Diagnostic Challenge of Axonal Degeneration in Horses with

advertisement

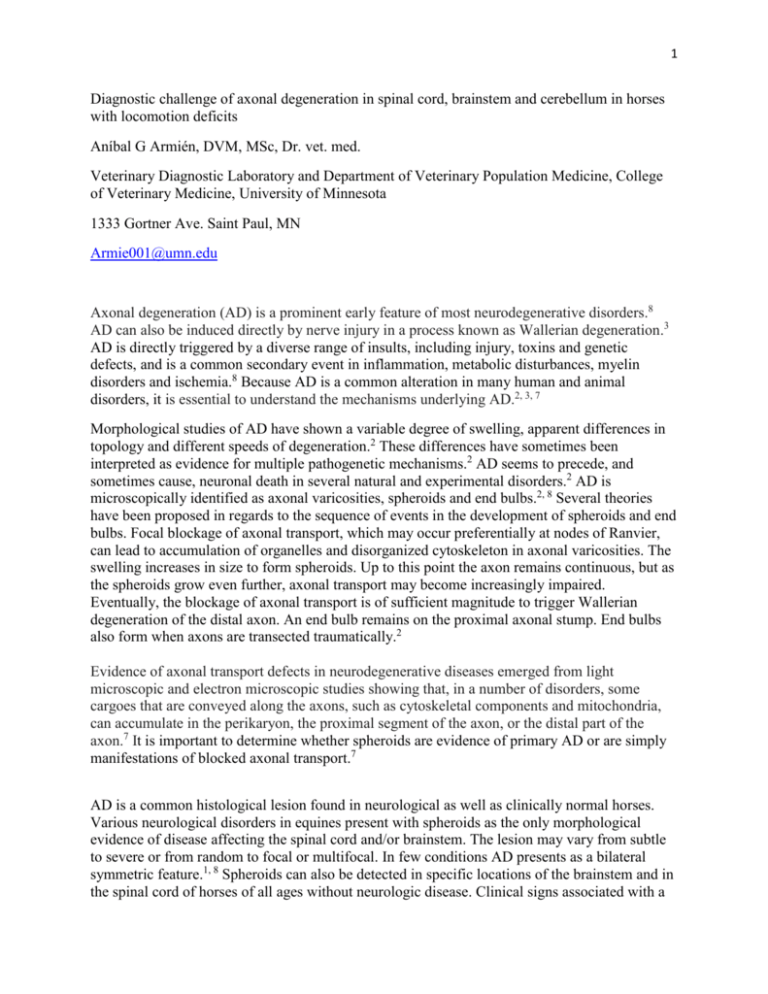

1 Diagnostic challenge of axonal degeneration in spinal cord, brainstem and cerebellum in horses with locomotion deficits Aníbal G Armién, DVM, MSc, Dr. vet. med. Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory and Department of Veterinary Population Medicine, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Minnesota 1333 Gortner Ave. Saint Paul, MN Armie001@umn.edu Axonal degeneration (AD) is a prominent early feature of most neurodegenerative disorders.8 AD can also be induced directly by nerve injury in a process known as Wallerian degeneration.3 AD is directly triggered by a diverse range of insults, including injury, toxins and genetic defects, and is a common secondary event in inflammation, metabolic disturbances, myelin disorders and ischemia.8 Because AD is a common alteration in many human and animal disorders, it is essential to understand the mechanisms underlying AD.2, 3, 7 Morphological studies of AD have shown a variable degree of swelling, apparent differences in topology and different speeds of degeneration.2 These differences have sometimes been interpreted as evidence for multiple pathogenetic mechanisms.2 AD seems to precede, and sometimes cause, neuronal death in several natural and experimental disorders.2 AD is microscopically identified as axonal varicosities, spheroids and end bulbs.2, 8 Several theories have been proposed in regards to the sequence of events in the development of spheroids and end bulbs. Focal blockage of axonal transport, which may occur preferentially at nodes of Ranvier, can lead to accumulation of organelles and disorganized cytoskeleton in axonal varicosities. The swelling increases in size to form spheroids. Up to this point the axon remains continuous, but as the spheroids grow even further, axonal transport may become increasingly impaired. Eventually, the blockage of axonal transport is of sufficient magnitude to trigger Wallerian degeneration of the distal axon. An end bulb remains on the proximal axonal stump. End bulbs also form when axons are transected traumatically.2 Evidence of axonal transport defects in neurodegenerative diseases emerged from light microscopic and electron microscopic studies showing that, in a number of disorders, some cargoes that are conveyed along the axons, such as cytoskeletal components and mitochondria, can accumulate in the perikaryon, the proximal segment of the axon, or the distal part of the axon.7 It is important to determine whether spheroids are evidence of primary AD or are simply manifestations of blocked axonal transport.7 AD is a common histological lesion found in neurological as well as clinically normal horses. Various neurological disorders in equines present with spheroids as the only morphological evidence of disease affecting the spinal cord and/or brainstem. The lesion may vary from subtle to severe or from random to focal or multifocal. In few conditions AD presents as a bilateral symmetric feature.1, 8 Spheroids can also be detected in specific locations of the brainstem and in the spinal cord of horses of all ages without neurologic disease. Clinical signs associated with a 2 number of spinal cord disease varies from subtle to severe paresis, ataxia, propioceptive deficits, abnormal postural reactions, nerve reflex abnormalities and muscle atrophy and abnormal muscle tone.8 Examples of disorders that present with AD include neuro-axonal dystrophy (NAD) and equine degenerative myelopathy (EDM), spinal cord compressions, and shivers. 1, 9 NAD is a bilaterally symmetric neuro-axonal degeneration of selected nuclei and axonal processes in the central nervous system (CNS). EDM is considered to be a more advanced form of NAD. Clinically, NAD and EDM are indistinguishable. Neurologic abnormalities consist of symmetric ataxia, dysmetria, conscious proprioceptive deficits, and weakness that typically develop during the 1st year of life in both entities. The etiology of NAD/EDM remains unknown. Both entities appear to have a strongly inheritable component. NAD/EDM have been associated with vitamin E deficiency. NAD/EDM are considered to be important differential diagnosis in cases of symmetric ataxia and paresis in young horses of any breed.1, 6 Compressive myelopathy has been reported in several species including horses. Cervical stenotic myelopathy (CSM, wobbler syndrome), which is one of the most common causes of compression of the spinal cord, is the result of malformations of the cervical vertebrae leading to stenosis of the vertebral canal. CSM typically affects young horses and has an increased incidence in certain breeds. Males seem to be more frequently affected than females with reported ratios ranging from 3:1 to 23:1. CSM is a multifactorial disease.8 Shivers, on the other hand, is a chronic, gradually progressive movement disorder that usually begins before the age of 7 years and has an increased prevalence in tall male horses. Clinically, horses with shivers have difficulty walking backwards, assume hyperflexed limb postures and have hind leg tremors during backward movement. Owner-reported additional clinical signs in confirmed cases include muscle twitching, muscle atrophy, reduced strength and exercise intolerance. No potential triggering factors or effective treatments are reported. Gross lesions are absent and no histologic lesions were hitherto identified in the nervous system.4, 5 It is important that focal to multifocal AD can also be found in toxic, parasitic or inflammatory diseases in horses. In horses, the vast majority of degenerative conditions require a combined approach of clinical and pathological examination methods to achieve a definitive diagnosis.1, 6 In a number of disease entities, the histopathologic examination is the gold standard of establishing a final diagnosis such as in the case of NAD/EDM.1, 6 However unfortunately, the causes of a large number of degenerative disorders that present with subtle and random AD remain inconclusive after examination of histological preparations. Under diagnostic conditions during the spinal cord may be suboptimally preserved, occasionally collected only casually, and the number of histologically examined sections may be inadequate. Therefore the distribution of the axonal lesion is frequently incompletely mapped. Furthermore, it is in any given case often difficult to associate the lesion distribution with the clinical signs and even more difficult to associate the lesion with a specific causative entity. Histological differentiation of NAD/EDM from other degenerative conditions, such as compressive myelopathy and shivers is difficult, since gross abnormalities are usually absent and microscopic secondary lesions are frequently superimposed. 3 Thus, a systematic approach of gross, histological, immunohistochemical, electron microscopic and functional anatomical analysis ideally in combination with a thorough clinical neurologic work up is required to narrow the differential diagnoses. The review of spinal cord degenerative disease of equines and the discussion of a methodology applied in our laboratory in a diagnostic and a research setting, in which we have studied horses with locomotion deficit that present with AD in spinal cord, brainstem and cerebellum is the topic of this presentation. The discussion emphasizes a systematic evaluation of cases of NAD/EDM, and shivers. Preliminary results are presented in the Table #1. Table 1. Distribution of axonal degeneration in neuro-axonal dystrophy/equine degenerative myelopathy and shivers compared to compressive myelopathies and controls. Intermediary column Clark column +++/+ - ++/+ - +/+/+ (+) + +++/+ ++/+ (+) + +/+/- +/+ ++/(+) +++/+ +/++/(+) + +/- +/- +/- +/- +/- +/- +/- Nerves Cuneate nuclei + + + White mater degeneration Reticular formation (brainstem) Nervous system lesions Vestibular nuclei Control Shivers EDM Spinal cord compressions Others Neurological sings Cerebellar nuclei Conditions +/+/- 1. Aleman M, Finno CJ, Higgins RJ, Puschner B, et al. Evaluation of epidemiological, clinical, and pathological features of neuroaxonal dystrophy in Quarter Horses. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2011; 239(6):823-33. 2. Coleman M. Axon degeneration mechanisms: commonality amid diversity. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2005; 6 (11): 889-898, 3. Conforti L, Gilley J, and Coleman MP. Wallerian degeneration: an emerging axon death pathway linking injury and disease. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2014; 15(6):395-409. 4. Draper AC, Bender JB, Firshman AM, et al.. Epidemiology of shivering (shivers) in horses. Equine Vet J. 2014; May 6. doi: 10.1111/evj.12296 [Epub ahead of print] 4 5. Draper AC, Trumble TN, Firshman AM, Baird JD, Reed S, Mayhew IG, Mackay R, Valberg SJ. Posture and movement characteristics of forward and backward walking in horses with shivering and acquired bilateral stringhalt. Equine Vet J. 2014; Mar 10. doi: 10.1111/evj.12259. [Epub ahead of print] 6. Finno CJ, Higgins RJ, Aleman M, Ofri R, Hollingsworth SR, Bannasch DL, Reilly CM, Madigan JE. Equine degenerative myeloencephalopathy in Lusitano horses. J Vet Intern Med. 2011; 25(6):1439-46. 7. Millecamps S and Julie J-P. Axonal transport deficits and neurodegenerative diseases. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2013; 14(3):161-176, 8. Summer BA, Cumming JF, De Lahunta, A. Veterinary Neuropathology. New York, Mosby, 527 pg. 1995 9. Valberg SJ, Lewis, SS, Shivers JL, et al. The equine movement disorder “Shivers” is associated with selective cerebellar Purkinje cell axonal degeneration. Vet. Pathol. under review