Becoming A Resilient Newcomer: Supervisory Influence Via

advertisement

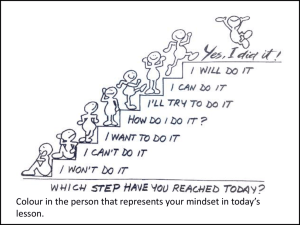

Becoming a Resilient Newcomer Newcomer resilience: Supervisory Influence via Learning and Identification New employees enter organizations full of hope, promise, and desire to be successful – not only adjusting to but contributing within the organization. In short, newcomers desire to adjust quickly while performing effectively (Ashforth, Sluss, & Harrison, 2007). Also, newcomers strive to make a smooth and continuously upward adjustment (cf. Firth, Chen, Kirkman, & Kim, 2014). However, newcomers rarely experience such a positive adjustment trajectory for two major reasons. First, the newcomer process is a form of “identity crisis” in which the newcomer will likely feel a sense of apprehension and stress – all for the simple fact that their work identity is in transition; they are neither “here nor there” (Ellis et al., 2014). Second, scholars have found the socialization process to be quite “lumpy” – with significant ups and downs in both the newcomer’s ability to adjust and capacity to perform (Ashforth et al., 2007). With the heightened uncertainty that comes inherent in the newcomer adjustment process, it is no surprise that newcomers would perceive any failure – no matter how small – as traumatic in terms of either “fitting in” (i.e. adjustment) or “producing” (i.e. performance). Interestingly, these failures may have significant long term impact on the newcomer’s future ability to adjust – especially if the newcomers lack resilience (cf. Sluss & Thompson, 2012). Given the impact of and assumed frequency with which newcomers experience adjustment failures during organizational entry, it is surprising that scholars have not explored how newcomers build resilience while experiencing adjustment difficulties. In this study, we investigate how newcomers build resilience (i.e. the capacity to maintain “positive adjustment in the face of challenging conditions” [Sutcliffe & Vogus, 2003: 95) during initial entry. We particularly focus on how the newcomer’s relationship with their immediate supervisor may create identity-based resources resulting in resilience. Becoming a Resilient Newcomer THEORY Resilience, as a construct, has been investigated quite robustly within both developmental clinical psychology as well as educational psychology. Over time, scholars have moved from exploring the risk and protective factors to focusing on the “protective processes” that build a cadre of internal and external resources allowing the individual to bounce back from a challenging condition or problem in a way that creates learning for responding to future challenges (Luthar & Cicchetti, 2000). Of these “protective processes,” supportive social relationships have been found to provide a significant path to providing a wide range of these internal and external resources (Fletcher & Sakar, 2013). In short, supportive relationships build a relational identity in which learning and adaptation – and, thus, resilience – is encouraged and built (cf. Sluss & Ashforth, 2007). Indeed, newcomer socialization research has found that the newcomer’s relationship with his/her supervisor is key for providing a context for learning and social support resulting in increased adjustment (e.g. Sluss & Thompson, 2012; Sluss, Ployhart, Cobb, & Ashforth, 2012). Following these leads, we argue that supervisors that enact supportive leadership behaviors provide a context that will engender both the newcomer’s ability to see challenging conditions as learning opportunities (i.e. prime a learning goal orientation; VandeWalle, Cron, & Slocum, 2001) as well as provide a basis for which the newcomer to place value on the supervisory relationship such that it becomes self-defining and self-expanding (i.e. relational identification; Sluss & Ashforth, 2007). These two important states – learning goal orientation (i.e. “I can learn from this challenge….”) and relational identification (i.e. “Bouncing back is what I do as part of this relationship”) – provide internal and external identity-based resources important for the newcomer to feel able and capable to respond with resilience. As such, we hypothesize the Becoming a Resilient Newcomer following: H1: The newcomer’s (state-based) newcomer learning goal orientation will partially mediate the association between supportive leadership behaviors (by the newcomer’s supervisor) and the newcomer’s (state-based) resilience. H2: The newcomer’s identification with the supervisory relationship will partially mediate the association between supportive leadership behaviors (by the newcomer’s supervisor) and the newcomer’s (state-based) resilience. METHOD Our study is part of a larger data collection effort among U.S. Navy recruits during “Basic Training.” Our sample will include data from approximately 800 recruits (i.e. 10 divisions with 80 recruits each). We are administering surveys at four time points over the eight week Basic Training period. Basic Training provides a strong context to test how supervisor’s (in our case, the “Recruit Division Commander’s”) leadership behaviors influence the recruit’s resilience. By design, basic training is a stressful, challenging, and traumatic experience for the recruits, making it an ideal context to investigate resilience. In addition, many recruits have left behind “civilian life” such that successfully finishing basic training is important for their identity. Procedure and measures. We measure supportive leadership behaviors (Shamir, Zakay, Brainin, & Popper, 2000), as a level 2 variable during time 1 and time 2 (week one and three). As level 1 variables, we measure learning goal orientation (VandeWalle, et al., 2001) and relational identification (Sluss et al., 2012) during time 3 (week five) while measuring newcomer resilience (state-based measure; Smith, Dalen, Wiggins, Tooley, & Bernard, 2008) during time 4 (week eight). We controlled for both the state-based resilience and the trait-based resilience (Campbell-Sills & Stein, 2007) at time 1. Our initial results from partial data collection demonstrate positive relationships among supportive leadership, learning goal orientation, relational identification, and newcomer resilience. Data collection ends in August 2015. We will then test our hypotheses using multi-level mediation analysis (e.g. Preacher, 2011). Becoming a Resilient Newcomer REFERENCES Ashforth, B. E., Sluss, D. M., & Harrison, S. H. 2007. Socialization in organizational contexts. In G. P. Hodgkinson & J. K. Ford (Eds.), International review of industrial and organizational psychology, vol. 22: 1-70. Chichester, UK: Wiley. Campbell-Sills, L., & Stein, M. B. 2007. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor– Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC): Validation of a 10-Item measure of resilience. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 20: 1019–1028. Ellis, A., Bauer, T. N., Mansfield, L., Erdogan, B., Truxillo, D. M., & Simon, L. S. 2015. Navigating uncharted waters: Newcomer socialization through the lens of stress theory. Journal of Management, 41: 203-235. Firth, B.M, Chen, G., Kirkman, B., & Kim, H. 2014. Newcomers abroad: Expatriate adjustment during early phases of international assignments. Academy of Management Journal, 57: 280-300. Fletcher, D., & Sarkar, M. 2013. Psychological resilience: A review and critique of definitions, concepts, and theory. European Psychologist, 18: 12-23. Luthar, S.S., & Cicchetti, D. 2000. The construct of resilience: Implications for interventions and social policies. Development and Psychopathology, 12: 857-885 Preacher, K.J. 2011. Multilevel SEM strategies for evaluating mediation in three-level data. Mulivariate Behavioral Research, 46: 691-731. Shamir, B., Zakay, E., Brainin, E., & Popper, M. 2000. Leadership and social identification in military units: Direct and indirect relationships. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30, 612-640. Sluss, D. M., & Ashforth, B. E. 2007. Relational identity and identification: Defining ourselves through work relationships. Academy of Management Review, 32: 9-32. Sluss, D.M., Ployhart, R.E., Cobb, M.G., & Ashforth, B.E. 2012. Generalizing newcomer’s relational and collective identifications: Processes and prototypicality. Academy of Management Journal, 55: 949-975. Sluss, D.M., & Thompson, B.S. 2012. Socializing the newcomer: The role of leader-member exchange. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 119: 114-125. Smith, B. W., Dalen, J., Wiggins, K., Tooley, E., Christopher, P., & Bernard J. 2008. The Brief Resilience Scale: Assessing the Ability to Bounce Back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15, 194–200. Sutcliffe, K.M. & Vogus, T.J. 2003. Organizing for Resilience. In Cameron, K., Dutton, J.E., & Quinn, R.E. (Eds.), Positive organizational scholarship. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler. Chapter 7 pp: 94-110. VandeWalle, D., Cron, W.L., & Slocum, J.W. 2001. The role of goal orientation following performance feedback. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86: 629-640.