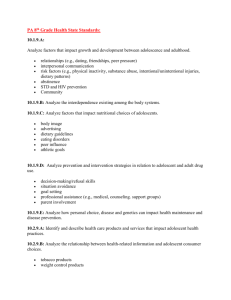

Adolescent Alcohol Use

advertisement