MA Professional Standards for Teachers ESOL

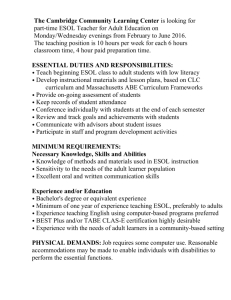

advertisement