Face of Power - Institute for Governance and Policy Analysis

advertisement

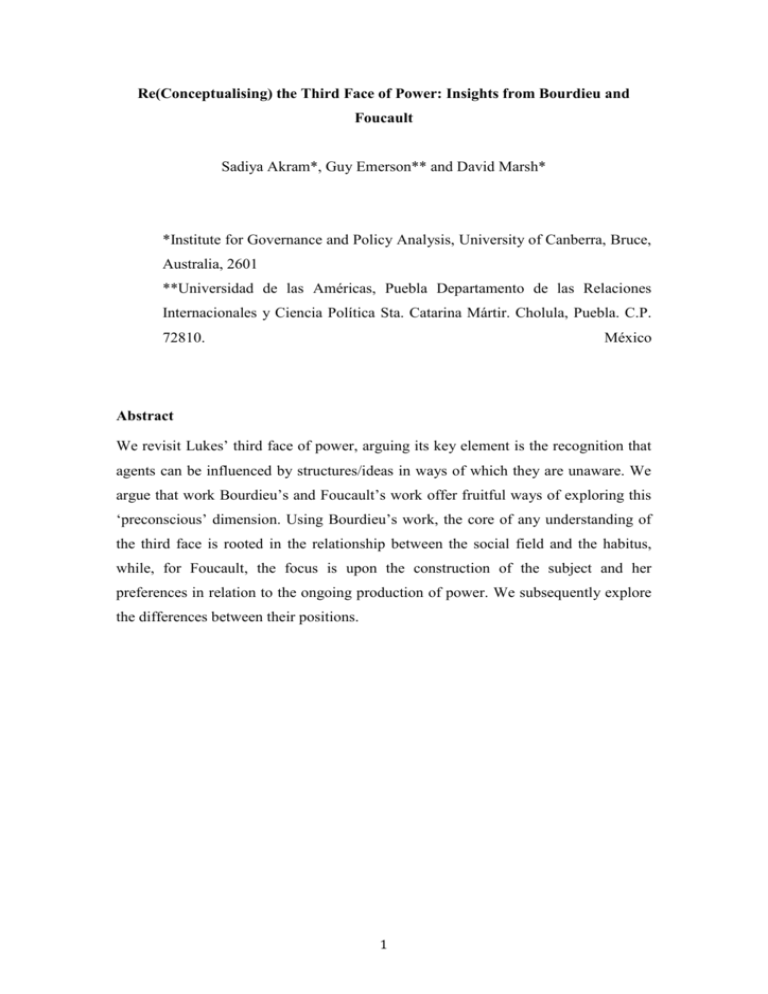

Re(Conceptualising) the Third Face of Power: Insights from Bourdieu and Foucault Sadiya Akram*, Guy Emerson** and David Marsh* *Institute for Governance and Policy Analysis, University of Canberra, Bruce, Australia, 2601 **Universidad de las Américas, Puebla Departamento de las Relaciones Internacionales y Ciencia Política Sta. Catarina Mártir. Cholula, Puebla. C.P. 72810. México Abstract We revisit Lukes’ third face of power, arguing its key element is the recognition that agents can be influenced by structures/ideas in ways of which they are unaware. We argue that work Bourdieu’s and Foucault’s work offer fruitful ways of exploring this ‘preconscious’ dimension. Using Bourdieu’s work, the core of any understanding of the third face is rooted in the relationship between the social field and the habitus, while, for Foucault, the focus is upon the construction of the subject and her preferences in relation to the ongoing production of power. We subsequently explore the differences between their positions. 1 The question of political power never goes away, neither do the problems involved in conceptualisng and measuring it. In this context, our aim is to revisit the ‘faces of power’ argument, most associated with Lukes (1974; 2005), which, in our view, is crucial to any attempt to conceptualise power. The strength of Lukes’ position was his recognition that power was not always directly exercised by an individual, or group, persuading or forcing others to act in a way in which they otherwise wouldn’t have done. The weakness of Lukes’ position was that his consideration of what he termed the ‘third face of power’ (most often seen as preference-shaping) was underdeveloped. Our aim here is to help remedy that omission by offering two, related, defences of Lukes’ position, a Bourdieusian approach and a Foucauldian approach. Both, in different, but we would argue related, ways suggest that agents are not the all-reflexive individuals posited in most of the contemporary literature on agency. Rather, they operate within a habitus, for Bourdieu, or the social unconscious, for Foucault; so both are positing a preconscious element which shapes individuals’ preferences and actions. We explore how each of these approaches can address the most common critiques of Lukes, highlighting both the similarities and differences between them. As such, this paper is divided into six substantive sections. The first section briefly outlines Lukes’ argument, before the second section considers the main critiques of it and the third briefly outlines the ways in which one can respond to such critiques using a Bourdieusian or a Foucauldian perspective. Section four and five then look at how a Bourdieusian and a Foucauldian approach respectively can be used to underpin an understanding of the third face of power. The final substantive section then focuses more specifically on the similarities and differences between the two positions. 1) Lukes and the Three Faces of Power The pluralists to whom Lukes was responding were more likely to talk of influence than power, and, following Dahl (1961), suggest that an interest group has influence over the government in so far as it can make the government do something it wouldn’t otherwise have done (a definition, of course, that has its origins in Weber). The key point here is that Dahl, like most other students of politics, thought that power was manifested in the influence that groups had over government policy, although he argued that, empirically, power in advanced liberal democracies like the US was 2 diffuse, not concentrated, a point many have endorsed, although with certain qualifications. Lukes saw Dahl’s approach as rooted in what he termed the first face of power, which involves an investigation of ‘who gets what, when and how’. This is normally termed a decision-making approach. The analytical implication of this narrow approach, however, was soon challenged by Bachrach and Baratz (1962), for ignoring ‘what does not happen’ in the decision-making process. They maintained that power is exercised, not just when making decisions, but also by excluding certain issues and participants from decision-making altogether. As such, for them, a study of power should focus not only on ‘who gets what, when and how’, but also on ‘who gets left out and how’. This is normally termed the agenda-setting approach. Here, nonparticipation in decision-making was explicitly related to power, with marginalisation no longer the result of individual apathy, but rather a product of actors’ control over what was on the public agenda. A good example here, which is well-documented, would be UK agricultural policy between the 1930s and the 1980s. During this period, there was a tight institutional link, often called a policy community, between the Government, specifically the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Fisheries and the National Farmers’ Union (Smith, 1990). Basically, this policy community negotiated about the level of production and state subsidies in an Annual Price Review. However, there was clear agreement between both parties on the broad policy, which was to grant farmers high subsidies in order to ensure high production. To put it another way, the policy options were constrained by a consensus about the boundary of the policy agenda, which reflected the power of farmers. Lukes emphasised that there was a third face of power, normally seen as involving preference-shaping, but called by Johal, Moran and Williams (2014) ‘hegemonic power’, which, in our view, seems a more accurate term. Of course, this is the most contentious face. Here, the argument is that the whole policy debate occurs within a social, cultural, economic, political and institutional framework which favours some interests over others. This position was often Marxist and rested to a significant extent on the contested idea of ‘real interests’. Here, citizens, especially disadvantaged citizens, are seen as socialised into a partial, even ‘false’, view of their own interests; a view which serves the interests of those who are powerful. So, as an example, it might be argued that, in patriarchal societies, women are socialised into accepting 3 gender roles which constrain their opportunities. It is with this aspect of Lukes’ argument that many critics take most issue. 2) Hay on Lukes and the Third Face of Power There have been a number of critiques of, and response to, Lukes’ position (Bradshaw, 1976; Ward, 1987; Hay, 2002; Guzzini, 2005; Dowding, 2006), but, given space constraints, we don’t explore them all here. Rather, we focus on Hay’s (2002) argument, which we would suggest is fairly representative of many of the critiques. Hay outlines Lukes argument in a clear and concise way, locating it within the context of the development of pluralist and behaviouralist Political Sociology. As indicated, he engages most critically with Lukes’ discussion of the third face, which he rejects for two, related, reasons. First, he is very critical of the idea of ‘false consciousness’; that is Lukes’ attempt to distinguish between subjective and ‘real’ (objective) interests. Second, he argues that Lukes conflates empirical/behavioural and normative/political conceptions of power. We briefly consider each of these critiques. Hay totally rejects the idea of ‘false consciousness’, which he finds ‘logically unsustainable and politically offensive’ (Hay, 2002, 179). More specifically, he asks the question: ‘Who is to know what (an agent’s) interests are if he is capable of misperceiving them’ (Hay, 2002, 179). Or, to put it another way, on what basis can an observer claim that s/he has privileged access to knowledge of an agents ‘real’ interests. This argument, of course, raises ontological, epistemological and methodological issues, as indeed does his second point. Hay also contends that Lukes conflates analysis and critique when discussing power. So, he argues (Hay, 2002, 183) that, within Lukes’ schema: ‘power is not so much an analytical category as a critical category whose identification is reliant upon an irredeemably normative judgement.’ To Hay, Lukes’ conception of power is negative and, as such, partial, at best. As such, Hay argues (2002, 185): ‘we must reject the behavioural definition of power and redefine the concept in such a way as to separate out these distinct normative and analytical questions that Dahl, Bachrach and Baratz and Lukes conflate.’ In attempting this move, Hay distinguishes between ‘contextshaping’ and ‘conduct-shaping’. Context-shaping refers to the agent’s ability to: ‘have 4 an effect on the range of possibilities which defines the range of possibilities of others’ (Hay, 2002, 185). In contrast, conduct shaping involves the direct influence an individual or group has over an agent. Two of us, who are critical realists, agree with Hay that it is important, although difficult, to separate analytical and normative accounts of power. However, in our view, this position is not, as Hay suggests, necessarily incompatible with Lukes’ argument. For example, critical realists defend a notion of explanatory critique. This involves a refutation of Hume’s view that facts cannot entail values and suggests that we can move from analytical to normative accounts, as long as the move occurs in that order. In our view, this distinction is important, as it ensures that the Social Sciences can engage in substantive critique of the socio-political world, but do so in a manner which is empirically informed (New, 2003). The key point here is that Hay’s approach is rooted in a constructivist ontological position, which argues that there is no real/‘objective’ world ‘out there’, which is independent of our understanding of it. Rather, the world is a social construction. This means that structures do not exist independently of agents’ construction of them; rather structures and agents are co-constituted and structures have no independent causal power. One of us has argued elsewhere (X, 2010) that this approach privileges agents and ideas, but, here, our point is that, from such a position, the idea that structures can have an effect on agents of which they are unaware, an argument at the core of Lukes’ third face of power, is untenable. In contrast, this is the position which a critical realist would defend and, while we are happy to acknowledge that this position is contestable, we reject the idea that it is ‘logically unsustainable and politically offensive.’ More aligned with Hay, a Foucauldian approach would acknowledge the social construction of reality and the co-constitutive nature of structures and agents. It would also agree on the impossibility of separating normative from empirical questions. Indeed, it could argue (somewhat cheekily) that the empirical-normative distinction is itself a product of power, reflecting an attempt by positivists to insulate themselves from any interrogation of their own implicit normative assumptions which shape their understanding of the world (cf. Foucault 1980a: 4). In addition, such an approach would also maintain that recognising the social construction of the world is merely the 5 tip of the iceberg; that this recognition obliges us to examine how this construction, and not another, came to be. It obliges us to examine the conditions of possibility that enabled it and to explore what are its consequences, in terms of enabling/disabling particular agents and particular actions. Returning to arguments concerning a subject’s ‘real’ interests, this approach avoids claims of ‘false consciousness’ by, instead, highlighting how these interests came to be – how these interests are themselves structured by a whole series of power relations that shape what can/cannot be thought and practiced. In short, it focuses on how context- and conduct-shaping are very much entwined by examining the construction of preferences, rather than measuring them up against a set of ‘real’ interests. 3) Beyond Hay: On the importance of Bourdieu and Foucault to preference shaping Rather than eliding the structure-agency debate through claims of co-constitution, we suggest that both Bourdieu and Foucault provide important insights into the mechanics involved in these intertwined processes. Indeed, as we highlight below, their immanent, or decentred, appreciations of these workings of power provide novel ways forward in thinking through the shaping of preferences. Like Hay, both Bourdieu and Foucault, to the extent that they acknowledge the structure-agency debate, emphasise their co-constitutive nature. However, in doing so, they acknowledge the limits of such a debate and the need to go further if we want properly to understand the workings of power. Bourdieu, for example, refers to the distinction – in his words a distinction between mechanism and finalism – as ‘a false dilemma’. More specifically, in relation to questions of structure he argues for the need to ‘abandon all theories which explicitly or implicitly treat practice as a mechanical reaction’. At the same time, however, he also rejects the view that this somehow implies a reduction to agency alone: we should not ‘reduce the objective intentions and constituted significations of actions and works to the conscious and deliberate intentions of their authors’ (Bourdieu 1977: 72, 73). In short, neither is adequate. Importantly, it is in this context that Bourdieu turns to his concepts of habitus and 6 practice in order to resolve this analytical tension. Rejecting abstract theoretical categories of ‘structure’ and ‘agency’ and attempts to plot interactions between the two, he argues that the site of analysis should instead be practice as it occurs within the confines of habitus. He suggests that practices in habitus are products of a scheme immanent to the practice itself – to the particular social field, for example – and not to independent structures (Bourdieu 1977: 27, 75). Indeed, this structuring of the social field is better understood as involving a perpetual state of flux, contoured through the ongoing interaction and struggle between social agents and the social field itself. Put another way, habitus and the social field are never fully synchronized, which in turn helps to avoid social determinism. The point to acknowledge then is that practice and regulation are immanent to each other, rather than being mediated either by external structures or by individual consciousness; hence the futility of an external, analytical distinction between structure and agency. Foucault adopts a similarly immanent, or decentered, take on the structure-agency debate. Like Bourdieu, Foucault stresses immanence and corporeality. Indeed, biopower and governmentality involve the analysis of how power and bodies are mutually constitutive. By highlighting the correlation of bodies and power, however, Foucault has drawn the ire of scholars like Giddens for making agency invisible. Indeed, Giddens (1984: 157) maintains, ‘Foucault’s bodies do not have faces’, so, to Giddens, any intentional attributes of individuals are foreclosed. For Foucault, however, this way of thinking about structure and agency involves a false debate. It is false because power is never exclusively repressive, but also productive. Biopower is generative of ways of being and behaving; power and agency therefore are never divorced. Indeed, the focus for Foucault is on how entire populations are animated so as to act in particular ways. Accordingly, an understanding of agency cannot be reduced to questions of intentionality, as Giddens suggests. On the one hand, such a position fails to take into consideration the generative, positive, dimension of power; and, on the other (Bourdieusian) hand, it fails adequately to acknowledge the embodied, habitual aspects that shape our actions and choices; influences that lie beyond intentionality. As such, we argue that, if Bourdieu recognizes the immanence of mechanism and finalism, then Foucault decenters structure and agency. Structure, for example, cannot 7 be understood as external, as a center of power from which particular constraints emanate. Rather, power is diffuse and productive, infiltrating everyday life. Accordingly, agency does not involve the absence of structure, but is always already structured. Put alternatively, and in terms much more aligned with the phraseology of Foucault, the workings of power are never hidden, but immanent to practice. They are the habits by which we conduct ourselves, the identities we assume and the language we speak. As such, regulation and practice are immanent to each other, rather than mediated either by consciousness or by external structures. These immanent/decentred approaches become important for the analysis to follow because they provide insights into how power, bodies, habits and preferences are generated. More specifically, in examining how our preferences are shaped, it is necessary to go beyond determining where and when subjects exert agency or reproduce ideological structures. Rather, as we argue below, the analytical tools bequeathed by both Bourdieu and Foucault provide insights into how practices are always the result of a complex interplay of forces, irrespective of the label we give them: habitus, biopower, structure or agency. Consequently, it is to a more in-depth appreciation of these perspectives that we now turn. 4) Bourdieu and the Third Face of Power Bourdieu’s concept of habitus and its relationship to power has attracted some attention, most notably in the work of Haugaard (2008), on the relationship between habitus, power and legitimacy, and by Harrits (2011), on the simultaneous existence of power as inclusion/empowerment and exclusion/dominance within the practices of the habitus. In our view, however, our understanding of these issues would be greatly enhanced if habitus was also considered in relation to Lukes’ third face of power. As argued by Haugaard (2012), there are ‘obvious affinities’ between Bourdieu’s habitus and Lukes’ understanding of the three faces of power, yet the precise implications of habitus for the third face have received little, or no discussion. a) Habitus, Field, Capital and Doxa Bourdieu’s understanding of power is developed within the context of his broader 8 theoretical approach, so power is understood in relation to his concepts of habitus, field and capital. For Bourdieu, power is culturally and symbolically created, and constantly re-legitimised through the interplay between agency and structure in habitus. The habitus, in turn, is connected to fields, because it is through habitus that power is played out differently in fields. Fields are the various social and institutional arenas in which people express and reproduce their dispositions, and where they compete for the distribution of different kinds of capital. Fields are the site of struggles for classification, where some forms of capital are deemed to be superior to others (Tyler, 2013). There are different types of field, for example, the education field or the media field, and they are the sites of contestation over power. Fields, then, should be viewed as systems involving dominant and subordinated positions, in which institutions, individuals or objects derive their distinctive properties from an internal relationship to all other positions in the field. Although they are distinct analytic concepts, Bourdieu speaks of an ‘ontological complicity’ between habitus and field, where they are mutually constituted through practice. Thus, it is through the agent’s recurrent practice that the ‘objective structures’ of the field become reflected in the ‘incorporated structures’ of habitus, which serves to reproduce the very objective structures of the field of which the habitus itself is the product. Bourdieu refers to this as ‘the circuit of reproduction’ and it is through this mechanism that social reproduction occurs. The precise relationship between field, habitus and practice is a complex and messy one to grasp in theoretical terms, yet Bourdieu suggests we must accept that this is the case because ontological concepts cannot always be neatly translated into theoretical ones and there are limits to (academic) language. As such, the aim is to move from abstract theory and locate practice at the centre of analysis (1990a: 60). People experience power differently depending upon which field they are in at a particular time. Tensions and contradictions in power relations can arise when people encounter and are challenged by different contexts, meaning that people can resist power and domination in one field and accept it in another. So, for example, women may experience different power relations in the public or private field, where they are valued in work, but experience subjugation in the home; this can be explained by their individual and group habitus and the way in which the field is constructed. 9 Fields, however, can also be the source of hidden power structures or ‘doxa’ of which people may be unaware and which may limit choices and affect preferences. According to Bourdieu, in any given field there will be different positions, those that are the part of the ‘universe of discourse’ and those that are part of the ‘universe of the undiscussed’ (1977). The latter includes the notion of doxa, which he defines through its oppositional relation to opinion. Opinions refer to the existence of beliefs and values emerging through discourse from a given field. Opinions can involve orthodox and heterodox positions, with the latter representing the potential to challenge the more dominant and widely-accepted status of the former. Opinions emerging from discourse therefore reflect awareness and recognition of the possibility of different or antagonistic beliefs. Doxa, in contrast, refers to the unstated, taken-forgranted assumptions or common sense behind the distinctions people make, which can operate as channels for the transmission of power relations. This includes aspects of the social world which remain beyond question and are therefore undisputed (Bourdieu, 1977). A further key aspect of doxa is that it favours practice reproduction, which exist outside of discourse. As such, while one role of habitus is to equip agents with a practical sense of how to act in a given social field, a doxic relation between habitus and field may limit the process of sense-making, by producing what Bourdieu calls a ‘sense of limits’ (Ellway, 2015). Related to doxa is the concept of misrecognition, which refers to cultural phenomena that anchor taken-for-granted assumptions into the realm of social life. Thus, if we are to understand precisely how power functions within any given field, it is important to identify how discourses are explicitly recognised and whether any have become misrecognised and undiscussed. For Bourdieu, forms of misrecognition are born in the midst of culture, rather than of an ideology in the Marxian sense. Misrecognition is akin to the Marxian idea of ‘false consciousness’ (Gaventa 2003), but works at a deeper level that transcends any idea that one group consciously manipulates another. It is also different from ‘false consciousness’ in that it is not a passive process, because it embodies a set of active social processes that anchor taken-for-granted assumptions into the realm of social life. All forms of power require legitimacy (Haugaard 2008) and culture is the battleground where this legitimacy is disputed, and eventually materialises, amongst agents, thus creating social differences 10 and unequal structures (Navarro 2006: 19). Field and habitus are integral to each other and the operation of doxa and misrecognition in the field help us to understand the mechanisms through which power can become invisible and yet impact on agent’s preferences. In the next section, we focus more on the construction of habitus, detailing how its pre-conscious aspect performs a vital function in this process. b) The Pre-Conscious Habitus Bourdieu’s concept of habitus has been highly influential at both a theoretical and empirical level in the Social Sciences, because, through the notion of practice, it helps us to understand how agents are affected by social structures and how social structures, in turn, are affected by agents. To put it another way, it proposes a dialectical, that is an interactive and iterative, relationship between structure and agency. It also helps us explain how structures can have an influence on agents of which they are unaware, if we acknowledge its pre-conscious elements. Whilst the concept of habitus has received much attention in the extant literature, significantly less attention has been paid to these pre-conscious elements. Here, our first point is that the pre-conscious is implicit in the operation of habitus, although this aspect has been neglected by both Bourdieu and his critics (for a development of this point see X 2012). Bourdieu’s defines habitus as 'systems of durable, transposable dispositions' (1977, 72); seeing dispositions as 'the result of an organizing action, with a meaning close to that of words such as structure' (Bourdieu, 1977, 214). In the broadest terms, habitus refers to: 'our overall orientation to, or way of being in the world; our predisposed way of thinking, acting and moving in and through the social environment that encompasses posture, demeanour, outlook, expectations, and tastes' (Sweetman, 2003, 532). Given that Bourdieu does not explicitly state his position on the pre-conscious in his work, we need to make the pre-conscious aspects of habitus explicit and show how 11 habitus is reliant on it. Bourdieu’s texts are peppered with references to the 'unconscious' and, more frequently, to how actions are 'not conscious'. As an example, in Outline of a Theory of Practice, Bourdieu writes: The 'unconscious' is never anything other than the forgetting of history which history itself produces by incorporating the objective structures it produces in the second natures of habitus... (1977, 78-79). In addition, many of Bourdieu's followers have commented on the pre-conscious aspects of habitus, most often talking of the unconscious. So, Sweetman (2003, 532) highlights Bourdieu’s argument that '(H)abitus is predominantly or wholly prereflexive, however, a form of second nature, that is both durable and largely unconscious’ (Bourdieu in Bourdieu and Wacquant, 1992, 133). Additional references to the unconscious aspects of habitus can be found in the work of Adams (2006, 514), Adkins (2003, 24), King (2000), Jenkins (2002) and Elder-Vass (2007). While the pre-conscious is implicated in how habitus functions, other critics have argued that the pre-conscious elements of habitus reduce conscious actions (ElderVass 2007; King 2000; Jenkins 2002). The issue for Jenkins (2002) and Elder-Vass (2007) is that the pre-conscious leads to a reduction in conscious thought in Bourdieu's theory. We do not have the space to address this issue now, but, following McNay, we would argue that Bourdieu does not reject reflexivity in agency, rather he acknowledges the difficulty of reflexivity (McNay, 1999; Adkins, 2003; Adams, 2006; Sweetman, 2003). The key point here is that reflexivity occurs within habitus and not from outside it, so it is not based on an 'objectivist reflexivity', where agents can stand outside of their habitus to be reflexive, rather reflexivity is understood as 'situated reflexivity' (Adkins: 2003: 25). However, our main point here is that Bourdieu, his admirers and his critics all seem to have accepted the existence of a preconscious element to habitus, although it receives very little attention in the literature. This may be partly explained by Bourdieu’s reluctance to engage with what he saw as psychoanalytical or psychological concepts, which he considered to be outside of his domain (Grenfell, 2012). c) The Pre-conscious Habitus as a Way of Underpinning the Third Face of Power 12 In our view then, habitus provides one potentially useful way of conceptualising the third face of power. Essentially, we are suggesting that habitus can structure how agents think about ‘politics’ and indeed other aspects of their lives. The pre-conscious habitus is understood as a mechanism through which the third face of power influences agency and, in turn, is reproduced in society as a social structure. The preconscious is not conceptualised as a container for negative influences on agency, but should be understood as a broader category of agency, which is neither positive nor negative, but reflects influences on agency which the agent may not necessarily filter through her more conscious capacities. This does not mean that agents are nonreflexive,1 although some may be. Rather, what we are arguing is that agents are not always reflexive, but, instead, often act habitually, in a non-reflexive, pre-conscious, way. 2 In doing so, we are critiquing the recent tendency to elide agency and reflexivity, arguing that reflexivity is but one aspect on a spectrum of agential characteristics. In our view, this is how the habitus works (for more on this point see X and Y, 2015). Agents have values/orientations on which they do not reflect; so, these values are pre-conscious. One more issue is important here, following Lukes, we would suggest that sometimes/often these values reflect the structural ‘interests’ of the powerful in society, and that, if we adopt a critical realist methodology, we can examine those relationships, which are, from that perspective, the products of deep, not directly observably, structures. 5. Foucault and the third face of power Foucault also provides potential insights into thinking through the third face of power. Indeed, the work of Foucault has already been used in this context by Hayward (2000) who discusses ‘de-facing’ power and Digeser (1992) and Johal, Moran & Williams (2014) who posit a fourth face of power. While we acknowledge these contributions, our concern here is to argue that Foucault has important insights to offer in terms of the third face of power. While it is particularly important to recognise that Foucault, 1 The literature on agency focuses almost exclusively upon reflexivity. For example, the most cited review of the concept of agency in Sociology by Emirbayer and Mische (1998, 970-973) discusses three dimensions of agency: the iterational element; the projective element; and the practical-evaluative element. In essence, all of these deal with reflexivity, the first dealing with reflexivity about the past, the second about the future and the third about the present. Similarly, Archer’s (2000, 2003) more recent work focuses on agency, neglecting structure. She identifies 5 types of ‘reflexive’, although the ‘non-reflexives’ are seen as a residual category with few members. 2 It is also worth pointing out here that the pre-conscious is not a positive or negative category and, so, it also satisfies the critical realist idea of moving from analysis to critique. 13 like Bourdieu, is concerned with more than preference-shaping, our interest centres on demonstrating how in Foucault’s view power contributes to the construction of individuals and their preferences. In particular, we focus upon the social unconscious and how it first informs the norms through which the subject is informed and later shapes her preferences. a) Power as Operational and Relational For Foucault power is not grounded in the state or in relations of production. It isn’t an attribute which is possessed and used instrumentally by agents, as it is in the mainstream understanding associated with Lukes’ first and second face. Rather, power in this setting is ‘defaced’, insofar as its operation cannot be reduced to the actions of particular agents, but, rather, permeates the social field (Hayward 1998, 2000). It is diffused throughout society, operating on and through both institutions and the bodies of agents. Consequently, his understanding of power extends beyond decision-making processes to encompass structures of thinking and behaving that were previously understood as devoid of power relations. In this way, Foucault, like Bourdieu through his notion of habitus, recognises that the effects of power are quite material insofar as its site is more often than not the body itself. Again like Bourdieu, Foucault also maintains that individual preferences are shaped in relation to the social field. For Foucault, power pervades the shaping of preferences, because, beneath intentional beliefs and practices, lie deeper, sociallyreproduced, norms that serve as a background condition to make possible the formation of interests and activities (Digeser 1992:981-982). Indeed, preferences are informed by the historic construction of norms about what are considered appropriate ways of being and behaving in that social field. For example, in a study of the marginalisation of African-American workers, Hayward (1998) shows how the preferences and agency of the workers is embedded within an earlier set of economic decisions and an historical legacy of discrimination. Here, power is not an instrument that agents use to prevent the powerless from acting freely, but rather acts as social boundaries that define the field of thinking and acting for all actors. Put simply, it acts ‘upon the boundaries that constrain and enable social action’ (Hayward 1998: 12). Accordingly, research on the formation of preferences does not focus on uncovering the subject’s ‘real’ interests, but rather on the sources and effects of these norms or 14 background conditions, irrespective of their ‘authenticity’. Importantly, however, this view of power does not eliminate the subject, or a concern with agency. Indeed, contrary to the criticism by Giddens (1984: 157) that Foucault and his followers are merely structuralists, who overlook questions of agency, Foucault’s focus is on the very construction of the subject. More precisely, rather than taking the subject, be it an individual, a class or a nation, as a given, and thereby ignoring how it came to be, the focus is on the process of subjectification. As such, it is crucial to interrogate the processes through which subjects and their preferences are constructed, understanding this construction in reference to a collection of ‘techniques of power’ that pervade society. Put simply, the Foucauldian approach focuses on how the subject is constituted through power, how power operates on and through the bodies of subjects. Here, agency is exhibited always in relation to structure, or, expressed in terms more aligned with the analysis to follow, subjects internalise numerous restraints (Johal, Moran & Williams 2014: 401). Consequently, an analysis cannot begin with an already-given, autonomous, subject who precedes the operation of power, as in positivist, phenomenological or other approaches, but requires an interpretivist approach that is able to interrogate the rules which govern the various social practices that produce subjects and their preferences. This approach is potentially important for discussions of the third face of power insofar as Foucault specifically examines how mechanisms of power are concerned with the reproduction of preferences that ensure the management and administration of social life. Like Bourdieu, he maintains that the reproduction of social norms lies beyond the state itself, as it encompasses: ‘a tightly knit grid of material coercions rather than the physical existence of a sovereign’ (Foucault 1980b: 104). Indeed, power relations are simultaneously local, unstable and diffuse, and thus do not emanate from a central point (Deleuze 1988: 73). As such, power is not conceived exclusively in a negative fashion, as excluding, repressing, censoring, abstracting, masking and/or concealing, but also as positive and enabling, as producing domains of truth and appropriate ways of behaving (Foucault 1995: 194). For a Foucauldian, power thus works to incite, reinforce, control, monitor, optimise and organise. In short, it is generative, making subjects grow and ordering them, rather than dedicated to impeding them, making them submit or destroying them (Foucault 1978: 133). It is in this context that the generation of the subject and her preferences involves a 15 multiplicity of interrelated factors. b) Understanding the social unconscious One way of tying together Foucault thinking on power and the formation of individual preferences is through an appreciation of the social unconscious. This involves linking Foucault’s later work, particularly the History of Sexuality (1978) and his lectures at the Collège de France in the late 1970s, with its interpretation by colleague and one-time friend Gilles Deleuze, specifically, but not exclusively, in Foucault (1988). At its most basic, the social unconscious concerns the inter-relationship between the social field and the unconscious. This is important for our purposes, to the extent that the individual unconscious, or in their words psyche, is composed of the same kind of material as society, bodies, relations, productions and events. Given that it is produced in the same way as society, the psyche has no primacy, nor claim to originality, in relation to the construction of preferences. To this extent, the unconscious is not some separate, autonomous entity; a latent source of energy that is uniquely individual and, therefore, pushes and pulls us in a distinctive manner. Rather, it too is constructed by, and therefore invests in, the social field, with our preferences thus continually reproduced in relation to this social field. Put another way, our preferences cannot be reduced to subjective intention alone, but are shaped by social, and highly political, forces, whether we are mindful of them or not. As such, interaction with the social field is central to the construction of the unconscious and the preferences therein. Here, the psyche is produced in such a manner that a small portion of the social field is internalised within the subject. For example, it is internalised as the memories we have of how to act in such a situation, or as the habits we form in our everyday interaction with the world. Put alternatively, and in relations to the work of Deleuze, the psyche is formed through a process of folding, of taking external social elements and internalising them as one’s own, again whether we are mindful of it or not. Indeed, for Deleuze (1988: 97) it was through such an approach that Foucault discovered a way of ‘folding the line of the outside’, whereby the outside is ‘interiorised’. What this means for the construction of social norms, and later the elaboration of preferences, is that they are continually produced/reproduced through how we conduct ourselves in the world. That is, if the inside (the psyche) is constituted 16 through a folding of the outside (the social field), then the relation to oneself – how I think and how I conduct myself – is similar to relations already apparent in the social field. Relations to oneself become ‘a principle of internal regulation’, formulated in a manner consistent with the power dynamics of family, race, class and gender apparent in the social field (Deleuze 1988: 100). To put it crudely, I come to identity myself in the same way as I am stratified in the social field. I continuingly modulate myself within this normative band of what is, and is not, recognised as a legitimate way of being and behaving (Rose 1996; Miller and Rose 2008). However, in order to move from this (social) unconscious to the shaping of preferences, it is necessary to introduce a level of individual agency; which involves the subject identifying, or, better, acting (consciously or not), in accordance with these social norms. This overlap can be examined in relation to language. For example, take a seemingly innocuous statement about our identity: ‘I am of this race, class, gender and/or political persuasion’ (Goodchild 1996: 86). In this setting, the subject can be seen to have internalised a series of social norms in regards to race, class, gender etc. insofar as she not only constructs herself (‘I am of this race…’), but also fixes relations between herself and other detached objects or persons (‘I am not of that race…’). Not only must she identify with one or the other, but she must also accept the broader system of socially-produced differentiations, or fall outside. That is, she is forced into this social field, forced to comport herself according to the norms associated with this particular subject position. Should she ignore such regimentation, then she would fall into the ‘black night’ of the unrecognisable (Deleuze and Guattari 1987: 76-8). To this extent, the statement can be read as an auto-stratification, or fixing of flows, between the social field, the unconscious and her preferences. In other words, through the statement ‘I am of this race, class, gender and political persuasion’, the individual is compelled, again, whether she is mindful of it or not, to internalise a series of social constructed ways of being and behaving so as to be recognised as of that race, class, gender, and political persuasion. c) The social unconscious as a way of underpinning the third face of power Translated more directly into discussion of the third face of power, the claim is that, as well as comporting herself in accordance with a series of social norms, the subject also conjugates within herself socially-produced preferences (Deleuze and Guattari 17 1987: 85-6). The synthesis between the unconscious and the social field is thus no free-for-all, poly-vocal, process of multiple transitions, but a stratifying process. We come to evaluate ourselves in relation to a series of boundaries between particular terms that impose order upon our world and through which we reproduce this social formation in how we talk and act. Accordingly, and this is the key point, it is through how we talk and act that it is possible to chart this stratifying process and thus access the implicit assumptions that shape our preferences. The focus, therefore, does not centre on the psyche itself, but on visible, exterior, relations, like the conjunction between multiple power relations and the subject’s identification with these conjunctions. Put another way, rather than tunnelling into the pre-conscious, a Foucauldian approach operates in practice on the surface of thought: on what is said and on what is put into action. We are thus able to explore the third face of power by charting a subject’s language and behaviour. 6) Bourdieu, Foucault and the third face: Similarities and Differences We have argued that one can defend Lukes’ idea of a third face of power using either a Bourdieusian or a Foucauldian perspective. Here, we briefly discuss the similarities and differences between these approaches. In so doing we not only respond to Hay’s critique of Lukes, but also detail how both perspectives can help chart the construction of preferences. While Bourdieu and Foucault have different conceptualisations of power and approach the issue from different theoretical traditions, they share an understanding that agents’ preferences are shaped by processes of which they are not necessarily aware; what we have termed a pre-conscious, or a social unconscious, dimension. Such an approach does not undermine the autonomy of agency or the subject, which is Hay’s main concern about Lukes’ third face of power, but, rather, acknowledges the subtle, but crucial, way in which power operates to affect individuals. Moreover, Bourdieu and Foucault are both concerned with the same question: how does a social system, despite obvious inequality and disadvantage, survive without depending upon explicit forms of repression or physical coercion to maintain order? As such, both are interested in uncovering the hidden, and often unobservable, nature of power and agree that we should move away from the state-based notion of centralised power and 18 control that was the concern of theorists such as Marx and Weber. If we focus first on what they share, here there is clearly methodological agreement. Both see the first task as isolating the operation of power within a population, a discipline or a particular social field, but, at the same time, see such a particular operation of power as reflecting the workings of power in society at large. Foucault, for example, explores the dynamics proper to a technology of power, charting the historical production of discourses on madness, so as to tell a larger story about Western civilization. Similarly, Bourdieu isolates communities – in Algeria, for example – or particular social fields – the educational field, the artistic field, the commercial field – through which a picture emerges of broader contemporary society. The unit of analysis – be it a particular discourse, Kabylia, or a social field – is itself generative of the theory. For Foucault, the procedures and details of clinical control become micro-apparatuses or technologies of power through which to understand power in the contemporary setting. For Bourdieu, the strategies, the private experiences and/or that which is socially inscribed on the body as habitus, are all utilized to explain the reproduction of social order more broadly. Both Foucault and Bourdieu then are interested in the construction and consequences of power and how it is continually articulated through the subject. Despite this same starting point, however, Foucault’s understanding of this issue is different to Bourdieu’s because of his relational view of power, where power is a function of a network of relations between subjects. Power has no central focus here and cannot be exercised by particular agents or institutions. Rather, power operates through impersonal mechanisms of bodily discipline that often escape the consciousness of the subject. Accordingly, power is irreducible to subjects who exercise it over others with the sanction of ‘right’ or law. This is not to suggest that the ubiquity of power means that it flows equally among social agents. On the contrary, in the panoptical setting of Foucault’s earlier work, the subject of surveillance does not have the reciprocal power to observe the observer. Similarly, in the bio-political setting of his later work, we see how the individual’s deviance is investigated, with power asymmetrically in favour of the person(s) whose access to privileged forms of knowledge grants them the authority to pass judgement. Accordingly, it is difficult to identify a priori any determinate social location in which power is exercised or resisted. Rather, such a move depends on an historical 19 (genealogical) analysis of madness, the clinic or sexuality, so as to chart the formation and consequences of power on and through the subject. At first glance, it might be suggested that Bourdieu also offers a relational view of power, because, for him also, power is dispersed amongst the social body. However, for Bourdieu, power is linked to resources (capital) and power can be possessed by agents, thus identifying agents, and their habituses, as a site of analysis. As such, Bourdieu’s theory of practice as the symbolically mediated interaction between habitus and social structure avoids these problems by connecting relations of domination both to identifiable social agents and to the institutions of the state. Accordingly, Bourdieu seems to offer a more empirically sensitive analytical framework for decoding impersonal operations of power than does Foucault. It thus potentially provides a more immediate framework to examine individual agency and preferences, while for Foucault it is a question of deeper historical investigation into the construction of both the subject and her preferences. In Conclusion The core claims of this article are: first, that any full conceptualisation of power needs to move beyond a focus on just the first and second faces; second, that in conceptualising the third face we need to recognise that agents can be influenced by structures and/or ideas in ways of which they are unaware; and, third, that both Bourdieu and Foucault, in related, but different, ways, offer fruitful ways forward in exploring that third face. Crucially, they share an understanding that agents’ preferences are shaped by processes of which they are not necessarily aware; what we have termed a pre-conscious, or a social unconscious, dimension As such, they offer us a more nuanced way of dealing with the subtleties of the third face. Utilising Bourdieu’s work, the core of any understanding of the ‘third face’ would involve an appreciation of the relationship between the social field and the habitus, while for Foucault the focus is upon the construction of the subject and her preferences in relation to the ongoing production of power. However, we need also to recognise the major difference between Bourdieu and Foucault’s approaches. For Foucault, power has no central focus; it is inscribed in 20 institutions, processes, practices and people. As such, it is not exercised by particular agents or institutions. In contrast, for Bourdieu, power is linked to resources, to ‘forms of capital’. Different agents possess different mixes of resources and those with more resources are likely to exercise power over those with less. Of course, throughout this article we have side-stepped a crucial aspect of the faces of power debate; the methodological issues involved in studying the third face of power. We are not underplaying these problems, but our argument is that we need to be clear about how we are conceptualising the third face of power before we move to examining it empirically. Bibliography Adams, M. (2006), ‘Hybridizing Habitus and Reflexivity’, Sociology. Vol. 40. No. 3. 511-528. Adkins, L. (2003),.‘Reflexivity: Freedom or Habit of Gender? ‘, Theory, Culture and Society. Vol. 20. No. 21. 21-42. Alexander, J, C. (1995),. ‘The Reality of Reduction’ (128-202), in Fin de Siècle Social Theory. London: Verso . Archer, M. (2000), Being Human: The Problem of Agency (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press). Archer, M. (2003), Structure, Agency and the Internal Conversation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press). Bachrach, P. and Baratz, M.S. (1962),. ‘The Two Faces of Power’. American Political Science Review.. Vol, 56, 941- 52. Bourdieu, P. (1977), Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Bourdieu, P., & Wacquant, L. J. D. (1992),. An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology. Cambridge: Polity Press. Bradshaw, A. (1976), A Critique of Steven Lukes’ Power: a Radical View’, Sociology, 10, 1, 121-127. Dahl, R. (1961) ,- Who Governs? Democracy and Power in an American City. New Haven CT: Yale University Press. Deleuze, G. (1988) Foucault. Trans. Sean Hand. London: The Athlone Press. 21 Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F. (1988) A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Trans. Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Dowding, K. (2006), here-Dimensional Power: A Discussion of Steven Lukes’ Power: a Radical View’, Political Studies Review, 4, 2, 136-145. Elder-Vass, D. (2007). ‘Reconciling Archer and Bourdieu in an Emergentist Theory of Action’, Sociological Theory, 25(4), 325–346. Ellway, B.P.W & Geoff Walsham, G.(2015). A doxa-informed practice analysis: reflexivity and representations, technology and action. Info Systems. 25, 133–160 Emirbayer, M. and Mische, A. (1998), ‘What Is Agency?’, American Journal of Sociology, 103, 962-1023. Foucault, M. (1978) The History of Sexuality, Volume 1: An Introduction. Trans. Robert Hurley, New York: Pantheon Books. Foucault, M. (1980a) ‘The History of Sexuality: Interview’, Oxford Literary Review 4(2): 3-10. Foucault, M. (1980b) Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings 1972-1977, London: Harvest Press Foucault, M. (1995) Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Trans. Alan Sheridan, New York: Vintage Books. Gaventa, J. (2003). Power after Lukes: a review of the literature. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies. Giddens, A. (1984) The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration. Berkeley: University of California Press. Goodchild, P. (1996) Deleuze and Guattari: An Introduction to the Politics of Desire, London: Sage Publications. Grenfel, M. (2012). Pierre Bourdieu: Key Concepts. London: Acumen Guzzini, S. (2005), ‘The Concept of Power: a Constructivist Analysis’, Millenium, 33, 3., 405-521. Harrits, G. S. (2011). ‘Political Power as Symbolic Capital and Symbolic Violence‘, Journal of Political Power. Vol. 4 (2). 237-258. Haugaard, M. (2008). ‘Power and Habitus’. Journal of Political Power. Vol. 1 (2). 189 - 206. 22 Haugaard, M. (2012). Rethinking the Four Dimensions of Power. Journal of Political Power 5(1): 35-54. Hay, C. (2002), Political Analysis. Basingstoke: Palgrave. Hayward, C. (1998) ‘De-Facing Power, Clarissa Rile Hayward’, Polity, Vol. 31, No. 1, pp. 1-22. Hayward, C. (2000) De-Facing Power. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Jenkins, R. (2002), Pierre Bourdieu. London: Routledge. Johal, S.., M. Moran and K. Williams (2014). ‘Power, Politics and the City of London after the Great Financial Crisis.’ Government and Opposition, 49, pp 400-425. King, A. (2000), ‘Thinking with Bourdieu Against Bourdieu’, Sociological Theory, Vol. 18. No. 3. 417 - 433. Lukes, S (1974, 2005), Power: A Radical View. 2nd Ed. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. Potter, G. (2000). ‘For Bourdieu, Against Alexander: Reality and Reduction’. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, Vol. 30. No.2. Miller, P. and Rose, N. (2008), Governing the Present: Administering Economic, Social and Personal Life. Cambridge: Polity. McNay, L. (1999). ‘Gender, Habitus and the Field: Pierre Bourdieu and the Limits of Reflexivity’, Theory, Culture and Society. Vol. 16. No.1. 95-116. Navarro, Z. (2006). In Search of Cultural Intepretation of Power. IDS Bulletin 37(6): 11-22. New,C. (2003), ‘Feminism, Deconstruction and Difference’ in J Cruickshank (ed.) Critical Realism, the Difference it Makes, London: Routledge Rose, N. (1996) Inventing ourselves: Psychology, power, and personhood. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Sayer, A. (2000). Realism and Social Science. London: Sage. Smith, M. (1990). The Politics of Agricultural Support: the Development of an Agricultural Policy. London, Dartmouth. Sukhdev J., M. Moran and K. Williams (2014). ‘Power, Politics and the City of London after the Great Financial Crisis.’ Government and Opposition, 49, pp 400425. 23 Sweetman, P. (2003), ‘Twenty-first Century Dis-ease?’, The Sociological Review, Vol. 51 (4) 529-54. Tyler, I. (2013). Revolting Subjects: Social Abjection and Resistance in Neoliberal Britain London, Zed Books. Ward, H. (1987), Structural Power – A Contradiction in Terms?, Political Studies, 35, 4, 593-610. 24