Kang_Yu - Academic Commons

advertisement

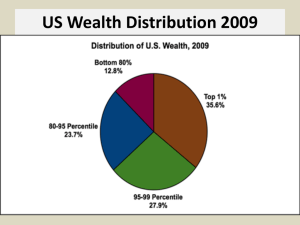

Race & Ethnicity in American Politics Professor Smith Spring 2015 Issue Brief – Final Draft Yujin Kang Socioeconomic Heterogeneity among African-Americans Keywords: Socioeconomic status, minority, African-Americans, class divide, income Description: Does the growing polarization in socioeconomic status make the African-American population more heterogeneous in terms of political alignment and racial attitudes? Does such polarization encourage middle class blacks to align with middle class whites, ultimately diluting the cohesiveness of the African-American community? Key Points: ● The class differences within the African-American community have created a spatial segregation, as the emerging black middle class is moving to the suburbs whereas the underclass remains in the poor metropolitan areas. ● However, there is a persisting gap between the black and white middle class in terms of economic mobility. ● The class differences also contribute to the variation in views on racial inequality, where middle class blacks are less likely than lower class counterparts to consider individual attributes as basis for inequality. ● Although the economic success of middle-class blacks has provided grounds for realignment with the “dominant” group (white middle class), the political party alignment of African-Americans has not substantially changed over time. ● Despite the growing class differences, there is no significant or empirically proven effect on the internal cohesiveness of the African-American community. 1 Issue Brief: Over the recent decades, the variation in socioeconomic status (abbr. SES) among African-Americans has increased, “dividing” the black population along class lines (Hwang et al, p.1). Some scholars contest that, “because of government efforts, such as Affirmative Action programs, black Americans with better qualifications and resources are able to experience unprecedented upward mobility,” suggesting the increasing spatial and socio-economic chasm of African-Americans (Hwang et al, p.1). First question is: does the variation in party identification correspond differences to the of class African- Americans? According to the recent data above, approximately 62% of themselves blacks as identify Democrats, whereas a mere 6% of them categorize themselves as Republicans (Pew Research Center, p.62). According to the table above, despite the growing class differences, an overwhelming majority of blacks still support the Democratic Party. From 1990 to 2007, 76 to 84% of blacks identified themselves as Democrats, whereas 9 to 14% of them aligned with the Republican Party. Such trend seems continuous, substantially unaffected by the growing class gap among blacks. Thus, it is evident 2 that the impact of growing socioeconomic heterogeneity within the black community on party identification variation remains insignificant. Although the variation in SES among blacks does not identification, it affect or alter party discloses difference in attitudes towards racial inequality among blacks. The empirical findings suggest that, “close to two-thirds of the respondents believe that lack of opportunities are responsible for blacks’ poorer education and jobs; yet 36% of them believe that blacks themselves are to blame,” explaining how middle class blacks are less likely to blame the lack of opportunities for receiving poorer education and jobs compared to their counterparts (Hwang et al, p.4). If the class differences among blacks do not affect or alter party preferences, do they have any significant effect on the in-group cohesiveness of the African-American community? Some scholars have speculated that the emergence and growth of “middle class blacks” would essentially divide the black community because the wealthier blacks 3 would socially identify with the dominant middle class whites, as “middle-class blacks [would be] less ethnocentric in their social orientation because of their presumed closeness to whites” (Hwang et al, p.2). However, the Median Wealth graph illustrates how slightly over half of blacks view themselves as a single race and explain why middle class blacks do not entirely identify with the dominant middle class whites. First, there is a significant difference between the “middle class whites” and “middle class blacks,” as Pattillo-McCoy asserts that, “the reality, however, is that even the black and white middle classes remain separate and unequal” (PattilloMcCoy, p.2). The white middle class’ median wealth ranges from $80,000 to $180,000, whereas the black middle class’ median wealth ranges from $20,000 to $40,000. The considerable income gap between the middle class whites and blacks ultimately hinders the latter from socioeconomically identifying with the former. The economic mobility gap between the middle class whites and blacks further discourages the latter group from socially and economically aligning with the former (Isaacs, p.1). Isaacs affirms that, “...almost half (45 percent) of black children whose parents were solidly middle class end up falling to the bottom of the income distribution, compared to only 16 percent of white children,” suggesting the allure of middle-income status among blacks (Isaacs, p.2). Moreover, the segregated housing market further discourages the middle class blacks from aligning with the dominant white middle class. Pattillo-McCoy contends that, “ the black middle class overall remains as segregated from whites as the black poor…[therefore] the search for better neighborhoods has taken place within a segregated housing market. As a result, black middle-class neighborhoods are often located next to predominantly black areas with much higher poverty rates” (Pattillo-McCoy, p.25). Thus, despite the emergence and growth of “black 4 middle class,” the income and economic mobility gap, and the segregated housing market maintain the socio-economic chasm between the white and black middle class. It is apparent that the income gap between lower and middle class blacks has increased the level of heterogeneity among the African-American population; however, its effects on ingroup cohesiveness and political realignment are marginal at best. The empirical findings by Hwang, Fitzpatrick and Helms further suggest that, “the largest difference between middle- and lower-class black Americans is in regard to their political activism…[there is] no significant difference between the two groups in terms of in-group cohesiveness” (Hwang et al, p.5). Hence, it is evident that the socioeconomic variance within the African-American community does not dilute in-group cohesiveness or foster political party realignment. Rather, such differences divide African-Americans’ views on racial inequality. Relevant Websites: Examines ethnic and racial minorities in terms of SES: http://www.apa.org/pi/ses/resources/publications/factsheet-erm.aspx Shows statistical data regarding African-American populations in New York and New Jersey such as income, SES, education, poverty, politics, and so on: http://blackdemographics.com/cities-2/new-york-nj-ny/ Analyzes population dynamics in the United States: http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/00000.html 5 Works Cited: “Blacks See Growing Values Gap Between Poor and Middle Class.” Pew Research Center. (2007): 1-63. Print. Bruenig, Matt. In Reality, Middle-Class Blacks And Middle-Class Whites Have Vastly Different Fortunes. 2013. Chart. DemosWeb. 25 Feb 2015. <http://www.demos.org/blog/8/29/13/reality-middle-class-blacksand-middle-class-whites-have-vastly-different-fortunes>. Hwang, Sean-Shong, Kevin M. Fitzpatrick, and David Helms. “Class Difference in Racial Attitudes: A Divided Black America?.” Sociological Perspectives. 41.2 (1998): 1-6. Print. Isaacs, Julia. “Economic Mobility of Black and White Families.” Brookings Institution. (2007): 1-16. Web. 11 Apr. 2015. <http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/research/files/papers/2007/11/blackwhiteisaacs/11_blackwhite_isaacs.pdf> Pattillo-McCoy, Mary. Black Picket Fences: Privilege and Peril Among the Black Middle Class. 1st ed. University of Chicago Press, 2000. 1-283. Print. ** “Party Identification Trends” table and “Blacks Assess Their Racial Identity” graph have been taken from the Pew Research Center (2007) data, and “Median Income” table has been retrieved from Bruenig. 6