The number of FASB`s revenue-recognition rules has grown to more

advertisement

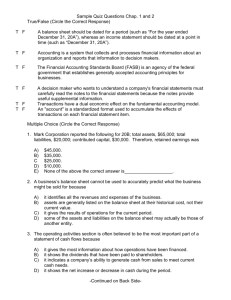

Revenue recognition By Graham Holt The International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) and US Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) recently published a discussion paper setting out a joint approach for the recognition of revenue. Revenue-recognition requirements in US GAAP differ from those in International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRSs) and both are considered in need of improvement. A major cause of complexity appears to be the overabundance of FASB revenue-recognition rules in comparison with the IASB standards. Many of the standards are industry-specific and some can produce conflicting results for similar transactions. The number of FASB's revenue-recognition rules has grown to more than 100 standards, plus rule exceptions addressing over 20 different industries. Although IFRS contain fewer standards on revenue recognition, its standards have conflicting principles, and can be difficult to understand and apply beyond simple transactions. Both bodies of standards have led to diversity in practical application and a skewing of economic reality. The boards' objective is to develop a single revenue model that can be applied consistently, regardless of industry. Under the proposed standard a company would recognise revenue when it satisfies a performance obligation by transferring goods and services to a customer as contractually agreed. This principle is similar to many existing requirements and the boards expect that most transactions would remain unaffected. Revenue recognition is an area susceptible to a range of errors and possibly fraud. The proposed model applies to contracts with customers. The discussion paper defines a contract as 'an agreement between two or more parties that creates enforceable obligations'. A customer is defined as 'a party that has contracted with an entity to obtain an asset (such as a good or service) that represents an output of the entity's ordinary activities.' Agreements do not have to be in writing to be a contract. In principle the model could apply to all contracts, but there is uncertainty about whether it is appropriate for some financial instruments; insurance contracts; and leasing contracts. In a contract, an entity receives consideration (rights) from, and promises to transfer assets (performance obligations) to, a customer. Under the proposed model, the rights and obligations give rise to a net contract position and revenue is recognised when a contract asset increases or a contract liability decreases as an entity satisfies its performance obligations. The key change from the current model is that revenue will be based on the changes in contract assets and liabilities. All contracts (with the possible exception of the above) would be analysed into contract assets and contract liabilities. Revenue would only be recognised when either the net contract liability is reduced or the net contract asset has increased, both as a result of the entity discharging its contract liabilities by performance. Revenue should only be recognised on the fulfilment of a performance obligation under a contract. The transfer of control evidences fulfilment. Example 1 Entity A agrees to sell Entity B a product for £30,000, which is 'the transaction price'. Entity A has an obligation (and therefore a liability) to provide a product worth £30,000 and a right to receive payment (and an asset of £30,000). The net position is zero. The position changes when Entity A completes the sale and has no further obligation. Entity A still has an asset of £30,000 (the money due from the customer), but no further obligation and therefore a liability of zero. The net position in the contract as a result of the satisfaction of the performance obligation is now an asset of £30,000, and so the business would recognise £30,000 revenue. Challenges and changes The focus on the transfer of assets via control may change many existing revenue models. Current revenue standards consider other criteria, such as when risks and rewards are transferred to the customer, or when collectability is reasonably assured. The proposed model could have a considerable impact on the timing of revenue recognition if control of an asset transfers at a different time than the transfer of risks and rewards. Collectability could potentially impact the measurement of the contractual rights, but may not by itself preclude revenue recognition. In some cases, the transfer of control of an asset coincides with the transfer of risks and rewards of owning an asset, but in other cases it may not. This proposal may present challenges for companies that do not determine the satisfaction of a performance obligation by evaluating the transfer of control of assets to customers. It is difficult to assess whether the paper contains sufficient information about how control would be determined in practice to decide whether the principles can be applied consistently to complex transactions such that their substance is articulated. The paper considers control to pass only when the goods or services are delivered to the customer, but it is arguable that, for bespoke and customised items, the specification and output of these items may be controlled from the outset by the customer, and so the customer is able to restrict the control the supplier has over the asset. Transfer of control may be difficult to determine even in many quite simple service contracts, and it is apparent entities can interpret the notion of control in very different ways. Although this seems conceptually straightforward and follows the IASB's framework 'balance sheet' approach. Entities are going to have to identify what performance obligations have to be satisfied (the delivery of either a good or a service) and allocate a value to each. Additionally, construction contracts, which are currently covered by IAS 11, Construction contracts, fall within the scope of this project. Thus, it will be important to identify when performance has been satisfied, as it could take place over a period of time, or at the very end of a project. The IASB acknowledges that there are several areas where further consideration is required. This includes the measurement of contract assets, how much someone is going to pay the entity to satisfy the obligations, the impact of any changes to contractual terms, how revenue will be presented, and a decision on whether and how the fair value of certain performance obligations should be measured. Revenue for construction contracts would be recognised during construction, only if the customer controls the item as it is constructed. This could lead to revenue being recognised later than at present. However, if construction activities continuously transfer assets to a customer, then the proposed model would not significantly change the present IFRS-based practice of recognising revenue for construction-type contracts during the construction phase. The timing of revenue recognition could be close to current practice, or considerably different, depending on the application of the key concepts, such as when an asset is transferred and when the customer has control of the asset. Guidance on the transfer of control needs to be provided in order to make the principles operational. A single, contract-based revenue-recognition model will always allow entities to manage the timing of revenues by the changing of the contract terms, but strict application of legal form of the contract will result in differing treatments, depending on the laws of different countries. Performance obligations must be identified and separated. For example, a warranty, or a guarantee, or a right of return may be identified as separate performance obligations. A sale with a warranty involves two distinct performance obligations. First, there is the sale of the goods specified in the contract. Second, there is the obligation to do whatever the warranty specifies. The criteria in existing standards will no longer be relevant. Companies will separate the performance obligations in a contract whenever a company transfers the promised assets to a customer at different times. The transaction price will be allocated to separate performance obligations. Current practices of accruing warranty costs at the time of revenue recognition may be eliminated. Instead, a warranty may be considered a performance obligation to which a portion of the total consideration will have to be allocated and then recognised as revenue when the warranty obligation is satisfied. The satisfaction of the warranty obligation may not necessarily occur evenly over the contract life. Rights of return are accounted for using an estimated failed sale model where, if certain conditions are met, revenue is reduced to reflect estimated returns. The boards are uncertain as to whether rights of return should be treated as either a performance obligation or a failed sale. Example 2 An entity sells an item with a warranty for £20,000. If it sold the item and the warranty separately it would cost £18,000 for the goods and £3,000 for the warranty. The overall transaction price of £20,000 would be allocated prorata to the two distinct obligations. The sale of goods element would be £17,143, and the amount allocated to the warranty element would be £2,857. The business would recognise revenue of £17,143 on the sale of the goods and recognise revenue of £2.857 relating to the warranty over its life. Next steps The boards have proposed a single revenue recognition model that can be applied consistently across a range of industries and geographical regions. The boards will review the comments received on this discussion paper and modify or confirm their preliminary views. They will then use the views to develop for public comment an exposure draft of a comprehensive standard on revenue recognition. Graham Holt, ACCA examiner and principal lecturer in accounting and finance, Manchester Metropolitan University Business School TASKS I. Translate the highlighted words and parts of sentences II. Multiple choice questions 1) The discussion paper may have a significant effect particularly on accounting for: a) b) c) d) Sale of services Long-term construction contracts x Leases Financial instruments 2) Why did the IASB and FASB feel the need to issue a discussion paper on revenue recognition? a) b) c) d) The Boards were reacting to recent scandals US GAAP was too simplistic x IAS 18 'Revenue' was too complex Both IFRSs and US GAAP had led to a diversity in practical application 3) What is the objective of the Boards in producing the discussion paper on revenue recognition? a) b) c) d) To change the way in which long term contracts are accounted for To recognise revenue sooner To assist entities in enhancing profitability To develop a single revenue model that can be applied consistently regardless of industry x 4) Under the proposed model, what is the principle behind the recognition of revenue? a) Revenue is recognised when either the net contract liability is reduced or the net contract asset has increased x b) Revenue is recognised when the contract is signed c) Revenue is recognised when either the net contract liability is increased or the net contract asset has reduced d) Revenue is recognised at any time before control is achieved 5) The transfer of assets in the revenue recognition model proposed by the discussion paper is based upon what principle? a) b) c) d) Collectability Passing of the risks and rewards of ownership Passing of control of the asset x Passing of title in law