Sydney O`Hare Delegate, Republic of Spain Spain and

advertisement

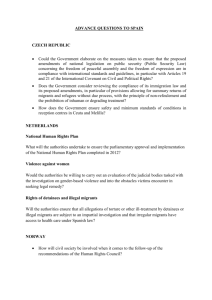

Sydney O’Hare Delegate, Republic of Spain Spain and Safeguarding the Rights of International Migrant Populations Spain has always been immigrant-friendly, with an ever-growing immigrant population. In 1996, the amount of emigrants in Spain made up for 1.37% of the population. In just ten years, it grew to 8.75%. Migrant workers tend to be young adults and work primarily in construction, agriculture, hospice, and restaurants. Primarily from Morocco, Ecuador, Romania, England, and Colombia, migrant workers earn little money for the long hours they work. Some workers get passes into Spain and never leave, illegally living in forests near small villages. Migrant workers tended to take jobs no one else wanted, leading to little pay and few rights. But in 2000, Spain recognized their plight with the Organic Law. It was in 2000 that migrant workers gained specific rights in Spain. Before this law, migrants’ basic human rights were protected by the EU, but no specifics were laid out. Spain’s Organic Law of 2000 helped manage the influx of workers, but still gave them rights. It was reformed in 2009, when migrants practically received their own Constitution. The 2009 version gave workers the rights to healthcare, education, basic social services, legal aid, and protection from discrimination. Even the law was passed after the economic meltdown of 2008, Spain’s government felt migrant workers deserved funding and basic human rights. Even though the Organic Law was helpful, migrant workers in Spain still suffer today because the law was not properly enforced due to the current economic unrest in Spain. When the 2008 recession occurred, Spain was forced to cut their out-of-control spending. These cuts meant migrant workers receive few to none of the benefits once promised to them. The UN must assist the migrants by helping them build proper homes or finding food, since homelessness and hunger are abundant in Spain. The Organic Law of 2009 stated Spain must assist in the emigration of workers to their homelands. This would be costly, and Spain has nothing to spare. The UN should provide inexpensive or even free travel home for migrant workers who no long want to remain in Spain. To prevent profiling, workers should attempt to register and say if they wish to remain in or leave Spain. This plan may seem tedious, but helping the migrant workers achieve what they had recently been promised would be worth the hardships. By giving migrant workers the rights they had previously been promised, the UN would help Spain solve one of its many problems.