Perspectives

advertisement

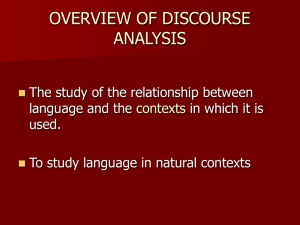

北京师范大学 教育研究方法讲座系列 (2): 教育政策研究 第二讲 教育政策研究的知识论基础:理论视域的探讨 A. Perspectives in Policy Studies in Education: An Overview 1. Analytical-technical perspective a. Epistemological premise: Public policies are social facts. They are social actions, programs and projects undertaken by the modern state to intervene the state of affairs of particular public domains in a modern society. b. Aims of enquiry: Accordingly, policy studies is scientific enquiry aims to provide causal explanation for the question why the state undertaking particular policy actions and not the otherwise. More specifically, it aims to analytically identify and verify the antecedent conditions that caused the policy action to take place. c. Practical premise: Based on the causal relation verified by policy studies, policy makers can then make prediction, means-ends calculation, and technical engineering about the policy situation concerned. It aims to impose technical control over the situation. 2. Interpretive-political perspective: a. Epistemological premise: Public policies are social construction of realities. They are meanings, values, preferences and desires attributed by the modern state and others interest groups to the state of affairs of particular public domains in a modern society. b. Aim of enquiry: Accordingly, policy studies is social enquiry aims to interpret and explain why particular meanings and values are signified in a policy “text” in a policy context, and not the otherwise. c. Practical premise: Based on the interpretations and understandings revealed by policy studies, policy participants can then engage in communication and dialogue which aim to facilitate mutual understanding, to nurture consensus, and plausibly to work out politically reciprocal solution to the policy issue in point. 3. Discursive-critical perspective: a. Epistemological premise: Public policies are authoritative values and even “effective discursive totality” legitimized and imposed by the modern state on the state of affairs in a particular public domain in a modern society. b. Aim of enquiry: Accordingly, policy studies is critical enquiry aims to reveal how and why particular policy discourses are legitimized in a policy arena. c. Practical premise: Based on the critical studies on policy discourse, policy critics can then reveal and assess the possible systemic biases and distortions hypostatized and legitimatized in particular policy domain and to strive to liberate human and social potentials from these biases and distortions. W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 1 (I) The Analytic-Technical Perspective in Policy Studies A. The Epistemological Basis: Analytical Positivism 1. Stuart Nagel’s conception of policy analysis model a. “Public Policy analysis can be defined as determining which of various alternative public or governmental policy will most achieve a given set of goals in light of the relations between the policies and the goals. That definition brings out four key elements of policy evaluation which are: i. Goals, including normative constraints and relative weights for the goals. ii. Policies, programs, projects, decisions, options, means, or other alternatives that are available for achieving the goals. iii. Relations between the policies and the goals, including relations that are established by intuition, authority, statistics, observation, deduction, guesses, or other means iv. Draw a conclusion as to which policy or combination of policies is best to adopt in light of the goals, policies, and relations.” (1986, p. 247) b. Stokey and Zeckhauser’s Framework for policy analysis i. Establishing the Context. What is the underlying problem that must be dealt with? What specific objectives are to be pursued in confronting this problem? ii. Laying out the alternatives. What are the alternative courses of action? What are the possibilities for gathering further information? iii. Predicting the consequences. What are the consequences of each of the alternative actions? What techniques are relevant for predicting these consequences? Of outcomes are uncertain, what is the estimated likelihood of each? iv. Valuing the outcomes. By what criteria should we measure success in pursuing each objective? Recognizing that inevitably some alternatives will be superior with respect to certain objectives and inferior with respect to others, how should different combinations of valued objectives be compared with one another? v. Making a choice. Drawing all aspects of the analysis together, what is the preferred course of action? c. In searching of causality, prediction, and prescription for policy action and logical positivism emerged from natural science seemingly pointing the way. And three basic premises of logical logical positivism i. Methodological monism ii. Logical empiricism as the ideal-typical method of verification iii. Deductive-Nomological model as the idea-typical model of explanation 2. Deductive-Nomological (D-N) explanation: The ideal-typical model of causal explanation in logical positivism: W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 2 The D-N explanation is the type of explanation commonly used in researches in natural sciences. It makes up of three parts: a. The explanatory premises or the casual law (covering law), which is a universal statement of the sufficient and necessary conditions (explanans/cause) for the truth of the explanandum (effect). Accordingly, a causal law in natural science must comprises the following components i. The factual truth of both the the explanandum (i.e. the phenonmenon to be explained) and the explanans. ii. The conditionality between the explanandum and explanans - Sufficient conditions: It refers to the kinds of conditionality between the explanandum and explanans, in which the explanans can exhaustively but not universally explain the truth of the explanandum. - Necessary conditions: It refers to the kinds of conditionality between the explanandum and explanans, in which the explanans can universally but not exhaustively explain the truth of the explanandum. - Sufficient and necessary conditions: It refers to the kinds of conditionality between the explanandum and explanans, in which the explanans can both exhaustively and universally explain the truth of the explanandum. iii. The temporal order of the explanans must be in precedence to the explanandum b. The initial condition, which defines the property of a specific case of the explanandum. c. The conclusion, which state the exhaustive explanation of the specific explicandum by the explanans. 3. The compromised model: Statistical-Probabilistic (S-P) explanation: The S-P model is the type of explanation commonly use in quantitative researches in social sciences. It is also made up of three parts similar to those in nomological-deductive explanation. There are two differences in probabilistic explanation. One is that the explanatory premises is not in the form of law-like / nomological statement of the sufficient and necessary conditions of the truth of the explanandum but only a probabilistic statement specifying the likelihood of the causal relationship between the explanans and explanandum. The second difference is that in the conclusion, the specific explanandum under study cannot be exhaustive explained by the explanans but can only be explained in probabilistic terms. 4. Logical-empiricism: The exemplary method of verification in logical-positivism a. By empiricism, it refers to the method of verification based primary by sensory experiences of human being. More specifically, it is based on recorded experiences methodically collected by scientists. More importantly, these recorded experiences will then be set against their respective propositions to see whether they correspond each other. And it is through this operation of so call correspondence principle that scientific propositions will be verified against the external national world. W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 3 b. Apart from empirical verification that rely on human experiences, scientists can also rely on pure logical inference and mathematical calculations to verify their propositions. For example propositions in in geometry and mathematical physical are usually not verified with empirical data but pure mathematical and logical inferences. B. The Ontological Basis: Technical Rationalism 1. The concept of instrumental and technical rationality a. The concept of rationality: Rationality can be defined as conscious and knowledgeable ways human beings approaches and even masters the world around them. Rationality therefore is a state of mind and a way of life, in which human beings strive to master their physical and even their social environments. b. The concepts of instrumental and substantive rationality i. Instrumental rationality refers to conscious and knowledgeable process through which human beings calculate and choose the most expedient means to achieve preconceived and/or predetermined end. ii. Substantive rationality refers to conscious and knowledgeable process through which human beings decide the ends most worthy of achieving. c. The instrumental-technical turns in policy studies i. Policy scientists who adhere to value-neutral or even value-free method of inquiry advocate that substantive choice of policy end are political decisions and should be left to politicians. ii. Accordingly, they contend that policy scientists should confine themselves to the technical issues of choosing the best, or more specifically the most cost-effective policy instruments or means to attain the “politically” pre-determined ends. 2. Technical-rational perspective in policy studies a. Following the conclusions drawn from analytic-positivist policy studies, the next task to be performed by policy analysts is to work out, if possible to the last technical details, the action plan to carry out the policy measures. Hence, it is a task guarded by instrument and technical rationality. b. Assumptions of comprehensive (technical) rational model in policy studies: (Forester, 1989, Pp. 49-54) i. The agent/actor: A single decision-maker (or a group of fully consenting decision makers) who is a utility-maximizing, instrumentally rational actor ii. The setting: Analogous to the decision-maker’s office, “by assumption a closed system” iii. The problem: Well defined problem, “its scope, time horizon, value dimensions, and chains of consequences are clearly given” and close at hand. iv. Information: Assumed to be “perfect, complete, accessible, and comprehensible.” v. Outcome: A single best solution or the most optimum resolution C. Criticisms and Revisions 1. Herbert Simon’s concept of bounded rationality W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 4 a. Simon’s defines that “rationality denotes a style of behavior (A) that is appropriate to the achievement of a given goals, (B) within the limits imposed by given conditions and constraints.” Simon, 1982, p.405) b. The concept of satisfice: Simon differentiates two stances in regard to (A), i.e. the degree of “appropriateness to goal achievement. i. Maximizing or optimizing stance of the “economic man”: “While economic man maximizes - selects the best alternative from among all those available to him” ii. Satisificing stance of the “administrative man”: “Administrative man satifices - look for a course of action that is satisfactory or ‘good enough’. (Simon, 1957, p. xxv) c. The concept of bounded rationality: In regard to (B), Simon indicates that “It is impossible for the behaviour of a single, isolated individual to rearch any high degree of rationality. The number of alternatives he must explore is so great, the information he would need to evaluate them so vast that even an approximation to objective rationality is hard to conceive. Individual choice takes place in an environment of ‘givens’ – premises that are accepted by the subject as base for his choice; and behaviour is adaptive only within the limits set by these ‘givens’.” (Simon, 1957, p. 79; my emphasis) Simon specifies limitations imposed by the environment of givens are i. Limitation of the knowledge - Incomplete and fragmented nature of knowledge, - Limits of knowledge about the consequences, i.e. predictability of knowledge ii. Limitations of the cognitive ability of the decider makers - Limits of attention - Limits on the storage capacity of human mind - Limits of the learning ability of human beings, i.e. observation, communication, comprehension, …. - Limits on changes of status quo, i.e. human habits, routine, mind set, … - limits on organizational environments. 2. Dahl and Lindblom’s conception of rational calculation a. Limitations and difficulties in means-end rational calculation i. Information deficiency: Relevant or even essential information to the means-end rational calculation may be incomplete, unavailable, difficult to obtain, … ii. Communication problem: Available information may not be able to be dissimulated to all decision-making parties or the information may appear to be difficult to comprehend. iii. The number of variables involved is too many to be exhausted. vi. The complexity of the relations among variables is too complicated to be comprehended not to mention exhausted. b. Scientists’ solutions to cognitive deficiency in means-end rational calculation “Scientists deal with the problem of information by systematic observation, with the problem of communication by developing a W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 5 precise and logical language usually including the language of mathematics; with the problems of an excessive number of and complex relations among variables by specialization, controlled by experiment, quantification, rigorous and system analysis, and exclusion of phenomena not amenable to these methods.” (Dahl & Lindblom, 1992, p. 78) In summary, these methods include i. Codification: Method of reducing and unifying numerous, complicated and disorderly information into comprehensible units ii. Quantification: Method of quantifying information and units into comparable values. iii. Sampling: Selectively analyzing a fragment, a specimen of the phenomenon under observation. vi. Observations in control situations or by randomization. v. Modeling: Model “is a purposeful reduction of a mass of information to a manageable size and shape, and hence is a principal tool in the analyst’s work-tool. Indeed, we will be employing models throughout this book.” (Stokey & Zeckhauser, 1978, p.9) 3. Choices under calculated risk a. Risk can be construed as “the residual variance in a theory of rational choice” (March, 1994, p. 35) or more specifically, the unexplained variance in a causal modeling equation. It is basically grown out of the epistemological constraints of the scientific means-end rational model. b. Therefore, “calculated risks are often necessary because scientific methods have not yet produced tested knowledge about the probable consequences of large incremental changes…and existing reality is highly undesirable.” (Dahl & Lindblom, 1992, p. 85) c. Growing industry for risk estimation and risk management in public policy 4. Charles Lindblom’s science of muddling through Charles Lindblom agrees with Simon on the limitations of human rationality, yet Lindblom diagnoses that the sources of these limitations are more than the cognitive capacity of human mind. He suggests that limitations are integral parts of the very process of policy making. Lindblom characterizes this process as “successive limited comparison” and “muddling through”. a. “Incrementalism is a method of social action that takes existing reality as one alternative and compares the probable gains and loses of closely related alternatives by making relatively small adjustments in existing reality, or making larger adjustments about whose consequences approximately as much is known as about the consequences of existing reality, or both.” (Dahl & Lindblom, p. 82) W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 6 b. Lindblom’s two models of decision-making Rational comprehensive Successive limited comparison 1a Clarification of values or objectives distinct from and usually prerequisite to empirical analysis of alternative policies 1b Selection of values, goals and empirical analysis of the needed action are not distinct from one another but are closely intertwined 2a Policy formulation is therefore approached through means-ends analysis: first the ends are isolated; then the means to achieve them are sought 2b Since means and ends are not distinct, means-ends analysis is often inappropriate or limited 3a The test of a ‘good’ policy is nthat 3c it can be shown to be the most appropriate means to desired ends The test of a ‘good’ policy is typically that various analysts find themselves directly agreeing on a policy (without their agreeing that it is the most appropriate means to an agreed objective) 4a Analysis is comprehensive; every 4b important relevant factors is taken into account Analysis is drastically limited: a. important possible outcome are neglected; b. important alternative potential policy are neglected; c. important affected values are neglected 5a Theory is often heavily relied upon A succession of comparisons greatly reduces or eliminates reliance on theory 5b 5. John Forester’s typology of bounded rationality (see Table 4) a. Bounded rationality I: Cognitive limits b. Bounded rationality II: Social differentiation c. Bounded rationality III: Pluralist conflict d. Bounded rationality IV: Structural distortions W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 7 W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 8 D. A Case Study HKSAR 1. Analytic-positivist perspective in education policy a. Codification i. The case of MOI: MIG, EMI-capables, EMI-schools, ii. The case of HKSAR education reform: Quality schools, quality teachers, quality school management, quality indicators b. Quantification: i. The case of MOI: - MIGAI, II, and III, - EMI-capables: the top 40% in pre-S1 HKAT, - EMI-schools = on a 3-year average, 85% of S1 intakes being EMI-capables ii. The case of HKSAR education reform - Performance Indicators for HK Schools, which are analytically divided into 4 domains, 14 areas, 28 components, 186 performance evidences each of which is in turn measures a 4-point scale - 23 Key Performance Measures, - Value-added index of SVAIS, - Basic Competence Assessment - The teacher Competencies Framework , which are analytically divided into 4 domains, 16 areas, and 46 indicators; which are in turn are measured by 5-point scales and ranked into 3 levels. - 5-level Language Proficiency (Benchmark) Assessment for teachers c. Sampling and randomization: Sampled schools and their attributes found in policy studies can be applied to other non-sampled schools in the assumption that factors other than those controlled by policy measures can be randomized. i. The case of MOI policy: - Classification of MIG-I, -II & -III or EMI-capable students - Classification of EMI and CMI schools ii. The case of HKSAR education reform - Classification of quality schools - Classification of professionally competent and/or linguistic proficient teachers - Classification of students and schools passed the Basic Competence Assessment d. Modeling: i. Monolingual model of mother-tongue instruction vs. triglossiic model ii. Input-output model: Value-added model, linear regression model, ordinary-least-square model, multi-level regression model, … iii. Educational process model: Quality school model, Quality-Assurance Inspection, School-Self Inspection model, External School Review… iv. Model of professional teachers: Analytically fragmented and technocratic professional vs. heuristic learned-professional 2. Technical-rational perspective in education policy a. Technocratic procedures of assessments and evaluation W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 9 i. Procedures and criteria of the application for EMI schools ii. Procedures and criteria of TSA, pre-S1 HKAT, value-added index ii. Procedures of QAI, SSE, and ESR in Quality Assurance Mechanism iii. Procedures of benchmark and/or competence assessments of teachers b. Technocratic divisions of constituents in education system i. EMI and CMI divisions ii. Quality divisions/ stratifications for schools, teachers & students c. Differentiated educational treatments (positive or negative) i. Ascending and descending mechanism in MOI policy ii. Outstanding Teachers and Schools Awards iii. Schools to be shut down (II) Interpretive-Political Perspectives in Policy Studies A. Interpretive Perspective in Policy Studies: From of Fact to Meanings 1. David Easton defines public policy as “the authoritative allocation of values for the whole society.” (Easton, 1953, p. 129) 2. Stephen Ball indicates that “Policy is clearly a matter of the ‘authoritative allocation of values’; policies are the operational statements of values, ‘statements of prescriptive intent’ (Kogan 1975 p.55). But values do not float free of their social context. We need to ask whose values are validated in policy, and whose are not. Thus, The authoritative allocation of values draws our attention to the centrality of power and control in the concept of policy’ (Prunty 1985 p.135). Policies project images of an ideal society (education policies project definitions of what counts as education).”(Ball, 1990, p. 3) In another occasion, Ball specifies his own approach to policy study that “in current writing on policy issue I actually inhabit two very different conceptualization of policy. …I will call these policy as text and policy as discourse. …The point I am moving to is that policy is not one or the other, but both: they are ‘implicit in each other’.” (1994, p.15) 3. Dvora Yanow defines “public policy as texts that are interpreted as they are enacted by implementers, (and)…as texts that are ‘read’ by various stakeholder groups.” (2000, p. 17) Therefore, an interpretive approach to policy analysis …is one that focuses on revealing the meanings, values, and beliefs expressed and signified in a given policy text, and to analysis the process by which these meanings are communicated to and ‘read’ by various audiences. 4. Basic assumptions of interpretive approach to public policy studies: a. Public policy is not construed as self-defined phenomenon and/or natural phenomenon treated in natural science, but is taken as human artifact deliberated and constructed by human beings with specific intents and particular meanings. Accordingly, policy studies are research efforts to identified the meanings and values allocated, imputed, and attributed to a particular policy phenomenon by all parties concerned. W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 10 b. Since the primary meaning-constructor (or more appropriately put ‘author’) of public policy is the modern state. As by definition the modern state is the sovereign power and authority over a definitive territory and its residents, hence public policy studies are research efforts to investigate what are the intents, meanings or values that the state has ascribed to a particular public policies and why. c. Furthermore, in pluralistic and democratic political system, the author of public policy is not confined to the sovereign state. Various interested parties may also attribute different or even contradictory meanings to a same policy phenomenon and take different or even antagonistic stances towards a policy prescription. c. Accordingly, public policy study is research efforts striving i. to explore what and how meanings and values are written / encoded into policy “texts” by the state or the government. ii. to explore what and how meanings and values are read / decoded from public policy “texts” by interest groups / interpretive communities, i.e. hermeneutic and ethnographic studies of interpretations of public policy by social groups. iii. to explore what authoritative meanings and values are emerged and constituted amid these diverse interpretations of public policy. iv. to expose the politicking processes via which authoritative meanings and values are constructed within the political context of a public policy. B. Intentional explanation: Explaining the State’s Acts 1. Georg H. von Wright’s Two Traditions of Inquiry a. “It is therefore misleading to say that understanding versus explanation marks the difference between two types of scientific intelligibility. But one could say that the intentional or nonintentional character of their objects marks the difference between two types of understanding and of explanation.” (von Wright, 1971, p.135) b. Distinction between causal and teleological explanations i. Causal explanation: It refers to the mode of explanation, which attempt to seek the sufficient and/or necessary conditions (i.e. explanans) which antecede the phenomenon to be explained (i.e. explanandum). Causal explanations normally point to the past. ‘This happened, because that had occued’ is the typical form in language.” (von Wright, 1971, p. 83) It seeks to verify the antecedental conditions for an observed natural phenomenon. This mode of explanation can further be differentiated into - Deductive-nomological explanation - Inductive-probabilistic explanation ii. Teleological explanation: It refers to the mode of explanation, which attempt to reveal the goals and/or intentions, which generate or motivate the explanadum (usually an action to be explained) to take place. “Teleological explanations point to the future. ‘This happened in order that that should occur.’” (von Wright, 1971, p. 83) This mode of explanation can be differentiated into W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 11 - Intentional explanation - Rational-choice explanation - Functional explanation (Quasi-teleological explanation) 2. Re-orientating the mode of explanation in policy studies: a. Intentional explanation has been advocated by some social scientists as the typical mode of explanation used in social sciences. In fact, as Jon Elster underlines, its feature "distinguishes the social sciences from the natural sciences." (Elster, 1983, p. 69) b. However, to inquire into the intentions and subjective meanings of actors and groups of actors in public policy, for examples statesmen, politicians, frontline policy service deliverers, policy service recipients, political parties, interest groups, etc. Policy researchers encounter one of the central methodological problems in social science. This aporia has be aptly depicted by Max Weber as follow: "Sociology is a science concerning itself with the interpretive understanding of social action and thereby with causal explanation of its course and consequence." (Weber, 1978, p.4) C. Policy Studies as Intentional Explanation of the State’s Actions (1): Interpretative Approach 1. What is meaning? a phenomenological tion a. Alfred Schutz, one of the prominent phenomenological sociologists of the twentieth century suggests in his book The Phenomenology of Social World has offered a solution to Weber’s Aporia in interpretative social science and more specifically interpretive policy studies as follows b“Meaning is a certain way of directing one’s gaze at an item of one’s experience. This item is thus ‘selected out’ and rendered discrete by a reflexive Act. Meaning indicates, therefore, a peculiar attitude on the part of Ego toward the flow of its own duration.” (Schutz, 1967, p. 42) c. This definition may be discerned with the three constituent concepts in phenomenology, namely, attention, intention and protention. In other words, meanings are made up of the attention, intention and protention that the Ego has attribute to an object in the concrete and discrete world. i. Attention refers the act of one’ consciousness in “selecting out” an object from the concrete and discrete world ii. Intention refers the act of one’s consciousness in forming a perception and attitude towards the object and retaining it and recalling it in the future iii. Protention refers to the act of consciousness of formulating an action plan (a project) to fulfill one anticipation towards the object 2. Schutz’s concept of action By applying the conceptual apparatus derived from phenomenological philosophy, Schutz proposes to clarify Max Weber’s conception of subjective meaning of social action in interpretive sociology in the following way. “Now we are in a position to state that what distinguishes action from behavior is that action is the execution of a projected act. And we can W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 12 immediately proceed to our next step: the meaning of any action is its corresponding projected act. In saying this we are giving clarity to Max Weber’s vague concept of the ‘orientation of an action’. An action, we submit, is oriented toward its corresponding projected act.” (Schutz, 1967, p. 61) 3. Schutz’s concept of meaning-context a. By applying the constituent concepts of phenomenology, Schutz further suggests that meanings forged within one’s Ego are “configurated” into a whole, which Schutz called “meaning-context”. By meaning-context, Schutz characterized it as follows “Let us define meaning-context formally: We say that our lived experience E1, E2, …, En, stand in a meaning-context if and only if, once they have been lived through in separate steps, they are then constituted into a synthesis of a high order, becoming thereby unified objects of monothetic attention.” (Schutz, 1967, p.75) b. Schutz indicates that meaning-context derived within one’s inner time consciousness bears numbers of structural features. (Schutz, 1967, p. 74-78) i. Unity: Though intentional acts and/or fulfillment-act various meaning-endowing experiences are unified and integrated into coherent whole within the Ego. Hence, meaning-context generated from meaning-endowing experiences also bears the internal structure of unity and coherence. ii. Continuity: As lived experiences are set within the stream of consciousness of duration (i.e. Durée), therefore, the meaning-context thereby derived is internally structured into a continuity of temporal ordering. iii. Hierarchy: Through her lived experiences in different spheres of the life-world, individual will congifurated various meaning-contexts for lived experiences in various spheres of life. And these complex meaning-contexts are structured in hierarchical order according to their degree of meaningfulness and significance. 4. Accordingly, interpretive policy studies can be construed as research efforts to investigate a. what are the attention, intention and protention that the state granted to a policy phenomenon and/or issue; b. what are the attention, intention and protention that interested parties within a policy arena attributed to the policy text produced by the state; c. how these attentions, intentions and protentions are related to the meaning-context of the state and to those of the interested parties; and why. D. Policy Studies Intentional Explanation of the State’s Actions (2): Hermeneutic Approach 1. Hermeneutic study of public policy ‘Hermeneutics is a discipline that has been primarily concerned with the elucidation of rules for the interpretation of texts.” (Thompson, 1981, p.36) W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 13 2. What is interpretation? a. “Interpretation … is an attempt to make clear, to make sense of an object of study. This object must, therefore, be a text, or a text-analogue, which in some way is confused, incomplete, cloudy, seemingly contradictory in one way or another unclear. The interpretation aims to bring to light an underlying coherence or sense. …The object of a science of interpretation must thus have (a) sense (coherence and meaning) , distinguishable from its (b) expression, which is for or by (c) a subject.” (Taylor, 1994, p.181-182) b. “When we speak of the ‘meaning’ of a given predicament, we are using a concept which has the following articulation: i. Meaning is for a subject… ii. Meaning is of something… iii. Things only have meaning in a field, that is, in relation to the meanings of other things.” (Taylor, 1994, p. 185-186) c. Dimension of linguistic meaning: “Meanings …. is for a subject, of something, in a field. This distinguishes it from linguistic meaning which has a four- and not three-dimensional structure. Linguistic meaning is for subjects and in a field, but it is the meaning of signifiers and it is about a world of referent.” (Taylor, 1994, p.186) i. Meaning for a subject ii. Meaning in a field iii. Meaning of something - Meaning of the signifier - Meaning about a world of referent 3. What is a Text? (Ricoeur, 1981, p. 145-164) a. "A Text is any discourse fixed by writing" (p.145) i.e. a fixation of speech act by writing. i. Fixation enables the speech to be conserved, i.e. durability of text ii. A text ‘divides the act of writing and the act of reading into two sides, between which there is no communication. … The text thus produces a double eclipse of the reader and the writer.’ (p. 146-47) iii. Policy text can therefore be primarily conceived as the authoritative fixation of meanings by the government b. Hermeneutical Function of Distanciation (Ricoeur, 1981, p. 131-44) i. Text as language event and speech act - Distanciation between language event and meaning - Articulation of meaning in language event is ‘the core of the whole hermeneutic problem.’ (p. 134) ii. Text as work - Distanciation between text as the work and its authors - ‘Hermeneutics remains the art of discerning the discourse in the work; but this discourse is only given in and through the structures of the work. Thus interpretation is the reply to the fundamental distanciation constituted by the objectification of man in work of discourse, an objectification comparable to that expressed in the products of his labour and his art.’ (P. 138) W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 14 iii. Distanciation between act of writing and act of reading ‘The text must be able to…”decontextualizse” itself in such a way that it can be “recontextualise” in a new situation – as accomplished…by the act of reading.’ (p. 139) vi. Distanciation between the text and the reference and denotation of discourse - The world the text: ‘Reference…distinguishes discourse from language, the latter has no relation with reality, its words returning to other words in the endless circle of the dictionary. Only discourse, we shall say, intends things, applies itself to reality, expresses the world.’ (p. 140) - ‘The most fundamental hermeneutical problem … is to explicate the type of being-in-the world (life-world) unfolded in front of the text’. (p.141) v. Four hermeneutic problems in policy-text study - Hermeneutic problem of bridging the distanciation between policy texts and policy meanings, values and measures - Hermeneutic problem of bridging the distanciation between policy texts and authors’ (governmental) intents - Hermeneutic problem of bridging the distanciation between policy texts and readers ‘reading of the texts - Hermeneutic problem of bridging between the distanciation between the policy texts and their referencing world 4. From texts to textuality and intertextuality a. The concept of textuality: Apart from retrieve the meanings embedded in texts, hermeneutic study can also explore another dimension of texts, i.e. “the texture of texts, their form and organization” (Fairclough, 1995, p. 4). By introducing the concept of textuality into hermeneutic study, text analysis can then go beyond studying texts in linguistic forms (written or spoken) and explore texts, which take on multi-semiotic forms. b. The concept of multi-semiotic textuality is especially significant in the age of mass communication and then the information age i. In the mass-communication age, television, the exemplar text of multi-semiotic form is television. ii. In the information age, literal texts have been further replace by digital-imagery texts through computer-mediated-communication and in the internet. c. Dimensions of textuality of the policy text: i. Genre ii. Frame iii. Rhetoric iv. Narrative (To be discussed on Lecture 6: Policy Making Process) c. As the concept of texuality is applied to policy studies in the information age, it becomes apparent that analysis of policy text should extend beyond the analysis of the policy documents in its literal form and to analyze meanings and values embedded in policy texts in multi-semiotic forms, such as documentaries, commercials, and news footages in TV; and websites in Internet. W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 15 d. The concept of intertextuality: It refers to the texture of the text when it is set against its social and history contexts. In other words, “intertextuality implies ‘the insertion of history into the text and of this text into history’. (Kristeva, 1986, p. 39) By ‘the insertion of history into the text’, …text absorbs and is built out of texts from the past.” (Fairclough, 1992, p.102) e. As the concept of intertextuality is applied to policy studies, it implies that policy documents should be analyzed in conjunction synchronically with other current policy texts and/or diachronically with policy texts in the past. 5. Multi-lateral hermeneutic study of public policy The multi-lateral process of writing (encoding) and reading (decoding) of policy texts (Ball, 1992) a. Multiple authors in the production processes of policy texts b. Multiple readers in the processes formulation and implementation of policy texts c. Notions writerly and readerly texts: i. The writerliness of policy texts refers to the flexibility built in policy texts which “invite the reader to ‘join-in’, to ‘co-operate’ and co-author’. (p. 11) In other words, it provides readers rooms to interpret or even re-write the policy texts. ii. The readerliness of policy text refers to the rigidity built in policy texts which provide “minimum of opportunity for creative interpretation by the reader(s).” (p.11) d. Reciprocating, bargaining and interacting relationship between writers and readers of policy texts 6. Conception of interpretive communities in policy study (Yanow, 2000) a. Given the multi-lateral features in policy interpretations, policy arguments are therefore involved multiple communities, each of which can have their own interpretations of the policy text and subsequently produce their own texts (in multi-semiotic forms) in relation to the policy argument. b. Hence, the starting point of interpretive inquiry into a particular policy issue is to identify the various interpretive communities participate in the formulation and implementation processes of the policy. c. The second step access the “local knowledge”, i.e. the definition of situation, knowledge at hand and system of relevance, produced by different interpretive communities. The access can be attained by means of document analysis, conversational interviews and participation observations with different interpretive communities d. By juxtaposing and mapping out the similarities and differences in the local knowledge produced by various interpretive communities with regard to the policy in point, the architecture of arguments constituted around the policy issue in point can be revealed. E. Policy Studies as Rational-Choice Explanation of the State’s Actions 1. Apart from the phenomenological perspective, another perspectives, namely ration-choice theory, has also formulate an approach to intentional explanation with its conceptual apparatus. 2. Assumptions of rational-choice theory in intentional explanation: Jon W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 16 Elster underlines that in order to avoid the idiosyncratic and subjective nature of intentional explanation under phenomenological perspective, we can assume that the actors in point, i.e. the state, are agents who are endowed with rationality and autonomy; and their undertakings are conscious and rational actions. 3. Intentional explanation: In light of these two assumptions, Elster has reformulated intentional explanation by analytically decompose it into "a triadic relation between action, desire and belief." (Elster, 1983, 90) “A successful intentional explanation establishes the behavior as action and the performer as an agent. An explanation of this form amounts to demonstrating three place relation between the behavior/action (A), a set of cognitions (C) entertained by the individual and a set of desire (D) that can also be impute to him. (Eslter, 1994, P. 311) Cognition Action Desire Given this basic schema, Elster formulated intentional explanation with the following three propositions: (1) Given C, A is the best means to realize D (2) C and D cause B (3) C and D cause B qua reasons 3. Rational-choice explanation: Accordingly, Elster asserts further that “rational-choice explanation goes beyond intentionality in several respects.” (Elster, 1994, P.313) The basic requirement is that the triadic schema must be consistent both internally and externally. a. Internal consistency: In order to turn a subjective intentionality into a rational project of action, Elster suggests that it must comply with two propositions (4) The set of beliefs C is internally consistent (5) The set of desires D is internally consistent b. External consistency: Elster further asserts that “one might want to demand more rationality of the beliefs and desires than mere consistency. In particular, one might require that the beliefs be in some sense substantively well grounded, i.e. inductively justified by the available.” (Elster, 1994, P.314) As a result, there are three more conditions to be complied with: (1b) The belief must be the best belief, given the available evidence (2b) The belief must be caused by the available evidence (3b) The evidence must cause the belief ‘in the right way’ Accordingly, the triadic schema may then be reformulated as follow W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 17 Evidence Cognition Action Desire Source: Elster, 1994, P. 318 4. More recently Elster has further reformulated the model of rational-choice explanation as follows Information Beliefs Action Desire Source: Elster, 2009, P. 15 F. Policy Studies as Quasi-Teleological Explanation of the State’s Actions: Functional Explanation of Institutional Persistence 1. This type of explanation is most commonly used in biology. It "takes the form of indicating one or more functions (or even dysfunctions) that a unit performs in maintaining or realizing certain traits of the system to which the unit belongs." (Nagel, 1979, p. 23) For example, in explaining why human being has lung, the typical explanation in biology is that lung (L) performs the function of breathing (B), i.e. provide oxygen to the of the proper maintenance of the system of a human body (H). Accordingly functional explanation consist of the followings a. L perform the function of B to the system of H b. B therefore explains the existence of L or H's possession of L. 2. However, there is a basic logical setback in this functional-explanatory structure. That is, since L performs B, therefore L must be an antecedent of B. However in the cause-effect explanatory structure, the existence of an effect (L) could not have anteceded that of its cause (B). Therefore, B could not have been the cause of L. 3. Nevertheless, in biology this setback can be compensated by the mechanism of natural selection in the theory of evolution. That is the W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 18 seemingly temporal ordering mismatch between B and L can be explained away within the much longer timeline within the mechanism of natural selection and adaptation found in the evolutionary process of species. 4. The missing selection and adaptation mechanism in social science: However, in social sciences there seems to be no social ecologicalselection theory available in support of its functional explanation that is comparable to the evolutionary theory in biology and ecology. If that seems to be the case, then we may have to accept Jon Ester’s suggestion that functional explanation is not applicable in social science research. 5. Revisions of functional explanation in social sciences: In social science research there are at least three formulations, which attempt to provide some sort of selection mechanism in social development processes upon which the functional explanation for social phenomena can be built. a. The concept of equilibrium in Social System Theory: The first selection mechanism supporting the functional explanation for social activities are put forth by US sociologists, such as Talcott Parsons and Robert K. Merton, who were the leading figures of the Social System Theory. The theory was one of the dominant schools in sociology in the 1960s. It advocates that human society can be conceptualized as a well-integrated social system, which is made up of numbers of subsystems or called social institutions. It is assumed that each of these subsystems will develop its own set of structure and function. Together these subsystems will work concertedly to attain a state of equilibrium for the system as a whole. And it is further assumed that this state of equilibrium of the system will maintain itself over a definite period of time. It is suggested that this “grand theory” of social equilibrium can be taken as the evolutionary basis of the selection mechanism for the functional explanation in social sciences. That is, the functional explanation for the existence of a social activity can be accessed in terms of its contributions to the maintenance of social equilibrium of the social system, which the social practice in point is embedded. In retrospect, it is common knowledge within the discipline of sociology that such a grand theory of social evolution and social equilibrium has been challenged and criticized by social scientists from the perspectives of conflict theory. As a result, the functional explanation in social sciences has to look for another more creditable conception selection mechanism as its theoretical basis. b. The “consequence law”: G.A. Cohen, a prominent Marxian philosopher in Oxford University, has put forth another attempt to provide a selection mechanism for functional explanation in social science. Instead of building a grand theory for the social ecological environment as a whole, Cohen suggests that social scientists could settle with the “consequence law”. (Cohen 1978) By “consequence law”, it refers to the “beneficial consequence” that a particular social activity could bring to its participants. And as result it would motivate its participants to continue to take part in the social activity in point W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 19 and in turn it would sustain the social endeavor as a whole. Cohen suggests, For example, within Marxian conception of relation of production or class relation, one can render a functional explanation for the existence of a particular form of relation of production by the consequence it entailed. That is, a particular relation of production will sustain itself over time (or in Marian term reproduce) as long as it can render its participants “good enough” beneficial consequences that they would remain within that relation of production and rather than overthrow it, i.e. wage a class revolution. c. Functional explanation by institutional persistence: In recent decades, there are several further revisions on the selection-mechanism basis for the functional explanation in social sciences. (Kincaid, 1994; 2007; Pettit, 2002) These revisions aim to further retreat from the theoretical claim of providing an overall evolutionary theory of the social system for the functional explanation in social science. Instead, they further revise that i. Persistence as explanandum (the effect to be explained): Both Kincaid (2007) and Pettit (2002) have suggested that functional explanation for the existence of a particular social activity should simply aims to provide an explanation for the persistence or reproduction of the social activity in point, instead of rendering any exhaustive causal mechanism of how the social activity come about. ii. Distinction between current persistence and origin of the explanandum: Both Kincaid (2007) and Pettit (2002) have further suggested that in functional explanation of the existence of a social activity, the explanandum should only be it persistence or reproduction in a particular point in time rather than to trace the whole evolutionary process of the social activity back to its origin of formation. iii. Institutional embeddedness: In functional explanation, the explananda are no long rational actions deliberately carried out by agents as presupposed in model of rational-choice explanation, instead they are social persistence and resilience found in institutional contexts. Therefore, it is assumed that functional explanation must be sensitive to the historical and institutional contexts in which the explananda are embedded. (Kincaid, 1994; 2007; Pettit, 2002) iv. Distinction between optimal and stable consequences: Kincaid (1994; 2007) has further underlined that the beneficial consequences in use to provide functional explanation for social activities should not be defined in optimal terms as some rational-choice theorists insisted. Instead, the beneficial consequences in functional explanations should only be defined in terms of “stable consequences” or in Herbert Simon’s terms “satisficing” or “good enough” consequences. v. Distinction between particularistic and universalistic explanations: Given all these revisions, the model of functional explanation in its present form could not have claimed to render a universal and exhaustive explanation to its explanandum. All it could claim is W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 20 that it has provide one of the contributing factors to the persistence of a particular social activity within a particular institutional context in ea particular point in time. d. The state of the art of the functional explanation in social science: Given the revisions reviewed above, the current functional explanation model may be summarized as follows. other factors Function at t0 Social Action Function at tn Persistence Institutionalization Persistence Contextual Embeddedness InstitutionalizationPersistence G. Policy as Political Bargain and Compromise to Meaning and Value Conflicts 1. David Easton’s conception political system: Easton differentiates his conception of public policy as authoritative allocation of values into three components of a political system a. Input of political demands and supports b. Conversions of input into authoritative allocation of values c. Output of policy 2. Gabriel A. Almond functional categorization of political system a. Input functions i. Political socialization and recruitment ii. Interest articulation iii. Interest aggregation iv. Political communication b. Output functions i. Rule-making ii. Rule-application iii. Rule adjudication 3. Dahl and Lindblom’s conception of political bargaining in polyarchy a. Robert Dahl’s of polyarchy i. Two theoretical dimensions of democratization - Public contestation: It indicates “the extent of permissible opposition, public contestation, or political competition” of the government. (Dahl, 1971, p. 4) - Inclusiveness of participation: It indicates “the proportion of the population entitled to participate on a more or less equal plane in controlling and contesting the conduct of the government.” (Dahl, 1971, p. 4) W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 21 ii. The concept of polyarchy: “Polyarchy may be thought of as relatively (but incompletely) democratized regimes, or to put it in another way, polyarchy are regimes that have been substantially popularized and liberalized, that is, highly inclusive and extensively open to public contestation.” (Dahl, 1971, p. 8) b. Social pluralism and political bargaining as necessay conditions of polyarchy i. Social pluralism: “Polyarchy requires a considerable degree of social pluralism, that is, a diversity of social organizations with a large measure of autonomy with respect to one another.” (Dahl and Lindblom, 1992, P. 203) ii. Political bargaining as necessity for polyarchy in social pluralism In social pluralism, “if leaders agree on everything they would have no need to bargain; if on the nothing, they could not bargain. Leaders bargain because they disagree and expect that further agreement is possible and will be profitable. …Hence, bargaining atkes place because it is necessary, possible, and thought to be profitable.” (Dahl and Lindblom, 1992, p. 326) 4. Corporatism: Criticism on pluralism in policy studies a. Schmitter’s juxtaposition of concepts of pluralism and corporatism i. “Pluralism can be defined as a system of interest representation in which the constituent units are organized into an unspecified number of multiple, voluntary, competitive, nonhierarchically ordered and self determined ( as to type or scope of interest) categories which are not specifically licensed, recognized, subsidized, created or otherwise controlled in leadership selection or interest articulation by the state and which do not exercise a monopoly of representational activity within their respective categories. (Schmitter, 1979, p. 15) ii. “Corporatism can be defined as a system of interest representation in which the constituent units are organized into a limited number of singular, compulsory, noncompetitive, hierarchically ordered and functionally differentiated categories, recognized or licensed (if not created) by the state and granted a deliberate representational monopoly within their respective categories in exchange for observing certain controls on their selection of leaders and articulation of demands and supports. (Schmitter, 1979, p. 13) b. Liberal and authoritarian corporatism i. Liberal corporatism: Liberal/societal corporatism refers to the kind of interest-mediation mechanism constituted by liberal democratic states mainly between interest organizations of the labor and the capital. It aims to construct a kind of welfare corporatism or welfare state within which two major interests namely the labor and the capital can work out some collaborations under the mediation of the state; e.g. Scandinavian welfare state and post-WWII welfare state in UK. ii. Authoritarian corporatism: Authoritarian/state corporatism refers to the kind of interest-mediation mechanism of constructed by bureaucratic-authoritarian state among interest organizations W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 22 licensed by the state. Within authoritarian corporatism, the state is more or less secluded from societal and political pressures and can absolve chosen interest groupings into the corporatism to legitimate and/or facilitate its ruling, e.g. authoritarian regimes established in south America in the 1960s; regimes in the 1970s in east Asia, especially the four little dragon. H. Policy as State Apparatus in Resolving Societal Conflicts or Struggles (To be discussed in Topic 3) I. Education Policy as text interpreted by actors, mediated and enacted by actors in institutional settings (To be discussed in Topic 7-8) J. Synthesizing Models of Explanation in Policy Studies (Level I) Cognition Information /E Causal Explanation(in-order-to Explanation) Social Action Intentional Explanation (because-of explanation) Other Factors (Level II) D Teleological Explanation Quasi-teleological Explanation (Functional Explanation) Persistence Function t0 (Level III) Function tn Institutionalization Contextual Embeddedness W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 23 (III) Discursive-Critical Perspective in Policy Studies A. Argumentative and Persuasive Turns in Policy Studies 1. Public policy as argumentative and persuasive practices a. Redefining the nature of public policy: “As politicians know too well but social scientists too often forget, public policy is made of language. Whether in written or oral form, argument is central in all stages of the policy process.” (Majone, 1989, p.1) b. Redefining the role of the policy analysts: “In a system of government by discussion, analysis - even professional analysis has less to do with formal techniques of problem solving than with process of argument. The job of analysts consists in large part of producing evidence and arguments to be used in the course of public debate. Its crucial argumentative aspect is what distinguishes policy analysis from the academic social science on the one hand, and from problem-solving methodologies such as operations research on the other. … They must persuade if they are to be taken seriously in the forums of public deliberation. Thus, analysts, like lawyers, politicians, and others who make a fundamental use of use of language, will always be involved in all the technical problems of language, including rhetorical problems. (Majone, 1989, p. 7) 2. Public policy as practice of persuasion 1. Redefining the nature of public policy: “All our talk of ‘making’ public policy, of ‘choosing’ and ‘deciding’, loses track of the home truth … that politics and policy making is mostly a matter of persuasion. Decide, choose, legislate as they will, policy makers must carry people with them, if their determinations are to have the full force of policy. …To make policy in a way that makes it stick, policy makers cannot merely issue edicts. They need to persuade the people who must follow their edicts if those are to become general public practice.” (Goodin et al., 2006, p. 5) 2. Redefining the core of the discipline: “Not only is the practice of pulic policy making largely a matter of persuasion. So is the discipline of studying public policy making aptly described as itself being a ‘persuasion’. It is a mood more than a science, a loosely organized body of percepts and positions rather than a tightly integrated body of systemic knowledge, more art and craft and genuine ‘science’.” (ibid) B. Discursive Perspective in Policy Studies 1. Locating the level of study for policy discourse a. The concept of discourse has become popular in social sciences in past decades. As the concept being used by various disciplines in social sciences, the meanings of the concept have become heterogeneous if not chaotic. b. At conversation level, the concept of discourse can refers to speech act, language use, or parole. For example in classroom discourse study, discourse is taken as speech act and speech exchange W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 24 between teachers and students in the classroom context. c. At institution level, discourse can refers to cognitive, regulative and normative rules governing the circulation and practice of ideas, concepts, categories and representations of social meanings within a social institutional domain. For examples, in medical institution, discourse may take the form of a certification issued by a doctor to a patient indicating the health condition of the latter and the whole institutional configuration making this certification effective; and in educational institution, discourse may take the form of a certificate issued by government to a student certifying passing of an examination of the latter and the whole institutional configuration making this certification effective. d. At socio-cultural system level, discourse can refers to the dominance or hegemony governing the circulation and/or practice of ideas, concepts, categories and representations of social meanings in a society. For example, the discourses of neo-liberal capitalism or socialism in economy system; discourse of liberal democracy or proletarian dictatorship in political system; etc. 2. The conception of discourse in public policy a. Frank Fischer defines “Discourse …is an ensemble of ideas and concepts that give social meaning to social and physical relations.” (2003, p. 90) b. David Howarth defines Discourse refers “to historically specific systems of meaning which form the identities of subjects and objects.” (2002, quoted in Fischer, 2003, p. 73 c. Maarten Hajer defines discourse as “a specific ensemble of ideas, concepts, and categories that are produced, reproduced, and transformed to give meaning to physical and social relations.” (1995, quoted in Fischer, 2003, p. 73 e. Taken together these conceptions of discourse, policy discourse can then be characterized as a historically specific ensemble of ideas, concepts and categories which gives meaning to physical and social relations and forms identities of subjects and objects within a particular policy domain and/or around a specific policy issue. For example, the neo-liberalism in public policy; the “Washington consensus” in fiscal policy; the welfare state or the workfare state in welfare policy; comprehensive- egalitarianism or quasi-market discourse in education policy. C. Michel Foucault’s Theory of Discourse 1. Conception of Statement a. The statement – the constituent unit of a discourse “The statement is not the same kind of unit as the sentence, the proposition, or the speech act…The statements is not …a structure (i.e. a group of relations between variable elements...); it is a function of existence that properly belong to signs and on the basis of which one may then decide, through analysis or intuition, whether or not they ‘make sense’, according to what rule they follow one another or are juxtaposed, of what they are the sign, and what sort of act is carried out by their formulation (oral or written).” (Foucault, W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 25 1972, p. 86-87) b. Accordingly policy statement can then be defined as a specification or even a prescription (in oral or written format) circulating in a particular public policy domain. It defines the “conditions of existence” the objects in the specific public policy domain are qualified to obtain. For examples, policy statements identify the insane person, the infected patient, the welfare dependent, the convicted criminal, the university dropout or graduate, the EMI-capable, the benchmarked English teacher; and they also stipulate the institutional treatments to be imposed on them. 2. Conception of discourse a. A discourse “is the totality of all effective statements (whether spoken or written). ... Description of discourse is in opposition to the history of thought. There…a system of thought can be reconstituted only on the basis of a definite discursive totality. …The analysis of thought is always allegorical in relation to the discourse that it employs. Its question is unfailingly: what is being said in what was said? …what is this specific existence that emerges from what is said and nowhere else?” (Foucault, 1972, p. 27-28) “We can now give a full meaning to the definition of ‘discourse’. …We shall call discourse a group of statements in so far as they belong to the same discursive formation. …It is made up of a limited number of statements for which a group of conditions of existence can be defined.” (p. 117) b. Hence, a policy discourse is a totality and unity of effective policy statements within a public policy domain in specific historical, cultural, and socio-economic contexts. For example, the quasi-market discourse on education reforms implemented by capitalist states in developed countries in the last decade of the 20th century can be construed as a totality of effective policy statements which stipulate the underlying principles as well as the operational mechanism of the schooling system in these countries. 3. Foucault’s Theory of Discursive Formation Foucault differentiates the formation of a discourse into four interrelated parts. a. The Formation of Object: ii. Mapping the surface of the emergence of the object ii. Describing the authorities of delimitation iii. Analyzing the grids of specification b. The Formation of Enunciative Modality i. Identifying who is speaking, who is accorded the right to use this sort of language, who is qualified to do so. ii. Describing the institutional sites from which the discourse is made and form which the discourse derives its legitimate source and point of application iii. Analyzing the position of the subject, in which s/he occupies in relation to the various domains and groups of objects c. The Formation of Concepts: the formation of the organization of the field of statements where they appeared and circulated i. Identifying the forms of succession, e.g. W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 26 - Orderings of enunciative series - Types of dependence of the statement - Rhetorical schemata according to which groups of statements may be combined ii. Identifying the forms of coexistence - Field of presence - Field of concomitance - Field of memory iii. Identifying the procedures of intervention that may be legitimately applied to statements, e.g. technique of rewriting , method of transcribing, mode of translating, means of transferring, method of systematizing d. The Formation of Strategies or theoretical and thematic choice i. Determining the points of diffraction of discourse - Point of incompatibility - Point of equivalence - Point of systematization ii. Analyzing the economy of the discursive constellation iii. Analyzing the other authority, e.g. functional to fields of non-discursive practice, observing the rules and processes of appropriation of discourse 5. Foucault’s Theory of Power/Knowledge and Discourse a. The relation between discourse and power: “Discourse can be both an instrument and an effect of power… Discourse transmits and produces power; it reinforces it.” (Foucault, 1978, 101, my italic) b. The concept of power/knowledge i. “It is in discourse that power and knowledge are joined together” (Foucault, 1978, p. 100) and constitute what Foucault conceptualized the power/knowledge. ii. “We should admit … that power and knowledge directly imply one another; that there is no power relation without the correlative constitution of a field of knowledge, nor any knowledge that does not presuppose and constitute at the same time power relations. These power/knowledge relations are to be analyzed, therefore, not on the basis of a subject of knowledge who is or is not free in relation to the power system, but, on the contrary, the subject who knows, the objects to be known and the modalities of knowledge must be regarded as so many effects of these fundamental implications of power/knowledge and their historical transformations. In short, it is not the activities of the subject of knowledge that produces a corpus of knowledge, useful or resistant to power, but power/knowledge, the processes and struggles that traverse it and of which it is made up, that determines the forms and possible domains of knowledge. (Foucault, 1977, p. 28) D. Critical Discourse Analysis 1. Assumptions of Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA): As a research approach, CDA has assigned numbers of particular features to the W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 27 understanding of discourse a. Discourse as social practice: Discourse is no longer construed as individual language use in forms of text or talk, but as social practices which implies i. Representation and/or expression of meaning and value ii. Acts upon the world iii. Acts upon social relations between human beings b. Constitutive nature of discourse: Construed as social practice, discourse therefore takes on a constitutive nature. In other words, human beings use discourse to construct the worlds or realities around them. This constitutive nature of discourse may manifest in at least three aspects i. Ideational construction: “Discourse contributes to the construction of system of knowledge and belief.” (Fairclough, 1992, p. 64) For example, discourse of science contributes to the construction of the material world around us so are discourse of myths or religion. ii. Relational construction: “Discourse help construct social relationship between people.” (ibid) For example, liberaldemocratic discourse derived from the Enlightenment contributes to the constitution of the political realities of modern societies. iii. Identity construction: Discourse contributes to the construction of social subjects, self and social identity. For example, the identity of citizenship is constructed through the liberal-democratic discourse in the past three centuries in human societies. c. Dialectic relationship between discourse and the social structure “It is important that the relationship between discourse and social structure should be seen dialectically if we are to avoid the pitfalls of overemphasizing on the one hand the social determination of discourse, and on the other hand the construction of the social in discourse.” (Fairclough, 1992, p. 65) In other words, the dialectic perspective in the relation between discourse and social structure takes both social determination and social construction into to consideration and assumes them to be in a interactive and mediating relation. d. Discourse is historical: CDA takes discourse as concrete social practice in particular historical and socio-cultural contexts. Hence, analysis of contexts, where the discourse takes place, is an essential part of CDA. e. Ideological effect of discourse: The core question CDA attempts to explore how discourse serves as means to legitimatize and reproduce prevailing power relations and the ideological effects formed in different forms of social dominations, such as class, race and gender. Hence, to wage critique on inequalities in power relations and social distortions and biases in ideological configurations is what makes CDA “critical”. 2. Fairclough’s three-dimensional framework of CDA a. Three-dimensional analytical framework of CDA (Figure 1) i. Text analysis: This dimension of discourse analysis includes - Analyses of text W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 28 - Analysis of textuality - Analysis of intertextuality ii. Discourse analysis: It covers analysis of the process of production, distribution and consumption of a discourse. In other words, it basically correspond Foucault’s conception of discursive formation. iii. Ideology analysis: This aspect of discourse analysis aims to reveal the ideological effect embedded and/or constituted in a particular discursive practice. By ideological effect of a discourse, it refers to effect of a discourse in legitimating and reproducing prevailing inequalities in power relations and social distortions and biases in social-cultural practice. Furthermore, as an ideological effect of a discourse has achieved the cognitive status of “taken for granted” or “common sense” among participants of a discourse, then it has constituted, what Gramsci conceptualizes, hegemony. Hegemony is “an ideological complex” (Gramsci, 1971; quoted in Fairclough, 1992, p. 92), which constitutes “leadership as well as domination across the economic, political, cultural and ideological domains of a society.” (Fairclough, 1992, p. 92) b. The mediating function of discursive practices between textual practices and social-cultural practices. “Critical discourse analysis is very much about making connections between social and cultural structures and processes on the one hand, and properties of text on the other.” (Fairclough and Wodak, 1997, p. 277) Critical discourse analysts have construed the dimension of discursive practice as the mediator between the two. They have characterized the connection to be mediating in nature. In other words, the connection is neither direct nor deterministic but in the form of dialectic and interactive. W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 29 Figure 1 Analytical Framework of Critical Discourse Analysis E. Policy Studies as Social Critiques 1. Conception of social critique and critical social science a. According to Jurgen Habermas, a prominent figure of Critical Theory in Germany, the primary concern of critical social scientists and social critiques in general is to refute the assumption of empirical-positivistic social researcher that social regularities revealed in social researches are given facts comparable to those natural facts discovered in natural science. Accordingly, they must reflect on the legitimation foundation, which the prevailing social regularities are built upon. More specially, they have to go beyond the status quo and try hard to reveal the possible "power-hypostatized" social relations and "ideologically-frozen" social discourses at work. (1971, P. 310) b. Applying these ideas to policy studies, critical policy studies can then be construed as attempts to unmask the possible i. distorted social relations hypostatized in specific public policies, which are bias in favor of the dominants and/or against the dominated, and ii. distorted social discourses frozen in particular policy arenas, that ideologues of the advantageous have forged in order to mystify and/or rationalize the prevailing biases against the disadvantaged. c. As a result, the objective of critical social science, including critical policy studies, is to emancipate i. the disadvantageous and dominated from distorted and biased social relations instituted in prevailing social arrangements; ii. the articulations and voices of the disadvantageous and dominated, which have been silenced in the ideologies forged by the ideologues of the dominants. W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 30 2. Aspects of criticality in policy studies a. Critique on policy issues and frames: Critical policy researchers can set out to reflect on the way a policy issue is formulated and framed by the dominant policy discourse of the state. And see if there are any relational and ideological distortions embedded in a particular formulation of policy issue. b. Critique on policy stances of specific parties: Critical policy researchers can reflect on the possible relational distortion embedded in the discursive process of a particular policy arena. That is, they can assess the chances and capacities that different interest parties possess in articulating their concerns and in redressing their grievances. Furthermore, critical policy studies can also reflect on the ideological distortions found in the arguments formulated and proclaimed by different parties concerned. c. Critique on policy context: The third aspect of criticality in policy studies is to reflect on the macro socio-historical context and/or meso institutional context, form which a particular policy issue is originated. More specifically, it can assess whether there is any relational and ideological distortions embedded in these context, which give rise to the policy issue at point. d. Critique on policy practice: The final aspect of criticality in policy studies is to reflect on the possibilities of transformation and emancipation that a policy practice can bring about in rectifying the relational and ideological distortions embedded in a policy phenomenon. F. Education Policy in Critical Discourse Perspective: Discursive Analysis of Lifelong Learning Education Reform in HKSAR 1. In search of discursive object of HKSAR education reform a. In terms of policy document b. In terms of temporal demarcation c. In terms of discursive theme: Lifelong learning? 2. Analysis of the Enunciative Modality in HKSAR education reform a. Speakers and the their positions and/authority to speak b. Languages used in discourse c. The institutional sites within which the discourse takes place 3. Understanding the discursive concept of HKSAR education reform a. Understanding the formation of discursive concept in academic discourse: Two versions of lifelong long education reforms i. Lifelong learning education reform for economic rationalism ii. Lifelong learning education reform for social inclusion and political empowerment b. Understanding the formation of discursive concept in global policy context i. Conceptual and methodological qualifications ii. Empirical comparisons c. Understanding the formation of discursive concept in HKSAR: In paradigmatic comparative perspective W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 31 4. Analysis of the discursive strategies of HKSAR education reform a. Points of equivalence and systematization: The construction of the quasi-market mechanism b. Points of incompatibility c. Economy of discursive constellation of public policy of HKSAR Government 5. Analysis of the ideological and hegemonic practice of the discourse of HKSAR education reform a. Discursive domination / hegemony of market system and bureaucratic- administrative system over education system b. Distortions and bias against communicative-communal discourse in education c. Distortion and bias against critical-emancipatory discourse in education d. Suppression and bias against the discourse of the education profession W.K. Tsang Policy Studies in Education 32