ACM Position Statement on the use of Donor Human Milk

advertisement

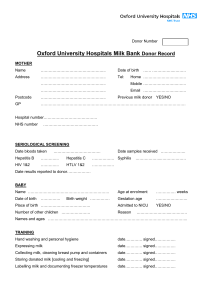

Australian College of Midwives Draft Position Statement on the use of Donor Human Milk Consultation Paper: 17 January 2014 The Australian College of Midwives (ACM) is currently developing a Position Statement on the Use of Donor Human Milk. The Draft provided below has been developed by the Baby Friendly Health Initiative (BFHI) Advisory Committee based on available evidence. To ensure the final endorsed Position Statement is informed by the latest evidence and expertise and reflects professional and regulatory codes, standards and frameworks, we now ask for feedback from members and interested stakeholders on the draft provided below. Unless provided in-confidence, submissions will be published on the ACM website after the public consultation period, to encourage discussion and inform stakeholders and the broader community. Once the consultation period ends, the feedback will be collated to inform a final draft. This will then be reviewed by the BFHI Advisory Committee and submitted for endorsement by the ACM Board. The final Position Statement will then be published on the ACM website (http://www.midwives.org.au). HOW TO SUBMIT Once completed, there are three ways to make your submission; 1. Online survey: https://www.surveymonkey.com/s/8ZZFKH7 2. Email: sarah.stewart@midwives.org.au 3. Post: Sarah Stewart Australian College of Midwives PO Box 965 Civic Square ACT 2608 For those who prefer to email or post their responses, we encourage you to: 1 1. Download the position statement (doc and pdf) and utilise the questions included as a guide for your feedback. 2. Include any additional comments you may have. 3. Include the following as the title for your submission: Consultation – Use of Donor Human Milk. 4. Provide your name, job title and, if representing an organization, the organisation’s details. Unless provided in-confidence, submissions will be published on the ACM website after the public consultation period, to encourage discussion and inform stakeholders and the broader community. There is no need to send a hard copy of your submission if you have submitted it by email. The ACM endeavours to formally acknowledge receipt of submissions within 5 business days. DEADLINE FOR SUBMISSIONS: COB Friday 28th February. Submissions received after this date will not be considered. Any questions about this consultation process may also be directed to Sarah Stewart: Email: sarah.stewart@midwives.org.au Phone: 02 6230 7333 2 ACM Position Statement on the use of Donor Human Milk The ACM supports and encourages parents to exclusively breastfeed their children to six months, with continued breastfeeding to 12 months and beyond as recommended by the NHMRC Infant Feeding Guidelines: Information for Health Workers (2012). The ACM believes parents should be fully informed of the options to achieve this goal, one being the use of Donor Human Milk. The benefits and risks of this option are well documented; health professionals and parents need to be aware of these when making an informed decision on how they feed their infant. Key principles The benefits of exclusive breastfeeding are well researched and documented. Parents are increasingly looking for ways to optimise the start to life that exclusive breastfeeding can afford their infant. The World Health Organisation noted that “for those few health situations where infants cannot, or should not, be breastfed, the choice of the best alternative – expressed breast milk from an infant’s own mother, breast milk from a healthy wet-nurse or a human-milk bank or a breast-milk substitute… depends on individual circumstances.” (WHO, 2003) When situations occur when a mother’s own breastmilk is unavailable or insufficient to fully nourish her infant then use of donor human milk could be considered. Historically all infants were mother or wet-nurse fed. Human milk sharing occurred in Australian maternity hospitals up until the 1980s when fears re HIV and CMV stopped this practice. It re-emerged in 2006 with the first formal human milk bank in Perth, WA. There are currently both community based and hospital based donor human milk banks in Australia. In many cultures women routinely share their milk and the breastfeeding of infants in their community. Internet-based milk sharing models are emerging and families using this unregulated service need to be well informed about potential risks to make this a safe choice. In the increasingly complex biological milieu of today’s society, health professionals need to ensure it is medically and ethically safe to recommend the use of donor human milk and that the viral and bacterial transmission risks are assessed and mitigated before recommending or proceeding with its use. Do you think the title: 'Position Statement on the Use of Human Donor Milk' is appropriate? If not, why not? Do you think the Background information provided in the Draft Position Statement is adequate? If not, why not? If you have any suggested changes to the Background of the Draft Position Statement, please describe. Do you agree with the key principles as outlined in the Draft Position Statement? If not, why not? If you have any suggested changes to the Key Principles as outlined in the Draft Position Statement, 3 please describe. Ensuring Best Practice in a Health Care Setting Donors need to be carefully screened for health concerns and potential infections that can be transmitted via breastmilk. This process is the same as that which occurs in a blood bank. Additionally, questions are asked related to the donor’s health and that of her infant; any medical treatments, tests, prescribed and non prescription (complementary) medications being taken; herbal supplements; recent infections; environmental and chemical contaminant exposure; cigarette use or exposure and alcohol consumption. (NICE, 2010). During formal screening, assessment of the potential donor’s milk supply also occurs to ensure her own baby is thriving and that surplus breast milk is available to donate. International recommendations for Donor Human Milk Banks is to screen potential donors for HIV 1 and 2 antibody; Human T cell Lymphotrophic Virus I and II antibody; Hepatitis B surface antigen and Hepatitis B core antibody; Hepatitis C antibody and Syphilis antibody . Commercial Holder pasteurisation (heating to 62.5o C for 30 minutes) of the breastmilk ensures bacteria removal and virus inactivation. If this option is not available then the addition of Cytomegalovirus to the screening blood tests is recommended (Hartmann, 2007). Un-pasteurised breastmilk should contain less than 105 Colony Forming Units (CFU)/ml of total viable microorganisms, or less than 104 CFU/ml S Aureus or less than 104CFU/ml Enterobacteriaceae and no growth after pasteurisation (NICE, 2010) . In some Australian Donor Milk Banks, breastmilk is not used if it contains any Staph Aureus pre-pasteurisation. Donors require education on best practice for hygienic collection, labelling, storage and transporting of their breastmilk. Staff handling donated breastmilk should follow established procedures to ensure correct handling and storage occurs. A tracking and tracing protocol must be implemented. In the absence of a Human Milk Bank being available, it may be acceptable, feasible and cost effective to consider donors known to the mother for the provision of breastmilk. Utilise all the above mentioned precautions and testing, and ensure informed decision-making by the recipient mother and the donor occurs. Confidentiality of information and test results are a significant additional consideration. Do you agree with the considerations for Achieving Best Practice as outlined in the Draft Position Statement? If not, why not? If you have any suggested changes to the considerations for Achieving Best Practice in the Draft Position Statement, please describe. 4 Community Considerations The decision amongst friends and family to share the provision of breastmilk to an infant, either by direct feeding or via expressed breastmilk is a very personal one. As a health professional, awareness of this practice amongst clients indicates a need for careful scrutiny to ensure informed decision making by the client and others occurred. The manner in which a community donor collects and stores breastmilk for donation is very important. Information on best practice is necessary to minimise risks. Families accessing donor milk in the community need to ensure the breastmilk is transported and stored correctly and consumed within accepted timeframes. (NHMRC, 2012.) Knowledge of how to access Human Milk Banks, if in the local area, will assist any clients who may need this service. Currently, milk banks located within hospitals do not provide pasteurised donor milk for babies in the community. There is access to free and costed breastmilk sharing via commercial and non commercial sites on the internet. Caution is needed to ensure safety and honesty for both sides of this transaction. Do you think any changes to the Resources to Guide Practice are required? If so, what changes? Resources and References to guide practice Statement kindly reviewed by Kerri McEgan and Gillian Opie of Mercy Health Breastmilk Bank. Akre et al, 2011, ‘Milk sharing: from private practice to public pursuit’, International Breastfeeding Journal, 6:8. Gribble, K, 2012, ‘Biomedical Ethics and Peer-to-Peer Milk Sharing’, Clinical Lactation. http://media.clinicallactation.org/3-3/CL3-3gribble.pdf Hartmann, B et al 2007, ‘Best practice guidelines for the operation of a donor human milk bank in an Australian NICU’, Early Human Development, 83, pp 667-673. McGuire, E 2007, ‘Vertical transmission of viruses via breastmilk’, in Hot Topics, No 25, Lactation Resource Centre, Australian Breastfeeding Association. NHMRC, 2012, Infant Feeding Guidelines: Information for Health Workers, http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/publications/attachments/n56_infant_feeding_gui delines.pdf 5 National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), 2010, Donor breast milk banks: the operation of donor milk bank services (NICE clinical guideline 93), there is also a Quick Reference Guide available. www.nice.org.uk/cg93. Smith, J, 2013, ‘''Lost Milk?': Counting the Economic Value of Breast Milk in Gross Domestic Product’, Journal of Human Lactation, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23855027. Smith JP and Harvey PJ, "Chronic disease and infant nutrition: Is it significant to public health?", Public Health Nutrition, Vol.14 No.2, February 2011, pp.279-89. World Health Organisation/ UNICEF, 2003, Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding. Australian College of Midwives Draft Position Statement on the use of Donor Human Milk. Background The benefits of exclusive breastfeeding are well researched and documented. Parents are increasingly looking for ways to optimise the start to life that exclusive breastfeeding can afford their infant. The ACM believes parents should be fully informed of the options to achieve this goal, one being the use of Donor Human Milk (DHM). The benefits and risks of DHM are well documented; health professionals and parents need to be aware of these when making an informed decision on how they feed their infant. Historically all infants were mother or wet-nurse fed. Human milk sharing occurred in Australian maternity hospitals until the 1980s when fears around HIV and CMV stopped the practice. Formal milk sharing re-emerged in 2006 with the first dedicated DHM bank opening in Perth, WA. There are currently both community based and hospital based DHM banks in Australia. In many cultures women informally share their milk and the breastfeeding of infants within their local community. Internet-based milk sharing models are also emerging. These are unregulated services. Families using these services need to be well informed about potential risks to make this a safe choice. The ACM identifies four key principles to ensure the safe and appropriate use of donor human milk in Australia. Key principles 1. The ACM supports and encourages parents to exclusively breastfeed their children to six months, with continued breastfeeding to 12 months and beyond as recommended by the NHMRC Infant Feeding Guidelines: Information for Health Workers (2012). 6 2. The ACM endorses the World Health Organization’s position that the decision to use human milk from the mother, healthy wet-nurse or human milk bank in preference to a breastmilk substitute be made depending on individual circumstances (WHO, 2003). In the event of a mother’s own breastmilk being unavailable or insufficient to fully nourish her infant then donor human milk should be considered. 3. The ACM supports the formation of formal donor human milk banks in Australia and reiterates the need to follow accessible, feasible, affordable, safe and sustainable provision of breast milk to babies. 4. In the increasingly complex biological milieu of today’s society, health professionals need to ensure it is medically and ethically safe to recommend the use of donor human milk and that the viral and bacterial transmission risks are assessed and mitigated before recommending or proceeding with its use. Achieving best practice Considerations around achieving best practice in provision of DHM in health service facilities include: Donors need to be carefully screened for health concerns and potential infections that can be transmitted via breastmilk. This process is the same as that which occurs in a blood bank. Additionally, questions are asked related to the donor’s health and that of her infant; any medical treatments, tests, prescribed and non-prescription (complementary) medications being taken; herbal supplements; recent infections; environmental and chemical contaminant exposure; cigarette use or exposure and alcohol consumption. (NICE, 2010). During formal screening, assessment of the potential donor’s milk supply also occurs to ensure her own baby is thriving and that surplus breast milk is available to donate. International recommendations for Donor Human Milk Banks is to screen potential donors for HIV 1 and 2 antibody; Human T cell Lymphotrophic Virus I and II antibody; Hepatitis B surface antigen and Hepatitis B core antibody; Hepatitis C antibody and Syphilis antibody. Commercial Holder pasteurisation (heating to 62.5o C for 30 minutes) of the breastmilk ensures bacteria removal and virus inactivation. If this option is not available then the addition of Cytomegalovirus to the screening blood tests is recommended (Hartmann, 2007). Un-pasteurised breastmilk should contain less than 105 Colony Forming Units (CFU)/ml of total viable microorganisms, or less than 104 CFU/ml S Aureus or less than 104CFU/ml Enterobacteriaceae and no growth after pasteurisation (NICE, 2010) . In some Australian Donor Milk Banks, breastmilk is not used if it contains any Staph Aureus pre-pasteurisation. 7 Donors require education on best practice for hygienic collection, labelling, storage and transporting of their breastmilk. Staff handling donated breastmilk should follow established procedures to ensure correct handling and storage occurs. A tracking and tracing protocol must be implemented. In the absence of a Human Milk Bank being available, it may be acceptable, feasible and cost effective to consider donors known to the mother for the provision of breastmilk. Utilise all the above mentioned precautions and testing, and ensure informed decision-making by the recipient mother and the donor occurs. Confidentiality of information and test results are a significant additional consideration. Further best practice considerations in community settings include: The decision amongst friends and family to share the provision of breastmilk to an infant, either by direct feeding or via expressed breastmilk is a very personal one. As a health professional, awareness of this practice amongst clients indicates a need for careful scrutiny to ensure informed decision making by the client and others occurred. The manner in which a community donor collects and stores breastmilk for donation is very important. Information on best practice is necessary to minimise risks. Families accessing donor milk in the community need to ensure the breastmilk is transported and stored correctly and consumed within accepted timeframes. (NHMRC, 2012.) Knowledge of how to access Human Milk Banks, if in the local area, will assist any clients who may need this service. Currently, milk banks located within hospitals do not provide pasteurised donor milk for babies in the community. Breastmilk is able to be purchased on the Internet through commercial and non-commercial sites. The lack of a governing regulatory body to monitor quality means caution is needed to ensure safety and honesty exists. Midwives should advise mothers to exercise caution and to perform a thorough investigation of the supplier to ensure the transparency of the transaction and safety of the product prior to finalising any negotiation. Resources to guide practice Akre, J Gribble, K & Minchin, M 2011, ‘Milk sharing: from private practice to public pursuit’, International Breastfeeding Journal, 6:8. Gribble, K 2012, ‘Biomedical Ethics and Peer-to-Peer Milk Sharing’, Clinical Lactation, Available from: http://media.clinicallactation.org/3-3/CL33gribble.pdf 8 Hartmann, B, Pang, W, Keil, A, Hartman, P & Simmer K 2007, ‘Best practice guidelines for the operation of a donor human milk bank in an Australian NICU’, Early Human Development, vol. 83 no. 10, pp: 667-73. McGuire, E 2007, ‘Vertical transmission of viruses via breastmilk.’ Hot Topics, No 25, Lactation Resource Centre, Australian Breastfeeding Association. NHMRC 2012, ‘Infant Feeding Guidelines: Information for Health Workers’. Available from: http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/publications/attachments/n56_infant _feeding_guidelines.pdf National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) 2010, ‘Donor breast milk banks: the operation of donor milk bank services (NICE clinical guideline 93)’, there is also a Quick Reference Guide available. Available from: www.nice.org.uk/cg93. Smith, J 2013, ‘''Lost Milk?” Counting the Economic Value of Breast Milk in Gross Domestic Product’, Journal of Human Lactation, published online 12 July; 29 pp.537-46. Smith, J & Harvey PJ 2011, ‘Chronic disease and infant nutrition: Is it significant to public health?’ Public Health Nutrition, vol.14 no.2, pp.279-89. World Health & United Nations Children’s Emergency Fund 2003, ‘Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding’. Available from: http://www.who.int.org 9