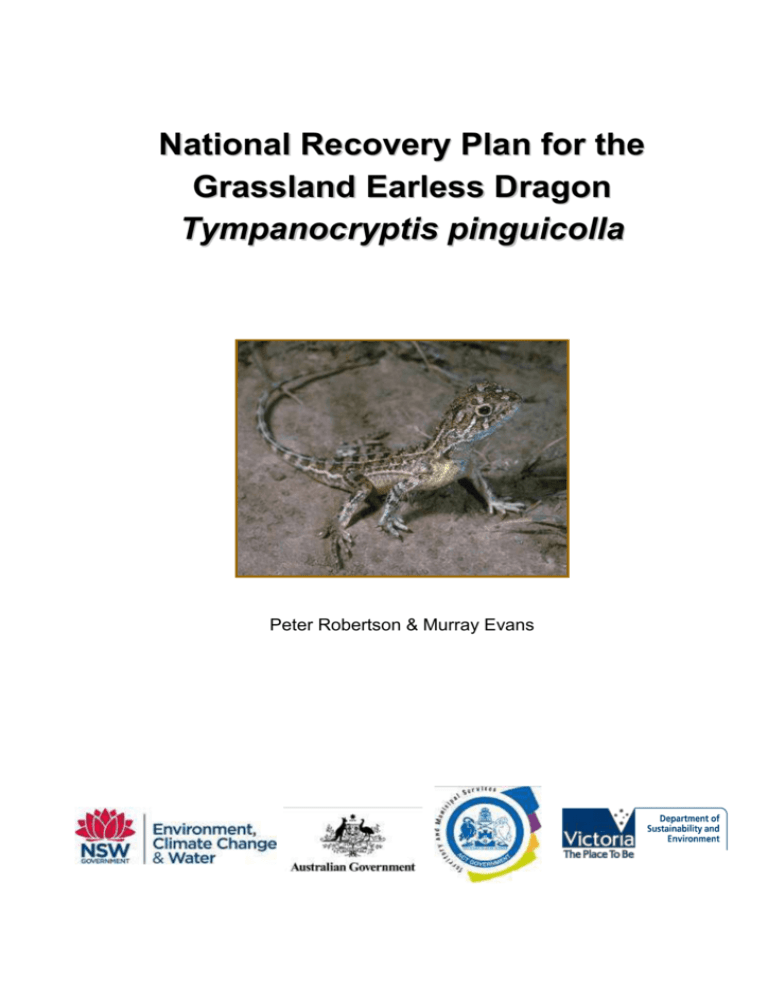

National Recovery Plan for the Grassland Earless Dragon

advertisement