The World`s Columbian Exposition Collection at the State Library of

advertisement

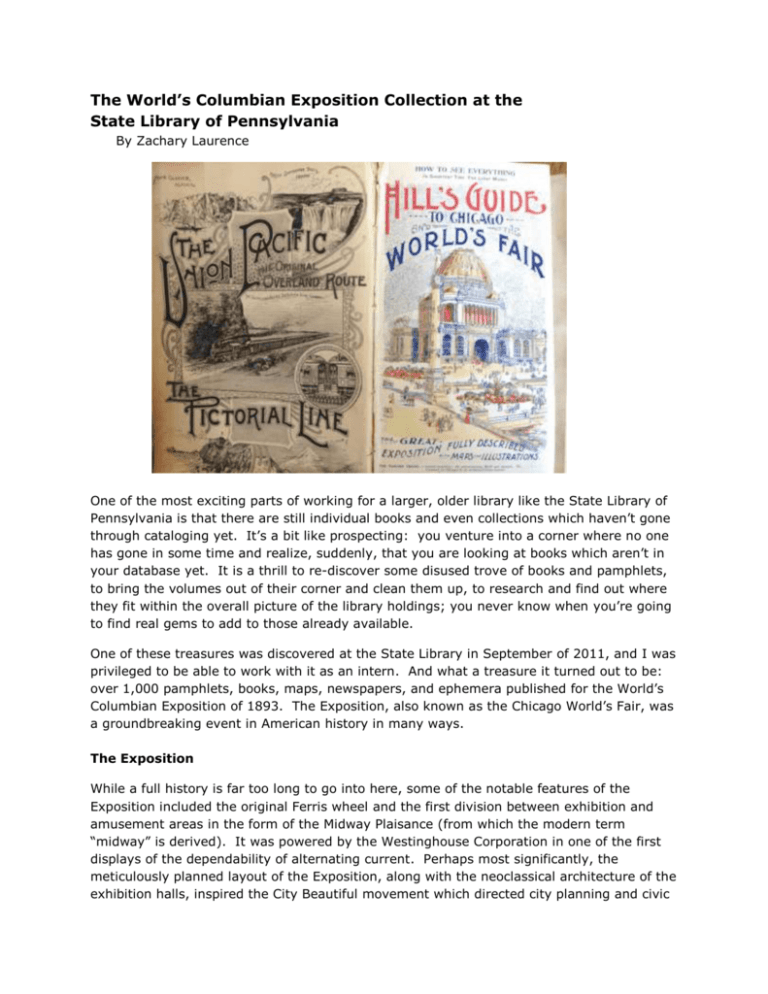

The World’s Columbian Exposition Collection at the State Library of Pennsylvania By Zachary Laurence One of the most exciting parts of working for a larger, older library like the State Library of Pennsylvania is that there are still individual books and even collections which haven’t gone through cataloging yet. It’s a bit like prospecting: you venture into a corner where no one has gone in some time and realize, suddenly, that you are looking at books which aren’t in your database yet. It is a thrill to re-discover some disused trove of books and pamphlets, to bring the volumes out of their corner and clean them up, to research and find out where they fit within the overall picture of the library holdings; you never know when you’re going to find real gems to add to those already available. One of these treasures was discovered at the State Library in September of 2011, and I was privileged to be able to work with it as an intern. And what a treasure it turned out to be: over 1,000 pamphlets, books, maps, newspapers, and ephemera published for the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893. The Exposition, also known as the Chicago World’s Fair, was a groundbreaking event in American history in many ways. The Exposition While a full history is far too long to go into here, some of the notable features of the Exposition included the original Ferris wheel and the first division between exhibition and amusement areas in the form of the Midway Plaisance (from which the modern term “midway” is derived). It was powered by the Westinghouse Corporation in one of the first displays of the dependability of alternating current. Perhaps most significantly, the meticulously planned layout of the Exposition, along with the neoclassical architecture of the exhibition halls, inspired the City Beautiful movement which directed city planning and civic architecture (including that in the Pennsylvania State Capitol!) for more than half a century afterward. The Exposition also produced a truly massive amount of printed material. Every state and territory which existed in America at the time had its own displays and brochures. Countries from all over the world used the Exposition to spread information concerning their technology, national products, art, culture, and tourism possibilities. Organizations such as Westinghouse Electric Corporation, Union Pacific Railroad, Battle Creek Sanitarium (home of John Harvey Kellogg), and many others advertised new products, innovations, and research. Social commentary abounded, addressing topics such as poverty, cruelty to animals and children, vivisection in scientific research, and racism, particularly in the exclusion of African-Americans from the teams constructing and staffing the Exposition. And of course many different guidebooks and maps were produced to assist visitors in locating what they wanted to see. The Collection When this massive amount of material was discovered at the State Library, there was some confusion as to where it had come from. The various items had been bound together into volumes, and while a cursory inspection revealed that many of the volumes had common themes (for instance, an entire volume was devoted to college brochures from New York State) there was no discernable order to the collection, and no indication of how or why it had arrived. At first it was thought that this might have been a common collection sent to many libraries by some organization at the Exposition itself. However, the Rare Books Librarian, Iren Snavely, discovered a collection of State Librarian’s Reports from the 1890’s which shed some light on the matter. In the Report of the State Librarian for 1893, on page 3, State Librarian William Egle reveals the origin of the collection: “ The World’s Columbian Exposition at Chicago has given occasion for the publication of more literature – national, state and municipal, - than any event which has ever transpired in America…Embracing the opportunity, I secured, chiefly by donation, a collection, unique and complete…This Library is the only in the world which succeeded in gathering up these epherma, many really of the greatest value…” While Egle may have considered the collection to be of greatest value, the years between then and now had not been kind. As I mentioned, the various materials had been bound into volumes. The bindings, unfortunately, were in very poor condition by the time the collection was re-discovered. In many cases the boards, attached in the first place by short lengths of twine, had broken free of the volume and were missing. The glue which held the spines of the bindings together was old and decaying, and many of the original leather outer spine pieces had fallen off or worn away, leaving at best a paper spine liner. The items themselves were in somewhat better condition, but there were still problems. The materials had been bound by subject regardless of the size of the item, and arranged so that the tops of the items were level with each other. As such very small pamphlets hung from the binding, creating pressure on the binding, while very large pamphlets, because of missing boards, might be supporting all of the weight of the volume along their bottom edges. In the worst cases, short but thick or heavy pamphlets were hanging from the binding while taller, thinner pamphlets supported the weight. As you can imagine, many of the taller pamphlets ended up bent in various ways along the edges. Two additional factors compounded these problems. First the paper, while in many cases of high quality, was still of 19th century origin and thus was quite brittle in some instances. In certain materials, particularly the maps and newspapers, the paper had become so brittle that it began to crumble when touched. Secondly it appears that the bindings were readymade before the materials were sewn together and placed into the binding. With many of the larger materials, again particularly the maps and newspapers, this meant that the material was larger than the casing into which it was being put. Many of these larger items were folded over to make them fit within the boards, which increased problems with brittleness. Finally, it appeared that the collection had not been moved in some time. The last checkout date which was found in any of the books was August of 1914, and while the volumes had likely been moved since then, little if any use was made of them. As such there was a large amount of dust built up within the volumes, particularly where item sizes differed and there was a space within the text block formed by the bound pamphlets. The Project When I began to work with the collection as an internship project, I had three major goals. The first goal was to determine what materials were in the collection and how common these materials were. My second goal was to remove as much of the built up dust from the items as possible without causing further damage. Finally, I was to evaluate how best to preserve the collection for the future. With each volume of the collection, I began by describing the condition of the volume, identifying major problems with the binding and the items inside, and providing a list of possible actions for preservation. Some items and volumes had individual repair recommendations, but in most cases I ended up recommending separate storage of the items in the volume, re-casing if the spine of the text block was not too badly damaged, or storage in a phase box or other protective enclosure. Once these recommendations had been recorded, I set about cleaning the items within each volume. I used a soft brush to sweep away as much dust as possible from the edges and item covers, working from the gutter of the item outward. In cases where a significant amount of dust was still present, I then used an Absorene soot sponge to gently wipe up the remaining dust, again working from the gutter outward. For those not familiar with Absorene, it is a rubberized sponge which picks up dirt and then does not release it. Once the sponge is too dirty to use, the dirty area can be cut off and discarded, leaving a clean surface. I used up several of these sponges throughout the project. On less delicate items I generally used the sponge at the start, as it was far more effective, while for more delicate items I used the brush or did not clean at all for fear of destroying the item. While working on most of the items I was able to employ a digital camera to document the condition both before and after cleaning. The first camera was not ideal as it ran on AA batteries and drained them quickly. It also had no auto-focus feature, and I am afraid that photography cannot be numbered among my talents. As such, the quality of the photos was somewhat lacking until the Rare Books librarian managed to secure a higher quality camera. Thereafter I was able to document the cleaning procedures more clearly. Once the volumes were evaluated and cleaned, I entered the vital information from the item into an Excel spreadsheet. Using this I was able to record each item’s title, author, publisher, and date. I was also able to make certain notes regarding the condition of each item. More importantly, I was able to check the availability of each item against cataloged State Library holdings, WorldCAT listings, and the commercial availability through Abebooks.com. In most cases, the items were not available from Abebooks, nor were they already listed in the State Library holdings. However, I was able to find the majority of the items in the collection listed at other libraries through WorldCAT, and from there I was able to evaluate the completeness of the State Library collection. It appears what while many libraries have individual items from the collection, no other library in the world has them all together the way the State Library of Pennsylvania does. The Future Currently, the Columbian Exposition Collection lives on a pair of book carts in the State Library. Several issues need to be addressed before they can be housed elsewhere. First, the volumes must either be re-covered or separated into their individual items, with each being stored in a separate holder. Additional, more detailed cleaning must take place in order to remove what dust is left on the pamphlets. The collection is currently in the cataloging queue, and must be added to the State Library catalogue. For the more delicate items, particularly the newspapers, further conservation efforts may be needed. Once these things have been done, however, the collection should be ready for permanent housing. The collection also represents an incredible opportunity for online exhibits. Many of the materials are beautifully illustrated and contain a fascinating look at the late 19 th century world, but are too delicate to allow for general display and use. Digitization would allow the collection to be displayed for the public and used by researchers yet remain in a controlled environment, which would help to preserve a truly unique collection for future use.