“A Holy Ground Experience” Exodus 3:1

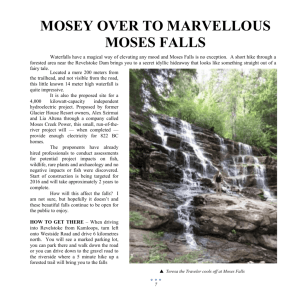

advertisement

“A Holy Ground Experience” Exodus 3:1-15 – August 28, 2011 INTRO: Last Sunday’s baby Moses in the basket has matured into an adult Moses, now a shepherd watching over his father-in-law’s flocks. The intervening chapters of this story tell about Moses being raised in the Pharaoh’s house, and a grown up Moses killing an Egyptian for beating a Hebrew slave. Fearing for his own life, Moses leaves Egypt, ending up in Midian, on the east side of the Dead Sea. There he defended a group of women who had come to draw water for their flock, from a well and were being driven away by some shepherds who thought the water should be all theirs. Out of that encounter, Moses met the man who would become his father-in-law, marries his daughter Zipporah, and they have a son. Today’s reading is part of the call of Moses, to go back to Egypt and lead the Israelite people to freedom. There’s enough fodder here for a month of sermons, but we only have today, so I’ll just work from a little part of it. Last Spring members of our Confirmation class were visiting the Islamic Center, on the south side of Milwaukee. We were getting ready to enter their worship space, and were invited to leave our shoes in the little cubbyholes along with everyone else’s shoes. People remove their shoes as a sign of reverence and respect for the holy space, and to show their devotion to God. In addition, in many mosques there are beautiful rugs on the floor, so it keeps those rugs from getting dirty and worn. In Jewish synagogues, and especially in Orthodox synagogues, we find men and sometimes women, wearing a yarmulke—a small cap. This is to fulfill the requirement that the head must be covered at all times. The yarmulke is a reminder that the Divine presence is always over one’s head and that there is One who is greater than we. It’s a way of honoring God, showing respect. Some of us here can probably remember a time when women didn’t enter Roman Catholic churches in our communities, without their heads being covered. “In Eastern Europe we still find centuries old Orthodox cathedrals and churches, which are both popular tourist attractions and sacred places. The specifics of what attire is acceptable vary. In Orthodox churches men must not have their heads covered, but in some, women are required to cover their heads. Men must also wear long pants and keep their hands out of their pockets, while women need long skirts or pants and a shirt with sleeves. Sometimes there are specific conduct requirements—visitors to Buddhist temples must always walk around in a clockwise direction and feet must never be pointed toward the altar or an image of Buddha.” (Homiletics, 8/11) In Whiteshell Provincial Park in Manitoba, Canada there is a spot that visitors are asked respect, where petroforms have been created by First Nations people—rocks that have been arranged to outline shapes of figures, like turtles, snakes, humans, a sweat lodge. For First Nations people, these places are sacred—the place for them where God sits. They serve as physical reminders of the instructions that have been given to their people by the Creator. Some of these rock forms have been in place for 1500 years. Visitors are asked to treat the place with respect. When First Nations people come to the place, the women cover their shorts with skirts, before walking the trail to the petroforms. “Whether it’s heads covered or uncovered, shoes on or off, or some other dress or behavioral requirement, the principle is the same. The holiness of the space is to be respected. That’s not difficult to understand, and most of us willingly cooperate. It’s perhaps not as clear that we might recognize a place as holy, if it’s not been designated—like the site of the burning bush on Mt. Horeb.” (Homiletics, 8/11) Horeb is described as beyond the wilderness—way out, remote. “As the story goes, Moses was on that mountain tending his father-in-law’s flock when he saw the bush blazing but not burning up. As he moved toward it, God spoke to him out of the bush, saying: ‘Come no closer! Remove the sandals from your feet, for the place on which you are standing is holy ground!’” (vs.5) Horeb is also known as Mt. Sinai, which may sound familiar to us, because that’s where Moses received the ten commandments. Because of what took place there, Horeb/Mt. Sinai “became known as the mountain of God—its status as a spiritually liminal place long recognized” through the experiences of God with God’s people. (Homiletics, 8/11) “In the ancient world, mountaintops were the traditional dwelling places for the divine.” (Dennis Olson) On Mt. Horeb, Moses encounters God through the presence of an angel, a bush that burns but isn’t burned, and a voice—probably not common, everyday experiences for many of us. And interestingly, “Moses’ encounter with God takes place far removed from the sights and sounds of the religious community. There is no temple nearby and no sign that this is a holy place. Unlike his father-in-law, Moses is not a priest or a prophet; it is an ordinary, everyday journey for him with no ‘religious’ intentions. The ground is now holy because of God’s appearance. Nature serves as an instrument for the divine presence and purpose. And because of the change in character of the place, Moses is asked to follow the custom of removing shoes to show respect.” (Dennis Olson) The idea that Moses was just going about his ordinary tasks, is good news for us, because it says that God’s presence, the holy, can break into our world too—even in the midst of the very ordinary. If you’ve been around long enough, your ideas about Moses may have been formed by watching Charlton Heston play Moses in that 1956 version of The Ten Commandments. “To this day, try as I might, I cannot shake the mistaken conception that God makes Godself known to ordinary human creatures like myself only in proportions worthy of Cecil B. DeMille—with the parting of vast seas, or through dreadful plagues, or by speaking from burning bushes. If we are professing here a God who will be whatever God will be, and this in response to particular circumstances in time and space, then this seems to provide a little more breathing room for those of us who cannot imagine that we will ever encounter a miracle of nature like a burning bush. The fact that Moses approached the spectacle with bare feet is a great comfort to me as well, because it suggest that while this theophany surely issues from heaven, its holiness can be found only on the lowly ground where it becomes known, in the dust beneath our feet.” (Daniel Deffenbaugh) God can be found in the ordinary events of our day-to-day lives, if we find ways to pay attention. In her book, No Moment Too Small, Norvene Vest writes about Benedictine spirituality which supports this perspective on the world: Benedict perceives God as present immediately and actively within the ordinary materials and interactions of each day. Every encounter, every incident during the day is grist for the mill of the ongoing God-human communication. No activity is too small or too unimportant to mediate the holy. Living one's faith in this way results in a much deepened attentiveness to each moment, for we learn that the specific ordinariness of a thing or a person also reveals a more "dense" reality, that is, its glory. Benedict's Rule always celebrates the simple daily actions of one person with another, and of human hand with pot and pan, all as potentially carrying a wonderful message (p. 19) So, where in our ordinary dust beneath our feet world, may we find and experience holy ground? “Maybe it’s when we are taking a walk and an idea comes to us about some change we need to make in our life. Or maybe we are in the midst of an argument with a family member and we remember that we love this person. That realization can cause the ground to shift, and suddenly there is a new opportunity in the midst of that relationship. Or maybe we are busy with just about everything, and a child asks us to read a story to them.” (Homiletics, 8/11) Maybe we are camping and we look up at that big wide sky, and are once again overwhelmed with the created order. One of the privileges pastors have, is to share the big moments of people’s lives. For me, the most incredible is to be present within hours of a child’s birth. Talk about holy ground. In her book For the Time Being, Annie Dillard writes that "there is no less holiness at this time as you are reading this - than there was the day the Red Sea parted .... There is no whit less enlightenment under the tree by your street than there was under the Buddha's bo tree. There is no whit less might in heaven or on earth than there was the day Jesus said, "Maid, arise" to the centurion's daughter, or the day Peter walked on water, or the night Mohammed flew to heaven on a horse. In any instant the sacred may wipe you with its finger. In any instant the bush may flare, your feet may rise, or you may see a bunch of souls in a tree. In any instant you may avail yourself of the power to love your enemies; to accept failure, slander, or the grief of loss." Earlier this summer, I had the opportunity to sing the national anthem at a Brewer’s game, with the choir I’m a part of. When they led us onto the field, we were lined up right behind home plate, standing on the Brewer’s logo—and as I looked down to see that logo, there was something of holy ground—just because of the famous people who’ve played there, and that it’s a special place for so many. But that’s not really what I’m talking about, in terms of holy ground. I would say a holy ground experience might be those times when something of God’s identity is revealed to us and we noticed—we learned more about God. Or we become aware of our relationship to God and our place in the universe—we noticed—and we learned about ourselves. Perhaps part of what it takes, is to take notice—to be aware. We’re not alone—it took a burning bush to get Moses’ attention. Elizabeth Barrett Browning acknowledges that much of the time we don’t notice. Earth’s crammed with heaven, And every common bush afire with God; And only the one who sees takes off their shoes; The rest sit round it and pluck blackberries. “There is a lot more holy ground around than we are normally conscious of. Perhaps it would be good for us to include in our daily prayers that God help us be more aware, as God did for Moses, of when we are walking on those places, so that we too can take off our shoes to fully experience the blessedness of the moment and discover what God wants to make of it and of us.” (Homiletics, 8/11) --Sue Burwell