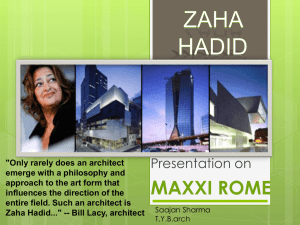

MAXXI Report-Final

advertisement

Jessica Welch MAXXI Museum Case Study Ever since the fifteenth century, art collections have been a favorite recreational site of civilized society. With modern society, the concept of the specialized art museum was introduced. Since its emergence, the architecture and design of such sites have been changing rapidly. The art of current society has induced a grand debate in the architectural design of art museums, focusing on whether such institutions should be works of art in themselves or whether they should display a neutral backdrop so as not to detract from the works they hold. Frank Gehry argued, “The biggest problem is that there is no consensus on what a museum is and what the needs of a museum are. Except that there is a very strong mythology accepted by most architects: that a museum for art has to be differential and neutral in order that it does not compete with the art” (Mack, 23). Zaha Hadid says that as modern art is about the invention and spread of new perspectives on life, art centers should in turn be a forum for the unknown and untested to thrive. Therefore, modern art centers face the challenge of being an anti-institutional institution, of embodying a, “refusal to perpetuate the status quo as a demonstration that things might be otherwise” (Racana, 24). This very thought process is exemplified in Hadid’s recent work, the MAXXI Museum in Rome. Hadid Architects claim that the building is a catalyst for the implementation and exchange of ideas, a series of galleries where you can experiment with the very idea of galleries, light and movement. Thus, the museum is a vehicle for experimentation in exhibition, collective communication and social gathering. MAXXI stands for the “Museo Nazionale della Arti del XXI Secolo” or the “National Museum of XXI Century Arts”. It is Italy’s first nationally funded museum dedicated to contemporary works of art and architecture. Within the campus are two institutions, MAXXI Arte and MAXXI Architecture that focus on promoting these two fields through collection, conservation, study and exhibition of works. The architecture of the building can be characterized by two main elements; the concrete walls that allow the flowing, intersecting volumes and the transparent roof that controls entrance of natural light. The roof uses louvers that allow the control of natural sunlight into the space. This use of light is important in such a space as light can have a strong impact on both the preservation and viewing of pieces of art and architecture. The skylight is broken up by long fin projections that protect the work from direct sunlight. This system creates lively, warm light and allows visitors to occasionally see the outside. The light, modulated by long fins, also emphasizes the linearity of the space and highlights the feeling of forward momentum and the overlapping of galleries. There is also a strong formal structure of striation involving parallel lines that constitute the walls, beams, staircases and lighting strips of the space. The space seems to flow as its concrete construction presents visitors with a seemingly uninterrupted, moving space. The building contains exhibition space comprised of five suites that are independent, yet, connected to promote fluidity. Each suite has a different internal geometry and thus a unique microclimate, allowing for a myriad of possibilities for the instillation of artwork. Upon entering the atrium, the main elements of the building are clear: curved concrete walls, suspended black staircases and an open ceiling to catch natural light. These elements embody Hadid’s intention of, “a new fluid kind of spatiality of multiple perspective points and fragmented geometry, designed to embody the chaotic fluidity of modern life” (http://www.fondazionemaxxi.it/?lang=en). The building layout is comprised of a major stream of curves that form the galleries, as well as a secondary stream of curves that create the bridges to connect adjacent buildings. The use of poured concrete allowed for rippling walls that can be used as display spaces both inside and out. The plan is also open with no secondary interior walls but rather moveable screens for the display of artworks making the institution infinitely flexible. The building is meant to embody a new architectural style that Hadid Architects call “parametricism”. This style aims to organize and express the complexity of social institutions and modern life by focusing on external continuity into the urban context of a building and the themes of differentiation and correlation. A key factor in the design of the MAXXI museum is the unique design process of Zaha Hadid. This famous architect does not start her design process with a solid form or regular geometry, but rather with what appear to be scribbles. She creates paintings and open sketches that embed in the work a study of movement and a unique quality of openness and connection to the environment. It is this very process that creates the fluid character which Hadid finds incredibly important in architecture. “In all her work, Hadid is concerned with movement and speed-both the way people will move through the buildings and the way a sight line travels through light and shadow. Her exteriors seem to be shaped by the movement inside and around them, rather than by some predetermined notion of external form” (Seabrook). When asked about her design concept, Zaha Hadid replied that the MAXXI museum should not be seen as one building, but several. “We wanted to move away from the idea of ‘the museum as an object’ and towards the idea of a ‘field of buildings’” (Racana, 15). The main force of the project is the walls that constantly converge and diverge to create indoor and outdoor spaces. The result is a site that is not just a museum, but also a cultural center. It is a building that is not an object, but rather, “…a field within a field, and the two fields [are] sucked into the building” (Racand, 8). In plan view, it is clear that the project is a force field of lines, a landscape field project in which individual pieces cannot be separated. Within such a field, single elements are never what are important, but rather the qualities that are created from the interaction of all the elements. Hadid argues that the "energy" and "field" and "ground conditions" of her spaces are a reflection of the dynamism of a city rather than the static building within a city. The resulting building composition is what Hadid likes to call an “urban field” for exhibits and visitors. “It's infused with a formal dynamism in the fluid configuration of its connecting, intertwined spaces, served up in lashings, dollops and clusters, rather than sequestrated… [resulting in] a three-dimensional game of snakes and ladders” (Seabrook). This innovative design brings a new element and meanings to the works of art that it holds. It is a building based on directional drift and density rather than key areas. With the abandonment of the object we find ourselves faced with a field of multiple associations that anticipates and allows for change. Art today is an area that pushes us to experiment and view the world in new and innovative ways. This goal is underlined and emphasized by Hadid’s design of a dynamic, interactive, flexible space that allows for countless new connections, communications and innovations. The field quality of the MAXXI Museum is very innovative in that it allows the building to interact with its environment. It is located on a former military compound of barracks in the Flaminio section of Rome. This is an area just outside the historical section of the city where Rome has created an open zone for modernist architecture. The site was a challenge as the plot of land is in an awkward L-shape and some of the barracks had to be kept in the new structure. Thus the individual structures had to be a mixture of old with new just as the building would be an integration of the new into an old city. “In Rome, history flows through every urban artery and for architects, the Eternal City presents history as inspiration, obstacle, and challenge. With the…MAXXI… Zaha Hadid treats it as a river -- a fluid construct comprising a series of streams -- converging, overlapping, then changing course. In the process, she taps into powerful flows of the Roman past” (Pearson). She does this through various elements such as her use of light to create an almost buoyant structure (a technique Bernini employed) as well as the movement, asymmetry and convex and concave curves found in Baroque architecture. Another aspect of similarity between MAXXI and Roman tradition is the use of exaggerated perspective to create a highly optical space. “The building is deeply Roman in concept and finesse while being postclassical.” (Racand, 14). The structure incorporates existing military buildings while creating a plaza along the site that makes a pedestrian path through the city block. The building twists to align with the existing streetcar line and its full size cannot be seen until one walks past the existing military structures into the plaza. In this way, it is not a startling form on the street front. It seems to integrate perfectly into the site due to its allusion to the nearby Tiber River and its connection of different city grids. Every line within the structure is either parallel or perpendicular to the existing city streets. Therefore, every line agrees geometrically with the buildings around the site. “The geometry belongs to its context” (Racand, 22). In the end, Hadid’s museum is a building that integrates itself into the urban layout of its location, binding everything together, while at the same time critiquing the lack of complexity in its neighboring buildings. The design was a reinterpretation of its urban context that resulted in new, surprising complexity while at the same time creating cohesion and flow in the space through the use of graceful, harmonious lines. The building shows an appreciation for the larger system that is the city block and the greater history of Rome and is an exemplary case study for how architects can approach design within an already existing, large, complex, system. Bibliography Betsky, Aaron, and Zaha Hadid. Zaha Hadid : Complete Works. Rev. and expanded ed. New York, NY: Rizzoli International Publications, 2009. Hadid, Zaha, Alvin Boyarsky, and Yukio Futagawa. Zaha M. Hadid. Tokyo: A.D.A. Edita, 1986. Heathcote, Edwin. "Back to the Future: Rome's Newest Art Museum Will Help Propel the Ancient City into the 21st Century." Financial Times [London] 02 Jan. 2010, Life and Arts sec.: 7. Web. Henderson, Justin. Museum Architecture. Gloucester, MA.: Rockport Publishers , 1998. Horowitz, Jason. "An Ancient City Becomes More Receptive to Modern Architecture." The New York Times 13 Apr. 2005, Arts/Cultural Desk sec.: 3. Web. Iliescu, Sanda. The Hand and the Soul : Aesthetics and Ethics In Architecture and Art. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2009. Mack, Gerhard, and Harald Szeemann. Art Museums Into the 21st Century. Basel: Birkhäuser, 1999. "MAXXI." Architects Journal (2010). Web. MAXXI Museo Nazionale Delle Arti Del XXI Secolo. Web. 02 Nov. 2011. <http://www.fondazionemaxxi.it/?lang=en>. Murphy, Mimi. "21st Century Rome." Town & Country 164.5360 (2010): 84. Web. Ouroussoff, Nicolai. "Modern Lined for the Eternal City." New York Times 12 Nov. 2009, Architecture Review sec.: 1. Web. Pearson, Clifford A. "MAXXI." Architectural Record 198.10 (2010): 82-91. Web. Powell, Kenneth. "Radical Possibilities." Architects Journal 210.1 (1999): 22. Web. Racana, Gianluca, and Manon Janssens. Maxxi : Zaha Hadid Architects. New York: Skira Rizzoli, 2010. Seabrook, John. "The Abstractionist: Zaha Hadid's Unfettered Invention." The New Yorker 21 Dec. 2009: 113. Web. Zaha Hadid Architects. Web. 02 Nov. 2011. <http://www.zaha-hadid.com/>. Zargani, Luisa. "To the Maxx." WWD 199.115 (2010): 16. Web.