Copy of Sharo...r Thesis

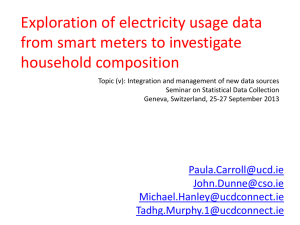

advertisement

Master Programme in Economic History

Household consumption in China on the rise: Can China

buy growth?

Sharon J. Riley

aeh10sri@student.lu.se

Abstract: This paper seeks to examine trends in Chinese household consumption. It is

comprised of a two-fold study, which undertakes both an exploratory and an explanatory

approach. First, an analysis into the nature of household consumption examines trends in

purchasing habits. Specifically, data on the consumption and prevalence of durable household

goods and major food commodities is gathered to establish both the yearly demand for such

products, as well as to establish whether demand in the consumer market is met by domestic

production. Second, an explanatory analysis of household consumption attempts to glean more

insight into which factors may potentially induce increases in Chinese household consumption.

This study is undertaken in response to the suggestion that the current leadership of China has

undertaken a fundamental shift in government policy which seeks to promote consumptiondriven rather than export-led growth as a means to sustained transformation and long term

economic growth.

The results suggest, coinciding with past studies, that government expenditure on social

programs (welfare, pensions, etc) has a significant impact on household consumption, supporting

theories of precautionary savings and their implicit effects on consumption levels.

Key words: China, household consumption, economic growth, domestic market, precautionary

saving

EKHR11

Master thesis (15 credits ECTS)

June 2011

Supervisor: Christer Gunnarsson

Examiner:

Page 2 of 58

Contents

1

Objective................................................................................................................................................................ 4

2

Background and justification .............................................................................................................................. 4

3

Contribution of Study.......................................................................................................................................... 8

4

China’s Economic Growth; Pre-reform to present ........................................................................................ 9

5

Theories of Household Consumption ............................................................................................................11

6

Part I - Exploratory Study of Consumption of Household Goods ...........................................................13

6.1

Data .............................................................................................................................................................14

6.1.1

Household Commodities ................................................................................................................14

6.1.2

Food Commodities ..........................................................................................................................15

6.2

Limitations of Data ...................................................................................................................................16

6.3

Methods ......................................................................................................................................................17

6.3.1

Household Commodities – durable goods ..................................................................................17

6.3.2

Food Commodities ..........................................................................................................................19

6.4

Results .........................................................................................................................................................20

6.4.1

Colour Televisions ...........................................................................................................................20

6.4.2

Bicycles ..............................................................................................................................................23

6.4.3

Cameras .............................................................................................................................................26

6.4.4

Electric Fans .....................................................................................................................................28

6.4.5

Comments .........................................................................................................................................30

6.5

7

Food Commodities ...................................................................................................................................31

6.5.1

Sugar...................................................................................................................................................31

6.5.2

Edible Vegetable Oil .......................................................................................................................32

Part II - Explanatory Study: Household Consumption on the Rise ..........................................................35

7.1

Data .............................................................................................................................................................35

7.2

Data Limitations ........................................................................................................................................36

7.3

Methods ......................................................................................................................................................36

7.4

Definitions of Variables ...........................................................................................................................37

7.4.1

Dependent Variable .........................................................................................................................37

7.4.2

Explanatory Variables .....................................................................................................................38

7.5

Modifications of Start Model ..................................................................................................................41

7.6

Results .........................................................................................................................................................43

8

Discussion and Relation to Theory .................................................................................................................46

9

Conclusion...........................................................................................................................................................50

10

Appendix .........................................................................................................................................................51

10.1

Results of Exploratory Study ..................................................................................................................51

Sharon Riley - Master Thesis – Lund University School of Economics and Management

Page 3 of 58

11

10.1.1

Bicycles ..............................................................................................................................................51

10.1.2

Cameras .............................................................................................................................................52

10.1.3

Electric Fans .....................................................................................................................................52

10.2

Descriptive Statistics .................................................................................................................................53

10.3

Alternate Model .........................................................................................................................................55

Works Cited ....................................................................................................................................................56

Sharon Riley - Master Thesis – Lund University School of Economics and Management

Page 4 of 58

1 Objective

The objective of this paper is to examine the trends in Chinese domestic household consumption

over the past three decades. Much literature has focused on the suggestion that domestic

consumption in China has not been at satisfactorily high levels, and lags behind that of other

countries at a similar development stage. It will be of interest in this thesis to look more closely at

the nature of household consumption.

This will be a two-fold study: first, an exploratory study into the nature of household demand for

durable household commodities and major foodstuffs will be completed. In this portion of this

thesis, the domestic demand will be estimated based on available data and will be compared with

data on imports and exports where possible. Two separate methods of calculating domestic

demand will be utilized and compared.

In the second portion of this paper, an attempt will be made to contribute an explanatory study

of the factors influencing increasing household consumption. Specifically, stated policy shifts of

the Chinese government, in combination with a myriad of economic and demographic factors

will be analysed. Of particular interest is the role of the government in stimulating consumption,

be it through stated policy shifts or through social spending.

This discussion of patterns in household consumption leads to a larger question surrounding

whether current consumption levels in China are at a sufficiently high level to ensure long term

economic growth.

2 Background and justification

China is on course to be one of the major consumer markets in the world, with some sources

predicting it will be the world’s third largest consumer market by 2020 (Woetzel et al., 2009). The

domestic market in China has the possibility to be a huge driver in the engine of economic

growth in both the Chinese and the world economy, based on its sheer size alone. With the

wages of even the lowest skilled labourers rising (see Figure 2-1), it seems obvious that domestic

Sharon Riley - Master Thesis – Lund University School of Economics and Management

Page 5 of 58

consumption will increase. This is not only a function of consumer purchasing power. In 2004,

China’s top political leadership made the decision to fundamentally alter the country’s growth

strategy. In place of the investment and export-led development that has been credited for the

rapid economic growth to date, they endorsed transitioning to a growth path that relied more on

expanding domestic consumption (Lardy, 2006; Aziz & Cui, 2007). It is with this policy shift in

mind that it appears relevant to undertake an analysis of changes in Chinese domestic

consumption patterns over the past three decades; during the period of rapid transformation of

the Chinese economy. First, it is of particular interest how household consumption patterns have

changed over time and what has influenced this trend. When examining household consumption

on goods, it is of specific interest whether domestic demand is met by domestic output. A

significant quantity of literature and media has focused on the Chinese consumer’s demand for

luxury goods, many of which are imported. Research into consumer preferences in the past has

unveiled, at least for some electronic goods, preferences for imported goods (Doran, 2002). It is

possible then, that rising consumerism in China could greatly affect China’s balance of trade, as

Chinese consumers may prefer imported goods (due perhaps to perception of differences in

quality). The magnitude of this effect is uncertain, as it may apply only to high-earning urban

residents and not be a trend applicable to the entire population. Regardless, the preferences of

Chinese consumers could have large impacts on the long-term sustainability of economic growth

and trade balances in China. Unfortunately, a survey of individual consumer preferences and

spending patterns in China is outside the scope of this masters thesis. Instead, the demand for

domestically produced goods will be disaggregated from numerous series of available data, and

trends examined.

Sharon Riley - Master Thesis – Lund University School of Economics and Management

Page 6 of 58

100000

Total

10000

Farming, Forestry,

Animal, Husbandry,

and Fishery

Mining and Quarrying

1000

Manufacturing

1978

1985

1987

1989

1991

1993

1995

1997

1999

2001

2003

2005

2007

100

Figure 2-1 - National average yearly wages (yuan) of Chinese workers in traditionally lower paid sectors and overall

total average, 1978 – 2008 (natural logarithm applied) Source: China Statistical Yearbook

Chinese households have had a historically low ratio of private consumption relative to GDP and

it appears to be declining (see Figure 2-2). This declining trend in the share of GDP that is made

up by private consumption is supported by trends in household finances, with the average

household choosing to save approximately 25% of their disposable income in 2007, compared

with only 11 percent in 1990 (Baldacci, et al., 2010). Earlier estimates of aggregate savings stated

that the national savings rate was as high as 50% of GDP in 2005 (Lardy, 2006).

Household Consumption

Government Consumption

1952

Fixed Capital

1980

2009

Changesin Inventories

Net Exportof Goodsand Services

0%

20%

40%

60%

80% 100%

Figure 2-2 – Share of GDP by expenditure approach

Sharon Riley - Master Thesis – Lund University School of Economics and Management

Page 7 of 58

Much research has been conducted to explore the origins of these behaviours, with many

researchers believing that Chinese households have traditionally high savings rates, particularly in

rural areas, due to poor social programs and uncertainty as to how a household could handle a

crisis – be it health related, due to sudden unemployment, or otherwise. Many policy makers have

suggested that initiatives on behalf of the Chinese government to increase social spending, and

thus increase the confidences of Chinese households in their ability to survive in the face of

uncertainty, would have a direct effect on rates of private consumption (Baldacci, et al., 2010;

Barnett & Brooks, 2010; Fang, 2009). Recognition of this dilemma has been evident in recent five

years plans as well as the stimulus package introduced by the government in response to the 2008

global economic crisis (Cai, Wang, & Zhang, 2010). Private consumption in China has been

increasing in recent years (see Figure 2-3). It is of interest which factors in China have led to this

increased household consumption over the past two to three decades and, also, whether these

increases have been deemed sufficient to sustain long term economic growth.

100000

10000

All Households

Rural

1000

Urban

1978

1980

1982

1984

1986

1988

1990

1992

1994

1996

1998

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

100

Figure 2-3 - Average yearly household consumption (yuan) in Chinese households (natural logarithm applied), 1952 –

2009

Source: China Statistical Yearbook

China is indeed on course to become a dominant consumer market in the world in the coming

decades, as a result of both an increasing population and increasing consumerism. It is important

to note, however, that China’s private consumption accounts for only 36% of GDP (the lowest

of any major economy in the world), compared with 70% in the US (Woetzel et al., 2009). With

rising wages and subsequent increases in demand for consumer goods, particularly in urban areas,

Sharon Riley - Master Thesis – Lund University School of Economics and Management

Page 8 of 58

it seems pertinent to examine both trends in household consumption, as well as the Chinese

demand for goods manufactured in China. Certainly an ever-expanding consumer base combined

with large increases in per capita disposable income has the potential to alter the current growth

trajectory of the Chinese economy.

3 Contribution of Study

Although Chinese economic growth has been a prominent topic in both the popular media and

the world of academia since China first began to assert itself as a major player in the world

economy, relatively little literature has been published focusing on the origin of the household

goods purchased by Chinese consumers.

This is due in part to the tradition of Chinese

households to be frugal consumers who purchase relatively few goods compared to other

nations; China has not traditionally been perceived as an important consumer base and was

certainly not viewed as an important destination for exporting consumer goods. However, a

substantial hurdle to a study examining whether Chinese consumers are buying goods produced

domestically or abroad lies in the availability of data explicitly dealing with these questions. This

thesis will serve as an exploratory study of the data available, seeking to construct a data set to be

able to observe general trends in the consumption of domestically and foreign produced goods.

In addition, though the lackluster performance of Chinese domestic consumption has been

deeply analysed, with scholars citing declining consumption ratios and declining household

consumption levels when compared with the growth of investment and the GDP (Fang, 2009),

analyses have often lacked an examination of the combination of economic, demographic, and,

particularly, policy factors that may play significant roles in influencing household consumption.

As the Chinese government’s decision to officially endorse transitioning to a consumption-led

growth path occurred relatively recently, in 2004, it has not yet been possible to examine the

effects of the transition. This study commences at a time when the first steps towards this new

growth path have been taken and the effects can now be examined, at least preliminarily.

Sharon Riley - Master Thesis – Lund University School of Economics and Management

Page 9 of 58

4 China’s Economic Growth; Pre-reform to present

Consumption in the Chinese economy lagged behind those of western nations for decades after

the Second World War, leaving many with the impression that is was chronically embattled with

challenges that would hinder its ability to ever become a major economic player. In addition, per

capita GDP growth was particularly underwhelming and when the growth of the macro-economy

took off, per capita wealth increases remained lackluster. Economic reforms began in China in

the late 1970s and the country has achieved an almost unprecedented growth rate, an average of

ten percent per year, ever since (Wu, 2000). The growth pattern that was embraced throughout

the 1980s and 1990s was one that was heavily reliant on the ability of the country to attract

foreign direct investment (FDI), peaking in the mid 1990s, and the industrial policy initiatives put

into place by the government through state-owned enterprises (SOEs), often focused on heavy

industrialization and capital deepening projects (Lo, 2006). Also a major focus of Chinese

industrial policy throughout the transformation process was exports: the share of exports of

GDP increased from a negligible amount in the 1960s to nearly thirty percent in 2003, an

unprecedented rate of increase when compared to the other nations of the world (Rodrik, 2006).

As it slowly underwent a process of opening up to foreign investors, China began to attract

unparalleled levels of FDI in the 1990s; ten percent of global FDI was directed towards China by

2003 (Zhang, 2005). It is important to note that China’s openness to foreign investment has not

been without its caveats; many investors were required to form joint ventures with domestic

firms, technology sharing was often required, and protection of the domestic market has been a

priority (Rodrik, 2006). This has enabled unprecedented strengthening of domestic players, as

protectionist industrial policy measures may have enabled domestic firms to leapfrog foreign

competitors, especially in terms of the increasing Chinese activity in the area of high-tech

products. However, it is not only inward FDI that has made China a focus of international

attention: in more recent years, China’s outward FDI flows have also increased substantially,

aimed at 160 countries and increasing ten-fold between the 1980s and 2003 (Zhang, 2005),

suggesting that China’s intentions to become a dominant player in the global economy are

coming to fruition, and in unprecedented ways.

It has been the view, of many economists and policymakers alike, that China’s economic

transformation has been atypical, a special ‘China case’ made possible beginning with market

supplanting policies by a centralized government and slowly transitioning to market fostering

Sharon Riley - Master Thesis – Lund University School of Economics and Management

Page 10 of 58

policies, particularly with ascension to the World Trade Organization in 2001 (Lo, 2006; Wang &

Thomas, 1993). China’s transition began with a unique set of characteristics, largely defined by its

large surplus of agricultural labour (and the low wage demands of these workers) and dictated

mainly by the central planning of the government (influenced largely by five year plans beginning

in 1953) in both the pre-reform period and continuing into the transformation period (Cai F. ,

2008). Regardless of this atypical growth path followed by China, eschewed by other major

economies, China has been able to rise to be an important force on the world stage.

China’s successful emergence as a dominant player in the world economy has not been without

its tribulations. China’s heavy industrialization process aimed at capital deepening has involved an

intensive use of energy and raw materials, heading down a growth path which may not be

sustainable in the long run and requires vast leaps forward in terms of increasing efficiency of

resource use. Adding to the difficulties with this capital deepening growth trajectory are the issues

surrounding the necessity for capital-scarce China to rely heavily on a regulated financial sector in

order to grow; continuing on this growth path inhibits the ability of the country to transition to a

market-oriented financial industry (Lo, 2006), which is becoming increasingly important to

trading partners in the world economy. In addition, China’s transition from a centrally planned

state to a more market-oriented economy required that China change its historical, pre-reform

policy of ‘cradle to the grave’ security for its citizens (Hughes, 2002) and move to a so-called

breaking of the ‘iron rice bowl’ (Chamon & Prasad, 2008) which saw decreased priority in

government spending on expenditures for social programs, most notably in health, education,

and social programs. These factors together, capital deepening and decreased social spending,

lead to an economy for which growth is based on aggregated investment and household saving

rather than domestic consumption.

China’s government has acknowledged that the possibility of long term efficiency of a growth

trajectory relying on capital is limited (Lo, 2006). In addition, the top political and economic

leadership in China has been acutely aware of the heavy reliance on exports and investment for

growth in recent decades. Recognition that China’s trade surplus has continued to grow at a

remarkable rate, setting a global record in 2006, combined with a continued decrease in the

proportion of GDP accounted for by private consumption through 2009 (Bergsten et al., 2009, p.

106) has led the leadership to suggest an alternative growth strategy with the hope of reversing,

or at the very least, slowing, these trends. An adherence to a shift in growth policy from 2004 is

evident in the 2011 Report on the Work of Government delivered by premier Wen Jiabao at the fourth

Sharon Riley - Master Thesis – Lund University School of Economics and Management

Page 11 of 58

session of the eleventh National People’s Congress, which states, “Expanding domestic demand

is a long-term strategic principle and basic standpoint of China's economic development as well

as a fundamental means and an internal requirement for promoting balanced economic

development.” The Chinese government can promote domestic consumption in order to achieve

these long term goals through fiscal, financial, exchange rate, and price policies (Bergsten et al.,

2009, p.116). Wen Jiabao also stated in his 2011 Report on the Work of the Government numerous

promises to the people of China regarding how domestic demand would be expanded. He

specifically addresses increasing government spending that is aimed at boosting consumer

demand, increasing subsidies to rural residents and low-income urban residents (including

subsidies for rural residents to purchase home appliances), and strengthening infrastructure,

among many others (Jiabao, 2011).

China’s economy is seemingly headed down a markedly different growth path from the one that

brought about economic transformation over the past few decades; most notable here is the

increasing importance of domestic consumption as a driver of economic change and growth.

With a burgeoning population and increasing wages, policy makers in China have seemingly

recognized the potential to harness increasing household consumption as a driver of economic

growth, though to date its contribution to GDP has not increased.

5 Theories of Household Consumption

Chinese leadership and scholars agree that consumption expenditure contribution to GDP in

China is lagging behind other world economic powers (Fang, 2009; Lardy, 2006; Bergsten,

Freeman, Lardy, & Mitchell, 2009). The theories explaining this perceived lackluster contribution

can be categorized into three primary groups. The first theory relates to the growing income gap

between rural and urban households (as well as between coastal and inland households) in China.

It is hypothesized that the inability of middle and lower income groups to raise consumption

levels at a rate consistent with the ever expanding economy has led to inadequate consumption

demand (Fang, 2009; Yongbing, 2005). Income inequality is no small problem in China with the

income gap widening drastically (Yao, Zhang, & Feng, 2005); the income gap between rural and

urban areas has been debated, but it has been suggested that it has been increasing since 1995,

with the absolute incomes of the lowest income brackets have been decreasing (Benjamin,

Brandt, & Giles, 2004). Income inequality certainly has the potential to influence average per

Sharon Riley - Master Thesis – Lund University School of Economics and Management

Page 12 of 58

capita household consumption, as overall growth may be reflective of increases in income and

wellbeing enjoyed by only those at the high-end of wage earners. Thus, the majority of lowerincome workers may be tied to continued low consumption paths.

The suggestion that Chinese consumers are inherently prone to saving, that they are not lavish

consumers by tradition is offered as an alternative theory to explain relatively low levels of private

consumption. The reluctance of Chinese consumers to spend has been suggested to be linked to

a

tradition of Confucianism

which values thrift and modest economic comfort

(Watchravesringkan, 2007). In addition to a propensity for saving, the use and popularity of

consumer credit in China is lower than that observed in other countries, even in neighbouring

Asian countries with a comparable development status, further contributing to lower levels of

private consumption (Woetzel et al. 2009). Furthermore, though cultural norms and values

rooted in Confucianism may be changing, it has been suggested that changes in consumption

patterns lag behind, as habit formation may play a significant role in determining saving and may

explain continued propensity towards saving (Carroll & Weil, 1994). Growth in the savings rate

has, quite obviously, an inverse effect on household consumption.

The third theory offered as an explanation for inadequate consumption is also related to the

savings rate, but places more emphasis on the role of the state, positing that the weak welfare

system in China leads consumers to save for their futures, preparing for calamities for which the

state would not provide assistance. Government spending on healthcare, pensions, welfare, and

education has been found to have a large impact on household consumption (Baldacci, et al.,

2010); thus the criticism that China’s social programs are relatively weak may offer some

explanation of observed low consumption levels. This is of particular interest in this study, as

government expenditure on social programs is a means which has been suggested for utilization

by the Chinese government in order to attempt to induce transition to a consumption-driven

growth path. This third theory is also related to theories positing that income inequality leads to

decreased growth in household consumption, as the government possesses the ability to increase

income of the lowest wage earners by providing other social programs, such as housing subsidies

in rural areas, and thereby household consumption. A previous analysis into past rural housing

subsidy programs revealed a significant correlation with growth of household consumption

(Fang, 2009). It is logical to posit that the breaking of the ‘iron rice bowl’ which induced

Sharon Riley - Master Thesis – Lund University School of Economics and Management

Page 13 of 58

precautionary savings in weary Chinese consumers (Chamon & Prasad, 2008) must be related to

lackluster growth in consumption, as precautionary spending increased as a result.

The savings rate in China is theorized to play a crucial role in determining how factors influence

household consumption. Previous studies have looked into the role of the Life Cycle Hypothesis in

determining savings rates in China (Modigliani & Cao, 2004; Chao, LaFarrgue, & Yu, 2011).

These analyses are of interest here, as it is expected that factors which positively affect savings

will have an opposite and direct effect on consumption. The Life Cycle Hypothesis as applied by

Modiglianai and Cao (2004) suggests that savings increase during the middle and end of wage

earning years, and decrease again during retirement; leading to suggestions that, as income has

increased since the current retired group last exhibited high savings, the savings ratio computed

overall has increased (Chao, LaFarrgue, & Yu, 2011). Additionally, the one child policy is

expected to increase saving, thereby reducing consumption, as parents know that they will have

only one income to rely on for support when they retire in the future.

Part one of this thesis will seek to look at a more detailed picture of the rise in household

consumption; specifically through examining aggregate purchasing trends for important durable

goods and household commodities. It is expected that demand for these goods has been

increasing over the past three decades, as wages increased. However, as has been discussed, is it

the proportion of income that is spent on consumption that has been falling, such that, even as

income and purchases increase, the savings rate has been increasing faster; theories explaining

this have been described above. It is pertinent now to examine whether absolute levels of

consumption for basic goods have been increasing, which is completed in the following section.

6 Part I - Exploratory Study of Consumption of Household

Goods

This chapter contains findings in the exploration of trends in household consumption patterns.

This component of this study will serve as an exploratory study into the changing nature of

Chinese consumption of common household commodities and major foodstuffs. This will serve

to establish two objectives: how are levels of household consumption changing (what is the

domestic demand?) and where do goods consumed by households originate – in China or

Sharon Riley - Master Thesis – Lund University School of Economics and Management

Page 14 of 58

abroad? (is the domestic market able to meet domestic demand?) It is not possible with the

available data to trace country of origin of foreign produced goods, but an effort will be made to

establish whether or not they are produced domestically.

6.1

Data

Data has been gathered primarily from China’s Statistical yearbooks. It has been collected to

form two data sets.

6.1.1

Household Commodities

Four durable household commodities have been selected to focus analysis upon; television sets,

bicycles, electric fans, and cameras. These goods have been selected based on the assumption that

they are (1) end products, and will not go on to be processed into a more advanced commodity1

(like fabric and textiles, for example), (2) they are most likely to be consumed by households,

rather than firms (office equipment and computers for example may be more likely to be

consumed by firms than households), and (3) data is available in these specific categories.

Although it would have also been beneficial to analyse trends in other popular consumer goods

which are likely to purchased as perceptions of personal wealth increase – specifically clothing

and textiles, personal electronics, and computer related equipment - the data simply is not

available in a form where it is disaggregated to a level which could be consistently compared

across different statistical categories. These four commodities, particularly television sets and

bicycles are rather unambiguous in their interpretation, although the eventual separation of

colour and black and white television sets in the data could pose a concern. Cameras pose more

of an issue, especially as digital cameras are introduced in recent years and may have

categorical/labeling changes.

Data on the four selected commodities is available for:

Output of Major Industrial Products (in units)

Major Export Commodities in Volume and Value (units and US dollars)

A high share of china’s imports are imports for processing – 35 percent of all imports in the early 1990s

to 50 percent by 1997 (Rumbaugh & Blancher, 2004)

1

Sharon Riley - Master Thesis – Lund University School of Economics and Management

Page 15 of 58

Number of Major Durable Consumer Goods Owned per 100 Urban Households at Year

End (units)

Number of Major Durable Consumer Goods Owned per 100 Rural Households at Year

End (units)

Data on television sets only is available for:

Major Import Commodities in Volume and Value (units and US dollars)

Data has been collected primarily from China Statistical Yearbooks. Unfortunately, yearbooks

are only available in English back to 1997 (which contains data from 1996, as well as detailed

historical data, as far back at 1952 in some cases), and several years are not available – 1998, 2000,

2001, 2004, 2006, and 20072. Data for household commodities has been collected from the

Industry, People’s Livelihood and Worker’s Wage, and Domestic Trade, Foreign Trade and Economic

Cooperation sections of the China Statistical Yearbook.

6.1.2

Food Commodities

Data has been gathered on major foodstuff commodities purchases by households in both rural

and urban areas. In these instances, complete data sets are available for sugar and edible vegetable

oil, with limited data available for grains, aquatic products, and liquor which was not sufficient to

present in this thesis. This data is obtained from annual reports on the annual consumption of

households in the People’s Livelihood and Workers’ Wage section of the China Statistical Yearbook.

Sugar and edible vegetable oil will be focused on in this study. These goods are of interest, as,

although the demand for them is not likely to expand indefinitely with increasing wealth, it is

likely to increase as households surpass the poverty line and can afford to purchase these

ingredients in sufficient quantities to fulfill dietary requirements or desires.

2

Not available from the Asia Library at Lund University

Sharon Riley - Master Thesis – Lund University School of Economics and Management

Page 16 of 58

6.2

Limitations of Data

Limitations involved with this use of China’s statistical administrative records are, unfortunately,

many. The data series used in this study were constructed from various issues and sections of the

China Statistical Yearbook; when combining data in this manner, one cannot be absolutely sure

that the categories of goods are consistent across data sets. For example, the category ”cameras”

may be more or less inclusive in the customs data used for import and export quantities than it is

in data on industrial output3.

An example of data which is not useable, but for which much data is available, is “electronics,”

which creates ambiguity in interpretation, and may refer to parts imported to then be further

manufactured into goods. As China’s trade deals heavily in the import of raw materials and the

export of components, it is occasionally ambiguous whether or not goods reported in the data are

actually finished products ready for sale to the consumer. Differing definitions and stages of

production pose a problem in this study, which is the reasoning for choosing products that are as

simple and unambiguous as possible.

This study may be said to be limited in its inability to examine trends over a long time period.

Much of the data on consumer goods does not date back further than the 1990s, giving a limited

data set, though this can be argued to be sufficient for the scope of this study, which seeks to

examine trends during the economic transformation.

Further limitations exist in the quality of the data collection by the statistical agency itself. In

some cases, it appears that the number of exports reported exceed the amount produced for a

given year, which may indicate errors in data collection, or may perhaps be an accurate

representation, as firms may hold goods produced in one year and wait to export them in

subsequent years. This has posed large complications in establishing domestic consumption, as it

yields negative results. Despite attempts to smooth data (described in section 6.3.1), exports still

exceeded output in many cases, leading to the conclusion that the problem is likely not time lags

within firms but, rather, due to differences existing internally within China’s statistical data

collection departments for these two different data sets. The data series constructed on domestic

The source for data on industrial output is not specified in the yearbooks and is presumably reported by

manufacturers or estimated by the statistical agency.

3

Sharon Riley - Master Thesis – Lund University School of Economics and Management

Page 17 of 58

output of goods was created using data on industrial output; details on the manner in which this

data was collected is not seemingly available and it may be assumed that it is voluntarily or selfreported, leading to possible faults and misrepresentations within the data itself. Criticisms of the

quality of the data found in the China Statistical Yearbooks are many, with researchers calculating

discrepancies in not only growth statistics, but also in consumption figures as well. For example,

it has been suggested that the data available on household outlays for consumptive purchases do

not agree with national data for retail sales, suggesting that data on household consumption may

be false or simply an incorrect estimate (Rawski, 2001). However, despite inherent flaws, this data

is the best and only available within the budget of this masters thesis.

With regard to food commodities, it is important to note that the demand calculated based on

per capita consumption of sugar and edible vegetable oil reflects only household consumption.

Direct consumption by households was estimated to make up approximately fifty percent of the

total sugar consumption in the 1990s (United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, 1997),

with the remainder being utilized in industrial processing of food products. Thus, this study will

not capture aggregate domestic demand, but aggregate household demand.

It is also important to note that data is not available across consistent time periods, which

occasionally makes for confusing comparisons. An attempt has been made to display data over

the same or similar time periods as much as possible.

6.3

6.3.1

Methods

Household Commodities – durable goods

Data on consumption of domestically produced goods that are consumed within China is not

explicitly available4 and will be established, based on the following.

Domestic Consumption of good (x) in year (1) = Output (x1) – Exports (x1)

4

Where available, import data has been collected.

Sharon Riley - Master Thesis – Lund University School of Economics and Management

Page 18 of 58

Data series for output, exports, and imports (where available) have been constructed by piecing

together yearly reported statistics within the China Statistical Yearbook. Data on exports and

imports is reported only for major export commodities; therefore, some commodities appear and

disappear as their importance changes and they no longer appear in the list of top commodities.

In cases where data is unavailable for specific years (or where yearbooks are unavailable), linear

interpolations have been utilized. In some situations, when data is not available at the beginning

of the series, linear extrapolation has been used, for a maximum of four years, to avoid distortion

of actual trends. As the available data displays irregular trends that occasionally lead to negative

figures for domestic consumption, a five year moving average has been applied in an attempt to

smooth the data as well as to account for the problem of exports exceeding production in some

years (due to time lags or otherwise).

In addition, data is available on the number of durable consumer goods (specifically including

colour television sets, electric fans, cameras, and bicycles) owned per one hundred rural and per

one hundred urban households. This data is not complete, but linear extrapolations have been

utilized to fill in missing data within the series. This data is used to examine trends in the

popularity of household durable goods.

As these are durable goods, it is possible to assume that the increase from one year to the next in

the number of durable goods present per one hundred households represents the actual demand

for new products. This may be particularly true in rural households, as it is possible that many of

these goods were purchased for the first time in the past decade and have not needed

replacement. However, it must be acknowledged that, while new items may be purchased and this

will be captured in the data, some items may also be replaced (these goods are hereby referred to

as replacement goods), which would not be captured in the number of goods present in

households. However, as, particularly in rural households, it is possible that many of these goods

were purchased for the first time in the past decade. This will be further explored. In any case,

trends in the four study commodities’ popularity in Chinese households will be established using:

(𝑥𝑡 − 𝑥𝑡−1 )⁄

100) ∗ (𝑃𝑜𝑝) } + 𝑅𝑒𝑝𝑙𝑎𝑐𝑒𝑑 𝑥

𝐼𝑛𝑐𝑟𝑒𝑎𝑠𝑒 𝑖𝑛 𝑑𝑒𝑚𝑎𝑛𝑑 𝑓𝑜𝑟 𝑔𝑜𝑜𝑑𝑥 = {(

𝑡−1

ℎ𝑜𝑢𝑠𝑒ℎ𝑜𝑙𝑑 𝑠𝑖𝑧𝑒

Where Replaced xt-1 represents replacement goods; the number of goods that were removed from

households in year t-1 and subsequently replaced with new goods.

Sharon Riley - Master Thesis – Lund University School of Economics and Management

Page 19 of 58

If the number of replacement goods not captured in the data is assumed to be zero, this data can

be used to establish yearly demand for each of the four commodities (even without this

assumption, this figure can be used as an approximation of minimum demand). This data on

household demand for the four study goods can be compared to the number of the goods that

are produced in China (available from data on industrial output) but not exported (output minus

exports), as well as with import data (only available for television sets).

6.3.2

Food Commodities

Data series on two major food commodities were constructed using available data on per capita

consumption in urban and rural areas. All data was transformed into tons5 to maintain

consistency across measures (some data is reported in yearbooks in kilograms, others in tons,

such as exports).

The per capita household demand for both sugar and edible vegetable oil has been transformed

into a measure of aggregate household consumption of these goods, which can, in turn, be

compared with total domestic output, as well as imports and exports.

The per capita consumption was applied to the entire urban and rural population across the time

period, to get an approximation of aggregate household demand.

An approximation of annual urban per capita consumption of sugar in units is unavailable and

was created from the data available on per capita annual expenditure on sugar. The unit price was

estimated from an average of calculated import and export unit prices6 and the total expenditure

divided by this unit price to obtain an approximation of per capita demand. This estimated series

for per capita consumption of sugar was compared with an estimate of the average sugar

consumption provided by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (1997)7 to

ensure accuracy.

1 kilogram = 0.001102 US short tones

Derived from data on import and export volumes and values

7 The FAO estimated sugar consumption to be approximated 5.9 kilograms(0,005 tons) in 1995/1996

overall; the method described here yielded an estimate in the order of 9 kilograms (0,01 tons) for urban

consumption, which when averaged with the much lower per capita rural consumption gives an

approximate demand of 6.3 kilograms (0,007 tons), very close to the FAO estimate. A weighted proportion

5

6

Sharon Riley - Master Thesis – Lund University School of Economics and Management

Page 20 of 58

In addition, data series were constructed on output, exports, and imports, using yearly reports on

major food commodities. This data was used to establish domestic demand for domestically

produced goods, in the same manner as it was for household commodities.

6.4

Results

The results of the exploratory examination of data available on what households consume, from

where, and in what numbers are presented in this section. Where data does not yield interesting

results, it is presented and explained in the appendix.

6.4.1

Colour Televisions

The data for colour televisions is the most interesting of the four household commodities

examined. Not only is its existence consistent over the longest time period, but it is also the most

complete, as data for imports is available. Data for black and white televisions is also available

(through the number of durable goods in households statistics), but it ceases to exist for urban

areas in the 1990s and is indicative of declining trends in the prevalence of black and white

televisions of households. This data is not utilized here, as one objective of examining statistics

on the number of televisions present per 100 households, in both rural and urban areas, is to look

at the demand for new products, not to look at the slow phasing out of old, redundant

commodities. As has been discussed, it is assumed that most colour televisions purchased during

the 1980s and 1990s were the first colour televisions to be purchased for the household, and not

replacing existing old televisions. As is expected, the number of colour televisions per 100

households has increased substantially over the past two decades (see Figure 6-1), increasing

almost seven times in urban areas, and catapulting from near non-existence in rural areas to an

average of close to one television per household. This is expected, as household income

increased over this period as well, and colour televisions quickly went from a luxury item

afforded only by the very wealthy to a prominent household item.

would yield almost identical estimates. The world average annual per capita consumption is 20 kilograms

(0,22 tons).

Sharon Riley - Master Thesis – Lund University School of Economics and Management

Page 21 of 58

The estimated yearly total demand for televisions has begun to decline in urban areas (see Figure

6-2) reaching its peak in approximately the year 2000. The demand continues to remain steady in

rural areas, which is expected as households in rural areas are expected to be generally behind in

the take-up of such goods. It is important to note that while Figure 6-2 suggests higher total

demand for colour televisions in rural areas, this is a function of a larger portion of the

population living in rural areas and not of a higher per capita demand. Per capita demand is

better approximated by examining the trends in demand8 per 100 households (Figure 6-3), where

one can see the point at which the amount by rural demand increases supersedes the amount that

urban demand increases. After this point it can be assumed that, while not satiated, the year to

year increase in demand in urban areas for colour televisions has begun to decline as the initial

rush to acquire the first television is over. This is still occurring in rural areas, though one can see

that it too is beginning to reach a plateau.

160

140

120

100

80

Rural Households

60

Urban Household

40

20

0

Figure 6-1 - Number of Colour televisions owned per 100 households at year end, 1985-2008

Demand here means the amount of new televisions that would have been bought from one year to the

next, not taking into account replacement goods.

8

Sharon Riley - Master Thesis – Lund University School of Economics and Management

Page 22 of 58

1600

1400

1200

1000

Rural

800

Urban

600

400

200

0

1995

1998

2001

2004

Figure 6-2 – Minimum estimated total yearly demand for colour televisions (10 000 televisions) in China, 1995 – 2005

(five year moving average)

10

9

8

7

6

5

Rural

4

Urban

3

2

1

0

1988

1991

1994

1997

2000

2003

Figure 6-3- Annual unit change (colour televisions) per one hundred households, 1985-2005 (five year moving averages)

An estimate of the aggregate demand for televisions is obtained by summing the rural and urban

total demand for new televisions, the results for which are given in Table 6-1. It is interesting to

note that this estimate is relatively close in its approximation of domestic demand to the

approximations yielded from statistics on domestic output and exports (plus imports). The

approximations for household demand from the former method are lower than those of the

latter until 2003. As the amount reported by the former method (establishing demand from an

Sharon Riley - Master Thesis – Lund University School of Economics and Management

Page 23 of 58

increase in prevalence of colour televisions per one hundred households) is a minimum estimate9,

it would be expected that this estimate would be lower in all cases. However, this discrepancy

may be explained by lags in the data: televisions that are produced in year(x) may not be

purchased until subsequent years, leading to a deflated or inflated approximation of domestic

consumption in that year. It is also, again, pertinent to note that the way in which data on

domestic output is measured is not clear and may not be an accurate representation of reality.

Both approximations of domestic consumption demonstrate the same trend, of increasing to a

plateau in the early 2000s and declining thereafter.

Table 6-1 - Summary of Data on Estimated Consumption of Colour Televisions in China, 1997 - 2006

Year

Output

(10 000

televisions)

Exports

Imports

Domestic

Consumption10

Household

Consumption11

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

3166,94

3506,267

3942,5

4580,85

5219,483

5889,687

6629,587

7360,305

8006,652

8299,702

1015,5

1240,2

1490,9

1942,7

2691,1

3657,7

4853,3

6338,6

6726,2

6801,4

50,5

29,3

22,7

17,5

31,5

43,6

63,9

90,5

111,3

103,9

2151,44

2266,067

2451,6

2638,15

2528,383

2231,987

1776,287

1021,705

1280,452

1498,302

1643,45

1896,848

1952,594

2037,49

2128,654

2052,684

1997,739

1897,23

1668,207

-

6.4.2

Bicycles

The data available for household consumption of bicycles is not as comprehensive in scope as

the data for televisions – noticeably as there is no data for imports of bicycles available (though it

is arguable that this amount may be negligible). The number of bicycles present per one hundred

households (see Figure 6-4) shows a trend of initial increase and eventual decline, likely indicative

of the increasing prevalence of motor vehicles, with car prevalence doubling in China in only two

It is a minimum estimate amount because it only takes into account the increase in the prevalence of

televisions, not the replacement of old televisions. Also, it includes no estimation of televisions purchased

for other purposes, i.e. for business use.

10 As estimated by subtracting exports from domestic output

11 As estimated by the increase in prevalence of colour televisions from one year to the next per 100

households

9

Sharon Riley - Master Thesis – Lund University School of Economics and Management

Page 24 of 58

years from 2003 to 2005 (Brown, 2005); this trend is observed first in urban areas and followed

by rural areas. The estimated yearly aggregate demand for bicycles has been declining since the

start of this study period (Figure 6-5)12, suggesting that bicycles have been being slowly phased out

and replaced by motorbikes and cars in many households (as is expected, this trend is first

observed in urban areas). Even in the mid 1980s, the amount by which the prevalence of bicycles

per one hundred households in both urban and rural areas grew declined (Figure 6-6)13, and in the

mid 1990s the absolute level of bicycles per one hundred also began to decline (suggesting that

no new bicycles were being purchased) and thus rendering it impossible to calculate domestic

consumption of bicycles from this data after 1995.

The trends displayed in data for bicycles is less reliable than that for televisions, as it can be

assumed that the prevalence of used bicycles in the market is much higher (as bicycles have been

available and common for much longer than households). This makes the increase (or decrease)

in the number of bicycles present per one hundred households less reflective of any real trends in

consumption, as old bicycles may be being replaced (which would not be captured in the year to

year increase) or, alternatively, an increase in the absolute number of bicycles may reflect

purchase of used bicycles rather that new ones14.

Note that rural aggregate demand for new bicycles is also a function of a higher rural population

When the amount by which the number of bicycles per one hundred households increases becomes

negative, it is then implied that ‘demand’ (not including replacement goods) is zero. The negative figures

are included in Figure 6-6 to give an idea of the amount by which the number of bicycles per one hundred

households is declining.

14 This latter effect may result be true of a transfer of bicycles from higher income urban areas to lower

income rural areas, though there is no evidence of such a transfer. Otherwise, it would likely not affect

results, as one used bicycle would simply be transferred from one household to another and not change

trends.

12

13

Sharon Riley - Master Thesis – Lund University School of Economics and Management

Page 25 of 58

250

200

150

Rural

100

Urban

50

2006

2005

2004

2003

2002

2001

2000

1999

1998

1997

1996

1995

1994

1993

1992

1991

1990

1989

1988

1987

0

Figure 6-4 - Number of Bicycles owned per 100 households at year end, 1985-2006 (five year moving average)

1400

1200

1000

800

Rural

600

Urban

400

200

1988

1989

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

0

Figure 6-5 - Minimum estimated total yearly demand for new bicycles (10 000 bicycles) in China, 1988 – 2007 (five year

moving average)

Sharon Riley - Master Thesis – Lund University School of Economics and Management

Page 26 of 58

10

8

6

4

2

Rural

-2

1988

1989

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

0

Urban

-4

-6

-8

-10

Figure 6-6 - Annual unit change (bicycles) per one hundred households, 1985-2006 (five year moving averages)

Further data on domestic demand and exports for bicycles in available in the appendix (see section 10.1.1)

6.4.3

Cameras

The data available to indicate the prevalence of cameras in households indicates a marked and

nearly linear increase in the number of cameras per one hundred urban households to 2004 (at

which point the level peaks and begins to unexpectedly decline), while the prevalence of cameras

in rural households is negligible and remains so (Figure 6-7). The calculated approximation of the

minimum number of new cameras purchased15 is erratic at best (see Figure 6-8). This is explained

by the fluctuating year to year increases in cameras per one hundred households (smoothed over

in Figure 6-7) by applying five year moving averages). This data is further complicated by the

possible confusion of data in the yearbooks, as digital cameras are eventually separated from

cameras, though it is not clear in the data when cameras refers to all cameras or only to film

cameras. This may explain the otherwise unexpected decline in the year to year increase in

cameras per one hundred households observed in Figure 6-9.

Calculated based on the increase in number of cameras per hundred households and translated into the

number of new cameras calculated by the entire urban population

15

Sharon Riley - Master Thesis – Lund University School of Economics and Management

Page 27 of 58

50

45

40

35

30

25

Rural

20

Urban

15

10

5

2006

2005

2004

2003

2002

2001

2000

1999

1998

1997

1996

1995

1994

1993

1992

1991

1990

1989

1988

1987

0

Figure 6-7 Number of Cameras owned per 100 households at year end, 1987-2006 (five year moving average)

350

300

250

200

Rural

150

Urban

100

50

1988

1989

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

0

Figure 6-8 Minimum estimated total yearly demand for new cameras (10 000 cameras) in China, 1988 – 2007 (five year

moving average)

Sharon Riley - Master Thesis – Lund University School of Economics and Management

Page 28 of 58

3

2.5

2

1.5

1

Rural

0.5

0

1988

1989

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

-0.5

Urban

-1

-1.5

-2

-2.5

Figure 6-9 Annual unit change (cameras) per one hundred households, 1985-2006 (five year moving averages)

Further data on domestic demand for camera can be found in the appendix (see section 6.3.2)

6.4.4

Electric Fans

Finally, data on electric fans shows a continual increase through the 1990s and 2000s in the

number of electric fans per 100 households in both rural and urban areas, with the number of

electric fans dropping very slightly in urban areas in 2004 before data is no longer available (for

urban areas only). The rate of increase is observed to be higher in rural areas, as is shown in

Figure 6-10. Although the levels are increasing, the amount by which these levels are increasing is

diminishing, leading to a diminished aggregate demand (not including the demand for

replacement goods, which is surely substantial as old fans no longer operate and residents can

afford to upgrade), as shown in Figure 6-11. Figure 6-12 shows us that the amount by which the

number of fans present per one hundred households is increasing accelerated in urban areas at

the outset of the period, but is now diminishing in both rural and urban areas. This is possibly

indicative of an early ‘rush’ to buy electric fans in rural areas as disposable incomes allowed for

this former luxury good.

Sharon Riley - Master Thesis – Lund University School of Economics and Management

Page 29 of 58

200

180

160

140

120

100

Rural

80

Urban

60

40

20

2006

2005

2004

2003

2002

2001

2000

1999

1998

1997

1996

1995

1994

1993

1992

1991

1990

1989

1988

1987

0

Figure 6-10 Number of electric fans owned per 100 households at year end, 1987-2006 (five year moving average)

2000

1800

1600

1400

1200

1000

Rural

800

Urban

600

400

200

1988

1989

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

0

Figure 6-11 Minimum estimated total yearly demand for new electric fans (10 000 cameras) in China, 1988 – 2007 (five

year moving average)

Sharon Riley - Master Thesis – Lund University School of Economics and Management

Page 30 of 58

14

12

10

8

6

Rural

4

Urban

2

-2

1988

1989

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

0

-4

Figure 6-12 Annual unit change (electric fans) per one hundred households, 1985-2006 (five year moving averages)

6.4.5

Comments

These results demonstrate the expected trends in Chinese household consumption. Goods that

were perceived as luxury goods when incomes were considerably lower, in the 1980s and 1990s,

have been increasing in popularity. Of note is the peak in per capita demand for new products,

such as televisions (not including replacement goods), as the product is diffused throughout

society and prevalence is close to at least one per household. The opposite trend is present in

commodities that have since been upgraded; the decrease in per capita demand is clear and

marked. It is logical to conclude from this exploration of trends in major household commodities

that the same effects may be visible in other products as well; new technologies and products are

first largely diffused throughout urban society, where wages are higher, to a peak. A similar

diffusion occurs in rural areas, though following a lag in time and the good may never become as

prevalent as it is in urban areas if it is a more high-tech luxury good.

Of interest, then, is to also examine trends in major foodstuffs, a portion of consumption

spending that is significant and ubiquitous amongst all households, rural or urban.

Sharon Riley - Master Thesis – Lund University School of Economics and Management

Page 31 of 58

6.5

6.5.1

Food Commodities

Sugar

Per capita consumption of sugar in rural areas remained relatively low across the period (see

Figure 6-13), even declining minimally. Urban consumption of sugar, however, began to increase

in the early 2000s, which may be a factor of simultaneous increases in urban wages, or reflective

of lifestyle changes, as increasing westernization in urban areas may decrease the prevalence of

traditional eating habits, which do not include heavy sugar consumption (United Nations Food

and Agriculture Organization, 1997). Certainly, per capita sugar consumption in China has a long

way to go before it reaches even the world average of twenty kilograms (0.022 tons) per year in

1996 or the EU average of forty kilograms (0.044 tons) per year, as of 2004 (World Health

Organization, 2011). It remains to be seen if increasing household income or the prevalence of

western values will increase per capita consumption in China to these levels.

0.02

0.018

0.016

0.014

Per capita

consumption of sugar

in rural areas, tons

0.012

0.01

0.008

Per capita

consumption of sugar

in urban areas, tons

0.006

0.004

0.002

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

0

Figure 6-13 per Capita Consumption of Sugar in Rural and Urban Areas, 1995-2008

It is also of interest to examine whether China is producing its own sugar or obtaining it from

elsewhere. Sugar imports have declined by 74% since data is first available in 1995 (see Table 6-2),

while total aggregate consumption has increased almost ten-fold over the same period, though

this is due almost entirely due to an increase in urban population and not necessarily due to the

increase in per capita consumption. Domestic production is higher than domestic consumption

in nearly all years, with the exception of 2001, 2005, and 2006, when it is marginally lower and it

Sharon Riley - Master Thesis – Lund University School of Economics and Management

Page 32 of 58

can be assumed that either imports or reserves made up the deficit in these cases16. It is also

worth noting that exports have also fallen considerably, by 88%, though sugar imports and

exports were never very large compared with domestic production (over this period, 1995-2008).

The sugar case is an example of a sector in which demand is rising, and output has been able to

increase by a sufficient magnitude to meet this demand. It is interesting to note that, in contrast

to household goods, China is actually a net importer of sugar.

Aggregate household consumption estimates reveal relatively similar approximations of demand

as to estimates of domestic consumption, though it is logical that aggregate household estimates

would be lower, as they do not include sugar which is utilized for processing into different food

products.

Table 6-2 Summary of Data on Estimated Consumption of Sugar in China, 1990 - 2008

Year

Output

(10 000 Tons)

Exports

Imports

Domestic

Consumption17

Household

Consumption18

1990

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

582,00

558,64

640,20

702,58

826,00

861,00

700,00

653,10

926,00

1083,94

1033,70

912,37

949,07

1271,38

1449,48

48,00

66,00

38,00

46,00

43,50

41,00

20,00

33,00

10,32

8,52

11,98

15,44

11,05

5,84

295,00

125,00

78,00

51,00

57,50

64,00

120,00

118,00

78,00

121,00

128,00

135,00

119,00

78

510,64

574,20

664,58

780,00

817,50

659,00

633,10

893,00

1073,62

1025,18

900,39

933,63

1260,33

1443,64

139,09

119,82

580,40

587,50

593,20

660,34

690,06

739,21

746,83

783,60

859,85

947,66

1028,05

1116,21

1178,85

6.5.2

Edible Vegetable Oil

Also, it must be noted that data was not available for 2005 and this figure is a linear interpolation

As estimated by subtracting exports from domestic output

18 As estimated by the per capita demand for sugar in rural and urban households applied to entire

population

16

17

Sharon Riley - Master Thesis – Lund University School of Economics and Management

Page 33 of 58

Per capita consumption of edible vegetable oils shows a gradual increase in both urban and rural

areas (see Figure 6-14). Like the sugar case, it is unlikely that these rates will continue to rise

indefinitely. However, increasing westernization of food, particularly in urban areas may lead to a

sustained increase in the consumption of edible vegetable oil in the short run.

0.012

0.01

Per capita

consumption of edible

vegetable oil in rural

areas, tons

0.008

0.006

Per capita

consumption of edible

vegetable oil in urban

areas, tons

0.004

0.002

1990

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

0

Figure 6-14 per Capita Consumption of Edible Vegetable Oil in Rural and Urban Areas, 1995-2008

Edible vegetable oil represents a slightly different example, as domestic consumption has not

risen nearly as quickly as for sugar, only doubling over the period (see Table 6-3). However,

during this period, domestic output also doubled and imports grew by nearly 285%, while exports

remained low, hovering at or below one percent of total output since 2003 (data is not available

further back in time). Output remained well in excess of domestic consumption, except for

between 1998 and 2000. It is very likely that the types of oil exported varies greatly from the

types imported, as palm oil is an extremely important commodity in food preparation and China

is the world leader is palm oil imports, but is not a major player in exports (Koh & Wilcove,

2007).

Sharon Riley - Master Thesis – Lund University School of Economics and Management

Page 34 of 58

Table 6-3 Summary of Data on Estimated Consumption of Edible Vegetable Oil in China, 1990 - 2008

Year

Output

(10 000 Tons)

Exports

Imports

Domestic

Consumption19

Household

Consumption20

1990

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

1144,50

946,54

893,73

602,48

718,90

835,32

1383,17

1531,22

1584,29

1235,44

1785,34

2335,23

2636,98

2419,15

5,97

6,52

23,22

39,92

16,63

24,76

213,00

153,00

275,00

206,00

192,50

179,00

165,00

319,00

541,00

676,00

672,50

669,00

838,00

816,00

1578,32

1228,92

1762,11

2295,31

2620,35

2394,39

1134,61

673,45

710,16

745,08

791,45

846,09

898,30

911,08

941,35

980,71

915,30

980,79

980,06

1035,81

1112,68

The trends observed in this section are indicative of an economy undergoing the early stages of

development, transitioning from an agrarian economy in which residents have little disposable

income available to spend even on necessities or durable goods and may struggle to buy even the

basics, to an economy with decreased market control on behalf of the government and rising real

wages. Consumers in the latter situations are actually able to make purchasing decisions for the

first time. No longer restricted by tight market restrictions or limited income, consumers in China

now, for the first time, are able to enter the market for consumer goods not necessary for daily

life. The data presented in this section shows the increase in demand as consumers are able to

afford the necessities as well as those good previously perceived as luxuries.

It could be assumed that these upward trends will continue to increase, as it appears from a basic

appraisal of the situation that consumers will only become more empowered to make purchasing

decisions. However, as has been discussed, growth in consumer spending has not been rising at

rates deemed to be sufficient to sustain long term economic growth, or even at rates similar to

As estimated by subtracting exports from domestic output

As estimated by the per capita demand for edible vegetable oil in rural and urban households applied to

entire population

19

20

Sharon Riley - Master Thesis – Lund University School of Economics and Management

Page 35 of 58

countries at a comparable stage of development. The factors potentially linked to the growth rate

of household consumption will be examined in part two of this thesis.

7 Part II - Explanatory Study: Household Consumption on the

Rise

This chapter will outline the data, methods, and results of the attempt to conduct an explanatory

study into factors influencing levels of household consumption.

7.1

Data

Data was gathered from China Statistical Yearbooks (online and at the library) on the following

variables:

-