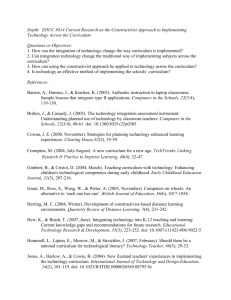

leisure intervention

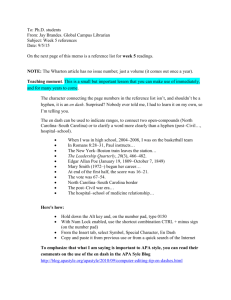

advertisement