Literary Symbolism

advertisement

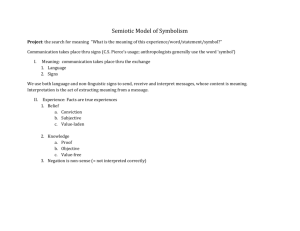

Literary Symbolism In his 1896 essay on Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry James describes the symbolic and allegoric as “a presentation of objects casting … far behind them a shadow more curious and more amusing than the apparent figure.” Allegory a narrative in verse or prose in which the literal events (person, places, and things) consistently point to a parallel sequence of symbolic ideas. This narrative strategy is often used to dramatize abstract ideas, historical events, religious systems, or political issues. The names of characters often hint at their symbolic roles. An allegory has two levels of meaning: 1. Literal: tells a surface story 2. Symbolic: level in which the abstract ideas unfold Example of allegory in literature: In James Joyce’s short story, “Araby,” the priest carries several messages. Joyce, who was an apostate (one who abandons or renounces his or her religion), implies that the Church (represented by the priest) is dead -- the Church as the former tenant of the House that is Ireland. Symbols a person, place, or thing in a narrative that suggests meanings beyond its literal sense. Symbol is related to allegory, but it works more complexly. In an allegory an object has a single additional significance. By contrast, a symbol usually contains multiple meanings and associations. Symbols in fiction are often inanimate objects. Example of inanimate object as symbol: The invisible watch ticking at the end of Faulkner’s, “A Rose for Emily,” not only represents the passage of time, but further suggests that time passes without being noticed, and that the chain is gold implies wealth and authority. Symbols in fiction are not always inanimate objects. Example: In Joyce’s, “Araby,” the very name of the bazaar, Araby—the poetic name for Arabia—suggests magic, romance, and alludes to the collection of West and South Asian folk tales, One Thousand and One Arabian Nights; its syllables “cast an Eastern enchantment over [the boy].” Conventional Symbol A literary symbol that has a conventional meaning for most readers. Example: A black cat crossing a path or a young bride in a white dress. Symbolic Characters Symbolic characters make brief cameo appearances. Such characters often are not well-rounded and fully known, but are seen fleetingly and remain slightly mysterious. Example: The brief scene with the young lady at the bazaar acts as the turning point for the story, as everything goes downhill for the boy from here. The mystical place of his mind is revealed by the girl to be enemy territory for the young Irishman, as the British are running the bazaar. Symbolic Acts A symbolic act is a gesture with larger significance than usual. Example: As the boy sets out in pursuit of a trinket for Mangan’s sister, he “held a florin tightly in [his] hand,” as if to suggest that he is blind to outside forces (such as religion or politics) that will prevent him from realizing his goal. Example: Before setting out in pursuit of the great white hale, Melville’s Captain Ahab in Moby-Dick deliberately snaps his tobacco pipe and throws it away as if to suggest that he will not let pleasure or pastime distract him from his vengeance. Recognizing Symbols Authors (and storytellers) often give symbols particular emphasis. It may be mentioned repetitively It may supply the story with a title (“Araby,” “Barn Burning”) A crucial symbol may open or close a story. An object, an act, or a character is surely symbolic (and almost as surely displays high literary art) if, when we finish the story, we realize that it was that item which led us to the author’s theme, the essential meaning.