Spring 2010

advertisement

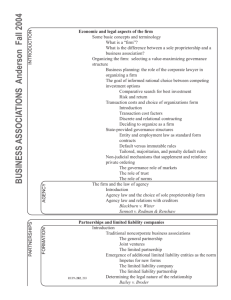

1 Business Associations Professor Bradford Spring 2010 Exam Answer Outline The following answer outlines are not intended to be model answers, nor are they intended to include every issue students discussed. They merely attempt to identify the major issues in each question and some of the problems or questions arising under each issue. They should provide a pretty good idea of the kinds of things I was looking for. If you have any questions about the exam or your performance on the exam, feel free to contact me to talk about it. I graded each question separately. Those grades appear on your printed exam. To determine your overall average, each question was then weighted in accordance with the time allocated to that question. The following distribution will give you some idea how you did in comparison to the rest of the class: Question 1: Question 2: Question 3: Question 4: Question 5: Question 6: Question 7: Question 8: Range 0-8; Average = 4.19 Range 3-9; Average = 5.89 Range 0-8; Average = 6.19 Range 0-9; Average = 5.19 Range 3-8; Average = 5.81 Range 0-9; Average = 5.70 Range 3-9; Average = 6.07 Range 2-9; Average = 5.26 Total (of unadjusted exam scores, not final grades): Range 3.86-7.30; Average = 6.19 2 Question 1 The court will dismiss Tom’s derivative action. Under Delaware law, a plaintiff in a shareholders’ derivative action must plead either that he made demand on the board or why demand was excused. Demand is excused only if the plaintiff alleges particularized facts that either (1) the directors are not disinterested and independent or (2) the transaction was not otherwise the product of a valid business judgment because it violated either procedural or substantive due care. Aronson v. Lewis (discussed in Marx v. Akers). Demand is not excused merely because all the directors are named as defendants. Marx v. Akers. The first allegation is insufficient. The second allegation is also insufficient. Failure to inform would be a violation of the duty of care and would show that the transaction was not otherwise the product of a valid business judgment. However, there must be allegations of particularized facts that support that conclusion. Marx v. Akers. A general allegation that the directors violated the duty to inform is insufficient. The allegation about Barry Boss is a sufficient allegation that Boss is not disinterested. However, demand is excused only if the plaintiff alleges a defect as to a majority of the directors. Marx v. Akers. The allegation that Boss controls the other four directors is conclusory; there are no particularized facts indicating the other directors lack independence. 3 Question 2 The statement about an investor’s right to withdraw is technically correct, but misleading. A partner in a general partnership has the right to dissociate at any time. RUPA § 602(a). That right may not be taken away by agreement; the partnership agreement may only require that the notice be in writing. RUPA § 103(b)(6). However, that does not necessarily mean that the general partnership has no continuity. Although partners have a right to withdraw, that withdrawal may be wrongful and subject them to liability for damages. A partner’s dissociation is wrongful if it is in breach of an express provision of the agreement or, in most cases, before the expiration of the term or undertaking which the agreement provides for. RUPA § 602(b)((1),(2). Partners are liable to the other partners for damages for wrongful dissociation. RUPA § 602(c). And, if the partners have agreed to a specific term of existence, whether expressed as a period of time or completion of a particular undertaking, a partner’s dissociation does not usually dissolve the business. See RUPA § 801(2). The business continues in spite of the wrongfully dissociating partner’s withdrawal. In addition, a partner’s dissociation does not necessarily deprive the business of the capital contributed by that partner or the value of that partner’s interest. When dissociation is wrongful, the departing partner is not entitled to a buyout until the expiration of the specified term or undertaking. RUPA § 701(h), unless the dissociating partner can show that earlier payment will not cause “undue hardship to the business.” Id. Thus, although a partner does have a right to withdraw, the business does not usually lose capital as a result of that withdrawal and any loss of the departing partner’s human capital can be recovered in the form of damages. Moreover, these financial penalties make it less likely that partners will wrongfully dissociate in the first place. 4 Question 3 Dana has possible liability under two provisions of federal securities law: (1) Section 16(b) of the Exchange Act; and (2) Rule 10b-5, adopted pursuant to section 10(b) of the Exchange Act. Section 16(b) Section 16(b) imposes liability on three categories of defendants: officers, directors, and 10% beneficial owners. See Exchange Act §§ 16(a),(b). Dana must have fallen into one of these categories immediately prior to the transaction for it to be covered by section 16(b). See Reliance Electric v. Emerson Electric. Dana was a director at all relevant times, so all of her trading here is covered by § 16(b). Section 16(b) applies to any class of equity security registered pursuant to section 12 of the Exchange Act. See §§ 16(a),(b). Image’s common stock is covered, because it’s an equity security and it’s registered pursuant to section 12. Dana is liable under section 16(b) if she purchased and sold the stock within any period of less than six months for a profit. Liability under § 16(b) does not depend on the misuse of confidential, nonpublic information, so Dana’s use of the information from Sam is irrelevant for § 16(b) purposes. Image’s initial purchase on January 3 was within six months of her sale on June 5. Therefore, she’s liable for her profit on the 30,000 shares sold on June 5. The profit would be 30,000 shares x ($30 - $20) = $300,000. Dana is not liable for profit on her sale on August 1. That is more than six months after the initial purchase, so there’s no matching purchase within six months of the August 1 sale. Rule 10b-5 Dana may also be liable for insider trading in violation of Rule 10b-5. Dana clearly traded on the basis of material, nonpublic information; however, for that to create liability under Rule 10b-5, Dana’s trading without disclosure of the information must breach a fiduciary duty. Chiarella. Otherwise, the deceit required for liability under Rule 10b-5 is not present. Liability as a classical insider Dana is a classical insider. She owes a fiduciary duty to Image because she’s a director. However, unlike the situation in Texas Gulf Sulphur, Dana is not using information acquired from Image in breach of that duty. The information came from outside Image and her status as a director had nothing to do with it. Thus, arguably, her use of that information does not breach a duty of confidentiality owed to Image. However, one might argue that, as a director, she owes a duty of disclosure to Image with 5 respect to any relevant information she acquires about the company, no matter the source. Then, if she traded on the basis of that information without disclosing it to Image, she could be liable. See O’Hagan. The argument for such a duty would be buttressed if Sam provided the information to her only because of her status as a director of Image. Liability as a tippee Dana might also be liable as a tippee of someone who owes a fiduciary duty. Sam agreed with Steve Jobs not to disclose the information until the March 1 publication date. This agreement is sufficient to establish a duty of confidence under Rule 10b5-2(b)(1). Sam breached this agreement by telling Dana, so Dana might be liable as Sam’s tippee under Dirks. For such liability to exist, Sam must have breached his duty for personal gain. Sam did not directly gain by telling Dana. She is his friend, and Dirks says a gift can constitute a personal gain to the tipper. But, although Sam and Dana are friends, it’s not clear Sam is providing this information so Dana can make money through trading. He’s apparently just telling her because she’s a director of Image. Even if Sam revealed the confidence for personal gain, Dana is liable only if she knew or should have known Sam breached a duty when he disclosed the information. Dirks. It’s not enough that she know the information was confidential; she must know that Sam is breaching his duty in revealing the information. She doesn’t know that Sam agreed to keep the information confidential, so the question is whether she should have known. She knew the information was nonpublic and she knew it came from Steve Jobs. Should she have known that Steve Jobs would not provide it to Sam without a promise of confidentiality? Or, since Sam is a reporter, would it be reasonable for her to assume that Steve Jobs did not expect Sam to keep the information confidential? Liability for breach of a duty to Sam Dana could also be liable if she breached a duty of confidentiality she owed to Sam. O’Hagan. However, she never agreed not to use the information. Thus, she would owe a duty to Sam not to disclose only if they had a history of sharing confidences that would let her know Sam expected this to be kept confidential. Rule 10b5-2(b)(2). Nothing in the facts indicates any such history. 6 Question 4 The internal affairs rule is a choice-of-law rule. It provides that the law of the state of incorporation (or organization, in the case of a non-corporate entity) governs the internal affairs of the corporation (or other entity)—no matter the location of the company’s investors or its operations or where the lawsuit is brought. The internal affairs rule relates only to matters of internal affairs—such as the duties of officers and directors, governance of the corporation, and shareholder rights and powers. It does not affect external questions outside of corporate law, such as tort or contract liability. 7 Question 5 Duty of Loyalty This decision does not appear to violate the directors’ duty of loyalty. None of the directors was a party to the transaction or had a financial interest in the transaction that would make this self-dealing. See MBCA § 8.60(1). Fernando was not involved in creating the league, so he has no direct financial interest. His personal interest in volleyball is not a financial interest of the time the duty of loyalty is concerned with. Since this is not a director’s conflicting interest transaction, it is not subject to challenge on self-dealing grounds. MBCA § 8.61(a). Fernando’s push for Mega to purchase a team is probably motivated as much by his devotion to volleyball as by his interest in making money. However, his personal motivation for approving the purchase is probably irrelevant under Sinclair v. Levien, as long as the decision otherwise meets the directors’ duties. Good Faith Another aspect of the duty of loyalty is the obligation of directors to act in good faith. MBCA § 8.31(a)(2)(i). However, this does not appear to violate that obligation. The obligation of good faith is violated in two ways. Walt Disney Company Derivative Litigation. First, it’s a violation of good faith to intentionally harm the corporation. There’s nothing of that sort here. Second, it’s a violation of the obligation of good faith to consciously disregard one’s duties to the corporation. But this requires a knowing and complete failure of the directors to undertake their responsibilities, not just a bad or even grossly negligent decision. Lyondell Chemical Co. v. Ryan. The directors here analyzed the opportunity before approving the purchase. It might not be a good decision, but they did not totally neglect their duties. Duty of Care Procedural due care: the duty to inform The duty of care has two aspects, one procedural and one substantive. First, the directors must adequately inform themselves before making a decision. MBCA § 8.31(a)(2)(ii)(B); Smith v. Van Gorkom. The standard is gross negligence. Smith v. Van Gorkom. The directors here don’t appear to have been grossly negligent in informing themselves. They listened to a lengthy presentation by the organizers of the volleyball league and they also considered financial projections prepared by Mega’s finance department. Moreover, the question indicates a “lengthy discussion” by the directors before the decision was made. 8 Substantive due care: corporate waste The directors’ substantive decisions are protected by the business judgment rule. A decision that does not involve a conflict of interest will be overturned on substantive grounds only if it is a no-win transaction, sometimes called corporate waste. Essentially, this means a decision for which there is no plausible case that it’s in the best interests of the company. See Joy v. North; MBCA § 8.31(a)(2)(ii)(A). This transaction does not appear to fall into that category. Financial analysts have not reacted positively to the investment in PVL teams, but Mega’s own study indicates that it could be profitable. One analyst says risk-free government bonds might be more profitable (and obviously less risky). If this were unquestionably true, this might be a nowin transaction: the corporation would be getting a riskier, lower return than the risk-free alternative. But this is merely one person’s forecast and the board is not required to accept this forecast. Mega’s internal report predicts a possible 5-10 percent return, with the risk of some loss. Under the business judgment rule, it’s up to the board to weigh the possibilities and, as long as there’s a plausible claim that the decision is in the best interests of the company, the court will not second-guess the board’s judgment. This seems within the range of a reasonable business judgment, so the board will not be liable for a breach of the duty of care. 9 Question 6 Preemptive rights give an existing shareholder the right to purchase additional stock when the corporation issues new stock. The second transaction does not trigger preemptive rights; Small is repurchasing shares and preemptive rights apply only when Small is selling shares. However, Small is issuing shares in the first transaction, which triggers Calvin’s preemptive rights. Since the articles grant preemptive rights to Calvin, he has an option to purchase the shares offered to Ned in proportion to Calvin’s ownership of Small stock. See MBCA § 6.30(b)(1). However, this is an option on Calvin’s part. He has the right to purchase the shares, but is not obligated to, if he doesn’t want to. Since Calvin currently owns 1/10 of the outstanding shares, he is entitled to purchase 1/10 of the 200 new shares Small is issuing, or 20 shares. The terms of the purchase will be the same as those offered to Ned, $600 a share. See MBCA § 6.30(b)(1). Thus, Calvin may buy 20 of the 200 shares Small is issuing, for a total price of $12,000. 10 Question 7 A member of a LLC does not have authority to act on behalf of the LLC merely by virtue of being a member. RULLCA § 301(a). Instead of specifying when action on behalf of an LLC binds the LLC, the RULLCA defers to principles outside the Act, i.e., agency law. RULLCA § 301(b). Under general principles of agency law, La Comida is liable on the lease only if Arnie had some type of authority to sign it on behalf of La Comida. That authority may be actual, apparent, or implied. RSA § 140. It is not clear if Arnie had actual authority to sign the bowling alley lease. The operating agreement authorized him to lease a building for a restaurant, but not for a bowling alley. See ¶ 3 of the operating agreement. The members’ action at the March 1 meeting raises two issues: (1) did their action validly authorize La Comida to operate a bowling alley; and (2) if so, did that also authorize Arnie to lease the bowling alley. In a member-managed LLC, matters arising in the ordinary course of business are decided by majority vote. RULLCA § 407(b)(3). Matters arising outside the ordinary course of business must be decided unanimously. RULLCA § 407(b)(4). Unanimity is also required to amend the operating agreement. RULLCA § 407(b)(5). Operation of a bowling alley does not require an amendment of the operating agreement, as the operating agreement itself allows the LLC to engage in other business, provided the members approve it. The question is whether the decision to operate a bowling alley is in the ordinary course of business. The operating agreement authorizes the LLC to operate a restaurant, and leasing a bowling alley is probably not in the ordinary course of business for a restaurant. However, the agreement also authorizes “any other lawful business” authorized by the members. But does this make everything part of the ordinary course of the partnership’s business, thereby requiring only a majority vote, or does this still contemplate the statutory default rule of unanimity to add other business? The agreement is ambiguous. If the 3-2 vote was sufficient to authorize operating a bowling alley, it’s still not clear that Arnie was authorized to lease it. The operating agreement only gave him the authority to lease a restaurant, and the members on March 1 did not specifically authorize him to lease anything else. Is there enough in that vote, reasonably interpreted, to cause Arnie to believe that he was authorized to lease the bowling alley? See RSA § 26. Perhaps. Arnie could argue that he was already authorized to lease the restaurant and, when they voted to change the business of the LLC to operating a bowling alley and said nothing more, it was reasonable to believe that the authorization to lease automatically transferred to the bowling alley. If the 3-2 vote was not sufficient to authorize operating a bowling alley, then, obviously, Arnie had no actual authority to lease one on behalf of the LLC. The LLC was still limited to operating a restaurant only. 11 If Arnie has no actual authority, it’s hard to see an argument for apparent authority. See RSA § 8. Arnie said he had authority, but a communication by the agent himself cannot create apparent authority. Weber did not communicate with anyone other than Arnie. He read the operating agreement, which could be treated as a communication from the LLC, but nothing in the operating agreement would give Weber the impression that Arnie was authorized to lease a bowling alley. In fact, it would do just the opposite: it indicates that Arnie is only authorized to lease a restaurant. Implied authority is also unlikely to exist, because RULLCA § 301 itself negates any inference that a member has implied authority merely because he’s a member. And nothing in the grant of authority to lease a restaurant implies authority to lease a bowling alley as well. Thus, if Arnie does not have actual authority as a result of the March 1 vote, La Comida is probably not bound on the lease. 12 Question 8 Shareholders of MBCA corporations such as Murk have the right to obtain certain books and records of the company. See MBCA § 16.02. Under MBCA § 16.02(a), any shareholder may obtain the corporate records listed in section 16.01(e) by giving written notice to the corporation. No further showing is required. Unfortunately for Gail, the comment log would not fall within any of the items listed in section 16.01(e): the articles of incorporation; the bylaws; board resolutions relating to classes of shares; and records of shareholder meetings. Therefore, to obtain the comment log, Gail must turn to section 16.02(b). To obtain documents under section 16.02(b), Gail must show that her demand was in good faith and for a proper purpose and, in her request, she must describe her purpose and the records she wishes to inspect. MBCA § 16.02(c). The MBCA does not define “proper purpose,” but courts generally construe the phrase to mean a purpose related to one’s interest as a shareholder. Determining the effect of corporate policies on the company’s profitability and communicating with shareholders about electing different directors seem to be proper purposes. If Gail’s sole aim were to publicize her environmental cause or to change the company’s policies purely for political reasons, her purpose might not be proper, but she has tied her request to the profitability of the company and her interest as a shareholder. Moreover, the documents she wants are directly tied to that purpose. She seems to meet the requirements of section 16.02(c). The problem is that the documents she wants don’t seem to fit into any of the categories of documents that shareholders may inspect under section 16.02(b). These clearly aren’t board or shareholder meeting minutes. MBCA § 16.02(b)(1). And consumer complaints don’t seem to qualify as accounting records, MBCA § 16.02(b)(2); they are not part of the financial statements and they would not be used to prepare the financial statements. An accountant would never need to review these records. And, of course, the log is not a record of shareholders. MBCA § 16.02(b)(3). Therefore, although she has a proper purpose, Gail is not entitled to this particular record under section 16.02. There is another possibility. Section 16.02 doesn’t affect “the power of a court, independently of this Act, to compel the production of corporate records for examination.” MBCA § 16.02(e)(2). Thus, even if Gail is not entitled to these records under section 16.02, the court may still grant her access to these records, if the court feels it is appropriate.