: iconic, indexical, and symbolic. Iconic signs resemble the object itself. Symbolic signs, such as the word cat for the actual animal cat, do not resemble the object itself, are arbitrary, and require prior knowledge of a system to make sense. Indexical is valuable to the study of visual culture because of its explanation of the sign’s relationship to interpret; the two have co-existed at the same place at one time. Fingerprints are indexical signs; they signify that a specific person existed in that place at one time. Photographs are iconic (they resemble the object photographed), but they are also indexical, providing evidence that the object existed at one time in a specific place. Advertising is a prime example of all three types of signs at play to create multiple meanings. Barthes’s semiotic model demonstrates how an image can have multiple meanings and how signs (such as the dove, symbolic of peace) that seem to be natural are in fact constructed. Semiotics: study of signs, symbols, and how we interpret them. According to Ferdinand de Saussure, meanings change according to context and the rules of language. Barthes’s semiotic model is based on Saussure’s work, where Signifier = Image/Sound/Word; Signified = Mental Concept and together; Signifier + Signified = Sign. Anti-smoking ad: dependent on our knowledge that cowboys are disappearing from the American landscape, that they are cultural symbols of a particular ideology of American expansionism and the frontier that began to fade with urban industrialization and modernization. Illustrates the changing role of men. Marjane Satrapi, frames from Persepolis, 2003: she depicts herself as a young girl who with her classmates has been obliged to wear a veil to school. Creates iconic signs of the young women and their veils-we know how to read these images because they resemble what they are representing. In stark black and white, the veils command visual attention within the frame (homogenizing visual effect of the girls’ veils). Land Rover Ad: uses text, which suggests that the car can be new as well as a classic, to shape how viewer-consumers will see the image of the art itself. 5) The Value of Images Although monetary value is often assigned to well-known images (such as the work of van Gogh or Pollock), cultural, social, and political values are also assigned in different social contexts. Vincent van Gogh, Irises, 1889: achieved a new level of fame when it was sold for an unprecedented price of $53.8 million to the Getty Museum in Los Angeles. The monetary value of is derived from the aesthetic value of the painting, social myth, the scarcity of his works, the authenticity of the painting, representative of the impressionist style, the media attention, and exposure in educational and mass media contexts. The ability to mass reproduce art, not only on canvases but also on coffee mugs, neckties, and posters, also contributes to the value of an artifact. In van Gogh’s case, the many reproductions of his work in these and other forms add to the social value of his original works instead of detracting from it. 6) Image Icons Tiananmen Square, Beijing, China, 1989: the value of this image is based in part of its capturing of a special moment (depicts key moment in event when media coverage was restricted) and the speed it was transmitted around the world to provide information about the event. Photograph of protestors at April 9, 2008, San Francisco protest against decision to hold Summer Olympics in Beijing: has value through its speed of transmission, its informative value, and its political statement. An icon is an image that refers to something outside of its individual components, something (or someone) that has great symbolic meaning for many people. They are culturally and historically constructed. Mother and child demonstrates that the use of mother and child in paintings (from Joos van Cleve and Raphael) are representations of motherhood in a specific time and place that are perceived to be universal. Dorthea Lange, Migrant Mother, California, 1936: removal of context actually contributes to the universality of the icon of motherhood. Andy Warhol, Marilyn Diptych, 1962: shows Marilyn Monroe as an icon of entertainment, glamour, and commodity. Madonna and child icon represents Christian and Western traditions. Icons used across cultures can be interpreted in different ways. The history of the motherhood icon illustrates the complexity of icons and their interpretations. In order to “read” the image, one must consider the historical, cultural, and social codes and contexts within the image, the context of its presentation, and the formal technique of the image itself.