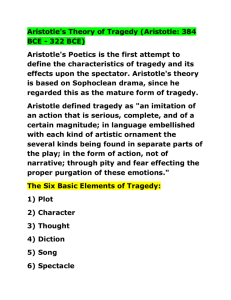

Greek Tragedy: Aristotle's Poetics & Dramatic Forms

advertisement

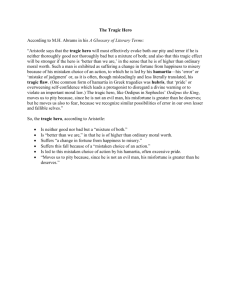

NOTES on Greek Tragedy TYPES of DRAMA The two masks of DRAMA – one with the corners of the mouth turned down and the other with the mouth turned up – are derived from the masks actually worn by actors in ancient Greek plays. These masks represent the two types of drama: TRAGEDY and COMEDY. Tragedy sad unhappy ending typical ending = death Comedy funny happy ending typical ending = marriage Exceptions: o Some comedies make no attempt to be funny. o Successful tragedies, though they involve suffering and sadness, do not leave the spectator depressed. o Some funny plays have sad endings. o A few plays classified as tragedies do not unhappy endings, but conclude with the triumph of the protagonist. The first great theorist of the art of drama was ARISTOTLE (384-322 BC) who wrote about tragedy in his Poetics. Aristotle’s observations about tragedy: o A tragedy is the imitation in dramatic form of an action that is serious and complete, with incidents arousing pity and fear wherewith it effects a catharsis of such emotions. o The language used is pleasurable and appropriate throughout the situation in which it is used. o The chief characters are noble personages (“better than ourselves”) and the actions they perform are noble actions. o The plot involves a change in the protagonist’s fortunes, in which the protagonist usually, but not always, falls from happiness to misery. o The protagonist, though not perfect, is not a bad person. His misfortunes result not from character deficiencies but rather from what Aristotle called hamartia: a criminal act committed in ignorance of some material fact or even for the sake of a greater good. o The tragic plot has organic unity: the events follow not only after one another, but because of one another. o The best tragic plots involve a reversal (a change from one state of things within the play to its opposite) or a discovery (a change from ignorance to knowledge) or both. So, an archetypal TRAGEDY has the following characteristics: 1. The tragic hero is a man of noble stature. He has a greatness about him. He is not an ordinary man, but one of outstanding quality. In Greek or Shakespearean tragedy, he (or she) is usually a prince or a king. This assumes some men to be of “nobler” blood than others by virtue of their aristocratic birth. But we may regard the hero’s kingship as the symbol rather than the cause of the hero’s greatness. That is, he is great, not by virtue of his kingship but by his possession of extraordinary powers, by qualities of passion or aspiration, or by his nobility of mind. The tragic hero’s kingship is also a SYMBOL of his initial good fortune, the mark of his high position. If the hero’s fall is to arouse in us the emotions of pity and fear, it must be a fall from a great height. 2. The tragic hero is good, though not perfect, and his fall results from his committing what Aristotle calls “an act of injustice” (HAMARTIA) either through ignorance or from a conviction that some greater good will be served. Nevertheless, the act is a criminal one and the good hero is still responsible for it, even though he is totally unaware of its criminality and is acting out of the best intentions. His fall is NOT due to a tragic flaw in his character or personality. (This belief is a misunderstanding or misrepresentation of Aristotle’s theory.) Aristotle believed in a just natural order, which does not support a worldview in which personality alone, not one’s actions, can bring on a catastrophe. Thus, because of his actions, the protagonist is personally responsible for his downfall. 3. The hero’s downfall is his own fault, the result of his own free choice – not the result of pure accident or villainy or some overriding malignant fate. Accident, villainy, and fate may contribute to his downfall, but only as cooperating agents; they are not alone responsible. The combination of the hero’s greatness and his responsibility for his own downfall is what entitles us to describe his downfall as tragic rather than as merely pathetic. [If a father of ten children is accidently run over by a bus, the event, strictly speaking, is pathetic, not tragic. When a weak man succumbs to his weakness and comes to a bad end, his end is pathetic, not tragic.] The tragic event involves a fall from greatness brought about, at least partially, by the hero’s free action. 4. The hero’s misfortune is not wholly deserved, for the punishment exceeds the crime. The audience does not come away from a tragedy with the feeling that the hero “got what was coming to him” but rather with the sad sense of the waste of human potential. What impresses one most about the tragic hero is not his weakness, but his greatness. He is larger than life, or as Aristotle says, “better than ourselves.” He reveals to us the dimensions of human possibility and his fall fills us with pity and fear. 5. The fall of the hero is not pure loss. Though it may result in the protagonist’s death, it involves, before his death, some increase in awareness, some gain in self-knowledge – some “discovery” (as Aristotle puts it) – some change from ignorance to knowledge. This discovery may be learning the truth about some fact or situation of which the protagonist was ignorant, but this discovery is accompanied or followed by an significant insight on the part of the hero – a fuller self-knowledge – an increase not only in knowledge, but in wisdom. Often this increase in wisdom involves some sort of reconciliation with the universe or with the protagonist’s situation. The hero exits, not cursing his fate, but accepting it and acknowledging that his fate is, to some degree, just. 6. Though tragedy involves solemn emotions – pity and fear (think compassion and awe) – it does not, when well performed, leave its audience in a state of depression. Some catharsis, or some sort of emotional release at the end of the play is a common experience of those who witness great tragedies on the stage. This emotional release may be a feeling of exhilaration brought on by a fresh recognition of human greatness and nobility, a sense that human life has unrealized potentialities. Though the hero may be defeated, he at least has dared greatly and he gains understanding from his defeat. Comedy: According to critic Northrup Frye, “Comedy lies between satire and romance.” There are two chief kinds of comedy: 1) scornful (or laughing) comedy and 2) romantic (or smiling) comedy. Of the two, scornful or satirical comedy is the older and probably the still more dominant of the two. Tragedy versus Comedy: Tragedy… Comedy… Emphasizes human greatness Emphasizes human weakness Celebrates human freedom Points up human limitations Emphasizes hero’s uniqueness Emphasizes the protagonist’s commonness Emphasizes the individual Emphasizes types of individuals (Oedipus Rex, Hamlet, etc) (The Miser, The Double Dealer) Hero judged by moral standards Protagonist judged by social standards How far does hero soar above society? How well does protagonist conform to society and adjust to suit the expectations of the group? Unity of plot (logical cause & effect) Implausible plots, disguises, mistaken identities Ending of life = death Forget death; choose marriage (new beginnings) COMEDY: Wherever human beings fail to measure up to their own resolutions or to their own self-conceptions, wherever they are guilty of hypocrisy, vanity, or folly, wherever they fly in the face of good sense and rational behavior, comedy exhibits their absurdity and invites the audience to laugh at them. Hamlet: “What a piece of work is a man! – how noble in reason! – how infinite in faculty! – in form and moving how express and admirable! – in action how like an angel! – in apprehension how like a god!” (TRAGIC OUTLOOK) Puck: “Lord, what fools these mortals be!” (COMEDIC OUTLOOK) Satirical Comedy: o Exposes and is an antidote to human folly o Its function is partly critical and partly corrective o It reveals to its audience a spectacle of human ridiculousness that it makes the audience want to avoid. o We laugh out loud at the primary characters. o Comedy can be educative as well as being enjoyable. Romantic Comedy: o Emphasizes sympathetic rather than ridiculous characters: often young lovers o These characters are put in difficult situations from which they are rescued in the end. o Fortunes are restored in the end. o These characters are not lofty or commanding; rather they are sensible and good, not noble, aspiring, and grand (as in tragedy) o They do not strike us with awe. o They do not so challengingly test the limits of human possibilities o They move in a smaller world o o The romantic comedy usually has a number of lesser characters whose folly is held up to ridicule (just as a satirical comedy may have a pair of young lovers who are sympathetic and likable) We laugh out loud at the secondary characters (see satirical comedy) TWO OTHER IMPORTANT DRAMATIC FORMS: MELODRAMA: o o o o o o o o o Like tragedy, attempts to arouse feelings of fear and pity, but does so through cruder means Conflict oversimplified between good and evil depicted in absolute terms Plot is emphasized at the expense of characterization. Plot driven by sensational incidents Good finally triumphs over evil, so the ending is happy The hero marries the heroine; villainy is foiled or crushed Moral issues are oversimplified Avoids complex insights into the human condition Escapist rather than interpretive FARCE: o o o o o o o o Aimed at arousing explosive laughter through crude means Conflicts are violent and usually at the physical level Plot is emphasized at the expense of characterization Improbable situations and coincidences are emphasized at the expense of articulated plot Comic implausibility is raised to the level of absurd impossibility Coarse wit, practical jokes, and physical actions are staples (including tripping over benches, brawling, knocking people down, etc.) Psychologically, farce may purge the audience of hostility and aggression. Escapist rather than interpretive. Greek Drama: o o o Plots of Greek tragedies based on legends the Greek audience was familiar with The audience already knows something about the characters and their fates, so the playwright could make powerful use of DRAMATIC IRONY and ALLUSION Much of the audience’s delight is seeing the playwright work out the details of the story