Women in the World War I Era and the Russian Revolution

advertisement

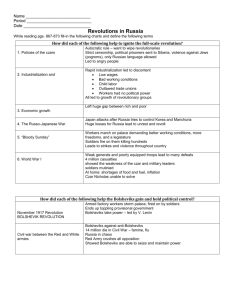

Women’s Roles in the World War I Era and the Russian Revolution World War I, 1914-1918, was probably the most important event of the twentieth century, for most likely there would not have been World War II, the Russian Revolution, the Great Depression, and the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the United States. All these wars and revolutions and their aftermath, had major influence on women's lives. The two world wars were a continuation in a long series of struggles beginning with Charles the V, the Holy Roman Empire in the sixteenth century, continuing with Napoleon and ending with Hitler to establish hegemony of one power over all of Europe. World War I was the "Great War" for Europeans; it was a great shocker like the Black Death in the fourteenth century. Approximately ten million men were shot, bayoneted, gassed or blown to pieces. Half of all the young men between the ages of twenty to thirty-two were killed. Russia suffered a quarter of a million casualties a month, and in the end 1,700,000 Russian men were dead. In all twenty million men in this war were seriously wounded; armless, legless, blinded, or broken in spirit. Five million widows were created, nine million children became orphans, and ten million became refugees. Even one million horses were killed or died. "Europe became an enormous cauldron into which men and resources from Asia, Africa, Europe, and America were poured." One noted historian of the period called the years preceding war as the "Road to Armageddon," and the war itself as Armageddon. Many were shocked even further when in 1920, two years after the war ended, a Colonel Repington entitled his account of the Great War, as The First World War. World War I changed forever Europe's domination of the world, and it wiped out the centuries-old dynasties and ruling houses of: Romanovs of Russia, Hapsburgs of Austria, the Ottomans and the German Empire. The new countries of Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Rumania, Yugoslavia were established, and Poland was resurrected. Eventually out the Middle East came the countries of Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Iran, and Palestine. At the beginning of the war most all of Europe believed war would set things right, and even make life beautiful. Our modern day society with a multitude of changes for women came out of this era. Why would Europe go to war? There are numerous long-term causes: Nationalism, militarism/jingoism, rival and secret alliance systems, armament races, imperialistic rivalries, and economic competition. When World War broke out in August 1914, it ended years of international disputes, where the West struggled against each other for colonies as sources of raw materials and markets for their industrial products. To strengthen their positions German and English governments had built huge fleets of warships/dreadnoughts, and invested heavily in military arms, conscripting millions of men. Incidents were continuously erupting in Asia, Africa and Eastern Europe. It was there in Serbia that in June of 1914, Serbian nationalists assassinated the heir to the Habsburg 2 Austrian/Hungarian Empire and his wife. Because of the Austro-Hungarian alliance with Germany, this particular event set Germany in motion to assist Austria. The Ottomans and Bulgaria also joined the Central Powers, all of whom were soon at war with Russia, France, Britain and later Italy. The United States came into the war when it had one year left. In the beginning of the war people thought it would be a short-lived war similar to the fairly recent Franco-Prussian war of 1871 when the Prussians under Otto von Bismarck forced France into war. Within six weeks the Prussians were in Paris, and the French capitulated. Now the first eight months of the World War I governments and the home front did not change all that much, but the French and Germans were bogged down in what became known as Trench Warfare. The British had joined the French. After this first phase, the second one lasted one and a half years, and now countries were turning their consumer manufacturing plants into war weapons, utilizing machine guns, artillery fire, poison gas, and eventually tanks. Women lost jobs not related to military efforts, and it is estimated that thirty to forty percent of European women lost their jobs. Even farms had to shut down for lack of male labor. Unemployment of women caused little initial stir as only women were out of work. Governments had made no plans to shift women to production for military needs. Older men substituted first in military factories in Germany, and it was not until 1915 that women starting working in heavy industry, allowing the men to fight. Only in 1916 did Germany give serious attention to the use of female labor. What appears new to women's experiences in the First World War was the relatively widespread feeling that women's traditional support for the armed forces was not enough. In this horrific struggle which demanded men risk their lives, it appeared women were not doing enough. Some of the privileged women insisted on active participation, but their families and men folk objected. Dr. Elsie Ingliss (1867-1917) offered to provide the British Army with fully staffed medical units. She was rejected by the War Office with the words: My good lady, go home and sit still." Not going home, Dr. Ingliss went to the allies of the British, who did accept her services. By 1917 she had organized and administered fourteen medical units for Belgian, French, Russian, and Serbian armies. Before the outbreak of World War I, the women's rights movements were in full flower. Women in general, though, gave up their pursuit of votes for women, and instead worked for victory for their country. Many women who were pacifists became militarists, and many socialists jettisoned the concept of international working-class solidarity to support their own country's war efforts. Thus many feminists and socialists suddenly were welcomed into the national endeavor. These women were given civic responsibilities for governments that needed women's loyalty to the war. Nations now recognized that they needed women's cooperation and efforts. An example of reactions by women was 3 the change in the famous British suffrage movement. Millicent Garrett Fawcett remarked in the English suffrage magazine, Common Cause, "Let us show ourselves worthy of citizenship." The famous mother and daughters of the Pankhurst family changed the name of their paper from The Suffragette to Britannia. They did extensive public relations in favor of the war. Travelling continually for four years, they spoke at bond-selling and recruitment rallies to raise the psychological support for the war. In France suffragists shows strong patriotism. In fact perhaps it was stronger in France than anywhere else, probably because most of the battles took place on French soil. The newspaper La Francaise spoke for most French feminists in November 1914 with these remarks: "While the ordeal our country is suffering continues, it will not be proper for anyone to speak of her rights." So they closed down their various newspapers or converted them to organs of wartime propaganda, and also used their experience as organizers to set up all kinds of groups aiding the war effort. Eventually women's participation changed as the war dragged on and millions of men became casualties of the trench warfare system after volunteering or being conscripted by the millions. Men's place on farms and in factories was taken by women. This varied in each country, including the percentage of women working in various areas. It was not just because men were not available, but wives of soldiers needed more money to support themselves and their families. This was true of single middle class women too. Patriotism and propaganda served to increase the number of women in the war effort. In most countries the propaganda for women's participation made it unpatriotic if they did not do war work. Great Britain had many posters and slogans urging women to do their part. Here are some of these: "Any woman who by working helps to release and equip a man for fighting does national war services; Shells made by a wife may save a husband's life." Other jobs that women engaged in were more dangerous. Nurses responded and were serving close to the front lines. Women drove ambulances like Marie Curie. Some women were spies, and some were executed by the enemy. Most women needed little urging, and for the first time they found themselves able to command higher wages than in the past. With more money coming in it brought more independence. Unfortunately one of the by-products of these increased opportunities for women led to negative charges against women regarding morality and working conditions. Detractors said that the weakening of morals and increased laxity regarding sex was true of the French, German and British women. We do know that a increased number of broken marriages occurred. Some people were convinced that this was due to women's new independence. Many others agreed with the statement of one French doctor that "war was leading to the masculinization of women." Fighting men felt that living it up for tomorrow they may die seems to have prevailed. 4 Fellow workers in the factories did not always welcome women workers either. French munitions workers made the common charge that hiring women in men's jobs enabled more and more men to be sent to the front to be slaughtered. Because of women, not because of war, men were becoming "cannon-fodder" as one poster showed. Proverbial accusations against women of centuries past surfaced again. If women were women in the workplace, this would lead to male unemployment and lower wages for men in the future. Women at the time expected the same wages as men for the same work, but both employers and the governments thought differently. Paying lower wages to women meant companies made more profits, and governments were able to buy more war materials. Many unions did support equal pay for women, but they were not always successful in obtaining it. Until 1914 when the war broke out, women's skirts were ankle-length, which they had been for over two thousands years. Skirts began to rise upwards as early as December 1914 (the war began in August). Within a year the skirts were ten inches off the ground. Women have never returned since to ankle-length day time wear. Naturally the press was full of remarks about the shocking aspect of female ankles and legs. Underclothes also changed. Where the ideal shape had been the hour glass figure achieved by a tight corset, and even worn eventually by working class women, now the loose chemise or brassiere materialized. After the war in the 1920's the brassiere itself was temporarily discarded in exchange for a flattening breast band, but this style only lasted about five years. Slimness rather than just tiny waists became the new "ideal." Fashionable women began to diet and watch their weight. Women modified their clothing to fit their new jobs. They now wore overalls. Women began to cut their hair. Before this most women had never cut their hair as it was their crowning glory. Now not only was it cut, but in a short bob fashion. Long hair came close to being considered unpatriotic as women working in factories and nurses were not allowed to wear long hair. During the war women began to use cosmetics, which until this time was a woman's signal that she was sexually available and also associated with prostitutes. By the mid twenties, it was standard practice for women to use: bright red lipstick, powder, rouge, mascara, eye shadow, and finger nail polish. Hollywood movies were highly influential in this new fashion. Now women were putting on their face before they were going out. Remarks in papers were not flattering. One English paper stated: "Women were coming to look like characters in a comic opera." Each country involved in the war used propaganda involving women to further their interests. Used were violence against women as a way to infuse hatred of the enemy, and keep people sacrificing for the war. French anti-German PR showed women violated sexually in front of their children. Rumanian newspapers reported that German women were the gouged-out eyes of wounded Frenchmen as necklaces. 5 Finally, the war came to an end, and on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month, the treaty was signed, whereby German was made to accept all the blame for the war, and to pay billions of dollars in reparations to the victors. German balked, for she said that she had beaten the Russians, when they surrendered in the third year of the war, and the Russian Revolution subsequently occurred. When the Ottoman Empire in the Middle East was dismantled, negotiations with the Muslims had already been going on, and Gertrude Bell had a significant role in the peace talks and settlement of mandates controlled by France and Britain in the Middle East. She was a famous woman in Europe, but not in America. T. H. Lawrence was well known thanks to Lowell Thomas, but Gertrude Bell's contributions were crucial. Bell and Lawrence of Arabia helped to create the Hashemite dynasty in Jordan and defined the outline of the modern state of Iraq. Educated in England, where she was born, within two years she had gained a first class honors degree in history. Her first visit to the Middle East was in Persia, where her uncle was living. She spent much of the next decade traveling around the world, and developing a passion for archaeology and languages. She became fluent in Arabic, Persian, French, German, Italian and Turkish. Making recurring trips to the Middle East, she ultimately proved indispensable to the British Government in their desire to gain Arab support for World War I, and in the aftermath where the British served as “teachers” to the Arabs. Gertrude is supposed to have described T.E. Lawrence as being able to ignite fires in cold rooms, but so could she. Her archaeology work led her to establishing the British School of Archaeology in Iraq and eventually also establishing the Iraqi Archaeological Museum in Baghdad. Receiving the Order of the British Empire was just one of her many awards and recognitions that her language and diplomatic skills facilitated the West’s presence in the Middle East, but she also recognized that perhaps the best solution was to allow them their follow their own path. Superb biographies exist on her fascinating life. RUSSIAN SOCIETY IN THE GENERATION LEADING UP TO THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION What was Russia like in the generation before and after the Russian Revolution? The Bolshevik or Russian Revolution occurred in 1917. At the time 85% of the Russians were peasants. Society was definitely patriarchal in structure. Peasant law did not consider women legal members of the household. Women did not hold property rights if any male members of the family were alive. Land was inherited only via the male line. Women only had rights over their dowries, which consisted primarily of clothing and kitchen utensils. Occasionally the dowry included a sheep or cow. If her husband died, the wife was usually not welcomed back to her natal family as in China. Her sons were not accepted by her birth family either as they had no value. 6 Most households were extended families, and were quite large with twenty-five to thirty people within this multiple-family household. This contrasted with the nuclear family of the West. The patriarch of the family had authority over the smallest detail. Father-in-laws had legal rights to have sexual intercourse with their daughters-in-law. The practice was sufficiently common to merit its own word in the Russian language: "Snokhachestvo." Adult sons had consultative voice in family matters, and dominance over their wives. Women did not participate in the governance of the household. A rigid patriarchy system of peasant society was hardly unique to Russia, but Russian women were more subordinate than in other nationalities. A woman was not only subordinate to her husband and father, but to the entire male community in the villages. Peasant households were organized into communes, governed by the elders, male heads of households. In the peasant courts of original and final jurisdiction over all civil and some criminal disputes, there were only male judges and juries. Women were thus mute and powerless and best expressed in the Russian peasant proverb: "A hen is not a bird, and a woman is not a person." Yet women's endless labor was essential to the family's survival. While women's work was valued by peasants, men's labor was valued more. Women were taught from childhood to submit to the power of men. It was God's will that a woman do as she was told, just as it was God's will that she endure privations of her life. However, the wife of the male head of the household was able to prescribe duties to the other women in the house, so mother-in-law's power and abuse of power over their sons' wives was notorious. This was true in China as well. Another popular expression in Russia further elucidates this: "And who carries the water? The Daughter-in-law. And who is beaten? The Daughter-in-law. And why is she beaten? Because she is the Daughter-in-law." What were the specific duties of peasant women? There was a long list of chores that were borne by the women folk. These included cleaning and maintenance of the home, grinding grain, preparing and preserving food, taking care of the livestock, gardens, and dairy work, and providing clothing. Peasant women's responsibilities were not just to her home and its environs, but survival of the household depended on her labor in the fields too. By tradition, field work was divided by gender. Men ploughed and sowed the land, kept bees, and took care of the sheep. Women fertilized and weeded the land. During harvest they moved the hay, stacked it, and then bound the sheaves. Afterwards they burned the stubble. Even in some places the implements used for mowing the crops were divided by sex. Women mowed hay with a sickle and men with a scythe. During this time Russian agriculture suffered from serious under production. Land was exhausted after centuries of primitive cultivation methods. Food production on the farm was not able to support the rapidly growing population, so by the 1880's peasant households were rarely self-sufficient. Land provided not even enough to pay the taxes, nor enough food for the peasants themselves. Serfs were manumitted in 7 1861, but then had to buy their land, which was only half what they had before they became free peasants. This forced peasants to buy goods they had once produced themselves, and wage labor became a necessity. This new phenomenon directly influenced the position and role of peasant women both in the household and extended economy. Households began to split up to survive economically, and became more nuclear in structure like the West. Sources seem to indicate that women had less work and responsibilities once this multiple-family structure decreased. As the economy moved more towards industrialization, men left the farms to seek employment. This then led to woman's share of field labor increasing. Now women ploughed, did road repairs, and many other necessary chores. Men left the land first because they could earn more than women, but women on the farms were forced to supplement their earnings too. Each region in Russia saw women having different experiences earning extra money to survive. In the most heavily industrialized areas of Russia, the central part, factories were located in the country side as well as in the city of Moscow. In these locations women were involved in the "putting-out" system. By the late nineteenth century the greatest number of peasant women knitted woolen gloves and stockings. Observations were vivid: "You will see row upon row of wagons loaded down with grass, hay, wood, potatoes, etc., and driving or walking beside them were women talking among themselves as their hands knitted stockings; or as women carried sacks with jugs full of milk and cream, they were seen knitting as they walked." As soon as factories began producing stockings and gloves by 1900 women no longer were involved in the cottage or the puttingout system. In less populated areas around the city of St. Petersburg on the Baltic sea, women were involved in the sale of agricultural and dairy products. Women grew and then transported the produce to market. In tourist areas, women earned extra money renting summer accommodations, and necessary ancillary services. In conclusions then, between the 1880's and the beginning of World War I, women were increasingly responsible for working the land to free men for outside wage work. Women still had to do other work to supplement their family's income, which varied according to the location. Women's wages were always considerably less then men's and where they both held the same occupation, women earned from one-fifth to two-thirds of men's wages. As more and more factories took over the cottage industries, more women were eventually forced to work in the factories. THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION ITSELF Why did this occur? As in all revolutions, there were many causes as the revolution had been brewing for a long time. It is obvious that the awful conditions of the peasants was crucial. The Tsarist regime was severely outdated and not effective. Economic conditions led to many demonstrations by 8 women for food in the cities. Many historians now credit the tradition of women's radicalism as the impulse to revolt. This radicalism was older and more powerful than anywhere else in Europe. After Sophia Perovskaya assassinated the Czar in 1881, women remained prominent in the radical movement throughout the early twentieth century. Women were terrorists and organizers of peasants and workers. One of the most prominent women was Alexandra Kollontai (1872-1952). She was part of the socialist radical movement that included Lenin and his wife Nadezhda Krupskaya. When World War I broke out in 1914, Kollontai switched from organizing women to being a peace proponent, by pointing to the war's capitalist inspiration and profits. Alexandra was out of the country too like Lenin when the actual revolution began in 1917. She returned to Russia to advocate for the socialist viewpoint and bring women to her way of thinking. From this history of women involved in radical socialist movements, Lenin himself drew the conclusion that women's role in the revolutionary activities would be crucial. On the even of World War I Lenin's wife, Nadezhda Krupskaya, his sister Anna, his devoted friend Iness, and other women published seven issues of The Woman Worker, as a way of introducing to women the Bolshevik brand of socialism. At the same time the Social Revolutionary Group organized women school teachers, and many other radicals recruited activists from the upper classes. Terrorist acts had died down before World War I because the Czarist government had by then incarcerated or exiled most of the prominent women radicals. However, their collective activity continued in waves of strikes, etc. Such activity abated due to patriotism when the war broke out, but only for a few years. When it became clear that the Tsar was not able or willing to address the horrible conditions of the peasants, the ensuing outcry forced him to create the Duma, a parliamentary-type body. This did not work well as the Representatives in the Duma were repeatedly sent home. As it became clear that Russia did not have an adequate ruler, and their soldiers did not have adequate weapons, it soon became evident how backward Russia was. One of the most interesting and unusual parts of Russian history during this time was the Royal family and their dealings with the disreputable pervert, Rasputin. Alexandra was the Tsarina and Nicholas II was the Tsar. While Alexandra's was Queen Victoria's favorite granddaughter, she was a German princess from Hesse and she was not liked by the Russians, who called her "The German." Tragically, the heir to the throne, Alexis, had hemophilia, and through the efforts of a group of ladies of St. Petersburg society, Rasputin was introduced to the imperial family, who espoused his ability to hypnotize Alexis, so that his pain was bearable. Rasputin, whose name means dissolute, was a halfliterate non-ordained religious teacher, who wandered through rural Russia, living on donations from simple-minded believers. Apparently, the essence of his preaching seems to have been the belief that "sexual indulgence is the true path to humility and through humility to eternal salvation," and he 9 claimed "The greater the sin, the greater the repentance." Eventually Rasputin's advice was sought on all matters concerning the imperial family. When Nicholas was away commanding the army at the eastern front, Rasputin's influence increased. By 1916 his orgies with both women and beasts were legendary. As military and economic disasters multiplied, widespread resentment escalated. Rasputin was murdered in December 1916 thought it took four ways; through poison in his wine, then he was stabbed with a knife, shot with a revolver, and finally he was drowned in one of the canals of the Neva River. Tsarina Alexandra went into shock as she remembered Rasputin's prophecy: "If I die or you desert me, in six months you will lose your son and your throne." It happened. During the war many Russian women even became soldiers. The most famous was Mariya Bochkareva, who was decorated for her bravery, but there were thousands of women that fought on the battlefields, even in the death battalions created by Alexander Kerensky. With the Russian casualties escalating daily, and many of the soldiers beginning to desert, it became evident to the workers and middle class that Russia was backward in technology, cultural, and politics. By March of 1917 women began demonstrating for better food supplies, and bread rationing became necessary in Petrograd (now Russianized from the German St. Petersburg). A pound of rye bread in 1813 sold for three kopeks, but by 1916 it was eighteen kopeks. Women stood in bread lines after working twelve hour days in factories. These lines became the only way to feed their families. "Men consider it better to die of hunger than to stand in line; a mother can't act that way because she is the mother of her children and she needs to feed them." Documents now available attest that the government was aware of the food problem, and women’s hostilities. In a police report of January 1917 it stated that: "Mothers of families, exhausted by endless standing in line at stores, distraught over their half-starving and sick children are today perhaps closer to revolution than [liberal opposition leaders] and of course they are a great deal more dangerous because they are the combustible material for which only a single spark is needed to burst into flames." Women in Petrograd began demonstrating after waiting hours in food lines, and then they turned to pillaging and general destruction. On International Women's Day in March 8th, 1917, about 10,000 Russian women started marching, carrying banners reading: Down with Autocracy, Down with War; Our Husbands must return from the front; Peace and Bread. These women persisted in their efforts even though male political leaders of all the various parties had told them not to. The military refused to fire on the women and others who had joined them. Commonly heard was "Put down your bayonets and join us." Women also spontaneously coordinated a series of other protests, including seizing streetcars, and confiscating food from stores. Hundreds of thousands of women filled the streets in an outburst of disobedience that the government could not control. 10 With those protests the Russian Revolution began. It spread to other cities and the Czar abdicated. Thus, while working class women made their presence felt in many nations during World War I, in Russia the women helped change history. Women's demonstration became a revolution. Women continued to take an active role after the revolution. In the cities working class women responded to the revolution differently. At one point 20,000 Petrograd women marched again demanding the vote, displaying the banner reading "The woman's Place is in the Constituent Assembly. Other women protested the war, and all political parties competed for women's support, and appointed prominent women to their central committees. The provisional government under Kerensky included two women, Ariadna Tyrkova and Countess Sofya Panina. Few women, however, ran successfully for seats in the Moscow and Petrograd Assemblies. Women did get the vote in 1917, the first European nation outside of Scandinavia to enfranchise women. Women also got an array of civil rights, including the right to equal pay. Then under the banner of "Bread and Peace" exiled radicals including Lenin and his wife Krupskaya and others returned to Russia in a sealed German railroad car to push the revolution leftward. The Germans had been paying for these radicals to incite revolution so that they would pull out of the war. After a series of maneuvers and battles, the Bolsheviks illegally took control of the government. Their position did not become secure for several years as a Civil War erupted between the Bolsheviks with Leon Trotsky as the War Commissar, and the Social Revolutionaries. In an Leninapproved election, the Bolsheviks won only 25% of the popular vote, necessitating an overthrow called the Red Terror. Trotsky made peace with the Germans (The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk 1918), which ceded to Germany huge areas of Russian land, which helped to encourage rebellion against the new regime in a civil war. The anti-Bolsheviks were joined by fourteen nations and nearly one million of their men to try and eliminate Lenin and his Bolsheviks. Within two years, the White Forces, as they were called, lost against the Red Forces, with horrible consequences for the Russians. Estimates of the number of Russians dying range from nine to fifteen million with two million starving to death, three and one-half million dying of Typhoid Fever. Within a short time, the Tsar and his entire family were imprisoned in the Ural Mountains and they were ordered killed out of fear they were about to be liberated by a counter-revolutionary army. Their remains have now been found and they are interred in the Cathedral of Sts Peter and Paul in St. Petersburg, where the rulers from the past lie buried While the battle ensued between the Red and the White Armies, Bolsheviks attempted a series of reforms. Abolition of private property and democratization of production and politics occurred too. Women participated in every step of radicalization of the Russian Revolution, but there was always a 11 small group of leaders that guided the Bolshevik program for women, families, marriages, and children. In the vanguard for these efforts was Alexandra Kollontai, who was an early revolutionary in Lenin's circle. Alexandra became a polyglot enabling her to travel around Europe and the United States on behalf of revolutionary socialism, all the while developing the theoretical and practical interest in women's issues. The extremely backward conditions under which Russian women lived led Kollontai to fear their potentially reactionary role if the socialists did not provide them a political education. The Bolsheviks did not have success with peasant women as they did with others. When the Revolution broke out peasants seized their landlord's property, and even removed the landlords who oppressed them. Unfortunately most peasant women preferred to cling to the patriarchal forms of family and village. Why? These peasants saw Bolsheviks as city folks who had loose-living styles, were atheists (the peasants were Russian Orthodox), bobbed their hair, and smoked cigarettes. The peasants thought that these Bolshevik women had sexual designs on their husbands. Some peasants felt that the Bolsheviks were even trying to destroy marriage itself, which they weren't that far off as Lenin and his Wife Krupskaya were atheists and did not wear wedding rings. Actually the Bolsheviks, at least on paper, were committed to the destruction of the patriarchal family, Orthodox Christianity, and private land ownership. If a peasant woman had anything to do with the Bolsheviks and their reforms, then they were beaten or even expelled from their homes by their husbands and fathers. There were many reforms that affected women as a result of the Russian Revolution. Marriage became a civil not religious rite. Divorce was obtainable upon request by both partners. In 1920 abortion was made legal in hospitals, although they called abortion itself "an evil." This legalization of abortions meant that Russia was the first country in Modern Europe to do so. Women also gained legal rights over their children and equality in courts. As their duty for citizenship, all Russians were to work. Since most women had always worked, this provision was hardly new, but it gave legitimacy to women working for pay. Mothers began to receive benefits from a series of supportive measures: prenatal education, and free maternity hospital care. The Bolsheviks recognized and stated "that the work of motherhood was every bit as important as that of an engineer who constructs roads." Then a campaign to educate women began. At this time 85% of women were illiterate. Education for women meant they could be engineers, veterinarians and doctors. Even a Women's Bureau, the Zhenotdel, was set up to help women deal with the patriarchal Russian family structure. This Bureau educated women on their rights and taught them a variety of liberating skills such as: how to organize a day-care center. The Zhenotdel attracted attention throughout the world, but in the Far East, Zhenotdel workers were hacked to death, stoned and beaten for encouraging women to take off their veils and challenge tribal customs. 12 Once Lenin died in 1924, and Kollontai fell from favor, the government's priority was now productivity and industrialization. Independent women's organizations were abolished, including the International Women's Secretariat in 1926. Under Lenin, Trotsky and Stalin, Russia became the Soviet Union. Nationalized of the land, the banks, and factories occurred. Confiscation of all church property followed next. The capital was moved from Petrograd to Moscow and the Bolsheviks became communists.