MODULE 3 - Cancer Learning

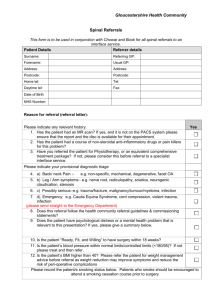

advertisement

MODULE 4 MANAGING COMMON HEALTH CONCERNS Introduction Hi and welcome to Module 4: Managing Common Health Concerns. When you’re ready to begin, click the next button. In this module This module covers 6 main topics, they are: Impact of Cancer and its Treatment- this is about common physical and psycho social effects of cancer and its treatment; Assessing and Managing Supportive Care Needs- this is about stratification and supportive care; Screening for Need and Information Provision- this covers who to screen and what to include when screening; Further Referral for Assessment and Intervention- this is about tools used to assist knowing when to provide further referral; Early Intervention Tailored to Need- this covers specific examples of health professional interventions for survivors; and Referral for Specialised Services and Programs- this covers when to refer and who to refer to. Impact of cancer and its treatment Whilst many cancer survivors experience high quality of life, many still experience physical and/or psycho social effects of cancer and its treatment. Some sequelae become evident during treatment, called Long Term Effects, while others may not manifest for months or years following active therapy, and these are called Late Effects. These effects can range in severity and impact, from mild to severe, and extent of associated disability. Some effects can also be potentially life threatening. It has been reported that at least 50% of survivors experience some Late Effects of cancer treatment. The most common problems in cancer survivors are depression, pain and fatigue. Physical effects in cancer survivors include pain, musculoskeletal issues, organ toxicities, fatigue, lack of stamina, urinary or bowel problems, lymphedema, premature menopause, cognitive deficits and sexual dysfunction. Physical changes is an ACSC information page covering these issues. There are 3 main categories for effects of cancer and its treatment, they are: Pulmonary Effects, Cognitive Effects and Cardiac Effects. Pulmonary Effects include bleomycin induced pneumonitis, which is a dosedependent, reversible acute toxicity that may progress in pulmonary fibrosis. Radiation pneumonitis is reported in 5-15% of lung cancer patients receiving definitive external beam radiation therapy. A minority of individuals may develop progressive pulmonary fibrosis. Late pulmonary complications specific to haematopoietic stem cell transplantation patients who develop interstitial pneumonitis, include idiopathic pneumonia syndrome and bronchiolitis obliterans. Studies have reported than 17-75% of women experienced cognitive deficit 6 months to 20 years after exposure to chemotherapy to breast cancer. Whole brain radiation is associated with delayed cognitive changes. It is difficult to determine the cause of cognitive issues in the cancer survivor. Aging, depression, stress, cancer treatments, or a combination of these factors have been associated. Cardiac effects may manifest years after cancer treatment is completed. The estimated aggregate incidence in radiation induced cardiac disease is 10-30% in 5 to 10 years, although this may be improving with new techniques. Broad categories of effects have been described, and these are: vascular disease, hypertension, thrombosis and myocardial dysfunction. You can click each of these buttons to see some more details about them. Impact of cancer and it’s treatment continued Cancer survivors are at increased risk of subsequent malignant neoplasms, or second cancers, due to genetic susceptibilities (for example, cancer syndromes), shared etiological exposures (for example, smoking and environmental exposures), and mutagenic effects of cancer treatment. Incidence of subsequent unrelated cancers ranges from 2% in survivors of malignant lymphoma, to 30% in survivors of small cell lung cancer. A range of psycho social effects are experienced by survivors. Cancer can have positive effects for some individuals, including strengthened relationships, a sense of gratitude or empowerment, or an increased appreciation for life. Psychological distress experienced by survivors, is linked to concerns about fear of recurrence or death, or to ongoing physical, social or practical problems associated with the cancer diagnosis and its treatment. As many as 19% of survivors meet the criteria for Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. There are 2 links provided which are ACSC information pages- 1 on Emotional Changes and 1 on Fear of Cancer Coming Back. Practical and social problems of survivors include those issues surrounding employment, finances and health and life insurance. There’s an ASCS information page on finance, work and insurance also. There are evidence summaries available for sexual dysfunction, fatigue, distress and adult cancer pain. Assessing and managing supportive care needs Supportive Care screening, assessment and referral of cancer survivors in Australia is an emerging area of practice. Tools specifically adapted to meet the needs of cancer survivors are in development. The model presented is an example of best practice Supportive Care. The practices of health services should reflect evidence based practice, but be customised according to the resources and expertise available within the multidisciplinary team, pathways for referral and access to services. Screening for need and information provision All survivors should be routinely and periodically screened for Supportive Care needs using a systematic, evidence based approach. Screening involves the routine and systematic identification of potential Supportive Care needs or risk factors, before the issue becomes a symptom. Key steps in screening include: the person affected by cancer completes the screening tool; following the completion of the tool, a discussion is held between the person and the health clinician to identify the health priorities, evaluate their impact on daily living and quality of life; and plan for further assessment and referral as needed. Documentation is also a key step. Examples of validated screening tools include: the distress thermometer and problem checklist, the Peter Mac Supportive Needs Screening Tool and the Needs Assessment Tool for Carers. Screening activity Describe the processes used for screening cancer survivors Supportive Care needs in your health setting. Consider how effective these processes are in identifying needs. Access the Supportive Cancer Care Victoria Supportive Care Screening Tools Summary Guide to review the evidence underpinning validated tools, such as the distress thermometer and problem checklist, the Peter Mac Suupportive Needs Screening Tool and the Needs Assessment Tool for Carers. Also in your response, consider if the screening processes in your health setting are evidence based. A Supportive Care Needs Screening Process Guide describes suggested methods for undertaking Supportive Care screening. You can click the buttons for more information about each of these. Further referral If Supportive Care needs are identified as part of a screening process, a more focused assessment of those needs or the sources of distress may be appropriate. Through discussion of Supportive Care concerns, clinicians can work collaboratively with cancer survivors to identify their existing resources and capabilities for self-management, and identify a need for additional supportive services. Person centred communication skills facilitate the process of assessment and effective interviewing. A range of tools can be used to guide this more focused assessment. Some examples are provided on screen, including: tools to assess specific symptoms or concerns (such as the Brief Pain Inventory, spirituality assessment and Bristol stool chart), tools to diagnose specific mental health concerns (such as the hospital and anxiety depression scale), promise measures. Grading scales for physical symptoms are identified in the common terminology criteria for adverse offence. And these provide a framework for a consistent assessment of need. The focused assessment may indicate the need for further support and survivors may be referred to other members of the multidisciplinary team. Specialist cancer nurses with advanced skills in communication and available support processes, such as clinical supervision, may be able to provide this level of intervention. Fewer than 10% of people are actually referred to psycho social help, despite having needs identified. Reasons for the lack of follow up include inappropriate timing of referrals, clinicians not knowing the Supportive Care resources available, clinicians not asking about Supportive Care needs, and clinicians not able to skillfully introduce the Supportive Care service. Further referral activity 1 Identify a Supportive Care need common to survivors in your health service. Outline the process to undertake a focused assessment of this need to identify the etiology and intervention strategies. In your response, consider the recommendations outlined by Supportive Cancer Care Victoria, in the post screening discussion tool and the referral pathway classification guide. Further referral activity 2 Identify the process for referral in your health setting, if a focused assessment indicates the need for further support from a member of the MDT. Reflect on the barriers and enablers you experience in referring cancer survivors. In your response, consider these guidelines and tools developed by Supportive Cancer Care Victoria. After you’ve finished your answer, click the buttons to see some examples of recommendations to improve the process of referral, and communication skills to encourage acceptance of a referral. Early intervention tailored to need Some cancer survivors will require cancer supportive care interventions, which require the services of specialist cancer professionals. A combination of activities, rather than any single intervention by itself, is also likely to be the approach required. Supporting people to manage their illness may involve education, development of new skills, preparing for a threatening procedure or a brief counseling intervention. Central to all these components is coordination of care, therapeutic communication and evaluation of the effectiveness of care. There are 2 examples of this level of health professional intervention. You can click each of the buttons to learn more about them. Referral to specialty Referrals to other health professionals or services are sometimes required to provide specialised support or address more complex issues beyond the capabilities of the multidisciplinary team. Referral may be indicated to meet a need for specialist information or to help manage specifically identified risk factors or needs such as persistent physical symptoms, people socially or financially at risk, people with culturally and linguistically diverse or with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander backgrounds, perceptions of hopelessness and pre morbid mental health issues. Examples of specialised services and programs include a lymphedema practitioner, continence physiotherapists, sex therapists and psychiatrists. Clinicians may consider referrals to the person’s General Practitioner to access services covered by Medicare through the GP Mental Health Plan or Chronic and Complex Care Plan. Two links are provided. One to the Chronic Disease Management Medicare Items and one to the Allied Health Services Under Medicare Fact Sheet. On screen is the Cancer Council Victoria’s specialist referral advertisement. Referral to specialty activity Identify a Supportive Care need experienced by cancer survivors in your health service, which requires specialist referral. Identify local health professionals or services to meet survivors’ needs and outline the local referral process to the health professional and/or service. References 1 These 2 slides contain the list of references used to create this module. Thanks for listening.