- New Jersey State Association of Occupational Health

advertisement

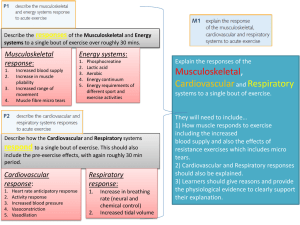

Guideline Title- Evidence-based Safety Guideline to Reduce the Risk of Musculoskeletal Injuries for Older Adults in the Workplace Target Population Intended Users Workers 55 years of age and older Manufacturing & Nonmanufacturing Settings Occupational Health Nurses Occupational Health Nurse Practitioners Advanced Practice Nurses in Adult Nursing Guideline Status This is the first release of the guideline. Guideline Objectives 1. To increase OHN knowledge of factors that increase risk of musculoskeletal injury to older adults 2. To perform a comprehensive assessment of physiological age-related changes 3. To increase knowledge in performing an ergonomic assessment 4. To implement prevention strategies to reduce risk of injury Major Outcomes To blend workplace health and safety with our National Health Care Reform initiatives to improve the overall health and safety of Americans with a focus on the aging population. To increase OHN knowledge to help reduce the risk of musculoskeletal injury for older adults in the workplace The intent of this evidence-based safety guideline is to increase occupational health nurses knowledge to help reduce the risk of musculoskeletal injury in older adult workers through primary and secondary prevention and education. It is wise for the OHN to take a holistic approach to deliver care to older adult employees to improve overall health and consequently reduce the risk of musculoskeletal injury. Early detection of symptoms is paramount to decrease the risk of injury, to decrease injury associated costs and to prevent chronicity. Knowing how to distinguish between what is occupational and what is non-occupational is a critical skill for OHNs to have. The worker health benefit is reduction of musculoskeletal injury risk factors and improved health. The organizational benefit is a sustainable aging workforce. There are no side effects or risks. Methodology Methods used to Collect/Select the Evidence © 2014 Nancy Delloiacono, MSN, RN, APN-BC 1 Hand-searches of Published Literature (Primary Sources) Hand-searches of Published Literature (Secondary Sources) Electronic databases search from 2005-2013-MEDLINE, CINAHL, Business Source Primer Search Terms- Medline-musculoskeletal disorders, older adult workers yielded 987 results with no filters, 2005-2013 with full texts yielded 487 results; CINAHL-aging workforce, chronic illness with no filters, 1994-2013 yielded 49 results, nursing yielded 49 results, filtered with full text -24 results; Business Source Primer-aging workforce, safety filtered with full text, 20072012 yielded 133 results Description of Methods Used to Collect/Select the Evidence AGREE 2 Evaluation of the American College of Occupational and Environmental MedicineMedical Specialty Society Low back disorders: Evaluation and management of common health problems and functional recovery in workers; Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing-academic institution for age-related changes in health. In: Evidence-based geriatric nursing protocols for best practice; and American Occupational Therapy Association Occupational therapy practice guidelines for individuals with work-related injuries and illnesses. Methods Used to Assess the Quality and Strength of the Evidence CEBM Levels of Evidence See Appendix A Evidence to Support this Guideline See Appendix B References to Support this Guideline See Appendix C Description of Method of Guideline Validation Internal Review Doctoral Committee Members- Dr. Judith Barberio, PhD, RN, APN-c Committee Chair; Clinical Assistant Professor, Rutgers, the State University College of Nursing; Dr. Edna Cadmus, PhD, RN, NEA-BC, Clinical Professor & Specialty Director, Nursing Leadership Program, Rutgers, The State University College of Nursing and Dr. Dean Wantland, PhD, RN, Assistant Professor, Rutgers, The State University College of Nursing. External Review Dr. Jacqueline Agnew, PhD, MPH, RN, John Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, John Hopkins Center for Injury Research and Policy reviewer of draft 1 Evidence-based Safety Guideline to Reduce the Risk of Musculoskeletal Injuries for Older adults in the Workplace 2 Dr. Joy Wachs, PhD., RN, Professor, East Tennessee State University and Editor of Workplace, Health and Safety reviewer of national guidelines utilizing the AGREE 2 evaluation Dr. Barbara Burgel, PhD., RN, Clinical Professor in Community Health track at University of California San Francisco reviewer of national guidelines utilizing the AGREE 2 evaluation Assessment Points of Interest Client Musculoskeletal History Musculoskeletal disorders-“Injuries or dysfunctions affecting muscles, bones, nerves, tendons, ligaments, joints, cartilages and spinal discs.” Includes tears, sprains, strains, carpal tunnel syndrome, pain, soreness, hernias and connective injuries of the structures mentioned (daCosta & Vieira, 2009). Overexertion injury-sprains, strains (scope: low back, shoulder, neck, knee, hand, wrist, ankle & foot) Falls (single, multiple) How long ago did the fall occur? Fractures- resulting from overuse or trauma, underlying osteopenia Low bone mass Osteoporosis-Most common over age 50 Low Vitamin D level Weight changes ( weight loss may or may not indicate a red flag) Dehydration Pain & location (especially widespread pain), pain scale, aching, cramping, stiffness, tenderness, edema Itchy, dry, sore eyes, double or blurry vision Sleep alterations Musculoskeletal Functional Assessment-activity level, exercise pattern, flexibility, gait, balance, strength, energy level, endurance Fall risk assessment, if indicated. For information on The Hendrich 11 Fall Risk Model go to: http://consultgerirn.org/uploads/File/trythis/try_this_8.pdf Occupational psychological factors- job satisfaction, work relations, monotonous tasks, perceived work ability, stress and demands Medical History Arthritis-osteo, rheumatoid, psoriatic. Knee is the joint most affected by arthritis. Cardiovascular-There is a progressive decline in the functional capacity in the older adult. Heart rate and perceived work stress is lower for older adults with higher levels of aerobic fitness. Hypertension or Hypotension postural changes Respiratory- clinical measures and risk factors such as family history, genetics, occupation & smoking, asthma, chronic bronchitis, emphysema, COPD Neurologic- headaches, stroke, numbness, tingling, burning sensation in hand, decreased sensation Diabetes, micro-vascular changes, A1c results 3 Seasonal allergies Chronic fatigue-Older adults need more recovery time for muscles used on the job. If not enough rest and recovery time, it leads to fatigue and injury. Limitations Visual, night blindness Auditory Mobility Co-ordination Dexterity Psychosocial History Self- imagined age Life and career stage Cigarettes, cigars, alcohol, drugs Depression, anxiety, stress, concentration, mental resilience, sleep patterns Method of relaxation Socialization Supervisor/employee working relationship Job satisfaction- Medication Safety Risk Prescription and OTC- Pay particular attention to antihistamines, pain relievers, muscle relaxers, anti-anxiety & antidepressants Job Impact Job history- Date of hire, previous jobs and type of work, part-time/full-time, length of time functioning in an ergonomically demanding environment High job demand (frequent interruptions, deadlines, social support, social support), risk of injury increases Low job control (no job variability, limited choice of how work should be accomplished), risk of injury increases Physical work demands-(There is strong epidemiological evidence that physical demands(lifting, bending, manual materials handling and twisting and whole body vibration can be associated with increased reports of back symptoms, aggravation of symptoms and injuries”(Waddell &Burtob, 2001). Strong evidence exists for remote & mobile workers indicating the low back pain prevalence rate is 25% for men & 35% for women (Crawford et al, 2011). Extended work day Posture-back & wrist support, height of chair & monitor, placement of document holder Amount of repetitive movement such as typing, assembly line work Amount of overhead reaching Amount of daily time spent at computer Shift work(rotational, a series of day shifts alternating with a series of night shifts) 4 Stress (home\work balance, social support, work breaks, amount of daily exercise, # of hours worked per day, frequency of health provider visits) Supervisor/employee working relationship Engagement in work In addition to questioning worker, evaluate the above ergonomic factors by performing an ergonomic assessment. Physical exam-Utilize an age sensitive approach for pre-employment, general physicals & focused exams Observation of any overall pattern of deformity at rest Observe joints that do not work properly while in use BP (lying, sitting and standing) Extra ocular movement exam (EOM)- assess for ability of the eyes to follow visual targets Snellen Alphabet chart, Rosenbaum or Jaeger, onsite advanced visual testing (dynamic visual acuity (DVA) deterioration begins at approximately age 45) Fundoscopic exam- assess the macula for reading and detailed task work, check for increased sensitivity, glare. Perform color discrimination test. Otoscopic exam-Check for eardrum thickening which can affect sound transmission Check for decreased number of hair cells in inner ear. These changes affect balance. Whisper test. If indicated, do onsite audiometric testing. Thyroid exam- 5% of adults over age 60 have Hypothyroidism. Fine motor function by performing finger to finger touches, tremors Neurologic sensitivity with sharp and dull sensory testing (cotton ball, split tongue blade), monofilament for protective sense( if unable to feel at point where it bends, lost sense & increased risk for injury from trips, slips, falls from same level and falls from heights. Touch changes can lead to peripheral neuropathy which increases risk of falls. Check for shortening of the trunk, kyphosis and diminishing height Check mobility, gait, gait speed. Do the “Tug Test” to check for decreased flexibility caused by decreased synovial fluid. Inspect, palpate and determine ROM & muscle strength for hands, wrists, elbows, shoulder, cervical spine, thoracic & lumbar spine, hips, legs, knees feet & ankles.(reduced grip strength in hands), crepitus, deformity, warmth. Hands, knees, wrists, hips and shoulders more prone to developing arthritis. Phalens Test, if indicated to check for carpal tunnel syndrome. Joint stiffness and swelling Ability to make a full fist and to flatten hand onto a flat surface Ergonomic Assessment Work space design- evaluate the work space and observe the worker performing his/her job 5 Chair seat contact stress ( Internal-blood vessel or nerve stretched around tendon; External-Irritated or constricted blood vessels) Task organization Type of chair (feet need to be flat on floor, backrest support for lower lumbar area, thighs parallel to floor making an 90 degree angle with lower leg, seat pan length appropriate for worker), posture, support Evaluation of upper extremity risk: poorly designed work stations (sitting & standing), sitting position without proper back support, prolonged same position postures Evaluation of lower extremity risk: height of chair, footrest, boxes or files under desk Average daily PC usage (important for evaluating for neck strain) Monitor-distance ( monitor top should be slightly below eye level when worker is seated) position, glare, use of eyeglasses for distance and near, contacts, bifocals Keyboard or keypad(forearms need to be parallel to floor) hand & wrist position, mouse location & height should be same as keyboard Document holder-position Average daily phone usage, if uses a head set (important for evaluating for neck strain) Breaks, mini-breaks, stretching (gives ample time for muscles to recover) High Risk Areas of the Body Low Back Assessment Identify risk factors: bending, twisting, prolonged sitting, pulling, pushing, reaching & climbing. Additional risk factors for work-related musculoskeletal disorders-awkward and or sustained postures, repetitive motion, prolonged sitting and standing, heavy physical tasks, excessive force, elevated BMI & smoking (daCosta & Vieira, 2010). Age related degeneration of tissue occurs, injury and pain are commonly seen in the older adult. Repetitive task increase stiffness and pain Tears, sprains & strains resulting from overexertion on or off job Psychosocial risk factors-low level of job control, negative affectivity, unsatisfied with work Individual risk factors-female gender, co-morbidity, elevated BMI & sedentary lifestyle. Prevention Exercise programs are an important component in helping to reduce injury. Exercise needs to be taught correctly and performed with proper technique. Institute back prevention programs NIOSH(1997) defines a Recommended Weight Limit (RWL) as the weight of the load that nearly all healthy workers can lift over a substantial period of time (ex. 8 hours) without an increased risk of developing back pain. The maximum weight to be lifted with 6 2 hands under ideal conditions is 51 pounds. The RWL is based on 6 variables that reduce the weight to be lifted to less than 51 pounds. See link for variables & additional information http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2007-131/pdfs/2007-131.pdf Do not sit all day (low physical workload) Sitting for long periods of time places the employee at risk for developing back pain. Sitting slows metabolic function which causes weight gain (burns 40 calories an hour as compared to 180 calories an hour when cooking) Encourage 5 minute breaks every hour (helps to avoid fatigue). Encourage stretching during breaks. Do not stand all day (high workload on the body) Recommend alternating positions between sitting and standing. Work load parameters-Lift less than 35 pounds & not more than the horizontal distance of 20 inches from the ankle Incidence of hernias, sprains & strains are not necessarily seen anymore with lifting heavy amounts of weight. Maybe related to being out of shape. Encourage movement of the body ( increases circulation, flexibility & concentration) Walk regularly to a common area printer, to meetings and to lunch. Encourage use of stairs. Discuss with management the consideration of standing desks Recommend an ergonomic chair. If worker has an adjustable seat, reminders of the health benefits are important. Encourage open discussion with workers, so a plan to help can be devised together. Shoulder Assessment Risk factors are heavy lifting & psychosocial factors (daCosta & Vieira, 2010). Insufficient strength Glenohumeral joint(most unstable joint) to perform manual tasks in the workplace Evaluate for subacromial impingement syndrome, rotator cuff and scapular dyskinesia Visually inspect and palpate for tenderness on posterior aspect of scapula Range of motion (ROM) to note quality of movement (active & passive) Perform upper extremity strength testing Perform empty can test to assess for muscle weakness Evaluate posture Muscle assistance testing (active resistance testing) Prevention To help reduce risk of shoulder injury the worker should: have arm free to externally rotate, low frequency of arm elevation & vertical plane should be the primary applied force area 7 Avoid work tasks that require more than 60 degrees of arm elevation (National Institute for (Occupational Health & Safety, n.d.) Neck Assessment Risk factors are prolonged work time at the computer without a break Assess ROM, strength, pain, tension, tenderness, posture & work position Pain scale Prevention Avoid prolonged periods of working at a computer without a break. Avoid overreaching across desk or assembly line When doing heavy physical work, use proper body mechanics Lift appropriate weight limits and use assistive devices when needed. Assessment Risk factors repetition, lifting, award posture & co-morbidity Assess ROM, pain, tenderness Pain scale Prevention Encourage weight reduction if needed Knee Hand, Wrist, Elbow & Forearm, Ankle & Feet Assessment Risk factors for wrist and hand are prolonged computer work, repetitive work, awkward static postures, older age, female, & high distress levels (da Costa & Vieira, 2010). Risk factors for elbow and arm are older age, repetitive tasks, Co-morbidity and awkward postures (daCosta & Vieira, 2010). Assess for ROM, swelling, pain, numbness, tingling, mobility & repetitive movement. Prevention Use of wrist rests Gentle exercises at desk There is a lack of longitudinal studies investigating ankle and feet (daCosta & Vieira, 2010). Eye Assessment Visual correction for near and far vision, bifocals, trifocals 8 Distance working from monitor Posture (eyes usually dominate even if it means being uncomfortable at the desk) Prevention Regular eye exam, adequate visual correction Encourage regular use of corrective lenses Encourage task lighting to reduce glare Laptop users without docking station, suggest a stack of books ( eyes at same level) Adequate breaks These suggestions help prevent eyestrain. Age-related Musculoskeletal Education Age related functional declines and concurrent risk of work related injury can be prevented with the lifestyle addition of regular exercise (Kenny et al, 2008). Between the ages of 40-60, there is about a 20% age-related decline in the functional capacity to accomplish work for the older adult. Physical fitness effects how much decline. Mobility loss, lack of good balance & degeneration of joints increase risk for injury. Health problems that reduce physical activity accelerate the musculoskeletal changes (Seidel, 2010). Loss of bone density has a pronounced effect on the long bones and vertebrae Alteration of muscle mass due to increased quantities of collagen going into the tissues leads to fibrosis of collective tissue (Seidel, 2010). Regular physical exercise training, improves the older workers maximal capacity needed to perform a job and in turn reduces the risk of injury (Kenny et al, 2008). Decline in flexibility & endurance Gait speed can be affected by potential energy and available energy which declines as individual’s age. This finding implies that reserve capacity and the amount of energy available for use regarding all physical activity decreases with age. Gait speed can be affected in individuals with increased fat mass levels- have lower reserve capacity and lower levels of all around energy available for use in physical activity. With the aging process, individuals generally experience some increase with resting blood pressure. Impaired myocardial contractility can result in a lower ceiling of blood pressure for older adults than for younger adults. Older adults also have impairment in reflex adjustments of pressure when they suddenly change posture. “This reflects a low level of cardiovascular fitness, impairment of the cardiovascular reflexes and often creates pathological changes such as varicose veins”. Older adults are at risk to suffer loss of consciousness from postural hypotension episodes (Perry, 1010). Typing and reading, although sedentary tasks require repetitive movement which can cause injury. This risk of injury rises with advancing age (Kenny et al, 2008). 9 Falls Education Medical risk factors associated with falls: Impaired musculoskeletal function Arthritis, hip weakness & imbalance Visual & hearing loss Medication adverse effects Medical condition examples-bone cancer, multiple sclerosis, stroke, Parkinson’s disease cardiac arrhythmias and alterations in blood pressure Personal risk factors Due to normal age-related changes in vision, strength, balance, and the ability to quickly respond to our environment, the risk of falling increases. Decreased activity and exercise compromises coordination, balance, energy level, bone and muscle strength, flexibility & strength (ACOSM, 2011; ACOEM, 2012). As individual’s age, muscle strength and endurance significantly impact the ability to lift heavy objects, participate in repetitive movement and affect the ability to sit or stand for long periods of time (Kenny et al, 2008). Maintaining this strength reduces the risk of injury for older adults. With the aging process, a main contributing factor to decreased strength is loss of skeletal muscle mass (sarcopenia). Smoking decreases bone strength, increases risk for COPD (chronic bronchitis), impairs wound healing & circulation (ACOEM, 2012). Lack of rest and sleep Increasing age factor and highest past body weight- a risk factor for osteoarthritis of the knee (Blagojevicet al, 2010). Risk factors for knee osteoarthritis in older adults-female gender, intensive physical activity, increased BMI, increased bone mineral density ( BMD), Heberden’s nodes, hand OA and occupational activities such as squatting & kneeling (Blagojevic et al, 2010). Job Impact Education Lumber support & steering wheel adjustment will help decrease musculoskeletal symptoms for driving workers. Isolation, lack of social contact & a decreased amount of clients seen per month is a risk factor for traveling sales employees. (Crawford et al, 2011). Moderate evidence exists as to # of hours driving without a break causing fixed postures which increase the risk of neck, upper limb and lower back pain. Crawford et al, 2011). Higher mileage is associated with musculoskeletal symptoms. Moderate evidence for mobile workers to be able to balance work & life. Psychosocial factors are associated with musculoskeletal complaints Job Stress Mistakes & injury can result if the position demands exceed the worker’s capabilities(causes physiological & psychological stress) 10 Repeated exposure to high levels of physiological stress over an extended time period can lead to chronic musculoskeletal injuries as well as disorders (Kenny et al, 2008). OHNs need to assist management in adapting job responsibilities to accommodate the age-related changes that occur with the older worker. This will aid to increase the safety of all employees in the workforce. Medical Risk Factor Education Physiological fatigue results when an older worker’s muscles become overstressed. Along with decreased physiological age-related changes, more often, time is needed to recover physiologically.. Performing a job in extreme hot and cold temperatures presents more difficulties for the older adult than a younger adult. For employees coping with pain at work, encourage them to remain active, avoid provocative movement, educate on use of pain medication( de Vries et al, 2011). Personal Risk Factor Education Primary Prevention Getting Back to Basics-regular exercise, proper nutrition, stress reduction, smoking cessation, adequate sleep and rest limits the effects of aging & decreases risk of chronic disease which in turn reduces risk of musculoskeletal injury Cardiovascular disease places an individual at risk for not healing well with musculoskeletal injuries. Encourage regular exercise and offer exercise programs (strengthening, stretching, balance, flexibility, endurance & possibly resistive) Consult with primary care provider before participating in an exercise program. Always include a 5-10 minute warm up and cool down. Increase muscle strength to assist with decreasing cardiovascular stress during lifting and carrying. Increase endurance for human performance. Increase muscle power to climb stairs, lift, improve stability and prevent falls. Properly conducted resistive training improves these areas, but only engage in these activities with primary care provider approval. Basic Muscular Fitness-Repetitions-10-15 (one set); How often-two to three days a week; eight to ten types of exercises; appropriate weights (ACSM, 2011). Encourage activities that increase energy and help with weight reduction or weight maintenance to help increase gait speed. Start counseling in middle life before gait speed declines naturally. Psychological fatigue can occur when an older worker’s job requires high accuracy work demands, high volume of work, deadlines, frequent distractions and even noise. Secondary Prevention Screen for Prehypertension- blood pressure readings that are higher than normal but have not progressed to the high blood pressure range. Screen for Pre-diabetes- impaired fasting glucose (IFG), impaired glucose tolerance,(IGT) or may have both impairments. 11 Hypoglycemia increases the risk of injury Screen lipids, Vitamin D level Bone density testing Screen for BMI changes (BMI) equal to or more than 25 indicates overweight,( BMI) 30 or greater indicates obesity Screen for COPD- spirometry Vision and hearing screening Hypertension Education Exercise lowers blood pressure Nutritional counseling Diabetes Education For every 1% drop in Hg A1c, the risk of micro-vascular complications increases to 40% Hypoglycemia increases the risk of injury BMI Changes, Obesity Education Losing 5-7% of body weight reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease, stroke, diabetes and some cancers. Walking 30 minutes/day five days a week lowers risk of osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and diabetes Consider pedometer incentive programs. COPD Education Educate that COPD is preventable and treatable Advocate for State COPD Action Plan, smoke free policies, good worker respiratory protection, improved air quality, asthma education Improve exercise capacity Smoking cessation programs Instruct on reducing exposure of fumes and dust at work & home Proper respiratory personal protective measures to reduce exposure General Summary of Recommendations The following is a general summary of recommendations: 1. Early detection of musculoskeletal symptoms is critical to decrease the risk of injury and to prevent chronicity and disability. 2. When taking a musculoskeletal history, key into complaints that may lead to overexertion injury and falls. 3. If indicated, perform a fall risk assessment. Suggested tool- The Hendrich 11 Fall Risk Model 4. When taking a medical history, the onset of chronic disease is important in identifying level of injury risk. Health problems that reduce physical activity accelerate musculoskeletal changes. 12 5. When taking a psycho-social history, factors such as self -imagined age, work\home balance, social support, work breaks, job satisfaction, supervisor /employee working relationship, socialization, relaxation methods and sleep patterns can significantly increase risk of injury. 6. Evaluate for medication adverse reactions which may be increased due to age-related changes and cause increased risk of injury on the job. 7. When taking a job history pay particular attention to length of time functioning in an ergonomically demanding environment. 8. Utilize an age sensitive approach when performing a pre placement physical examination, complete physical or a focused exam on the older adult. 9. When performing a musculoskeletal physical exam pay particular attention to the following: high risk areas of the body (eye, low back, shoulder, neck, hand, wrist, ankle and foot). 10. Perform an ergonomic assessment, evaluate the work space and observe the worker actually doing his/her job to determine the severity of ergonomic interplay on worker symptoms. Encourage open discussions with worker so a plan can be devised together. 11. Refer early to physical therapy to prevent or reduce loss work time and disability. 12. Educate on low back risk factors: bending, twisting, pulling, pushing, reaching, climbing and prolonged sitting. 13. Recommend alternating positions between sitting and standing while working. 14. When assessing the shoulder, evaluate the glenohumeral joint. This is the most unstable joint to perform manual tasks in the workplace. 15. Older adults are at risk for postural changes in blood pressure and are at risk to suffer loss of consciousness from postural hypotension episodes. Educate to change positions slowly. 16. Encourage walking. Decreased activity and exercise will negatively affect coordination, balance, energy level, flexibility and strength which are already decreased in the older adult. 17. Cardiovascular disease places an individual at risk for not healing well with musculoskeletal injuries. Therefore, it is important to educate worker on “The Sitting Disease”. 18. Instruct that lifting 35 pounds or more and lifting more than the horizontal distance of 20 inches from the person’s ankle, increases risk of injury. 19. In jobs that require repetitive movement, encourage adequate time for muscles and tendons to recover by taking adequate rest breaks. 13 Synthesis of Evidence and Levels of Evidence Cited Author/Year Title Study Topic\ Problem Intervention Outcome Results Comments Level of Evidence Blagojevic, M., Jinks, C., Jeffery, A. & Jordan, K.P. (2010) No comprehensiv e SR’s of knee osteoarthritis SR & MA review of studies published from1960Jan. of 2008 Identified factors can help to prevent knee OA Out of 2,233 studies, 85 included in the review. Primary risk factors identified for knee OA -prior knee trauma, Heberden’s nodes\ hand OA, obesity, physical occupational activity(squatti ng ,kneeling)inten sive physical therapy, older age & female gender More longitudinal studies need to be conducted Some publication bias regarding gender, Level 1A Musculosk eletal symptoms can improve with proper ergonomic interventio ns 11 studies out of 280 were utilized & findings show an association between musculoskelet al symptoms, work factors & lifestyle factors Further research is needed to determine if access for mobile workers to OH is an issue Lack of social contact Strong evidence indicates-neck, Risk factors for onset of osteoarthriti s of the knee in older adults: a systematic review and metaanalysis Crawford, J.O., MacCalman, L. & Jackson, C.A. (2011). The health and wellbeing of remote and mobile workers Risk factors, aged 50 & older have increased prevalence of knee OA Potential health & psychosocial effects exist for the remote & mobile worker SR to identify the health effects (musculoskel etal) & psychological effects which influence the state of health of the remote & mobile worker 14 SR & MA Cohort & Case Control studies utilized Metaanalysis limited by small # of risk factor studies Cohort & case-control studies showed consistent findings Case control larger effect size Risk factor for low back pain identifiedcarrying Level 1 A SR RCTs, quasiexperiment al, case reports & observatio nal increases risk of social isolation, social support & mental well-being Da Costa, B.R., & Vieira, E.R. (2010) Risk factors for workrelated musculoskel etal disorders: A systematic review of recent longitudinal studies Linton, S., J. (2001) Occupational Psychological factors increase the Information needed to help healthcare providers, ergonomists and researchers to design interventions to identify risk factors to help reduce the rate of workrelated musculoskelet al disorders SR of longitudinal studies to evaluate the evidence for risk factors for workrelated musculoskele tal disorders (WMSD) to be compared to NIOSH review findings Review of WMSD with only cohort & casecontrol studies, first evaluation of available evidence reviewing each body part identified Early identification of work related risk factors are needed to effectively SR of the role that psychological Workplace variables play in relation to Strong evidence that monotono us tasks , work relations, 15 shoulders & lower back were the most common injury sites affected Moderate evidence) (CI 1.72-4.43 for association of neck symptoms & female gender Greater than sitting in vehicle more than 10hr/wk, driving more than 20hr\wk & greater mileage Out of 63 studies, most frequently reported biomechanical identified risk factor with reasonable evidence for causal association with WMSD is excessive repetition, heavy lifting & poor postures 21 studies included prospective design studies, Randomized controlled trials, heavy bulky materials in & out of vehicles Age related physiological changes in the joints need consideration for reduction of injury Factors found without strong evidence need further investigation because WMSD’s may occur when the musculoskele tal system is pushed beyond physiological limit Level 1 A Incorporating knowledge of the role that psychological factors play at work, may enhance Level 1 B SR Cohort & case control studies utilized SR Prospective studies utilized risk for back pain: A systematic review improve treatment & help prevent a worker from developing long term back pain & associated disability This need is increased with age related physiological changes back pain Return to work, absenteeism, & injury was used as an outcome variable in half of the studies, injury considered from 2 studies job satisfaction stress, job demands & perceived work ability were related to future back pain problems evaluation studies, followup studies, comparative studies & clinical trials, Most clinical trials were excluded because they did not include data on a psychological predictor variable prevention and rehabilitation , injury information from 2 studies & questionnaire data collection were two limitations Attributable fraction- back pain reduction ranged from 0% regarding effect of pace on sick leave to greater than 7 days for females to 66% for satisfaction with job, majority in the upper 30s or lower 40s, This data suggests it is worthwhile to try to eliminate these risk factors Adapted from Blagojevic, M., Jinks, C., Jeffry, A., & Jordan, K.P. (2010). Risk factors for onset of osteoarthritis of the knee in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 18, 24-33. 16 Crawford, J.O., MacCalman, L. & Jackson, C. A. (2011). The health and well-being of remote and mobile workers, Occupational Medicine, 61, 385-394. Da Costa, B., & Vieira, E., R. Risk factors for work-related musculoskeletal disorders: A systematic Review of recent longitudinal studies, American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 53,285-323. Linton, S., J. (2001). Occupational psychological factors increase the risk for back pain: A systematic review, Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 11(1), 53-65. Guideline Developer Nancy Delloiacono, MSN, RN, Certificate in Primary Care of the Adult and Aged Nurse Practitioner Postmaster’s Program, Rutgers, The State University College of Nursing, ANP-BC, DNP student, Rutgers, The State University College of Nursing, 7 years of experience as an OHN Implementation Strategy- implemented through an online educational program for OHN members of the NJSAOHNs. Source of Funding-Rutgers University Alumni Association Fenlasen Award and Scholarship 17 Appendix A The CEBM 'Levels of Evidence 1' document sets out one approach to systematising this process for different question types. Level 1a 1b 1c 2a 2b Therapy / Prevention, Aetiology / Harm Prognosis SR (with SR (with homogeneity*) homogeneity*) of of RCTs inception cohort studies; CDR" validated in different populations Individual RCT Individual (with narrow inception cohort Confidence study with > 80% Interval"¡) follow-up; CDR" validated in a single population Diagnosis Differential diagnosis / symptom prevalence study SR (with SR (with homogeneity*) of homogeneity*) Level 1 diagnostic of prospective studies; CDR" with cohort studies 1b studies from different clinical centres Validating** cohort Prospective study with cohort study good" " " reference with good standards; or follow-up**** CDR" tested within one clinical centre Economic and decision analyses SR (with homogeneity*) of Level 1 economic studies Analysis based on clinically sensible costs or alternatives; systematic review(s) of the evidence; and including multiway sensitivity analyses All or none§ All or none case- Absolute SpPins and All or none Absolute betterseries SnNouts" " case-series value or worsevalue analyses """" SR (with SR (with SR (with SR (with SR (with homogeneity*) homogeneity*) of homogeneity*) of homogeneity*) homogeneity*) of cohort either Level >2 diagnostic of 2b and better of Level >2 studies retrospective studies studies economic cohort studies or studies untreated control groups in RCTs Individual Retrospective Exploratory** Retrospective Analysis based cohort study cohort study or cohort study with cohort study, or on clinically (including low follow-up of good" " " reference poor follow-up sensible costs or © 2014 Nancy Delloiacono, MSN, RN, APN-BC 1 quality RCT; e.g., <80% follow-up) 2c 3a 3b 4 5 untreated control patients in an RCT; Derivation of CDR" or validated on split-sample§§§ only "Outcomes" "Outcomes" Research; Research Ecological studies SR (with homogeneity*) of case-control studies Individual Case-Control Study Case-series (and poor quality cohort and casecontrol studies§§) Expert opinion without explicit critical appraisal, or based on physiology, standards; CDR" after derivation, or validated only on split-sample§§§ or databases Ecological studies SR (with SR (with homogeneity*) of 3b homogeneity*) and better studies of 3b and better studies Non-consecutive Nonstudy; or without consecutive consistently applied cohort study, or reference standards very limited population Case-series (and poor quality prognostic cohort studies***) Case-control study, poor or nonindependent reference standard Expert opinion without explicit critical appraisal, or based on physiology, bench research or Expert opinion Expert opinion without explicit without explicit critical appraisal, or critical based on physiology, appraisal, or bench research or based on "first principles" physiology, 2 Case-series or superseded reference standards alternatives; limited review(s) of the evidence, or single studies; and including multi-way sensitivity analyses Audit or outcomes research SR (with homogeneity*) of 3b and better studies Analysis based on limited alternatives or costs, poor quality estimates of data, but including sensitivity analyses incorporating clinically sensible variations. Analysis with no sensitivity analysis Expert opinion without explicit critical appraisal, or based on economic theory bench research "first principles" or "first principles" bench research or "first or "first principles" principles" Produced by Bob Phillips, Chris Ball, Dave Sackett, Doug Badenoch, Sharon Straus, Brian Haynes, Martin Dawes since November 1998. Updated by Jeremy Howick March 2009. Notes Users can add a minus-sign "-" to denote the level of that fails to provide a conclusive answer because: EITHER a single result with a wide Confidence Interval OR a Systematic Review with troublesome heterogeneity. Such evidence is inconclusive, and therefore can only generate Grade D recommendations. * " "¡ § §§ §§§ "" By homogeneity we mean a systematic review that is free of worrisome variations (heterogeneity) in the directions and degrees of results between individual studies. Not all systematic reviews with statistically significant heterogeneity need be worrisome, and not all worrisome heterogeneity need be statistically significant. As noted above, studies displaying worrisome heterogeneity should be tagged with a "-" at the end of their designated level. Clinical Decision Rule. (These are algorithms or scoring systems that lead to a prognostic estimation or a diagnostic category.) See note above for advice on how to understand, rate and use trials or other studies with wide confidence intervals. Met when all patients died before the Rx became available, but some now survive on it; or when some patients died before the Rx became available, but none now die on it. By poor quality cohort study we mean one that failed to clearly define comparison groups and/or failed to measure exposures and outcomes in the same (preferably blinded), objective way in both exposed and non-exposed individuals and/or failed to identify or appropriately control known confounders and/or failed to carry out a sufficiently long and complete follow-up of patients. By poor quality case-control study we mean one that failed to clearly define comparison groups and/or failed to measure exposures and outcomes in the same (preferably blinded), objective way in both cases and controls and/or failed to identify or appropriately control known confounders. Split-sample validation is achieved by collecting all the information in a single tranche, then artificially dividing this into "derivation" and "validation" samples. An "Absolute SpPin" is a diagnostic finding whose Specificity is so high that a Positive result rules-in the diagnosis. An "Absolute SnNout" is a diagnostic finding whose Sensitivity is so high that a Negative result rules-out the diagnosis. 3 "¡"¡ Good, better, bad and worse refer to the comparisons between treatments in terms of their clinical risks and benefits. " " " Good reference standards are independent of the test, and applied blindly or objectively to applied to all patients. Poor reference standards are haphazardly applied, but still independent of the test. Use of a non-independent reference standard (where the 'test' is included in the 'reference', or where the 'testing' affects the 'reference') implies a level 4 study. " " " " Better-value treatments are clearly as good but cheaper, or better at the same or reduced cost. Worse-value treatments are as good and more expensive, or worse and the equally or more expensive. ** Validating studies test the quality of a specific diagnostic test, based on prior evidence. An exploratory study collects information and trawls the data (e.g. using a regression analysis) to find which factors are 'significant'. *** By poor quality prognostic cohort study we mean one in which sampling was biased in favour of patients who already had the target outcome, or the measurement of outcomes was accomplished in <80% of study patients, or outcomes were determined in an unblinded, non-objective way, or there was no correction for confounding factors. **** Good follow-up in a differential diagnosis study is >80%, with adequate time for alternative diagnoses to emerge (for example 1-6 months acute, 1 - 5 years chronic) Grades of Recommendation A B C D consistent level 1 studies consistent level 2 or 3 studies or extrapolations from level 1 studies level 4 studies or extrapolations from level 2 or 3 studies level 5 evidence or troublingly inconsistent or inconclusive studies of any level "Extrapolations" are where data is used in a situation that has potentially clinically important differences than the original study situation 4 Appendix B Evidence to support this safety guideline Evidence to Support Safety Guideline to reduce the risk of musculoskeletal injury in older adults in the workplace Projected annual growth rate of older adults is 4.1% (Silverstein, 2008). Increased projected growth rate of older adults in the workforce is due to : deferring retirement, longer life expectancies, choosing a second career (Canning & Bloom, 2012) As proportions of older adults in the workforce increases, the impact of treating & associated costs will continue to increase (Foster et al, 20120). Due to the nursing shortage, organizations need to take every effort to safely retain older nurses. Only with the OHN and employer having comprehensive knowledge of agerelated changes and environmental accommodations, will the older adult nurse be able to work safely delaying retirement (Keller & Burns, 2010; Palmer, 2003). Age-related musculoskeletal changes place older adults at risk for injury (Foster et al, 2012; Perry, 2010; Bohle et al, 2010; Health status identified as a critical factor related to safety in the workplace (Keller & Burns, 2010; Perry, 2010). Chronic disease along with acute illness in older adults can adversely influence daily job performance & consequently cause increased risk of work-related safety in the workplace (Silverstein, 2008). Hearing problems affect approximately one third of our American population who are between age 65 and 74 (Perry, 2010 Dynamic visual acuity (DVA) deteriorates under age 60. If a job requirement involves visual acuity of highly mobile information or controls, this responsibility should probably be handled by a younger employee (Perry, 2010). Dynamic visual acuity (DVA) deteriorates under age 60. If a job requirement involves visual acuity of highly mobile information or controls, this responsibility should probably be handled by a younger employee (Perry, 2010). As proportions of older adults in the workforce increases, the impact of treating & associated costs will continue to increase (Foster et al, 2012). The aging process causes a progressive deterioration in every link in the oxygen transport chain. As a result, a decrease of maximum oxygen intake from about 45 ml\kg per minute found in young women to approximately 25-28 ml\kg in women 65 years of age occurs (Perry, 2010). Obesity compounds this issue. If an obese person is exercising, there is a greater need for skin blood flow which reduces arterial-venous oxygen difference (Sheppard, 1987) © 2014 Nancy Delloiacono, MSN, RN, APN-BC 1 According to Schrack et al, 2010), the hypothesis of a lack of available energy causing the decline in everyday walking speed with aging and disease has been validated. “The Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly (EPESE) found that lower baseline lower extremity performance scores were associated with increased frequency of mobility disability and dependence in one or more activities of daily living” (Schrack et al, 2012). “In the Women’s Health and Aging study (WHAS) 11, if women had difficulty walking half a mile, slowed walking speed or difficulty climbing stairs, these limitations predicted disability in older women. “(Schrack et al, 2010). Collectively, these two studies showed that physical performance, particularly walking speed, predicts the state of functional disability for the future (Schrack et al, 2012). If the older adult suffers from recurrent bronchitis or emphysema, vital capacity is not as good and the lungs must work harder to breath. An exercise physiologist may be needed to coach exercise tolerance (Sheppard, 1987). Muscle mass changes which occur with the aging process, causes an older adult to have more difficulty lifting heavy objects and participating in prolonged repetitive tasks (Keller & Burns, 2010). Fine motor skills, manual dexterity and tactile sensations decline as we age (Perry, 2010) Decrease in flexibility, has been linked to loss of balance and strength, improper posture, restricted movements, slower injury recovery and stress (Perry, 2010). The amount of cells being replaced with fat tissue is determined by the amount the muscle is exercised, diet and prevalence of disease and injury (Perry, 2010). Chronic pain, most expensive problem for US Workers Compensation costing $14 million\year (Vieira & Kumar, 2006) Osteoporosis decreases while low bone mass does not (Bone & Joint Initiative, 2011). Muscle strength & neuromuscular function can impact vitamin D deficiency (Bone & Joint, 2011). Weight loss may not be considered a red flag because it may be related to musculoskeletal disorders (Foster et al, 2012). Age related changes, underlying pathologies, acute health issues and chronic disease in workers beginning at age 45, can affect everyday task performance and lead to an increased risk of work-related injuries (Keller & Burns, 2010). #1 injury found in the 2007 Liberty Safety Index (LSI) is overexertion injury (Liberty Mutual, 2007). 70 % of low back injuries result from overexertion and manifest themselves as tears, sprains & strains (Viera & Kumar, 2006). In comparison to other musculoskeletal injuries, shoulder injuries have the longest average recovery time (Dickerson et al, 2010). 2 Strategies to help lower company costs incurred by medical claims & to decrease worker compensation injury: employee education on health improvement & managing chronic illness (Keller & Burns, 2010). Once an older worker is inflicted with a disability, they will need more time to convalesce and return to work than a younger worker (Keller & Burns, 2010; Silverstein, 2008). Older workers document less disability incidents than younger workers, especially incidents resulting from musculoskeletal injuries (Keller & Burns, 2010). In order of occurrence, types of muscular pain areas encountered are low back, shoulder, neck, knee & widespread complaint of pain (Foster et al, 2012). Early treatment by physical therapists for commonly suffered musculoskeletal problems reduces the amount of lost time & decreases chances of progression to chronic illness (Foster et al, 2012). For low back & shoulder pain, there can be a relationship between low variation & low satisfaction with the job (Guara, 2002). Force exertion utilizing the back muscles such as lifting heavy weights can result in precipitation of low back injury (Vieira & Kumar, 2006). Workers perceptions of stresses encountered in lifting a load may not be reliable enough to protect workers from back injury (Vieira & Kumar, 2006). Lifting 35 pounds or more & lifting more than the horizontal distance of 20 inches from the person’s ankle increases the risk of injury (Chaffin & Park, 1973). Low back pain cost-effectiveness data found during random clinical trials shows costeffectiveness only occurs with addition of behavioral counseling, exercise & chiropractic care (Foster et al, 2012). Clinical outcomes poorer in individuals experiencing depression along with chronic musculoskeletal pain (Foster et al, 2012). Early treatment by physical therapists for commonly suffered musculoskeletal problems reduces the amount of lost time & decreases chances of progression to chronic illness (Foster et al, 2012). Primary prevention of many chronic diseases has been demonstrated with the addition of regular intentional exercise to healthy living (Neilson et al, 2007). In comparison to other musculoskeletal injuries, shoulder injuries have the longest average recovery time (Dickerson et al, 2010). The amount of the cells being replaced with fat tissue is determined by the mount the muscle is exercised, diet and prevalence of disease and injury (Perry, 2010). Decrease in flexibility, has been linked to loss of balance and strength, improper posture, restricted movements, slower injury recovery, and stress (Perry, 2010). 3 Older adults who participate in regular intentional exercise is key to maintaining good health. Primary prevention of many chronic diseases such as cardiovascular, type 2 diabetes, osteoporosis and a number of cancers, has been demonstrated with the addition of regular exercise to healthy living (Neilson et al, 2007). Ergonomic Evidence Keep in mind the principals of how low physical effort, flexibility & simple design to improve workplace safety (Silverstein, 2008). There is a strong musculoskeletal injury association with psychosocial factors. How well a worker gets along with his/her boss can have a significant influence on recovery & the prevalence of injury (Bohle et al, 2010). To increase ergonomic intervention success, reduce work physical demands (Vieira & Kumar, 2006). Ergonomic committees-Employers and OHNs need to identify work hazards, find solutions, raise awareness, educate and modify the environment for older workers to increase safety and support the needs of the older worker (Bloom & Canning, 2012; Perry, 2010; Leggert, 2012). There is no recommendation to sit or stand. Both have advantages and disadvantages. If an individual alternates postures, it will give the body time to rest specific body parts and reduce the potential to develop risk factors commonly associated with the development of musculoskeletal disorder s (UCLA Ergonomics, n. d.). “The maximum reach envelop when standing is significantly larger than the corresponding reach envelop when sitting for both men and women (Sengupta & Das, 2000). In a study by Vieira et al (2012), it was found that workers surveyed in an automobile industry showed strong evidence between Kaizen and ergonomics. Due to the nursing shortage, organizations need to take every effort to safely retain older nurses. Only with the OHN and employer having comprehensive knowledge of agerelated changes and environmental accommodations, will the older adult nurse be able to work safely delaying retirement (Keller & Burns, 2010). The reduced physical activity that results in sitting all day on the job (Sitting Disease) increases the risk of cardiovascular disease. Exercising outside of work does not reduce the damage of sitting all day at work (AHA, 2008; ACSM, 2011). Exercise increases cognitive performance which in turn increases productivity (McCraty et al, 2006). Less active workers are 30-50% more at risk of developing hypertension (CDC, 2008). 4 Repetitive movement with motions that occur often for long periods of time may cause insufficient time for muscles & tendons to rest & recover. Combined with activities requiring concentrated force can lead to stiffness & pain indicating that the muscle or tendon has been stretched beyond its capacity (OSHA, n. d.). Finding solutions to task organization & heightening awareness to early warning signs can reduce risk of developing musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) & eliminate the chances of injury (OSHA, n. d.). Prevention To prevent further deterioration of arthritic disorders: encourage adherence to medications, adequate rest & sleep, educate on ice and heat Interventions to help prevent work-related musculoskeletal disorders should take into account not only risk factors with strong evidence but those suppose risk factors should also be addressed (daCosta & Vieira, 2010). There is strong evidence that the following occupational psychological factors increase the risk of future complaints of back pain- low job satisfaction, monotonous work, social work relations, work pace, lack of control, self- reported stress, work demand, emotional effort and perceived ability to work (Linton, 2001). To prevent low bone mass, recommend bone density testing according to national guidelines, encourage regular exercise with low impact on joints such as walking & swimming To prevent spinal injury, instruct on proper body mechanics, strengthening exercise & regular exercise Educate on strength training, balance, gait exercises, flexibility endurance (Seidel et al, 2011). Yoga encourages reduction of work-related tension & injury risk (Guara, 2002). General health maintenance should include proper nutrition, adequate calcium intake, adequate intake of water (eight (8) glasses), regular activity & exercise, stress management techniques: if possible, reduce job demands, offer corporate exercise and stress management programs, employee assistance program referrals. Localized fatigue results from uninterrupted contraction of muscles (Lindstrom et al, 1977). Workers perceptions of stresses encountered in lifting a load may not be reliable enough to protect workers from back injury (Vieira & Kumar, 2006). 5 Appendix C References Agnew, J., Slade, M., Cantley, Taiwo, O., Vegso, S., Sircar, K., & Cullen, M.R. (2007). Use of employer administrative databases to identify systematic causes of injury in aluminum manufacturing, American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 50, 676-686. Alipour, A. et al. (2008). Occupational neck and shoulder pain among automobile manufacturing workers in Iran. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 51, 372-379. doi: 10.1002/ ajim.20562. American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine Clinical Practice and Guideline Center (2009). Guidelines for common health problems and functional recovery in workers, healthy workforce now American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine (ACOEM), Retrieved from http://www.acoem.org/PracticeGuidelines.aspx. Blagojevic, M., Jinks, C., Jeffrey, A., & Jordan, K.P. (2010). Risk factors for onset of osteoarthritis of the knee in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis, Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 18, 24-33. Braddock, E. J., Greeniee, J., Hammer, R. E., Johnson, S. F, Martello, M. J., O’Connell, M .R., Rinzler, R. Snider, M., Swanson, M. R., Tain, L. Walsh, G. Manual Medicine Guidelines for Musculoskeletal Injuries. Sonora (CA): Academy for Chiropractic Education, (2009), 64,214Cassou, B., Derriennic, F., Monfort, C., Norton, J., & Thouranchet, A. (2002). Chronic neck and shoulder pain, age, and working conditions: longitudinal results from a large random sample in France, Occupational Environmental Medicine, 59, 537-544. © 2014 Nancy Delloiacono, MSN, RN, APN-BC i Crawford, J.O., MacCalman, L., & Jackson, C.A. (2011). The health and well-being of remote and mobile workers, Occupational Medicine, 61, 385-394. Culp, K., Tonelli, S. & Ramey S. (2011). Gerontological nursing and the aging workforce,. Gerontological Nursing, 1, 87-96. DaCosta, B., & Vieira, E., R. (2010). Risk factors for work-related musculoskeletal disorders: A systematic review of recent longitudinal studies, American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 53, 285-323. Harris, J. L., Roussel, J., Walters, S. E., & Dearman, C. (2011). Project planning and management: A guide for CNLs, DNPs, and nurse executives. MA: Jones and Bartlett Learning. Harvey, P. & Thurnwald, I. (2009). Aging well, ageing productively: The essential contribution of Australia’s ageing population to the social and economic prosperity of the nation, Health Society Review, 18, 379-793. Hillstrom, K. & Hillstrom, L.C. (Eds.). (2002). Corporate Culture. The Encyclopedia of Small Business, (pp. 254-255). Gale Group. James, J.B., Besen, E., Matz-Costa, C. & Catsouphes-Pitt, M. (2012). Just do it?..maybe not! Insights on activity in later life from the Life and Times in an Aging Society Study. Chestnut Hill, MA: Sloan Center on Aging & Work, Boston College. Kaskutas, V., Snodgrass, J. (2009). Occupational therapy practice guidelines for individuals with work-related injuries and illnesses. Bethasda, MD: American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA), 176. Retrieved from http://www.guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=15288. Keller, S.M. & Burns, C.M. (2010). The aging nurse: Can employers accommodate age-related ii changes? AAOHN, 58, 437-445. Kowalski-Trakofler, K., Steiner, L., J., & Schwerha, D.J. (2005). Safety considerations for the aging workforce, Safety Science, 43, 779-793. Lach, H.W., Everard, K. M., Highstein, G. & Brownson, C. A. (2004).Application of the transtheoretical model health education for older adults. Health Promotion Practice, 5, 88-93. Langley, G., Moen, R. Nolan, K. Nolan, T. Norman, CI, Provost, L. (2010). The improvement guide,( 2nd Ed.). CA: Jossey Bass. Leggert, D. (2007).The aging workforce: Helping employees navigate midlife. Business and Leadership, 55, 169-175. Leino, P. & Hanninen, V. (1995). Psychosocial factors at work in relation to back and shoulder disorders. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment and Health, 21, 134-142. Liggins, C., Pryor & Bernard, M. A. (2010). Challenges and opportunities in advancing models of care for older adults: An assessment of the national institute of aging research portfolio. JAGS, 58, 2345-2349. Linton, S., J. (2001). Occupational psychosocial factors increase the risk of back pain: A systematic review, Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 11(1), 53-65. Lipscomb, H .J., & Silverstein, B. (2008). Incident & recurrent back injuries among union carpenters, Occupational Environmental Medicine, 6, 827-834. N.A. (2010) Executive case summary series, health and wellbeing: And the prism of age. Chestnut Hill, Ma: Sloan Center on Aging & Work, Boston College. Goldfried, M. R. (2005). The Handbook of Psychotherapy Integration 2 nd. iii ed. New York: Oxford University Press. Noy, Y.I., (2008). Workplace safety index, Looking back: Origins of a national metric. From Research to Reality, Liberty Mutual, 11, 1-6. O’Connell, M. & Delgado, K. (2011). Safer hiring, Industrial Management, 24-30. Occupational Safety & Health Administration (OSHA) and US Department of Labor. (2008) Guidelines for shipyards: Ergonomics for the prevention of musculoskeletal disorders. Retrieved from http://www.osha.gov/Publications/OSHA3341/shipyard Perry, L. (2010). The aging workforce: using ergonomics to improve workplace design. Professional Design, 22-28. Reinsborough, P. & Canning, D. (2010). Re:imaging change-how to use story-based strategy to win campaigns, build movements and change the world. CA: P.M Press. Safety Compliance Letter, Can behavior-based safety work in today’s environment? Aspen Publishers, July 2009, issue 2503. Salonen, P.H., Arola, H., Nygard, C., & Huhtala, H. (2008). Long term associations of stress and chronic diseases in ageing and retired employees, Psychology, Health & Medicine, 13, 55-62. Seidel, H.M., Ball, J. W., Dains, J.E., Flynn, J.A., Solomon, B.S., & Stewart, R.W. (2011). Mosby’s Guide to Physical Examination, 7th Ed. Mo: Mosby Elsevier. Sheehy, G. (1995). New Passages, NY: Banantine Books, Silverstein, M. (2008). Meeting the challenges of an aging workforce. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 51, 269-280. Sloan Center on Aging and Work, Boston College. (2012). Aging today: Some questions iv about health, Fact Sheet 30. Retrieved from http://www.bc.edu/agingandwork. Smith, C., M., & Cotter, V., Capezuti, E., Zwicker, D., Mezey, M., Fulmer, T. Eds. (2008). Age related changes in health, In: Evidence-based Geriatric Nursing Protocols for Best Practice. 3 rd Ed. New York : Springer Publishing Company, 431- 58. Retrieved from http://www. guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=12250&search=musculoskeletal+injury+preven… United States Bone and Joint Initiative: The Burden of Musculoskeletal Diseases in the United States, Prevalence , Societal and Economic Cost, 2nd Ed., Rosemont, Il: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 2011. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2004). Retrieved from www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/osh10252012. W.K., Kellogg Foundation (2004). Logic Model Development Guide, Battle Creek, Michigan. Retrieved from www.wkkf.org . v