The Roaring Twenties: Social and Technological Changes

advertisement

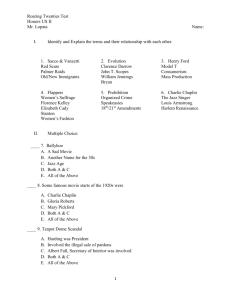

Name________________________________ Date____________ Periods: _____ Day: _______ United States History & Government 11 The Roaring Twenties The Roaring Twenties: Social and Technological Changes In the 1920’s, there were many technological and social changes occurring. A new kind of woman was emerging: the flapper. She wore new clothing styles, bobbed her hair and drove fast cars. “Is the ‘old-fashioned girl’, with all she stands for in sweetness, modesty and innocence, in danger of becoming extinct?” wondered one magazine in 1921. The invention of radio and movies, along with newspapers, created heroes and heroines known across the country. Some of the best loved heroes of the 1920s were athletes, and the most popular was Babe Ruth. But the greatest hero of the decade was an aviator named Charles Lindbergh. Also during the 1920’s, a new type of music called jazz was developed by brilliant and young musicians like Louis Armstrong, Bessie Smith and Duke Ellington. This new form of music swept the U.S. and spread quickly around the world. The development of jazz, and a movement of black writers like Langston Hughes celebrating their African American heritage while protesting prejudice and racism led to the Harlem Renaissance in New York. 1. Why do you think so many young people enjoyed the changes of the 1920’s?______________________ ______________________________________________________________________________________ 2. Based on the above reading, complete the webs below. People that changed the 1920's Inventions that changed the 1920's People How did this person affect change in the 1920’s? Flappers Langston Hughes Louis Armstrong Charles Lindbergh Babe Ruth Inventions Automobile Radio Motion Pictures (movies) Jazz How did this invention affect change in the 1920’s? THE FLAPPER Flappers were young women who rebelled against traditional ways of thinking and acting. Flappers wore "kiss proof" lipstick and a lot of heavy makeup with beaded necklaces and bracelets. They liked to cut their hair into "boyish" bobs, often dyeing it jet-black. Flapper dresses were straight and loose, leaving the arms bare and dropping the waistline to the hips. To many older Americans, the way flappers behaved was even more shocking than the way they looked. Flappers went to jazz clubs at night where they danced all night, smoked cigarettes long holders, and dated. They rode bicycles and drove cars. They drank bootleg alcohol openly in speak easies, a defiant act in the period of Prohibition. Only a few young women were flappers. Still, they set a style for others. Slowly, older women began to cut their hair and war makeup and shorter skirts. For many Americans, the bold fashions pioneered by the flappers symbolized a new sense of freedom. THE AUTOMOBILE By the late 1920s, the automobile had firmly established itself as the newest and most popular method of road transport. The rapidly growing automobile industry led by Henry Ford and the Ford Motor Company produced new and better models every year for the insatiable public demand. Increased wages and lower cost vehicles through mass production made cars increasingly affordable, although 3 out of 4 cars were bought on installment plans. Roads that had been designed for horse transport began to deteriorate under the steadily increasing load of traffic. In 1906 local governments supplied 96 percent of the road funding. In 1927 the State governments supplied about 37 percent, the Federal Government 10 percent, and the local governments 53 percent. Roads (including wooden roads) had to be redesigned and rebuilt to accommodate the automobile, new road rules had to be introduced, standardized road signs erected, and methods of controlling traffic (like traffic lights) implemented in densely populated areas. Vehicles required much higher road clearances than modern cars due to the poor state of roads and tracks, hence the large diameter skinny tires of the day which were effective at cutting through mud to reach more solid ground. The car enabled people to travel much further than foot or horse had permitted. Touring vacations became popular, but motorists had to plan carefully as there were often long distances between petrol stations and breakdowns were fairly common. Tourist parks (Motels) and other facilities sprang up to service the needs of traveling motorists. Petrol station chains cashed in on the trend by supplying maps that highlighted their business locations, and then sold travelers food and drink as well as petrol and oil. THE RADIO The radio enabled listeners to experience an event as it happened. Rather than read about Lindbergh meeting President Coolidge after his flight to Paris, people witnessed it with their ears and imaginations. The radio, which knew no geographic boundaries, drew people together as never before. Soon, people wanted more of everything—music, talk, advice, drama. They wanted bigger and more powerful sets, and they wanted greater sound fidelity. By the end of 1923, an estimated 400,000 households had a radio, a jump from 60,000 just the year before. Overnight, it seemed, everyone went into broadcasting: newspapers, banks, public utilities, department stores, universities and colleges, cities and towns, pharmacies, creameries, and hospitals, among others. In the beginning people’s awe at hearing sounds through the air was so great they would listen to almost anything. The broadcasters decided to give them a mix of culture, education, information, and some entertainment. Typical of the programming were the offerings of station WJZ, which began regular broadcasting in New York at 3:00 PM on May 16, 1923: 3:00 Violet Pearch, pianist 3:30 Things to tell the Housewife about cooking meat 3:45 Elsa Rieffin, soprano 4:00 Home—Its Equipment, by Ada Swan 4:15 Rinaldo Sidoli, violinist 4:30 Ballad of Reading Gaol, part 1, by Mrs. Marion Leland 5:00 Ballad of Reading Gaol, part 2, by Mrs. Marion Leland 5:15 Rinaldo Sidoli, violinist 5:30 Rea Stelle, contralto 6:00 Peter’s Adventures, by Florence Vincent 7:30 Frederick Taggart, baritone 8:15 Lecture by W. F. Hickernell 8:45 Salvation Army band concert 9:15 Viola K. Miller, soprano 9:30 Salvation Army Band,Male Chorus 10:00 Concert So it went day after day. That year WJY, another New York station, would present 98 baritone solos, 6 baseball games, 5 boxing bouts, 67 church services, 7 football games, 10 harmonica solos, 74 organ concerts, 340 soprano recitals, 40 plays, 723 talks and lectures, and 205 bedtime stories. MOTION PICTURES (MOVIES) The film industry really bloomed in the 1920’s. The movies of this time were being made at the first 20 Hollywood studios. The films of the 1920's were in major demand during this era. Most of the productions were all silent but theaters were packed every night. "The Big Five" movie studies consisted of Warner Brothers Pictures, MGM, RKO (Radio-KeithOrpheum) Pictures, Famous Players-Lasky (later Paramount), and Fox Film Corporation. Three smaller, minor studios were dubbed "The Little Three". Universal Pictures, United Artists, and Columbia Pictures. In 1916 there were 21,000 movie theaters in the United States. The number of people who attended movies doubled in the last half of the 1920s. Movies in the 1920s were seen to be as influential as television is today. In 1928 a series of 12 studies were made on the impact of movies on children. These studies noted the “influence of the screen upon manners, dress, codes and matters of romance.” Movies definitely had the potential and did influence and effect the way people acted and thought. One of the greatest comedians of all times was Charlie Chaplin. He was most famous for his participation in comedic silent films at this time. JAZZ Born in New Orleans, jazz combined West African rhythms, African American work songs and spirituals, and European harmonies. Jazz also had roots in the ragtime rhythms of composers like Scott Joplin. Jazz quickly spread from New Orleans to Chicago, Kansas City, and the African American section of New York known as Harlem. By the mid-1920s, jazz was being played in dance halls and roadhouses and speakeasies all over the country. White musicians also began to adopt the new style. Before long, the popularity of jazz spread to Europe as well. Many older Americans worried that jazz and the new dances that accompanied it were a bad influence on the nation’s young people. Despite their complaints, jazz continued to grow more popular. LANGSTON HUGHES: POET OF THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE Probably the best known poet of the Harlem Renaissance was Langston Hughes. He published his first poem, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers”, soon after graduating from high school. The poem connected the experiences of black Americans living along the Mississippi River with those of ancient Africans living along the Nile and Niger rivers. Like other writers of the Harlem Renaissance, Hughes encouraged African Americans to be proud of their heritage. I've known rivers: I've known rivers ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood in human veins. My soul has grown deep like the rivers. I bathed in the Euphrates when dawns were young. I built my hut near the Congo and it lulled me to sleep. I looked upon the Nile and raised the pyramids above it. I heard the singing of the Mississippi when Abe Lincoln went down to New Orleans, and I've seen its muddy bosom turn all golden in the sunset. I've known rivers: Ancient, dusky rivers. My soul has grown deep like the rivers. In other poems, Hughes protested racism and acts of violence against African Americans. In addition to his poems, Hughes wrote plays, short stories, and essays about the black experience. One of Hughes’ most famous poems is titled “I, too.” I, too, sing America. I am the darker brother. They send me to eat in the kitchen When company comes, But I laugh, And eat well, And grow strong. Tomorrow, I'll be at the table When company comes. Nobody'll dare Say to me, "Eat in the kitchen," Then. Besides, They'll see how beautiful I am And be ashamed— I, too, am America. Louis Armstrong: The Father of Jazz Louis Armstrong, the Great Satchmo, was one of the brilliant young African American musicians who helped create jazz. Armstrong learned to play the trumpet in the New Orleans orphanage where he grew up. Armstrong had the ability to take a simple melody and experiment with the notes and the rhythm. This allowed listeners to hear many different versions of the basic tune. In the 1920s, Armstrong performed with a number of different musical groups, and began to revolutionize the jazz world with his introduction of the extended solo. Prior to his arrival, jazz music was played either in highly orchestrated arrangements or in a more loosely structured "Dixieland"-type ensemble in which no one musician soloed for any extended period. Musicians everywhere soon began to imitate his style, and Armstrong himself became a star attraction. His popularity was phenomenal, and throughout the 1920s he was one of the most sought-after musicians in both New York and Chicago. Armstrong's HOT FIVE and HOT SEVEN recordings remain to this day some of the best loved of the time. Scat singing is vocalizing either wordlessly or with nonsense words and syllables (e.g. "Skiddo bop bap") as employed by jazz singers who create the equivalent of an instrumental solo using only the voice. Also it is a type of voice instrumental. A frequently repeated legend alleges that Louis Armstrong invented scat singing on the spot when he dropped the lyric sheet while singing during his recording of "Heebie Jeebies" in 1926. The story is false and Armstrong himself made no such claim. However, the record "Heebie Jeebies" and subsequent Armstrong recordings introduced scat singing to a wider audience and did much to popularize the style. Armstrong was an innovative singer who experimented with all kinds of sound and improvised with his voice as well as on his instrument. In one famous example, Armstrong scatted a passage on "I'm a Ding Dong Daddy from Dumas"—he sings "I've done forgot the words!" in the middle of recording before taking off in scat. CHARLES LINDBERGH Arguably the greatest hero of the 1920s was Charles A. Lindbergh, also known as Lucky Lindy. On a gray morning in May 1927, he took off from an airport in New York to fly nonstop across the Atlantic Ocean— alone. For more than 33 hours, Lindbergh piloted his tiny single-engine airplane, the Spirit of St. Louis, over the stormy Atlantic. He carried no map, no parachute, and no radio. At last, he landed in Paris, France. The cheering crowd carried him across the airfield. Lucky Lindy returned to the U.S. as the hero of the decade. He said “I’ve broken the world’s distance record for a non-stop airplane flight…The Spirit of St. Louis is a wonderful plane. It’s like a living creature, gliding along smoothly, happily as though a successful flight means as much to it as to me, as though we shared our experiences together, each feeling beauty, life and death….each dependent on the other’s loyalty. We have made this flight across the ocean, not I or it.” Lindbergh Does It! To Paris in 33 1/2 Hours; Flies 1,000 Miles Through Snow and Sleet; Cheering French Carry Him Off Field New York Times, May 21, 1927 Early in the morning on May 20, 1927 Charles A. Lindbergh took off in The Spirit of St. Louis from Roosevelt Field near New York City. Flying northeast along the coast, he was sighted later in the day flying over Nova Scotia and Newfoundland. From St. Johns, Newfoundland, he headed out over the Atlantic, using only a magnetic compass, his airspeed indicator, and luck to navigate toward Ireland. The flight had captured the imagination of the American public like few events in history. Citizens waited nervously by their radios, listening for news of the flight. When Lindbergh was seen crossing the Irish coast, the world cheered and eagerly anticipated his arrival in Paris. A frenzied crowd of more than 100,000 people gathered at Le Bourget Field to greet him. When he landed, less than 34 hours after his departure from New York, Lindbergh became the first person to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean. BABE RUTH “The only real game in the world, I think, is baseball.” “Every strike brings me closer to the next home run.” Some of the best-loved heroes of the 1920s were athletes. Baseball was America’s real passion. The most popular player of the 1920s was Babe Ruth. He became the star of the New York Yankees. Fans flocked to see the “Sultan of Swat” hit home runs. The 60 home runs he hit in one season (1927) set a record that lasted more than 30 years. His lifetime record of 714 home runs was not broken until 1974. Up until “The Great Bambino”, baseball had been dominated by pitchers, a game of defense that was most satisfying when the score was low; after him, it was all offense, a hitter’s game that was at its most thrilling when someone (usually Ruth) but a bat to leather and delivered a souvenir to the fans sitting behind the outfield fence. In 1920, Red Sox owner Harry Frazee sold Ruth to the New York Yankees. The transaction spawned the Curse of the Bambino. Over his next 15 seasons in New York, Ruth led the league or placed in the top ten in batting average, slugging percentage, runs, total bases, home runs, RBI, and walks several times. Ruth hit 60 home runs in 1927. It stood as the single season home run record for 34 years. The people who saw the “Sultan of Swat” hit a home run in the 1920s felt as special as people from later generations watching a rocket launch.