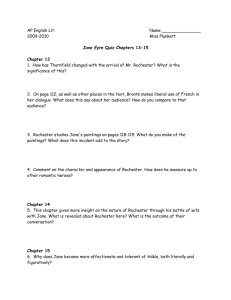

Literary Essay on Jane Eyre

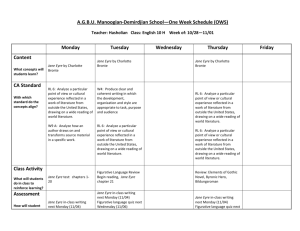

advertisement

Oberlander 1 Hannah J. Oberlander May 11, 2014 HIST 635 The Subtleties and Defiance of British Culture Within the Pages of Jane Eyre Published in 1847, Jane Eyre illuminates for modern readers the culture of Victorian England by subtly integrating the then-current British stereotypes of gender and imperialism throughout the pages of this novel. Authoress, Charlotte Bronte—cloaked under the pseudonym Currer Bell—wrote both with and against various Victorian social trends as she penned the plot of a young, middle-class governess named Jane Eyre. Eyre goes to work at Thornfield Hall, an eerily curious mansion owned by Master Edward Rochester. Bronte portrays Rochester as a supposed bachelor whose wealth was obtained through business ventures in mysterious foreign lands throughout the Empire. Rarely frequenting the home, Rochester leaves his French daughter under the tutelage of Eyre, a woman whose unjust upbringing has her questioning, rather than accepting the Victorian norm for women to be dependent upon men in society. Attracted to Eyre’s independent spirit and unwavering nature of care and concern for others, Rochester asks Eyre to marry him despite the Victorian social norm of not dipping into the lower classes. No sooner had their wedding ceremony commenced, when Eyre comes to find out that Rochester is still married to another woman––an unthinkable Victorian social taboo. Bronte challenges this Victorian taboo by building empathy for Rochester when she explains to her readers that years before, Rochester had been tricked into marrying a mad woman in the West Indies whom would normally have been confined to an insane asylum. Out of duty—a celebrated Victorian ideal—Bronte explains that Rochester has overseen his mad wife’s care for the past ten years in a secret chamber on the third floor of his large home. Given these extenuating circumstances, Rochester is convinced that a decent marriage never had existed between them, since her mental state was unbearably extreme. Devastated by this shocking revelation, Eyre flees Rochester’s Thornfield with no money and nearly starves to death before she is taken in by a middle class family. Devout Christians, the Rivers family treat Eyre as if she is one of their own. While Eyre stays with the Rivers, she inherits a large sum of money from a long-lost uncle and is proposed to for marriage by St. John Rivers, a determined British missionary seeking to follow God’s calling to go to Oberlander 2 the Empire’s colony of India. Yet, now that Eyre has the ability to make her own independent choices with her newly inherited wealth, she rejects St. John’s marriage proposal and feels compelled to return to Thornfield, where she learns that Rochester’s insane wife has burned a large portion of the house. Eyre finds out that Rochester himself was badly injured in the fire when he attempted unsuccessfully to rescue his wife from committing suicide. Eyre chooses to devote herself to taking care of the blinded Rochester, who has remained in love with her, and Eyre decides to stay with him at his Thornfield estate. On her own accord, Eyre marries Rochester, whose sight slightly recovers, and they start a family of their own together. Bronte depicts four different types of women in Jane Eyre—each of who reflect the Victorian culture and British imperialist prejudice common to the Empire during the mid-1800s. Specifically, these women are: the French woman, the savage woman, the ideal British woman in Victorian society, and the atypical Jane Eyre herself, who stakes out her claim throughout the pages of the novel as she defies the middle class woman’s “proper place” implicitly through her actions. When Rochester expresses to Eyre his relationship with Celine Varens, his French daughter’s mother, his explanation epitomes British sentiments about French women during this time. Varens, a French opera-dancer, had manipulated Rochester into thinking that she loved him. Despite her passionately charming words, Rochester had found Varens in bed with a French soldier, whom he views as the opposite of himself: “brainless and vicious youth.” 1 Rochester admits that “a woman who could betray me for such a rival was not worth contending for: she deserved only scorn; less, however, than I, who had been her dupe.”2 Rochester even wonders if her child, Adele, is his own, because of Varens’ flagrant promiscuity. Showing the superiority of British decency, Rochester explains to Eyre that the illegitimate child, whom is her protégée, was then abandoned by her conceited French mother. Subsequently, Bronte suggests that Rochester is the savior of the poor abandoned girl, and she describes 1 Brontë, C., Eichenberg, F., Rogers, B., Heritage Press (New York, N.Y.), & Pforzheimer Bruce Rogers Collection (Library of Congress). (1943). Jane Eyre. New York: Random House, p. 86. 2 Brontë, C., Eichenberg, F., Rogers, B., Heritage Press (New York, N.Y.), & Pforzheimer Bruce Rogers Collection (Library of Congress). (1943). Jane Eyre. New York: Random House, p. 86. Oberlander 3 how he “took the poor thing out of the slime and mud of Paris, and transplanted [her] here, to grow up clean in the wholesome soil of an English country garden.”3 In addition, he alludes to the French superficiality and obsession with riches when he says about Varens that “she charmed my English gold out of my British breeches’ pocket . . . [I] gave her a complete establishment of servants, a carriage, cashmeres, diamonds, dentelles, etc.”4 Rochester’s remarks verbalize how the British viewed French women during this era as bewitching adulteresses, whom—as Linda Colley puts it—mirror the image of Marie Antoinette, whose “reputed corruption, infidelities, lesbianism and incest with her son”5 detested the upright and honorable British woman of the day. The fear of a barbarian French invasion only heightened the biased perception of the French culture within British culture. In contrast, the superior British military heroes brought women a sense of security during these troubled times—like the well-known Duke of Wellington—who captured the imagination of England’s young girls of the day including Bronte herself. Colley paraphrases Rebecca Fraser when she writes: Charlotte Bronte for one was a fervent admirer of the Duke of Wellington from when she was five years old . . . [and] was the germ from which the dark and masterful Mr. Rochester of Jane Eyre would ultimately be created.6 Idolized British heroes created a sense of security and were, in many ways, the fantasized rescuers of British women who wished to be protected from the morally corrupt French—much like Adele is rescued from French culture by Rochester when he chooses to care for her in England. Female readers of Bronte’s first edition were also hungry for a perception of themselves as more moral and proper than the scandalous French women of the day. Bronte uses the character of Bertha Mason, Rochester’s deranged wife, to subtly reveal how British society perceived savages from exotic lands under British imperial rule. Depicted as from 3 Brontë, C., Eichenberg, F., Rogers, B., Heritage Press (New York, N.Y.), & Pforzheimer Bruce Rogers Collection (Library of Congress). (1943). Jane Eyre. New York: Random House, p. 87. 4 Brontë, C., Eichenberg, F., Rogers, B., Heritage Press (New York, N.Y.), & Pforzheimer Bruce Rogers Collection (Library of Congress). (1943). Jane Eyre. New York: Random House, p. 84. 5 Colley, L. (1992). Britons: Forging The Nation, 1707-1837. New Haven: Yale University Press, p. 261. 6 Colley, L. (1992). Britons: Forging The Nation, 1707-1837. New Haven: Yale University Press, p. 264. Oberlander 4 Spanish Town, Jamaica, Bronte introduces the woman to the reader through Jane Eyre’s own eyes when she says: What it was, whether beast or human being, one could not, at first sight, tell: it groveled, seemingly on all fours; it snatched and growled like some strange wild animal: but it was covered with clothing; and a quantity of dark, grizzled hair, wild as a mane, hid its head and face.7 This correlates with the animalistic “savage” image that many British people identified with the inferior races from places like Africa, India, Australia, and the West Indies. Brantlinger writes about this imperialist perception when he comments that “presumably, everyone is a link somewhere in this late Victorian version of the great chain of being: if gentlemen are . . . the farthest remove[d] from our anthropoid ancestors, the working class is not so far removed, and ‘savages’ are even closer.”8 Rochester verbalizes about his alleged wife that she “is mad; and she came of a mad family; —idiots and maniacs through three generations! Her mother the Creole, was both a mad woman and drunkard.”9 Bronte makes Rochester the hero yet again with the savage woman when he attempts to save her life—despite her degenerative state—when she sets fire to his home. Savage ignorance and lack of rationality can be interpreted from the scene, where Bronte dramatically has Rochester charge after his senseless wife on the roof to plead with her to come with him to safety; yet, she jumps to her death as her “brains and blood were scattered” below.10 The ideal Victorian woman of Charlotte Bronte’s world was one of refined dignity played out in homebound femininity. Jane Eyre herself is well-versed in the notion that British womanhood encapsulated “domestic values in middle-class culture,”11 and she—like all women of her day—was told that “a stable family [w]as the way to achieve not only social harmony but also individual fulfillment.”12 From her very entrance to Lowood School as a young girl, obedience, submission, and order were the 7 Brontë, C., Eichenberg, F., Rogers, B., Heritage Press (New York, N.Y.), & Pforzheimer Bruce Rogers Collection (Library of Congress). (1943). Jane Eyre. New York: Random House, p. 176. 8 Brantlinger, P. (1985). Victorians and Africans: The Genealogy of the Myth of the Dark Continent. Chicago: University of Chicago, p. 186. 9 Brontë, C., Eichenberg, F., Rogers, B., Heritage Press (New York, N.Y.), & Pforzheimer Bruce Rogers Collection (Library of Congress). (1943). Jane Eyre. New York: Random House, p. 176. 10 Brontë, C., Eichenberg, F., Rogers, B., Heritage Press (New York, N.Y.), & Pforzheimer Bruce Rogers Collection (Library of Congress). (1943). Jane Eyre. New York: Random House, p. 258. 11 Davidoff, L., & Hall, C. (2002). Family Fortunes. London: Routledge, p. 179. 12 Davidoff, L., & Hall, C. (2002). Family Fortunes. London: Routledge, p. 180. Oberlander praised values of womanhood, whose moral responsibility was to one day “gratify the senses of man” by remaining the weaker vessel, of which Providence had intended.13 Fueled by the model of the biblical Proverbs 31 woman that prologues Mrs. Beeton’s Book of Household Management14 and by the virtuously superior heart of Coeleb’s bride from the pages of Hannah More’s popularly read novel,15 a woman’s true value was purity of heart and purpose within the home. Hence, Miss Temple—a kindhearted teacher from Jane’s childhood days at Lowood—embodies these submissive characteristics when she defers to the headmaster Mr. Brocklehurst and carries out his orders without question. Mild mannered and “motherly,” Miss Temple often sees the girls’ side on matters that are unfair and tries to encourage them to be strong despite their mistreatment by Brocklehurst. Yet, when push comes to shove, Temple is powerless to stand up to Brocklehurst—as he wields patriarchal powers common in British culture—and the girls are punished anyway.16 Her submission and virtuous qualities are eventually rewarded with the crowning glory of marriage. Jane speaks of Temple fondly when she says: To her instruction I owed the best part of my acquirements; . . . she stood me in the stead of mother, governess, and latterly, companion. At this period she married, removed with her husband (a clergyman, an excellent man, almost worthy of such a wife) to a distant county, and consequently was lost to me.17 For a woman in Victorian England, Miss Temple had achieved “feminine security . . . the legacy of conscious adaptation to the role of Perfect Wife.”18 But for Jane, she found herself in society’s worst place in which Dangerfield confesses that for “the unmarried woman . . . everything was denied her. [higher] education, business, love—all were impossible . . . . When a husband is a woman’s career, the woman without a husband is as good as dead.”19 13 Wollstonecraft, M. (1992). A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. Beeton, ., & Humble, N. (2000). Mrs Beeton's Book of Household Management. New York: Oxford University Press. 15 Davidoff, L., & Hall, C. (2002). Family Fortunes. London: Routledge, p.168. 16 Brontë, C., Eichenberg, F., Rogers, B., Heritage Press (New York, N.Y.), & Pforzheimer Bruce Rogers Collection (Library of Congress). (1943). Jane Eyre. New York: Random House, p. 39. 17 Brontë, C., Eichenberg, F., Rogers, B., Heritage Press (New York, N.Y.), & Pforzheimer Bruce Rogers Collection (Library of Congress). (1943). Jane Eyre. New York: Random House, p. 49-50. 18 Dangerfield, G. (1961). The Strange Death of Liberal England. New York: Capricorn Books. 19 Dangerfield, G. (1961). The Strange Death of Liberal England. New York: Capricorn Books. 14 5 Oberlander 6 Through her novel, Charlotte Bronte gave unimaginable hope to the women of her day, who were trapped in this stifling world of male dominance as she used Jane Eyre’s voice to resonate through the hearts and minds of her British readers. Jane does not shy away from pointing out the glaring inconsistencies in British culture and exposing the ideas that women could have the ability to do more and be more than what society currently offered them in 1847. In Eyre’s Feminist Manifesto20—a term penned by literary scholars of Bronte’s work—she reveals to her readers: Women are supposed to be very calm generally but women feel just as men feel; they need exercise for their faculties, and a field for their efforts as much as their brothers do; they suffer from too rigid a constraint, too absolute a stagnation, precisely as men would suffer; and it is narrow-minded in their more privileged fellow-creatures to say that they out to confine themselves to making puddings and knitting stockings, to playing on the piano and embroidering bags. It is thoughtless to condemn them, or laugh at them, if they seek to do more or learn more than custom has pronounced necessary for their sex.21 From the first few pages, Jane Eyre exerts her independent spirit as she defends herself as a young girl to Mr. Brocklehurst at Lowood. Bronte carries these ideas of feminine independence into Eyre’s adulthood when she articulates her honest opinion to Rochester in one of their initial conversations, which ignites his interest in Jane—as she is vastly different from most women Rochester has come into contact with. Rochester expresses to Jane, “There is something singular about you . . . you have the air of a little nonnette; quaint, grave, and simple. . . and when one asks you a question, or makes a remark to which you are obliged to reply, you rap out a round rejoinder, which if not blunt, is at least brusque.”22 Jane Eyre does not hesitate to assert her intelligence and her equality as she defies the stereotypical female norms of British culture. This is exposed in her response to Rochester’s marriage proposal when she passionately evokes: Do you think I am an automaton? –a machine without feelings? . . .Do you think, because I am poor, obscure, plain, and little, I am soulless and heartless? You think wrong! –I have as much soul as you, --and full as much heart! And if God had gifted me with some beauty, and much wealth, I should have made it as hard for you to leave me, as it is now for me to leave you. I am not talking to you now through the medium of custom, conventionalities, or even of mortal flesh: 20 Winter, K. J. (1992). Subjects of Slavery, Agents of Change: Women and Power in Gothic Novels and Slave Narratives, 17901865. Athens: University of Georgia Press, p. 93. 21 Brontë, C., Eichenberg, F., Rogers, B., Heritage Press (New York, N.Y.), & Pforzheimer Bruce Rogers Collection (Library of Congress). (1943). Jane Eyre. New York: Random House, p. 65. 22 Brontë, C., Eichenberg, F., Rogers, B., Heritage Press (New York, N.Y.), & Pforzheimer Bruce Rogers Collection (Library of Congress). (1943). Jane Eyre. New York: Random House, p. 78. Oberlander 7 --it is my spirit that addresses your spirit; just as if both had passed through the grave, and we stood at God’s feet, equal, --as we are!23 Jane Eyre appears to echo the words of Mary Wollstonecraft, the staunch feminist voice of the day, who argued that keeping the female half of society under subjection to man was a misrepresentation of Scripture. Wollstonecraft contended that woman, like man, had a soul and thus was accountable to God.24 Like Jane, Wollstonecraft challenged the typical British culture and articulated that women too were born with spiritual rights and consequently were not inferior to man.25 Fully aware that her ideas would be criticized for creating a character so bold as Jane Eyre, Bronte chose to write under the male pseudonym of Currer Bell, so that the British people would read her work with less prejudice. Jane Eyre further defies British norms when she only chooses to marry Rochester when he is in need of her after the fire as he is blinded, injured, and in want of care. Instead of marrying for protection, wealth, or security—all reasons most British women married for—Jane marries for love. Bronte overturns the British norm and ends the novel with Jane in the role of the rescuer when she marries Rochester because she has something to offer him rather than the other way around. Dangerfield captures Jane Eyre’s significance when he psychoanalyzes the status of women within the British culture of the 1800s and writes, “[s]ometimes a Charlotte Bronte would dip her pen in passion instead of ink and scandalize the world with some scorching revelation of her complicated soul.”26 Despite subtly alluding to the biases abroad about the stereotypical French persona and the savage identity of the imperialist frontier, Bronte daringly does something different with the character of Jane Eyre. Defying to place her heroine within the contemporary Victorian norms of a woman’s subjection at home, Bronte enlightens her readers through the character of Jane, declaring that they—as women—have an independent spirit within and can boldly stand up for themselves, not allow society to keep them down. 23 Brontë, C., Eichenberg, F., Rogers, B., Heritage Press (New York, N.Y.), & Pforzheimer Bruce Rogers Collection (Library of Congress). (1943). Jane Eyre. New York: Random House, p. 152. 24 Wollstonecraft, M. (1992). A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 25 Wollstonecraft, M. (1992). A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 26 Dangerfield, G. (1961). The Strange Death of Liberal England. New York: Capricorn Books.