Bhavnani-Drake-Peru

advertisement

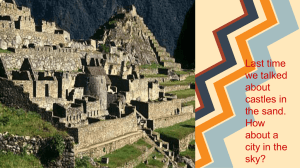

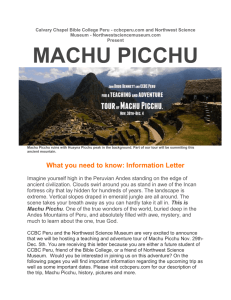

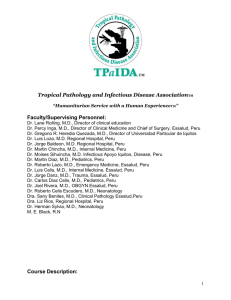

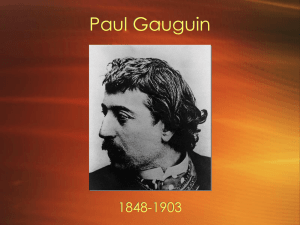

DIVA Team Awarded Grants to Study Neglected Infectious Diseases “Tropical diseases such as Rickettsioses and Leishmaniases have ravaged ancient cultures, but surprisingly are still virulent not only in the developing world, but also increasingly in the developed world” says Dr. Bhavnani, Associate Professor, and PI of the Discovery and Innovation through Visual Analytics (DIVA) Lab in the ITS. We spoke with Dr. Bhavnani and his PhD student Justin Drake who both visited Peru after receiving grants to study neglected infectious diseases in tropical countries. What is the nature of the grants that you both received? Bhavnani: We received a pilot grant from the Justin Drake (PhD student), and Dr. Bhavnani at Machu Picchu, Institute of Human Infections and Immunity here Peru, on a research trip to explore collaborations related to at UTMB to study Rickettsioses, a class of neglected tropical diseases. diseases that is typically transmitted through the bite of infected ticks. In collaboration with Co-I Dr. Juan Olano, a physican and expert in Rickettsioses, we will be using visual analytical technologies developed in the DIVA Lab to analyze biomarkers related to specific forms of this disease. For example, we will be analyzing Mediterranean Spotted Fever, a systemic form of Rickettsioses, which can result in severe damage to the endothelial cells that line blood vessels, causing plasma to leak out of the blood vessels resulting in high morbidity and mortality. Also partially funded by the grant is Justin Drake (PhD student co-mentored by myself and Dr. Brasier), and Bryant Dang, a research associate in the DIVA Lab. Drake: I received the Student Government Travel Grant for Graduate School Organization Members, and the Graduate School for Biomedical Sciences Travel Grant. These grants were to visit Peru and transmit my research experience to graduate students at UTMB. Last week I received the University Federal Credit Union Scholarship Award, which will fund my continued research in infectious diseases. Why did you visit Peru, and what did your trip achieve? Bhavnani: Peru has a well-established research infrastructure for studying a wide range of tropical diseases. For example, the US Naval Medical Research Unit-6 (NAMRU-6) in Lima performs translational research related to tropical infectious diseases affecting uniformed service members and the general population in Peru and throughout Central and South America. Because UTMB has strong links with NAMRU-6, we thought it was a good starting point for our research. Hosted by Dr. and Lieutenant Colonel Eric Halsey head of the Virology Department at NAMRU-6, we gave a presentation of visual analytics to biologists and infectious disease researchers. The presentations led to discussions of sharing samples related to Ricketssioses collected in Peru, and its analysis using visual analytics. These face-to-face encounters were invaluable for us to understand the context and culture in which the research is being conducted in Peru. We have also been invited to visit with Dr. Halsey the Amazon rain forest where many tropical diseases originate. Furthermore, we visited Cusco where we met Dr. Miguel Cabada, a former graduate student at UTMB, who has started a research lab to analyze human samples such as from Fluke patients. He invited us to visit a government, and a private hospital to understand the differences in resources and treatments. The visit led to discussions of collaborations related to research and teaching at the local university. Drake: I was particularly struck by the stark differences in facilities and care between the government run hospital in Cusco, and the adjoining private hospital catering mainly to visitors. From Dr. Cabada, I also learned the huge hurdles he has faced related to setting up a new research unit in a Burial clay artifact of a woman with Leshmianses developing country. While I did observe such disparities and from the Moche period predating the Incas. hurdles during my visit as an undergraduate student to China Photograph: Courtesy Museo Larco, Lima, Peru. and India, my visit to Peru as a PhD student made these experiences especially vivid because of their relevance to my dissertation topic. Another strong experience was travelling with Dr. Bhavnani, who engaged and challenged me in discussions ranging from research to art and culture related to tropical diseases. As these discussions occurred in real time, and in the context of different encounters, they were filled with concrete details that helped me appreciate the complex interplay of multiple dimensions. For example, we visited Museo Larco in Lima where we viewed and discussed an ancient clay burial artifact predating the Incas of a patient suffering from Leishmaniases, a disfiguring disease caused by a bacterium that is virulent even today. Finally, visiting Machu Picchu was a fantastic archeological experience, especially because our trip to the site at 9000 feet above sea level occurred on a perfect sunny day so we could take 3D, and GPS tagged photographs. These experiences were invaluable and unforgettable. Oh, another thing … in sharp contrast to his meticulous research, I noticed how absent-minded Dr. Bhavnani can be – we had a scary moment when he could not find where he had put his immigration papers! What insights did you have regarding translational science? Bhavnani: A common theme that we experienced throughout our discussions with the different researchers in Peru was a need for an intuitive understanding of complex relationships in infectious disease data. Visual analytics could therefore play a vital role in helping to decipher the molecular nature of infectious diseases, with the goal of translating those insights into contextually relevant therapeutics. Another insight came from our visit to Machu Picchu. It appears that the Incas at Machu Picchu had explored a broad vision of what we call translational science. Archaeologists believe that Machu Picchu was the site of many basic experiments such as growing the same crop at different elevations created by the platforms cut into the mountain, redirecting and progressively filtering mountain streams to create potable water, and measuring precisely astronomical events at different times of the year to predict optimal times for sowing and harvest. The results from the Machu Picchu “lab” were then translated to the general population for improving daily lives. The notion of translation therefore appears to have incorporated a wide range disciplines such as agriculture, civil engineering, and astronomy. Perhaps in time, we can re-discover how other important dimensions besides biology and clinical variables intersect to improve health outcomes.