Writing to Learn

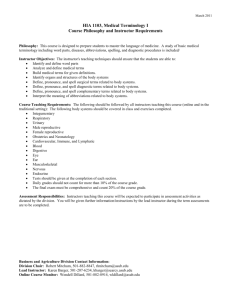

advertisement

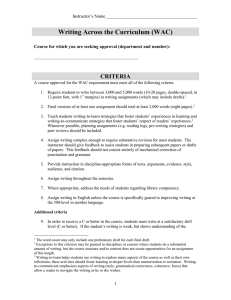

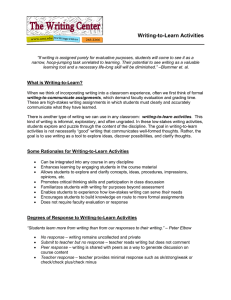

Writing to Learn A Cross-Disciplinary Writing across the Curriculum Brown Bag Presented by the UW-Superior Writing across the Curriculum Program October 8, 2010 What is “Writing to Learn”? According to the WAC Clearinghouse (http://wac.colostate.edu/intro/pop2d.cfm), writing-tolearn activities are typically “short, impromptu or otherwise informal writing tasks that help students think through key concepts or ideas presented in a course. Often, these writing tasks are limited to less than five minutes of class time or are assigned as brief, out-of-class assignments.” What are some examples of Writing-to-Learn activities? Journals for various purposes and with varying degrees of structure as defined by the instructor: Journal types according to purpose: --Exam preparation journals --Contemporary issues journals --Reading logs --Learning logs Journal types according to amount of structure: --Unstructured --Semi-structured --Guided Reading Responses Freewriting Microthemes Double-Entry Notebooks (Reflect on the course material on one side; later, reflect on those reflections on the other side.) “What I Observe/What I Thought” Lab Notebooks Thought Letter Discussion Board Comments and Responses (Many of these examples come from John C. Bean’s Engaging Ideas, San Francisco: Jossey Bass, 2001.) How should an instructor respond to and evaluate such writing? Writing-to-learn activities are regarded as “low-stakes” writing—meaning that any one such assignment is “not worth much” (not worth many points, that is!). Such work is typically NOT evaluated for structure, grammar, spelling, and the like. Students receive credit (perhaps via a check plus/check/check minus system), the instructor typically provides brief written comments and responses to the piece, and students also may receive feedback from other students when the writing is used in class as a discussion starter. What are the benefits of Writing-to-Learn activities? In Language Connections: Writing and Reading Across the Curriculum,” Toby Fulwiler and Art Young speak of the theory behind writing to learn: Writing to communicate … means writing to accomplish something, to inform, instruct, or persuade. . . . Writing to learn is different. We write to ourselves as well as talk with others to objectify our perceptions of reality; the primary function of this “expressive” language is not to communicate, but to order and represent experience to our own understanding. In this sense language provides us with a unique way of knowing and becomes a tool for discovering, for shaping meaning, and for reaching understanding.” (quoted on the WAC Clearinghouse “A Fuller Definition of Writing To Learn” web page, http://wac.colostate.edu/into/pop4a.cfm). Thus Writing to Learn emphasizes critical thinking and reflection. As an added benefit, students get sheer writing practice via writing to learn activities. Using writing to learn activities is great for classes in which it would be difficult (due to class size, the nature of the class, and so on) to have students do more extensive, more formal writing. In such cases, including such writing activities gives instructors a chance to simply keep students writing and to show them that writing is valued everywhere in academia, no matter the type of course. (Of course, it is also a beneficial approach in classes in which other, more formal writing will take place.) (See also Peter Elbow’s comments on “Specific Uses and Benefits of Low Stakes Writing” on the attached sheet.) What are the common objections to Writing to Learn activities, and how do advocates for the approach counter these objections? --Instructors, as Bean puts it, may envision stacks of journals they would have to cart home in wheelbarrows to read. Yet one need not read everything in detail, and there are ways around having to have students turn in big journals. See the list of potential types of activities above; some are not at all wheelbarrow-inducing! --Instructors fear students will see such writing activities as busy work. And some students may— perhaps due to their individual learning styles, our grade-oriented culture, students’ view that getting the “right answer” is what’s important always, or an instructors’ failure to integrate the assignments into the fabric of the course. The answer is to help students see the value of the assignment: instructors can use the responses in class, let students know that expert writers do this sort of writing, and model it themselves. (For instance, if an instructor has asked students to freewrite for five minutes, he or she would freewrite along with them.) --Instructors may feel that such writing is, according to Bean, “junk writing that promotes bad habits” (100). But instructors can explain the distinction between this type of writing and more formal writing they may be doing in the course as well; this is a teachable moment on the subject of rhetorical contexts and audience expectations. (And, according to Elbow, this type of writing actually helps with students’ more formal writing!)