Principles of Infectious Diseases

advertisement

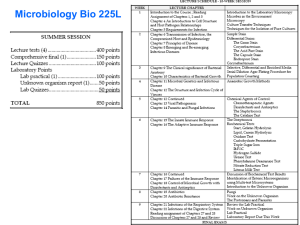

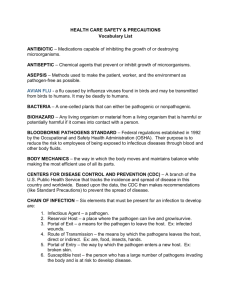

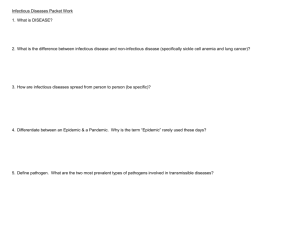

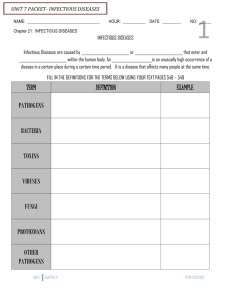

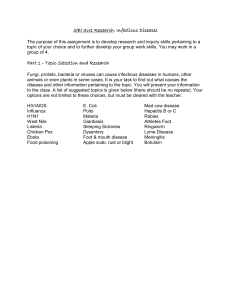

Lesson 10: Principles of Infectious Disease and Disease Prevention Assignment: • Read Chapters 14 and 15 in the textbook. • Read and study the lesson discussion. • Complete the Check Your Understanding activity. Objectives: After you have completed this lesson, you will be able to: • Describe Koch's postulates. • List the important distinguishing features and give examples of major disease agents and discuss the resulting disease. • Relate textbook and discussion material to common presentations. • Name the basic components of disease prevention. • Describe the types of vaccines available and their roles in disease prevention. • Link clinical significance of the academic material studied in this chapter to veterinary practice. Principles of Infectious Diseases Diseases are a major concern for any animal owner. Diseases can be divided into two categories—infectious and noninfectious. There is little to nothing that can be done for animals who are inflicted with noninfectious diseases. Most of these are genetic in nature and can only be managed, not prevented. It is the infectious diseases that owners must be most cognizant of, and that is what we will focus on in this discussion. Definitions In order to have a firm understanding of the principles of infectious disease, it is critical that you understand the basic and fundamental terminology. Dr. John R. Stevenson, Associate Professor in the Department of Microbiology at Miami University, offers clarification of key terms you will encounter as you study animal health. The following information is adapted from his instructional notes on infectious diseases. Most infectious diseases are caused by pathogens, which are microorganisms that are capable of causing a disease. In order for a pathogen to be effective, it must find a host. A host is an organism that provides nutrients and the needed environment for another organism. Remember that there are some beneficial relationships between microorganisms and a host, but in the case of infectious diseases, the relationship is beneficial only to the pathogen. One of the most common pathogens is the parasite, which is an organism that lives at the expense of (and may even harm) its host. A parasite is generally smaller than the host, and it is metabolically dependent upon it. If the parasite and pathogen are able to get through all defenses of the host, they will cause a disease. A disease is defined as an upset in the homeostasis of the host resulting in the generation of observable changes. Observable changes in the animal can appear as signs or symptoms. Signs are objective evidence of damage to the host, such as a fever, rash, or vomiting. A symptom is subjective evidence of damage to the host, such as a headache or anorexia. If the pathogen is able to disturb the homeostasis of the host, it is referred to as an infectious disease. An infectious disease is a disease that causes detrimental changes in the health of the host that occur as a result of damage caused by the parasite. When the animal is diagnosed with an infectious disease, the virulence of the pathogen will be measured. Virulence is a measure of the pathogenicity, which is the ability to cause a disease. The pathogen may be found to be virulent, in which case the microorganism can readily cause disease. Remember: only a small number of the microorganisms are required to initiate and sustain an infection. If the pathogen is attenuated, the microorganisms have a reduced ability to cause disease. Better yet, if the pathogen is deemed avirulent, the microorganism will not cause a disease. An opportunistic pathogen is one that may or may not cause disease. This type of pathogen will generally colonize, but does not infect the host when found within the host. Koch's Postulates To cause a disease, a pathogen must do the following: • Contact the host in some way, which means it must be transmissible. • Colonize the host, meaning it must adhere to and grow or multiply on host surfaces. • Infect the host by proliferating in host cells or tissues. • Evade the host defense system by avoiding contact that will damage the pathogen. • Damage the host tissue by physical (mechanical) or chemical means. Virulence Factors Virulence factors are responsible for the virulence of a microorganism because they influence its ability to cause disease by affecting its invasiveness and/or its toxigenicity. There are several key concepts to become familiar with when discussing the virulence factors of a microorganism. Adhesions enable parasites to attach to host cells or tissues, which is a critical part of the invasion process. Invasins enable parasites to enter and/or move through host cells or tissues, while evasins allow parasites to escape from host defenses. Microorganisms with high virulence factors have toxins, which are poisonous substances that allow parasites to damage host cells. Epidemiology Principles Epidemiology is the study of the occurrence of disease in an animal population, especially the cause (etiology) and the transmission of the disease. Again, students must become familiar with several key terms in order to gain a basic understanding of disease prevention. An epidemic is often a term used in reference to human disease, but it has implications for the animal world as well. An epidemic literally means "upon the people" and commonly refers to an unusually high incidence of a disease in a community or population at one time. In 1952 an outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease in Saskatchewan was brought under control. The disease affects cloven-hoofed animals. All infected and exposed animals were destroyed and buried, and strict quarantine measures were imposed to prevent any escape of the highly contagious virus beyond the buffer zone. The meticulous disinfection of farms, vehicles and all potential carriers was completed. Finally, before the quarantine was lifted, the animals were tested to make sure that all danger of contagion had passed. View this video clip on the precautions taken to contain the epidemic. The following terms relate specifically to epidemics. Prevalence is the proportion or percentage of diseased individuals in a population at one time, while the incidence indicates the number of diseased individuals in a population at one time. A pandemic is a term that literally means "all the people." There is current concern over the potential for the bird flu to become a pandemic. An endemic means "in the people" and is a disease that is constantly present, but usually at a low incidence in a population. Many of you have heard of or used the term outbreak, which is an appearance of several cases of a disease, usually in a short period of time, in an area previously experiencing no cases or only sporadic cases of a disease. Once an illness has reached a certain stage—an epidemic of anthrax in a buffalo herd, for example—there are certain terms that are used to distinguish its effects. Morbidity is the number of animals in a herd that are expected to come down with a disease in an epidemic situation. The mortality rate is the percentage of animals that will die when symptoms begin to appear. Every disease that has been researched and studied has a morbidity and mortality rate. Some diseases, such as rabies, has an extremely low morbidity rate but an extremely high mortality rate. The mortality rate of rabies is 100%. Many diseases, such as anthrax, can stay alive a long time in the environment. A reservoir is a term that is used to describe a site in which infectious agents remain viable (alive) and from which infection of individuals may occur. It is at these reservoirs that a microorganism can become a carrier, which is an infected individual not showing obvious signs or symptoms of clinical disease. Even though there are no obvious signs of the disease, the carrier is still shedding the etiological agent for a long period of time. A vector is a living organism which transmits infectious agents. Ticks, fleas, flies, and mosquitoes are common vectors. A fomite is a non-living object that transmits infectious agents and can include almost any object that is shared among animals. Fomites that are food- or water-based are called vehicles. In some instances, diseases can be transmitted from animals to humans. These are referred to as zoonoses. Plague, Lyme disease, and Rocky Mountain spotted fever are examples of zoonotic diseases. All animal owners should be aware of the concept of zoonoses. Veterinarians are trained in this as they must keep themselves safe from zoonotic diseases. Transmission of Infectious Diseases There are several stages of transmission of pathogens and microorganisms. The first stage of transmission is escape from the old host. Remember that a majority of pathogens have a life cycle that includes being excreted from the animal through feces. This part of the life cycle is crucial for the microorganism's species survival. Then, the microorganism will travel to a new host. This is usually done by the new host animal eating around the fecal material of the old host. This is the main way microorganisms are transmitted from host to host. The final stage of transmission is entry into the new host. There are two modes of transmission for pathogens. They are direct and indirect. Direct transmission includes transmission via close but not intimate contact, such as touching. The second direct transmission is through intimate contact, including sexual contact. Indirect contact is transmission via vectors and vehicles or fomites. Fomites are basically almost anything an infected animal can touch, upon which can be left a residue of contagious pathogen. Types of Epidemics There are two basic types of epidemics—common source and propagated. Common source epidemics include infection or intoxication of many animals from a single contaminated source and are characterized by a rapid onset, a sharp peak, and rapid decline in incidence. A propagated epidemic is one that begins with an introduction of an infected animal into a susceptible population leading to the transfer of the etiological agent to others, who then transfer it to many others. This type of epidemic is characterized by slow onset, a blunted peak, and slow decline of incidence. When new pathogens are introduced into susceptible populations, there is often a rapid onset of epidemics that continue until sensitive individuals in the population are selected against or many individuals in the population develop immunity (herd immunity) and survive the disease. Acquiring Infections in the Vet Office Vet offices are good places to acquire infections and other pathogens due to the presence of many patients with infectious diseases. An infection that is the result of a medical procedure is referred to as an iatrogenic infection. Injections and surgeries are common causes of iatrogenic infections. Transmission of microorganisms can also occur between patients if proper sanitization is not used. Veterinary hospitals should be aware of crowding which leads to crosscontamination of patients by direct and indirect means. Another area of concern in the vet hospital is that of the immunocompromised. Some animals are more susceptible to pathogens because their immune systems are weakened or not fully functioning. Animals can become immunocompromised due to disease, medical treatment, age, and stress. This means that veterinarians must be aware of their patients and take extra care if the animal is immunocompromised. A final area of concern in veterinary hospitals is that of antibiotic-resistant strains of an infection. This leads to problems in the vet clinic if a strain of infection is present that is resistant to antibiotic treatments. Health Measures for the Control of Epidemics Several strategies are employed to break the "chain of transmission." The first strategy is immunization of the species. Humans do this all the time, and the classic example is the flu vaccine. Booster shots are frequently required because the aim of this immunization is not full immunization as the flu virus is continually changing and adapting. In animal health, quarantine is a common practice to prevent the transmission of infectious diseases. This is a simple concept which keeps all infected animals isolated from others to prevent future spread of the pathogen. The minimum time required for a quarantine period is equal to the longest period of communicability of the disease. In other words, animals should be isolated long enough to know that the pathogen has no chance of being transmitted to other animals. The elimination of animal reservoirs is also a common strategy for controlling a pathogen. This includes immunizing animals that act as reservoirs of diseases. At times, eradication of animals that act as reservoirs may also be required. In the case of the bird flu epidemic, millions of birds were destroyed in Asia to prevent further spread of the disease. This is why there are such strict regulations regarding animals and animal products being imported from foreign countries. We do not want to end up with a pathogen that we have no way of controlling. It is important also if you travel to foreign countries to make sure you are properly immunized so that you do not become ill from a foreign pathogen, or become a carrier of any pathogens. Disease Prevention The following information has been adapted from an article originally written by Dr. Ernest Mochankana, titled "Importance of Pet Vaccination." Animals, like people, can be protected from some diseases by vaccination. Although this discussion provides basic information about vaccines for an animal, a veterinarian is always the best source for advice regarding an animal's vaccination needs. What are Vaccines? Vaccines are health products that trigger protective immune responses in animals and prepare them to fight future infections from disease-causing agents. Vaccines can lessen the severity of future diseases, and certain vaccines can prevent infection altogether. Currently, there are a variety of vaccines available for use by veterinarians. Is it Important to Vaccinate? Absolutely. Animals should be vaccinated to protect them from many highly contagious and deadly diseases. Experts agree that widespread use of vaccines within the last century has prevented death and disease in millions of animals. Even though some formerly common diseases have now become uncommon, vaccination is still highly recommended because these serious disease agents continue to be present in the environment. Does the Vaccination Ensure Protection? For most animals, vaccination is effective and will prevent future disease. Occasionally, a vaccinated animal may not develop adequate immunity and, although rare, it is possible for these animals to become ill. It is important to remember that although breakdowns in protection do occur, most successfully vaccinated animals never show signs of disease, making vaccination an important part of the animal's preventative health care. Are There Risks to Vaccinations? Although most animals respond well to vaccines, like any medical procedure, a vaccination carries some risk. The most common adverse responses are mild and short-term, including fever, sluggishness, and reduced appetite. Animals may also experience temporary pain or subtle swelling at the site of the vaccination. Although most adverse responses will resolve within a day or two, excessive pain, swelling, or listlessness should be discussed with a veterinarian. Serious adverse responses occur rarely. A veterinarian should be contacted immediately if an animal has repeated vomiting, diarrhea, whole body itching, difficulty breathing, swelling of the face or legs, or collapses. These signs may indicate an allergic reaction. In very rare instances, death can occur. Visit with a veterinarian about the latest information on vaccine safety, including rare adverse responses that may develop weeks or months after the vaccination. Remember that while vaccination is not without risk, failure to vaccinate leaves your animal vulnerable to fatal illnesses that are preventable. Why Do Young Animals Require a Series of Vaccinations? Very young animals are highly susceptible to infectious diseases. This is especially true as the natural immunity provided in their mother's milk gradually wears off. This concept was discussed in Lesson Eight. To keep gaps in protection as narrow as possible and to provide optimal protection against disease for the first few months of life, a series of vaccinations are scheduled, usually three to four weeks apart. For most young animals, the final vaccination in the series is administered when they are twelve to sixteen weeks old. Which Vaccines Should a Young Animal Receive? A veterinarian should discuss an animal's lifestyle, access to other animals, and travel to other geographical locations, since these factors affect the animal's risk of exposure to disease. Not all animals should be vaccinated with all vaccines just because these vaccines are available. "Core" vaccines are recommended for most animals in a particular area. "Non-core" vaccines are reserved for animals with unique needs. A veterinarian will consider the animal's particulars, the disease at hand, and the application of available vaccinations to customize a vaccine recommendation for the animal. How Often Should an Animal be Vaccinated? A veterinarian should tailor a vaccination schedule to suit an animal's needs. For many years, a set of annual vaccinations was considered normal and necessary for animals. Veterinarians have since learned more about diseases and animals' immune systems, and there is increasing evidence that immunity triggered by some vaccines provide protection beyond one year. The immunity triggered by other vaccines may fail to protect for a full year. More than one successful vaccination schedule is possible. A veterinarian should always be ready to discuss what is best for an animal. A final thought … Many factors are taken into consideration when establishing an animal's vaccination plan. A veterinarian will tailor a program of vaccinations to help the animal maintain a lifetime of infectious disease prevention. Summary Koch's postulates are very important principles in regard to infectious diseases. Knowing and understanding these postulates and the four major disease agents is vital for veterinarians, as this knowledge helps them identify, prevent, and treat infectious diseases. Additionally, tailoring vaccination programs to each specific animal also helps prevent the spread of diseases. Sources Cited: Mochankana, Dr. Ernest. "Importance of Pet Vaccination." Botswana College of Agriculture. 2007. 2 Jan. 2007 <http://www.bca.bw/NewsEvents/Vaccination.htm>. Stevenson, John. "Principles of Infectious Diseases and Epidemiology." Department of Microbiology, Miami University. 19 Aug. 2004. 1 Jan. 2007 <http://www.cas.muohio.edu/~stevenjr/mbi111/disprinepid111.html>.