Classroom management - Students, Alumni and Friends

Classroom Management

When it comes to teaching, nothing affects success quite like classroom management.

Langness 1

Unfortunately, when many first-year teachers get out into the field, they find that they are woefully unprepared for managing a classroom of students. It is therefore quite important that future teachers work to understand what goes into management, as well as compile a list of strategies that they could use to implement in their own classrooms.

Management is often thought of primarily as discipline in the connotative sense—the consequences that teachers impose on students when they misbehave. In reality, management relies most heavily on motivation and the student-teacher relationship. Motivation is a complex subject, and is the driving force behind why students behave in one way or another. For example, a student may be motivated to do his work on time, listen to the teacher, and in general behave quite well. Another may be motivated to disrupt the class by entertaining his friends and goofing off. To better understand motivation, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs must be considered, as well as the different types of motivation.

Maslow was a psychologist who studied the motivation of human needs. His hierarchy is often pictured as a pyramid, at the base are the fundamental human needs to survive—food, shelter, and safety. Next up are social needs, such as the need to belong and find friends. The third tier is made up of ego needs such as self-esteem and feeling capable and loveable. It is only after all of these needs are fulfilled that a person can even begin to focus on academic achievement. For example, if a student comes to school hungry she will not be engaged in the learning process because her mind will be focusing instead on the fact that she needs food. This need must be taken care of before she can succeed academically. This is the primary reason behind school breakfast programs and the Free and

Reduced Lunch program.

Langness 2

Motivation can be broken down into two different types—intrinsic and extrinsic. Intrinsic motivation comes from the satisfaction of doing the job itself, or because the student finds the task to be worthwhile. It does not require any type of outside reward, because the job itself is rewarding.

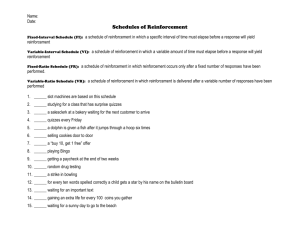

Extrinsic motivation, on the other hand, comes with either a reward or a punishment. Students are motivated by the promise of either something desirable or undesirable. These are especially important to keep in mind when developing discipline strategies.

The teacher-student relationship is the other component to successful management. If the student feels connected to and valued by the teacher, they are much more likely to behave well and do things for the teacher. Conversely, a teacher who is distant from her students or does not have a positive relationship built up cannot expect them to willingly do as she asks. It should be noted that this does not mean that teachers should strive to be their students’ friend. Rather, they should work to let students know that they genuinely care and want them to succeed, that they will provide any support or help required, and that they will create a safe and positive environment.

Once these two things have been explored, the teacher can begin to think about the actual management strategies to use. Most of these will be built around the premises of operant conditioning and the use of positive and negative reinforcement and punishment. Experts suggest that teachers use more reinforcement than punishment, as punishment can very easily backfire or seem too harsh.

Reinforcement strategies should take into account the motivation of students. For example, if students are motivated in their disruptive behavior by the desire for attention, then a lecture from the teacher in front of the whole class (though it is negative attention) will still reinforce the behavior. The teacher should instead take a negative reinforcement approach and withhold attention from the student when they are taking part in the disruptive behavior. Without the reward of attention, the behavior will in theory eventually subside. An example of positive reinforcement is a teacher giving a positive

Langness 3 complement to a student for desirable behavior. The student is more likely to repeat the desired behavior if they believe that they will be recognized and commended.

There are several strategies that teachers can use to create a classroom environment that functions smoothly and efficiently. Teachers should establish a routine and set of procedures at the beginning of the year and stick with them—when students know what they are to expect, they will be less likely to be disruptive. The same goes with rules and behavior expectations. If the teacher lays out clearly the classroom rules and expectations, then is consistent with consequences, the students will know what is expected of them. Another strategy goes along with building relationships, and that is to learn and remember students’ names as soon as possible. Teachers should also never underestimate the effect that a clean and organized environment will have on student behavior, and so keeping things clean and tidy can definitely be considered a management strategy.

Even with all of these strategies and reinforcement, it is inevitable that there will be a few students who are still incorrigibly disruptive. For these students, teachers must make extra effort.

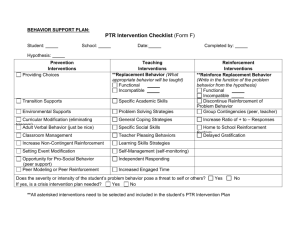

Rather than relying solely on punitive measures, often a behavior contract is effective. Problem students work with the teacher to decide on a set of desirable behaviors and the consequences that will occur if the students do not uphold their contract. This gives the student a more personal ownership of his behavior. These contracts also allow the teacher to monitor student behavior, and they can be modified as the need arises.

Another trend that is on the rise in classroom management is to give the class as a whole more ownership of their classroom rules. They work with the teacher at the beginning of the year to set up the expectations for behavior as well as the consequences. Students then monitor both their own behavior and the behavior of the class. Though the teacher has the final say in giving consequences, students are taking charge of their own behavior, and most will rise to the challenge of selfmanagement.

Langness 4

As a future teacher myself, these are all things that I am keeping in mind as I think about the management of my own classroom. Motivation and the hierarchy of needs is something to keep in the forefront of my mind. If a student is displaying disruptive behavior, rather than immediately moving towards punishment, I should instead assess the situation and find out if there are any outside factors that are influencing the behavior. Building relationships with my students is also at the top of my list, letting them know that my classroom is a safe environment, that I care, and that I will provide support. I can do this by learning names quickly, checking in on students, learning about their hobbies and passions, and being in-tune with what is going on in their lives. Classroom routines and consistency are also things that I plan on having, so that students know exactly what to expect and when. Though this may seem like it will create a boring environment, I think it will actually create a more comfortable and work-conducive atmosphere since the students will not be caught off-guard or distracted by something new. I think there is value in having students help decide on classroom rules and punishments, though they should definitely not take the place of the teacher when it comes to authority. I also think it is especially important to remember that no two classrooms will look exactly alike, and so striving for a cookie-cutter model is not going to cut it. From year to year there will be different students with different motivators and different behaviors. Though the underlying ideas will remain the same, I will constantly be having to adapt and modify my strategies to be effective.

Langness 5

Works Cited

Campbell, Patricia Shehen and Scott Kassner, Carol. Music in Childhood. Stamford, CT: Schirmer,

Cengage Learning, 2014.

Hoff, Kathryn E., and Ruth A. Ervin. “Extending Self-Management Strategies: The Use of A Classwide

Approach.” Psychology in the Schools 50.2 (2013): 151-164

Lloyd, Claire, Sandra Bruce, and Kirsty Mackintosh. “Working On What Works: Enhancing Relationships in the Classroom and Improving Teacher Confidence.” Educational Psychology in Practice 28.3

(2012): 241-256