PS 831: Roman Political Thought (Spring 2014)

advertisement

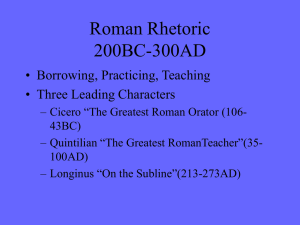

PS 831: Roman Political Thought Spring 2013 Monday, 3:30-5:30 Daniel Kapust Associate Professor Department of Political Science 311 North Hall djkapust@wisc.edu Office Hours: Monday, 9:30-11:30 or by appointment I. Scope and Purpose Why devote a seminar to Roman political thought? On the face of it, such a focus might seem odd; after all, 20th century political theory and philosophy generally focused on Greek political thinkers – we may think of Arendt, Strauss, or MacIntyre, to name but a few. Indeed, Dean Hammer suggests that he wrote his own recent book on Roman political thought in response to a question he was asked: “What ever happened to the Romans?” Not only have the Romans been strikingly absent from 20th century political theory and philosophy, Roman political thinkers – such as Cicero or Seneca – are often viewed as derivative of their Greek predecessors, be they Hellenic or Hellenistic. This was not always the case: Roman thought was of great importance through the 18th century, evident in figures such as Augustine, Aquinas, Machiavelli, Hobbes, Rousseau, and Madison. And focusing on Roman political thought seems less strange when viewed through other disciplinary lenses: scholars in English, history, the Romance languages, theater, and other fields did not lose interest in the Romans in the same way that political theorists and philosophers did. Yet Roman political thought has been undergoing something of a revival in recent years, due in part to increased interest in republicanism among political theorists and philosophers (evident in the work of figures such as Quentin Skinner and Philip Pettit), and also due to increased interest in rhetoric and the rhetorical tradition. Beyond republicanism and rhetoric, the Romans would seem to be increasingly relevant to our own politics: after all, Rome was an imperial republic faced with apparent trade-offs between liberty and security. Increasingly, then, work on Roman writers focuses on them less as sources for – or in conversation with – later writers, and more as rich resources for political theorizing. We will take the writers we encounter as figures worth studying in their own right, though we will, of course, pay attention to issues of reception and influence. The majority of the writers we encounter will be Romans writing in Latin: the exceptions are Polybius, a Greek who spent time in Rome and wrote for a Greek audience, and Plutarch, a Greek living under Roman rule. We will read texts that fit in the (somewhat narrow) confines of traditional philosophical genres – Cicero’s dialogues, and Seneca’s essays. But we will also read texts from genres that are not philosophical in a narrow sense: works of history, poetry, oratory, and philosophical confession. In the course of studying these texts, participants in the seminar will gain a deep understanding of the Roman ethical, social, and political tradition from the 2nd century B.C.E. to the 5th century C.E. Students will write and present seminar papers engaging with political theory, philosophy, and classical scholarship that are suitable for development into conference papers and ultimately articles or dissertation chapters. II. Course Requirements Students enrolled in the course for credit will write a staged seminar paper. The paper, memos, and the in-class presentations on May 2 and 9, will be worth 75% of the course grade.The goal is to produce a paper that can be presented at a conference and eventually be suitable for publication. You will, in short, be preparing your own contribution to scholarship on Roman political, social, or ethical thought. The paper will be broken up into 5 stages: 1. Meeting with me to discuss the topic and a preliminary bibliography. To be completed no later than Monday, February 17. 2. A 10-12 page annotated bibliography, to be turned in to me or placed in my departmental mailbox by Friday, March 14. 3. A detailed outline of the paper (3-5 pages), to be turned in to me or placed in my departmental mailbox on or before Friday, April 4. 4. The final seminar paper (25-35 pages), to be turned in to me or placed in my departmental mailbox no later than Friday, March 25. 5. Two short memos (i.e. between 250 and 500 words), to be turned in to me or placed in my mailbox by Monday, 5/8). A. The first memo is to be in response to my comments on your paper. You should, in this memo, outline what you take the core of my concerns to be, and how you would go about addressing them. This memo is, in essence, analogous to the memos you will be writing in response to referee reports when you send papers out for review. B. The second memo is to be in response to comments made on your presentation. You should, in this memo, try to synthesize these comments, and outline how you would go about addressing them. This memo is, in essence, analogous to what many try to do after presenting papers at conferences. You will receive a grade for the paper as a whole, and not for the individual components, each of which is designed to help you produce a stronger paper. In order to receive credit for the paper, however, you need to complete each of the components. The last two days of the course will be reserved for presentations of seminar papers. You should view this as, in essence, a practice conference presentation, and will be allotted 15 minutes to present your paper. We will then have 10-15 minutes of class discussion of the papers. The goal of this exercise is to familiarize you with the basics of presenting at conferences, to provide further feedback on your papers, and to further enrich the mutual learning experience of the seminar by incorporating peer feedback. The paper itself should be viewed as a future conference paper, and eventual publication. In addition to the seminar paper and presentation, participation will be worth 25% of the course grade. This involves closely and carefully reading the assigned material, and participating in seminar discussion. It also requires each participant to lead discussion once during the semester. Auditors will be expected to do all the readings and to lead one discussion during the semester. III. Incompletes and Academic Dishonesty Incompletes for this course will only be granted under extraordinary circumstances. Academic dishonesty will not be tolerated, and will be subject to severe penalties. IV. Texts I have ordered 11 books for this course, each of which is required. 1. Cicero, On the Ideal Orator, translated by James M. May and Jakob Wisse (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001) 2. Cicero, The Republic and The Laws, translated by Niall Rudd (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998) 3. Cicero, On Duties, translated by M.T. Griffin and E.M. Atkins (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991) 4. Seneca, Moral and Political Essays, edited by John M. cooper and J.F. Procope (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995) 5. Sallust, Catiline’s Conspiracy, The Jugurthine War, Histories, translated by William Batstone (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010) 6. Livy, The History of Rome Books I-V, translated by Valerie Warrior (Indianapolis: Hackett, 2006) 7. Tacitus, Agricola, Germany, Dialogue on Orators, translated by Herbert Benario (Indianapolis: Hackett, 2006) 8. Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, translated by G.M.A. Grube (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1983) 9. Lucretius, On the Nature of Things, translated by Martin Ferguson Smith (Indianapolis: Hackett, 2001) 10. Augustine, Political Writings, translated by Michael W. Tkacz and Douglas Kries (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1994) 11. Plutarch, Moralia, Vol. X, translated by Harold North Flower (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1936) V. Recommended Reading Listed below is a small number of monographs, essays, and edited volumes that are particularly useful for general reading on Roman political thought; a selection of more specific sources will be provided with each week’s readings. This list is very much incomplete, and reflective of my own scholarly predilections (as are the works I note for the specific readings). The general list is also very heavily weighted toward the late Republic and early Principate. Arena, V. Libertas and the Practice of Politics (Cambridge, 2012) Balot, R., ed., A Companion to Greek and Roman Political Thought (Malden, 2009) Baraz, J., A Written Republic (Princeton, 2012) Brunt, P.A. “Libertas in the Republic,” in The Fall of the Roman Republic and Other Related Essays (Oxford, 1988) (THE WHOLE VOLUME IS OF GREAT USE) Connolly, J. The State of Speech (Princeton, 2007) Eckstein, A. Mediterranean Anarchy, Interstate War, and the Rise of Rome (Berkeley, 2006) Edwards, C. The Politics of Immorality in Ancient Rome (Cambridge, 1993) Galinsky, K. Augustan Culture (Princeton, 1998) Garnsey, P. and R. Saller The Early Principate: Augustus to Trajan (Oxford, 1982) Griffin, M. “Philosophy, Politics, and Politicians at Rome,” in Philosophia Togata (Oxford, 1989) (THE WHOLE VOLUME IS WORTH ATTENTION) Hammer, D. Roman Political Thought and the Modern Theoretical Imagination (Oklahoma City, 2008) Harris, W.V. War and Imperialism in Republican Rome (Oxford, 1979) Kapust, D. Republicanism, Rhetoric, and Roman Political Thought (Cambridge, 2011) Kaster, R. Emotion, Restraint, and Community in Ancient Rome (Oxford, 2005) Kraus, C. and Woodman, A.J., Latin Historians (Oxford, 1997) MacKendrick, P. and K.L. Singh, The Philosophical Books of Cicero (Duckworth, 1989) Millar, F. The Crowd in Rome in the Late Republic (Michigan, 1998) Morford, M The Roman Philosophers (Routledge, 2002) Morstein-Marx, R. Mass Oratory and Political Power in the Late Roman Republic (Cambridge, 2004) Murphy, C. Are we Rome? (Houghton Mifflin, 2007) Nederman, C.J. “Rhetoric, Reason, and Republic: Republicanisms – Ancient, Medieval, and Modern,” in Hankins, ed., Renaissance Civic Humanism (Cambridge, 2000) Nicolet, C. The World of the Citizen in Republican Rome (Berkeley, 1980) Nussbaum, M. The Therapy of Desire: Theory and Practice in Hellenistic Ethics (Princeton, 1994) Powell, J.G.F., ed. Cicero the Philosopher (Oxford, 1995) Raaflaub, K. “Aristocracy and Freedom of Speech in the Greco-Roman World,” in Sluiter and Rosen, eds., Free Speech in Classical Antiquity (Leiden, 2004) Roller, Constructing Autocracy (Princeton, 2001) Rowe, C. and M. Schofield, eds. The Cambridge History of Greek and Roman Political Thought (Cambridge, 2005) Sullivan, J.P Literature and Politics in the Age of Nero (Ithaca, 1985) Syme, R. The Roman Revolution (Oxford, 1939) Wallace-Hadrill, A. “Mutatio morum: The Idea of a Cultural Revolution,” in Habinek and Schiesaro, eds, The Roman Cultural Revolution (Cambridge, 1998) Wirszubski, C. Libertas as a Political Idea at Rome (Cambridge, 1950) Wiseman, T.P. Remembering the Roman People (Oxford, 2009) VI. Schedule of Readings and Seminars 1/27: Setting the Stage Reading: Polybius, Histories Book VI (To be available via Learn@UW) Hammer, Roman Political Thought and the Modern Theoretical Imagination, Chapter 1 Kapust, Republicanism, Rhetoric, and Roman Political Thought, Chapter 1 Recommended: Murphy, Are We Rome? Walbank, Polybius Eckstein, Moral Vision in the Histories of Polybius Baronowski, D., Polybius and Roman Imperialism 2/3: The Rhetorical Republic Reading: Cicero, On the Ideal Orator (selections TBA) Recommended: May, ed., Brills Companion to Cicero: Oratory and Rhetoric Steele, Roman Oratory Fantham, The Roman World of Cicero’s De Oratore Remer, “The Classical Orator as Political Representative,” Journal of Politics 72.4 (2010) Alexander, “Oratory, Rhetoric, and Politics in the Republic,” in Dominik and Hall eds., Companion to Roman Rhetoric Goodwin, J. “Cicero’s Authority,” Philosophy and Rhetoric (2001) Stem, R. “Cicero as Orator and Philosopher: The Value of the Pro Murena for Ciceronian Political Thought,” Review of Politics (2006) Remer, G. “Political Oratory and Conversation: Cicero versus Deliberative Democracy,” Political Theory (1999) Garsten, B., Saving Persuasion (Cicero chapter specifically) 2/10: The Republic in and through History Reading: Cicero, On the Republic, On the Laws Recommended: Powell, ed., Cicero the Philosopher Nicgorski, ed., Cicero’s Practical Philosophy Wood, Cicero’s Social and Political Thought Schofield, “Cicero’s Definition of Res publica,” in Schofield, Saving the City Cornell, “Rome: The History of an Anachronism,” in Mohlo, Raaflaub, and Emlen, eds., City States in Classical Antiquity and Medieval Italy Powell, J.G.F. and J.A. North, eds., Cicero’s Republic Fantham, E. “Aequabilitas in Cicero’s Political Theory, and the Greek Tradition of Proportional Justice,” Classical Philology (1973) Asmis, E. “A New Kind of Model: Cicero's Roman Constitution in De Republica,” American Journal of Philology (2005) Atkins, J., Cicero on Politics and the Limits of Reason 2/17: Re-founding the Republic Reading: Cicero, On Duties Recommended: Long, “Cicero’s Politics in De Officiis,” in Laks and Schofield, eds., Justice and Generosity Gill, “Panaetius on the Virtue of Being Yourself,” in Bulloch, Gruen, Long, and Stewart, eds., Images and Ideologies Gill, C. “Personhood and Personality: The Four-Personae Theory in Cicero, De Officiis,” Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy (1988) Nicgorski, W. “Cicero’s Paradoxes and his Idea of Utility,” Political Theory (1984) Kapust, D. “Cicero on Decorum and the Morality of Rhetoric,” European Journal of Political Theory (2011) 2/24: The Republic: Crisis Reading: Sallust, War with Catiline Sallust, War with Jugurtha Recommended: Wallace-Hadrill, A. “Mutatio morum: the idea of a cultural revolution,” in Habinek and Schiesaro, eds., The Roman Cultural Revolution Fontana, B. “Sallust and the Politics of Machiavelli,” History of Political Thought (2003) Levene, D. “Sallust’s Catiline and Cato the Censor,” The Classical Quarterly (2000) Boyd, B.W. “Virtus Effeminata and Sallust’s Sempronia,” Transactions of the American Philological Association (1987) Stewart, D. “Sallust and Fortuna,” History and Theory (1968) Syme, R., Sallust Wiedemann, T. “Sallust’s ‘Jugurtha’: Concord, Discord, and the Digressions,” Greece and Rome (1993) Batstone, W.V. “The Antithesis of Virtue: Sallust’s Synkrisis and the Crisis of the Late Republic,” Classical Antiquity (1988) Konstan, D. “Clemency as a Virtue,” Classical Philology (2005) Yavetz, Z. “The Res Gestae and Augustus’ Public Image,” in Millar and Segal, eds., Caesar Augustus: Seven Aspects Feldherr, A. Spectacle and Society in Livy’s History 3/3: The Republic: Alternatives Reading: Lucretius, On the Nature of Things (selections) Recommended: Clay, D., Lucretius and Epicurus Gale, M., ed., Oxford Readings in Classical Studies: Lucretius Gillespie, S., and P. Hardie, eds., The Cambridge Companion to Lucretius Asmis, E., “Rhetoric an Reason in Lucretius,” American Journal of Philology (1983) Jones, H., The Epicurean Tradition Lehoux, D., Morrison, A.D., and A. Sharrock, eds., Lucretius: Poetry, Philosophy, Science 3/10: Augustan Rome: Defects and Remedies Reading: Livy, From the Founding of Rome, Books I through V Recommended: Vergil, Aeneid, Book VI Vergil, Eclogue IV Brown, “Livy’s Sabine Women and the Ideal of Concordia,” Transactions of the American Philological Association 125 (1995) Chaplin, Livy’s Exemplary History Konstan, D., “Narrative and Ideology in Livy: Book I,” Classical Antiquity (1986) Ogilvie, R.M. A Commentary on Livy Books 1-5 Syme, R. “Livy and Augustus,” Harvard Studies in Classical Philology (1959) Walsh, P.G., Livy Luce, T.J., Livy: The Composition of his History 3/24: Stoicism and the Early Principate Reading: Seneca, On Anger, On Mercy, On the Private Life Recommended: Bartsch, S., 2009, “Senecan metaphor and Stoic self-instruction,” in eds. S. Bartsch and D. Wray, Seneca and the Self, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 188–217. (THE WHOLE VOLUME IS WORTH ATTENTION) Griffin, M., 1992, Seneca: A Philosopher in Politics 2nd edn., Oxford: Oxford University Press Inwood, B. 2005, Reading Seneca: Stoic Philosophy at Rome, Oxford: Oxford University Press Long, A. A., 2003, “2006, “Seneca on the self: why now?,” in A. A. Long, From Epicurus to Epictetus: Studies in Hellenistic and Roman Philosophy, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 360–376. 3/31: Rethinking Public Life Reading: Tacitus, Dialogue on Orators, Agricola, Germania Pliny, Panegyric to Trajan (To be available via Learn@UW) Recommended: Ahl, “The Art of Safe Criticism in Greece and Rome,” The American Journal of Philology (1984) Connolly, J., “Fear and Freedom: A New Interpretation of Pliny’s Panegyricus,” Ordine e sovversione nel mondo grece e roman, ed. Gianpaolo Urso Bartsch, S. Actors in the Audience: Theatricality and Doublespeak from Nero to Hadrian Boesche, R. “The Politics of Pretence: Tacitus and the Political Theory of Despotism,” History of Political Thought (1987) Roche, P., ed., Pliny’s Praise Pagan, V., ed., Companion to Tacitus (KAPUST ON TACITUS AND POLITICAL THEORY, AMONG OTHER CHAPTERS) Syme, R., Tacitus (2 volumes) Saxonhouse, A. “Tacitus’s Dialogue on Oratory: Political Activity under a Tyrant,” Political Theory (1975) Goldberg, S., “Appreciating Aper: The Defense of Modernity in Tacitus’ Dialogus de Oratoribus,” Classical Quarterly (1999) Riggsby, A. “Pliny on Cicero and Oratory: Self-Fashioning in the Public Eye,” The American Journal of Philology (1995) Fantham, E. “Imitation and Decline: Rhetorical Theory and Practice in the First Century after Christ,” Classical Philology (1978) 4/7: Plutarch Reading: Selected essays from Moralia Volume 10 Recommended: Aalders, G., Plutarch’s Political Thought Mossman, J., ed., Plutarch and his Intellectual World Gill, C., The Structured Self Lamberton, R., Plutarch 4/14: Marcus Aurelius Reading: Marcus Aurelius, Meditations Recommended: Asmis, E., 1989. ‘The Stoicism of Marcus Aurelius.’ Austieg und Niedergang der Römischen Welt II.36.3: 2228–2252. Brunt, P. A., 1974. ‘Marcus Aurelius in his Meditations.’ Journal of Roman Studies, 64(1): 1–20. Cooper, J. M., 2004. ‘Moral Theory and Moral Improvement: Marcus Aurelius’, in Cooper, Knowledge, Nature and the Good (Princeton), 335–368. Hadot, P., tr. M. Chase, 1998. The Inner Citadel: The Meditations of Marcus Aurelius. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Annas, J., The Morality of Happiness Rutherford, R.B., The Meditations of Marcus Aurelius: A Study 4/21: Augustine Reading: Augustine, Political Writings Recommended: NOTE: There is an extraordinary amount of scholarship on Augustine (who was both remarkably prolific and is remarkably influential); the following list is very much minimal, and geared towards collections. Brown, P., Augustine of Hippo: A Biography (1967, updated version in 2000) Deane, The Political and Social Ideas of St. Augustine Evans, G.R., Augustine on Evil Holt, Laura, “A Survey of Recent Work on Augustine,” Heythrop Journal: A Bimonthly Review of Philosophy and Theology (2008) Markus, R.A., ed., Augustine: A Collection of Critical Essays Matthews, G., ed., The Augustinian Tradition Stump, E. and N. Kretzman, eds., The Cambridge Companion to Augustine Wetzel, J. Augustine and the Limits of Virtue Pasnau, R., ed., The Cambridge History of Medieval Philosophy Armstrong, A.H., ed., The Cambridge History of Later Greek and Early Medieval Philosophy 4/28: Presentations (to be held on the Terrace or at Memorial Union) 5/5: Presentations (to be held on the Terrace or at Memorial Union)