Article: El Nino in South America

advertisement

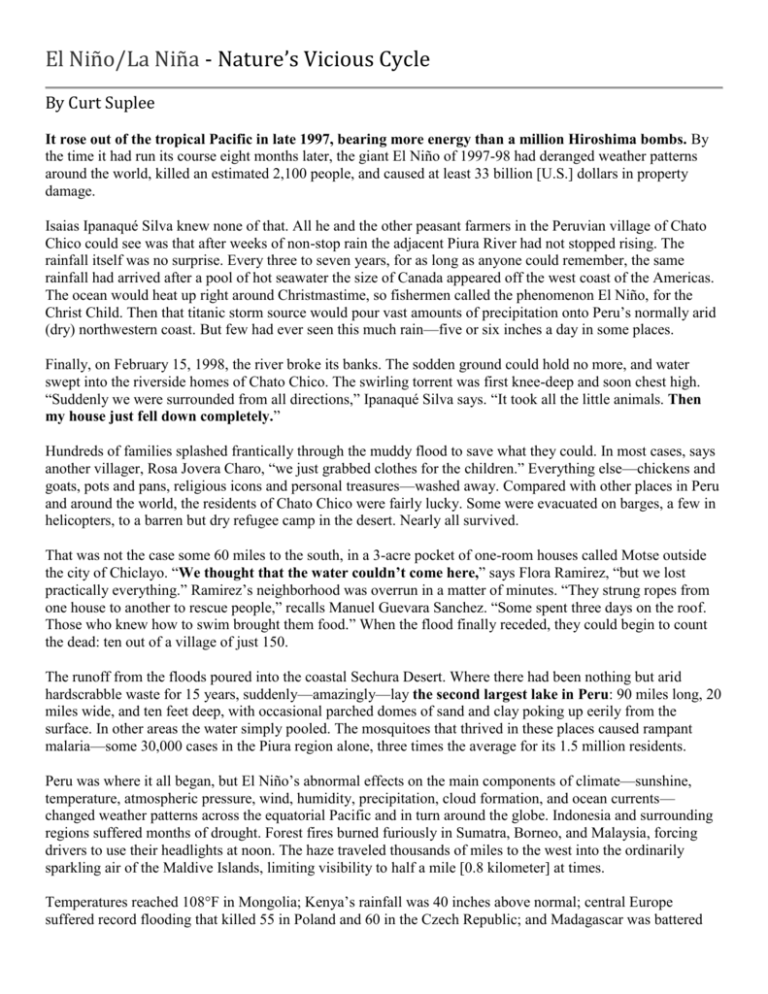

El Niño/La Niña - Nature’s Vicious Cycle By Curt Suplee It rose out of the tropical Pacific in late 1997, bearing more energy than a million Hiroshima bombs. By the time it had run its course eight months later, the giant El Niño of 1997-98 had deranged weather patterns around the world, killed an estimated 2,100 people, and caused at least 33 billion [U.S.] dollars in property damage. Isaias Ipanaqué Silva knew none of that. All he and the other peasant farmers in the Peruvian village of Chato Chico could see was that after weeks of non-stop rain the adjacent Piura River had not stopped rising. The rainfall itself was no surprise. Every three to seven years, for as long as anyone could remember, the same rainfall had arrived after a pool of hot seawater the size of Canada appeared off the west coast of the Americas. The ocean would heat up right around Christmastime, so fishermen called the phenomenon El Niño, for the Christ Child. Then that titanic storm source would pour vast amounts of precipitation onto Peru’s normally arid (dry) northwestern coast. But few had ever seen this much rain—five or six inches a day in some places. Finally, on February 15, 1998, the river broke its banks. The sodden ground could hold no more, and water swept into the riverside homes of Chato Chico. The swirling torrent was first knee-deep and soon chest high. “Suddenly we were surrounded from all directions,” Ipanaqué Silva says. “It took all the little animals. Then my house just fell down completely.” Hundreds of families splashed frantically through the muddy flood to save what they could. In most cases, says another villager, Rosa Jovera Charo, “we just grabbed clothes for the children.” Everything else—chickens and goats, pots and pans, religious icons and personal treasures—washed away. Compared with other places in Peru and around the world, the residents of Chato Chico were fairly lucky. Some were evacuated on barges, a few in helicopters, to a barren but dry refugee camp in the desert. Nearly all survived. That was not the case some 60 miles to the south, in a 3-acre pocket of one-room houses called Motse outside the city of Chiclayo. “We thought that the water couldn’t come here,” says Flora Ramirez, “but we lost practically everything.” Ramirez’s neighborhood was overrun in a matter of minutes. “They strung ropes from one house to another to rescue people,” recalls Manuel Guevara Sanchez. “Some spent three days on the roof. Those who knew how to swim brought them food.” When the flood finally receded, they could begin to count the dead: ten out of a village of just 150. The runoff from the floods poured into the coastal Sechura Desert. Where there had been nothing but arid hardscrabble waste for 15 years, suddenly—amazingly—lay the second largest lake in Peru: 90 miles long, 20 miles wide, and ten feet deep, with occasional parched domes of sand and clay poking up eerily from the surface. In other areas the water simply pooled. The mosquitoes that thrived in these places caused rampant malaria—some 30,000 cases in the Piura region alone, three times the average for its 1.5 million residents. Peru was where it all began, but El Niño’s abnormal effects on the main components of climate—sunshine, temperature, atmospheric pressure, wind, humidity, precipitation, cloud formation, and ocean currents— changed weather patterns across the equatorial Pacific and in turn around the globe. Indonesia and surrounding regions suffered months of drought. Forest fires burned furiously in Sumatra, Borneo, and Malaysia, forcing drivers to use their headlights at noon. The haze traveled thousands of miles to the west into the ordinarily sparkling air of the Maldive Islands, limiting visibility to half a mile [0.8 kilometer] at times. Temperatures reached 108°F in Mongolia; Kenya’s rainfall was 40 inches above normal; central Europe suffered record flooding that killed 55 in Poland and 60 in the Czech Republic; and Madagascar was battered with monsoons and cyclones. In the U.S. mudslides and flash floods flattened communities from California to Mississippi, storms pounded the Gulf Coast, and tornadoes ripped Florida. By the time the debris settled and the collective misery was tallied, the devastation had in some respects exceeded even that of the El Niño of 1982-83, which killed 2,000 worldwide and caused about 13 billion dollars in damage.