The History of the balcksmith pamphlet

advertisement

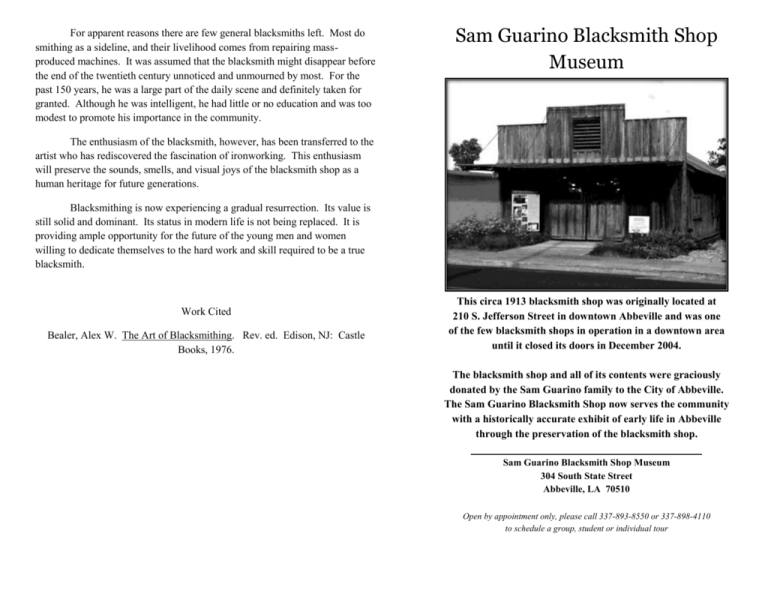

For apparent reasons there are few general blacksmiths left. Most do smithing as a sideline, and their livelihood comes from repairing massproduced machines. It was assumed that the blacksmith might disappear before the end of the twentieth century unnoticed and unmourned by most. For the past 150 years, he was a large part of the daily scene and definitely taken for granted. Although he was intelligent, he had little or no education and was too modest to promote his importance in the community. Sam Guarino Blacksmith Shop Museum The enthusiasm of the blacksmith, however, has been transferred to the artist who has rediscovered the fascination of ironworking. This enthusiasm will preserve the sounds, smells, and visual joys of the blacksmith shop as a human heritage for future generations. Blacksmithing is now experiencing a gradual resurrection. Its value is still solid and dominant. Its status in modern life is not being replaced. It is providing ample opportunity for the future of the young men and women willing to dedicate themselves to the hard work and skill required to be a true blacksmith. Work Cited Bealer, Alex W. The Art of Blacksmithing. Rev. ed. Edison, NJ: Castle Books, 1976. This circa 1913 blacksmith shop was originally located at 210 S. Jefferson Street in downtown Abbeville and was one of the few blacksmith shops in operation in a downtown area until it closed its doors in December 2004. The blacksmith shop and all of its contents were graciously donated by the Sam Guarino family to the City of Abbeville. The Sam Guarino Blacksmith Shop now serves the community with a historically accurate exhibit of early life in Abbeville through the preservation of the blacksmith shop. Sam Guarino Blacksmith Shop Museum 304 South State Street Abbeville, LA 70510 Open by appointment only, please call 337-893-8550 or 337-898-4110 to schedule a group, student or individual tour THE HISTORY OF THE BLACKSMITH by Mary Ann Guarino Blacksmithing is an ancient and honorable occupation. It is one of the larger substantial crafts known to civilized man. As civilizations have diversified, the procedures used have varied little. It was once believed that fire, air, earth, and water were the four basic substances of this world, and only the blacksmith utilized all four. The forge contained the fire, and the bellows restrained or produced the air as needed. Iron and black metal were part of this earth, and water was required to cool the blacksmith’s smoldering iron and to harden his red-hot steel. It is not known when or where man discovered how to make and shape iron. However, making and shaping iron were as essential to progress in ancient times as it is today in the twenty-first century. Only a minority of men possessed the skill to be good blacksmiths regardless of their artistic capability. Traditional smiths had to supply and to repair the tools, weapons, and hardware of their society, and blacksmiths were very essential to transportation. The skills and talents of the man committed to working with iron and steel were definite necessities and guaranteed him a prominent status in his community, especially if the community were to grow and prosper. Until mass production displaced him, the most important task of the traditional blacksmith was supplying the tools of civilization and war. He designed and made hammers, axes, bits, knives, sickles, scythes, auger bits (twist drills), files, chisels, carving tools, spears, swords, arrowheads, and numerous necessities for the farmers and craftsmen in the area. They were all basically dependent on his skills and availability. The smith was also required to weld and fit wagon wheels and hub rings, to shoe horses and oxen, and to fit all the metal parts of wagons, carriages, and sleighs of a horse-drawn society. Blacksmiths needed to maintain high standards of quality in their work. They were not completely dependent on muscles and strength. Intelligence, imagination, visualization, and the ability to improvise and to utilize available materials have always been important and necessary characteristics of a good smith. Until the middle of the nineteenth century, most blacksmiths catered to a general trade. They were asked to accept any job connected with iron. This practice continued until newly developed steam power was gradually used to produce all types of tools through mass production. After this manufacturing evolution occurred, much of the beautiful detail of everyday American life was lost for several generations. The village blacksmith with a tradition of fine workmanship and a good reputation could not compete financially with factories, especially when one man in a factory could make fifty hammers or axes per day instead of two or three using a forge. Soon the blacksmith began to think in commercial terms in order to survive. It became less expensive to buy factory-made hammers and tongs than to make them. Even raw materials were easier to acquire, and the smith was no longer dependent on his scrap pile for stock, so he had more time to work. The blacksmith was the only source of decorative ironwork for expensive homes. Wrought-iron gates, fences, and spikes for the tops of brick walls were all procured from the blacksmith, especially one who specialized in ornamental work. A variety of basic and special kitchen utensils was always required by the general population. Pokers, shovels, ladles, strainers, and spits for roasting meat were definitely in .