The Water Cycle

advertisement

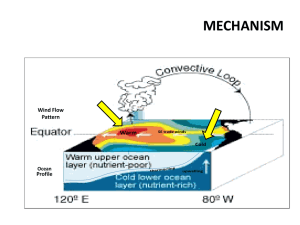

The Water Cycle If you live in the United States, there are 40 trillion gallons of water above your head on an average day. Each day, about four trillion gallons of this water fall to Earth as precipitation, such as rain, snow, or hail. Some of the water that falls to Earth soaks into the ground and provides runoff to rivers, lakes, and oceans. The remainder—more than 2.5 trillion gallons—returns to the atmosphere through evaporation, and the process begins again. This continuous process of precipitation and evaporation is called the water cycle, or hydrologic cycle. It's been going on ever since oceans were formed on this planet 3.8 billion years ago. Earth was formed 4.6 billion years ago, but water was not present at the start. At some point, possibly because of the heating of hydrogen and oxygen as Earth developed, water vapor began to form in the atmosphere. Oceans formed and the cycle began. Seventy percent of Earth is covered by water. In the atmosphere, rivers, oceans, groundwater, and elsewhere on Earth there are a total of 326 million cubic miles of water (more than 326,000,000 trillion gallons). Less than one percent of that water is present in rivers, lakes, and groundwater: we use these sources for our drinking water. Most of it—97 percent—is in the oceans. The oceans distribute heat around the planet, keeping heat and cold circulating by way of surface currents. Clouds Of the 326 million cubic miles of water on our planet, 3,100 cubic miles are found in the atmosphere. As water evaporates from the oceans, it enters the atmosphere and collects on small particles in the air as droplets or ice (a process called condensation) and forms clouds. When enough water or ice collects in a cloud, it rains. If the temperature is low enough, it snows. There are many kinds of clouds. Each signals a different kind of weather. Cirrus clouds, for example, are high up in the troposphere. Winds in the upper troposphere make these clouds look wispy and thin. Though they are composed of ice, they are usually associated with pleasant weather. Stratus clouds, which form in lower parts of the troposphere, consist of water droplets and cover most of the sky with an even, gray color similar to a fog. These clouds (as well as some cumulus, nimbostratus, and other cloud types) can signal light rain. Cumulonimbus clouds are tall, dense clouds shaped like a block or anvil. They signal thunderstorms and also spawn tornadoes, as well as other violent weather effects such as hail and lightning. El Niño In 1997 and 1998, the press was filled with reports of a weather phenomenon called El Niño. El Niño was blamed for severe flooding, drought, crop shortages, coral bleaching, and even the spread of the deadly hantavirus in some areas. What is El Niño, and how could it have such a widespread impact? El Niño's name, which means "Christ child" or "boy child" in Spanish, comes from the time of year it is likely to occur: around Christmas. It's not a hurricane or tropical storm, but a series of warm water currents that can have surprisingly serious effects. El Niño is an ocean-driven weather pattern, and it recurs every few years. It was first noticed by fishermen off the coasts of Peru and Ecuador, who observed that the warmer currents of an El Niño year tended to deplete fish populations. Warmer water temperatures reduce the amount of algae, which thrives in cooler temperatures. With less algae to feed on, fish populations decline. In 1957, Jacob Bjerknes, a scientist studying El Niño, discovered the connection between changing water currents and weather events such as increased rainfall. Every few years, western-flowing trade winds weaken, allowing warm waters to flow farther east. As these warm currents reach South America, moisture builds up in the atmosphere. Thunderstorms increase, causing heavy flooding and mudslides in some normally dry regions such as the desert areas of Peru. Until Bjerknes's discoveries, scientists thought that Peru was the only area affected by El Niño. Further research uncovered the fact that El Niño can cause weather changes in many parts of the globe. La Niña Scientists have also discovered that El Niño has a sibling: La Niña. La Niña means "little girl" in Spanish. Like El Niño, it is a recurring weather pattern, but it has the opposite effect. La Niña brings cooler water currents, usually increasing fish populations but also bringing colder winters to warm areas. La Niña and El Niño tend to alternate every few years, and in fact they are part of one phenomenon. In the 1920s, a scientist named Sir Gilbert Walker observed that barometric pressure readings in the Pacific showed a seesaw effect. When pressure increased in the eastern Pacific, pressure dropped in the western Pacific. As pressure changed, surface currents changed, causing either cooler or warmer waters to circulate. Scientists now refer to this seesaw effect as the El Niño Southern Oscillation, or ENSO.