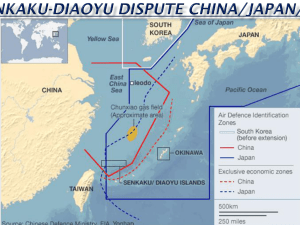

"Much Ado Over Small Islands: The Sino-Japanese

advertisement