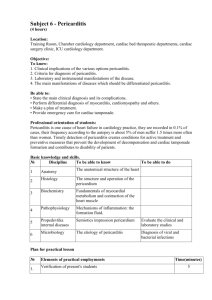

Causes of acute pericarditis

advertisement

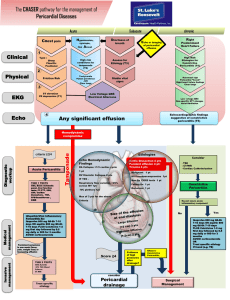

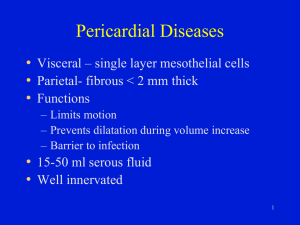

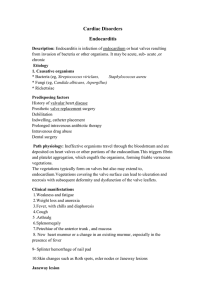

Pericarditis and Myocarditis High risk Causes Assessment T >38.5, subacute onset, immunosupp, recent trauma, anticoagulation, myopericarditis, large pericardial effusion Idiopathic: 25% Viral: enterovirus (coxsackie, echovirus), adenovirus, mumps, EBV, VZV, hep B, flu, HIV Bacterial: Staph aureus, pneumococci, beta-haemolytic strep, strep pneumonia, legionella, salmonella, psittacosis, military TB / direct pul spread Ca: 25%; occurs in 10% Ca patients; adults (lung, breast, lymphoma, leukaemia, melanoma); children (Hodgkins, lymphosarcoma, leukaemia); results in tamponade in 50-85% MI: transmural; within 1-5/7 Auto-immune: RA (most common autoimmune cause), SLE, Dressler’s syndrome (up to 6/52 post-MI, MOST COMMON CAUSE), sarcoidosis Drugs: hydralazine, procainamide Other: Serum sickness, trauma, irradiation, cardiac surgery (v common), severe uraemia (tamponade common) Sx: CP (relieved sitting forward; absent in 50% (esp if chronic / Ca); low grade fever; dysphagia; SOB; weakness; syncope OE: pericardial rub (high pitched, best with diaphragm over L sternal border; may be triphasic or biphasic; incr on inspiration / sitting forward / with heart beat; transient – may last only 30mins; decr as pericardial effusion increases); pericardial effusion Ix ECG: abnormal in 90%; may be normal if uraemic / RA; Changes usually diffuse but may be localized; DD = early repolarization (usually only V1-3), MI (usually regional); widespread Q waves not seen in pericarditis Phase 1 – hrs to days: widespread non-regional concave STE in I, II, V5-6 (not in aVR, V1, II, III, aVF) Present in initial ECG in 66%; in 95% with incr trop; in 60% without incr trop PR depression in 80% (most common in II; can occur in all leads except aVR, V1) ST depression and PR elevation in aVR and V1 No distinct J point; slightly short QTc Knuckle sign in PR segment of aVR Phase 2 – days: ST segments normalize PR depression in 60% Small T waves Phase 3 – days to wks: TWI in leads that prev had STE Low voltages; sinus tachy Phase 4 – 1-3 months: Normalisation; some T wave changes may be permanent Mng CXR: pneumonia / pleural effusions if bacterial; underlying cause Straightening of L heart border; globular heart (if >200ml effusion and slow onset); pericardial calcification in 50% chronic; pericardial fat lines on lateral (high spec for pericardial effusion) Echo: pericardial effusion in 40%; pericardial thickening; localized wall motion abnormalties in 7% Trop I: incr in 50% at presentation; incr in most with WMA; myocarditis in significantly incr Other bloods: FBC; ESR and CRP (used to track trt) Pericardial aspiration: MC+S, AFB staining, ANF, RF Supportive; NSAIDs (not aspirin); relieve tamponade if needed Bacterial: broad spectrum ABx, pericardial aspiration, HDU/ICU Myocarditis Uraeamic: dialysis Autoimmune: immunosupp Dressler’s: steroids More common in children and young adults; common cause of sudden death in previously well Causes: viral and autoimmune as above, bacterial (Q fever, N meningitidis, M pneumoniae, C diptheriae, chlamydia, C burnetti, beta haem strep), parasitic (Chagas disease most common cause worldwide, toxoplasma), drugs (doxorubicin, ETOH, cloazpine, radiation) Sx: non-specific; weakness, SOB, CP, fever, dizziness, palpitations, recent flu-like illness OE: incr HR out of proportion to fever, incr RR, hepatomegaly, fever, creps, normal/high BP but poor perfusion, maybe rapid deterioration, LVF uncommon Ix: incr HR, low ECG voltages in 80%, ST/T changes, conduction disturbances, long QTc, may be normal early; cardiomegaly, pleural effusions; global decr contractility on echo, decr EF, V dilation; incr cardiac markers; incr ESR in autoimmune; myocardial biopsy (50-70% sens) Mng: supportive; CCF trt; bed rest; inotropes, diuretics, vasoD, ACEi, trt arrhythmia; mechanical support if hypoperfusion despite meds (ECMO, V assist devices); steroids / immunosupp if autoimmune Prognosis: most deaths in 3-4/7; >95% survivial if last >72hrs; often progresses to dilated CM; no competitive sport for 6/12 Causes of acute pericarditis: In western countries most cases of acute pericarditis in immunocompetent patients are due to viral infection or are idiopathic. Typically the illness follows a brief and benign course after empiric treatment with anti-inflammatory drugs. Other causes need to be considered in high risk patients. These include tuberculosis, bacterial infections, neoplasms, uremia, connective tissue / autoimmune disorders, drugs, trauma and myocardial infarction. Haemorrhagic pericarditis involves blood mixed with a fibrinous or supperative effusion, and is most commonly caused by tuberculosis or direct neoplastic invasion. This condition can also occur in severe bacterial infections or in patients with bleeding diathesis. It is common after cardiac surgery. Serous pericarditis is characteristically produced by non-infectious inflammatory diseases such as rheumatic fever, SLE, scleroderma, tumours, and uremia. Uremic pericarditis has a prevalence of 6-10% of patients with acute or chronic renal failure with cardiac ultrasonography revealing a pericardial effusion in at least 50% of cases. Caseous pericarditis is a rare type of pericarditis that is tuberculous in origin until proven otherwise. Infrequently fungal infections evoke a similar reaction. Fibrinous pericarditis occurs in inflammatory pericarditis with fibrinogen leaking out of blood vessels and being converted to fibrin which forms a fibrinous exudate. Fibrinous and serofibrinous are the 2 most frequent types of pericarditis. Common causes include post MI, uremia, chest radiation, rheumatic fever, SLE, and trauma. A fibrinous reaction also follows routine cardiac surgery. Purulent or Suppurative pericarditis: Caused by invasion of the pericardial space by microbes resulting in an exudate that ranges from a thin cloudy fluid to frank pus up to 400 to 500 mL in volume. Complete resolution is infrequent, and organization by scarring is the usual outcome. The intense inflammatory response and the subsequent scarring frequently produce constrictive pericarditis Constrictive pericarditis; is the result of scarring and consequent loss of the normal elasticity of the pericardial sac resulting in impaired normal diastolic filling. The top 3 causes of constrictive pericarditis in descending order are idiopathic (presumably viral), cardiothoracic surgery and radiotherapy. All the other causes of pericarditis can also result in restrictive pericarditis. Tuberculous and bacterial pericarditis, while rare, are closely associated with constrictive pericarditis. The incidence of constrictive pericarditis post acute idiopathic/viral was 0.76 cases per 1000 person-years, but 31.7 cases for 1000 person-years for acute tuberculous pericarditis and 52.7 cases per 1000 person-years for purulent pericarditis. Causes of acute pericarditis: In western countries most cases of acute pericarditis in immunocompetent patients are due to viral infection or are idiopathic. Typically the illness follows a brief and benign course after empiric treatment with anti-inflammatory drugs. Other causes need to be considered in high risk patients. These include tuberculosis, bacterial infections, neoplasms, uremia, connective tissue / autoimmune disorders, drugs, trauma and myocardial infarction Myocardial infarction: Pericardial disease, manifested as pericarditis and/or effusion, is a common event following acute myocardial infarction. Both types of pericardial disease are related to infarct size and are less common in the era of revascularization. Acute pericarditis post MI occurred in 6.7% of patients receiving thrombolysis in the GISSI-1 and GISSI-2 trials. Later immunologically mediated pericarditis known as Dressler’s syndrome has become uncommon following the advent of reperfusion treatments. Trauma causing pericarditis may be blunt or sharp and may be iatrogenic in origin including all cardiac invasive diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, and rarely following cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Drugs and toxins: There is a long list of drugs that may cause pericardial disease. Procainamide, hydralazine, isoniazid and phenytoin can induce a lupus like syndrome. Penicillins may cause a hypersensitivity pericarditis with eosinophillia. Doxorubicin and danorubicin are more often associated with cardiomyopathy, but may cause pericardiopathy, as may other chemotherapy agents. Bacterial: While any bacterial infection may involve the pericardium, the most notable include staphylococcus, pneumococcus, streptococcus (rheumatic pancarditis), haemophilus, and M. tuberculosis. Systemic lupus erythematous (SLE) and rheumatoid arthritis are the most common rhematic diseases to involve the pericardium. In SLE the pericardium is involved in almost one half of patients. Pericardial effusion, when present, is usually clinically silent.