Indirect Realism revision sheets

advertisement

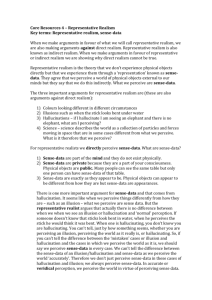

1. Indirect Realism Indirect Realism (IDR) is a realist theory of perception: at least some of what we perceive is a feature of the external world and exists independently of our mind. However it is different to DR as IDR argues we indirectly perceive mind-independent physical objects through the medium of sense data. Ultimately IDR argues that there is something between the perceiver and the thing perceived. Key term: Sense data - what we are immediately aware of in perception i.e. the colour and shape of the desk as I see it now. (The mental representation) Therefore: We directly perceive sense data And we indirectly perceive the mind-independent physical object causing the sense-data In other words…..Our perception of reality is mediated by sense data, so that we must infer the existence and nature of the external world on the basis of the way it is represented to us in the mind. The distinction between primary and secondary qualities The distinction between primary and secondary qualities is important in understanding IDR as a realist theory of perception because it enables the IDR to claim that the external world really does exist independently of our minds. How? Well, this distinction explains sense data and thus can explain the differences in perceptual variation, the experience of illusions and hallucinations and the concept of a time-lag without jeopardising the existence of mind-independent physical objects. What are they? Primary qualities: • Qualities that exists independently of our perceiving them. In simpler terms, it refers to properties like shape, size and motion, that don’t depend on our senses. Secondary qualities: • Qualities that require a perceiving mind to perceive them i.e. experience of the senses. In simpler terms, it refers to properties like colour, smell and taste that do depend on our senses. Characteristics of primary and secondary qualities: Primary Qualities Secondary Qualities Explain how physical objects interact with each other. Explain how physical objects interact with us. Can be described precisely and mathematically. Can’t be described with this precision. Are ascribed to objects by science. Are not ascribed to objects by science. Are (arguably) essential to physical objects. Are (arguably) not essential to physical objects. Exist independently of the perceiver, in the objects themselves. (Arguably) Exist only in the mind of the perceiver and not in the objects themselves. Descartes on the distinction between primary and secondary qualities: Using the example of fire, Descartes argues that there is a distinction between the primary and secondary qualities of a mind-independent object. He argues that the sensation of heat within a perceiver cannot accurately resemble any real property of the fire. Why? Well, Descartes points out that we do not assume that the pain the fire may cause us is part of the fire itself. Therefore the ability to feel heat from a fire comes under the same line of logic: the heat the fire causes in us (just like the pain) is also not in fire. ‘And although in approaching fire I feel heat, and in approaching it a little too near I even feel pain, there is at the same time no reason in this which could persuade me that there is in the fire something resembling this heat any more than there is in it something resembling the pain; all that I have any reason to believe from this is, that there is something in it, whatever it may be, which excites in me these sensations of heat or of pain.’ Descartes – Meditation 6 Locke on the distinction between primary and secondary qualities: *Note – this will be used in response to issue 2.1 - It leads to scepticism about the ‘nature’ of the external world Locke argues: A ‘quality’ is a power that a physical property has to produce an idea in our minds. Primary qualities are qualities that are inseparable from the subject whatever changes it undergoes. ‘The object has these properties “in and of itself”.’ For Locke they are: Extension (occupies space no matter what the condition). Shape Motion Number Solidity (the quality of a physical object whereby it takes up space and excludes other physical objects from occupying exactly the same space). *Be aware that later on in his work Locke adds texture, size and situation to this list and leaves out number, extension and solidity. He argued that these are all primary qualities – they are inseparable from the physical object – because physical objects must always ‘have some size and shape, they must always be at rest or in motion of some kind, they can be counted.’ Locke uses the example of dividing up a grain of wheat to help explain: ‘Qualities thus considered in bodies are, first, such as are utterly inseparable from the body, in what state soever it be….e.g. take a grain of wheat, divide it into two parts; each part has still solidity, extension, figure, and mobility: divide it again, and it retains still the same qualities; and so divide it on, till the parts become insensible; they must retain still each of them all those qualities.’ Locke, Essay, II.viii.9 Therefore no matter how many times we cut up and divide the grain of wheat up, the primary qualities will remain. The yellow colour of the grain of wheat will vary, change and disappear but its extension etc will remain. Secondary qualities are not qualities of the physical object itself, but exist only in the act of perception. They come into existence through the effect of a physical object on a perceiver: ‘…such qualities which in truth are nothing in the objects themselves, but powers to produce various sensations in us by their primary qualities, i.e. by bulk, figure texture, and motion of their insensible parts, as colours, sounds, tastes etc. these I call secondary qualities.’ Locke, Essay, II, viii.10 Going further….. The distinction is similar to the relationship between a word and the idea that the word ‘invokes’ in our mind i.e. we say the word football – we know the word doesn’t resemble the mind-independent object (the football) but it is arbitrarily associated with it. In simpler terms we call a football a football without analysing or really thinking about it being a football because our prior knowledge of the world around us tells us it is a football. So too can we use this logic to explain how the white colour of a football doesn’t resemble the quality of the football which produces it. For this reason, we cannot directly know what it is that causes us to see white. Therefore it would appear that objects physically possess some qualities, whereas other properties are related to the minds perceiving them. Qualities of objects that cause certain sensations in us (secondary) have something to do with the minute particles from which they are composed of and their movements (primary). Indirect realism, through primary & secondary qualities, develops a ‘two-world’ view of perception: World No. 1 = the world as it really is. Objects with primary qualities obey the laws of physics here in a sense-less world i.e. no colour, taste or smell. But it is this world, in conjunction with our perceptual system that causes us to perceive ‘World Number 2’. World No. 2, the world we directly perceive, is a representation of World No. 1, the world as it is. 1.1 It leads to scepticism about the ‘nature’ of the external world (attacking ‘representative’) If we accept IDR, then all we know about and are aware of is sense data i.e. a representation of reality in my mind. However, this means I cannot have immediate access to the external real world and reality. This leads to the question – ‘But if I cannot have immediate access to reality, then how am I to determine how accurate the representation of it is in my mind?’ Scepticism – the view that we cannot know, or cannot show that we know, a particular claim. We seem to have no way of checking whether our sense-data accurately represents the world – and so, no way of knowing that they do. Analogy of the cinema: Imagine that you have spent your whole life locked inside a cinema. Inside the cinema, films are continually rolling, telling you about the outside world – but you are never able to check the accuracy of these films for yourself. In fact, the films are completely accurate, and it never occurs to you to doubt their accuracy. Given that this is so, is it fair to say that, through them, you know what the world is like outside the cinema? Some would say that, if indirect realism is true, we are like the character described in the analogy above. You are trapped in a cinema with no way of telling whether the images projected are genuine pictures of the outside world. How does indirect realism lead some to question whether sense data resembles the primary qualities of objects? If I cannot have immediate access to reality, how can I determine how accurate the representation of it is in my mind? If we can doubt that secondary qualities resemble reality, how does it prevent us having the same doubt with primary qualities? Locke relies on ‘the corpuscular physics’ to defend this distinction. i.e. universe is made up of imperceptible atoms that possess the properties of size, shape etc and secondary qualities are the microstructures of these particles which cause sensations in us. However, if the link between secondary qualities and reality is not one of resemblance, how can we be certain of what causes us to perceive these secondary qualities? Therefore questions arise of how sure we can be that the sense data we perceive of objects resemble their sense data. To be certain we would need a ‘God’s-eye view’ of the world, which is impossible. Locke and Russell are empiricists and so argue that all knowledge of the world can only come to us through experience. However, since we only have immediate and certain knowledge of sense data one cannot experience the relationship between sense data and reality. Hume argues a similar point: It is a question of fact, whether the perceptions of the senses be produced by external objects, resembling them: how shall this question be determined? By experience surely; as all other questions of a like nature. But here experience is, and must be entirely silent. The mind has never anything present to it but the perceptions, and cannot possibly reach any experience of their connexion with objects. The supposition of such a connexion is, therefore, without any foundation in reasoning. Hume’s Enquiry, I, xii, part 1, paragraph 119 This leads onto the sceptical worry which is outlined in the concept: ‘veil of perception’. The veil of perception: • Indirect realism risks making the external world inaccessible to us. • It is as though an impenetrable veil has dropped down between us and the world we only have access to our representations. Two defences: 1. We would not survive • • • If the world we perceive did not match the external world, then we would have been unable to hunt & gather. The human species would have died out years ago. Therefore the correspondence between the two worlds (i.e. the external world and the world as we perceive it) must be sound. However it still doesn’t tell us how accurate our perception is………. Different species have different ways of perceiving the external world. 2. Appealing to the testimony of other people • If everyone perceives the world roughly as we do then we have some evidence that the world is in fact how it appears. • However, the perception of second observer will have the same difficulties as me. • Example of the matrix – useless for people in the matrix to appeal to fellow matrix citizens. Responses: Locke between primary and secondary qualities See previous notes above on Locke’s distinction between the two qualities. Responses: Sense data tells us of ‘relations’ between objects (Russell) Russell calls what we are immediately aware of within the mind a ‘private space’ that consists of sense data. The shapes we perceive and the relative distances between the objects will vary between different individuals’ private spaces, and within my own as I walk around the table. - For objects in physical space to cause our sense data we must exist in physical space as well. - The relative positions of physical objects in space in the real external world – left, right, just in front etc – ‘correspond to’ the relative positions of sense-data in apparent space. I.e. it will take me longer to walk through physical space to the corner shop that appears further away than the corner shop that appears closer. Therefore there is a correspondence between my private space (of sense data) and physical space. From this we can make reliable judgements about ‘the shapes and relative positions’ of real physical, mind-independent objects. **His arguments in this response are similar to/are his contribution to the argument from perceptual variation. Russell also distinguishes between private and public time: ‘real’ time is distinct from our ‘feeling of duration’. We are immediately aware of our own feeling of how long something took i.e. how time appears subjectively to pass. For instance, if we are really enjoying a philosophy lesson, the hour lesson will seem to pass quickly! We can never know the ‘real time’ in which physical objects exist but we can know about ‘relative’ times i.e. whether something comes before or after something else. Therefore we can have an idea of the nature of the external world through the relation between real time and relative time. 1.2 It leads to scepticism about the ‘existence’ of the external world (attacking ‘realism’) Again, if we accept IDR, then what we perceive directly is sense-data as this is all we know about. However, IDR believes that behind the sense data there are real physical objects that cause our sense data. But how can we truly know this? To know that physical objects cause sense-data, we first need to know whether physical objects exist or not. Even if we can show that our sense-data are caused by something that exists independently of us and our minds, how can we establish the thing that causes it? Russell raises this problem in Chapter 2, The Problems of Philosophy: ‘Granted that we are certain of our own sense-data, have we any reason for regarding them as signs of the existence of something else, which we can call the physical object? Responses – external world is the ‘best hypothesis’ (Russell) Russell offers an initial solution – appealing to the testimony of other people. He argues that if a collection of people sat around a dinner table, we would all perceive something more or less similar i.e. we would all, ultimately, be perceiving the same table. They will have very similar sense-data if they are at the same place and time. Therefore Russell argues that it is reasonable to suppose that there is a real object which causes these similar perceptions. However, Russell quickly dismisses this solution as it presupposes that people really do exist. If I am questioning whether there really exist physical objects that are independent of my sense data, I must also question the existence of people (for they are physical objects too!): ‘Thus, when we are trying to show that there must be objects independent of our own sense-data, we cannot appeal to the testimony of other people, since this testimony itself consists of sense-data, and does not reveal other people’s experiences unless our own sense-data are signs of things existing independently of us.’ Russell, The Problems of Philosophy, Chp 2, p.10 So Russell offers a second argument (taken from Lacewing p.41): 1. Either physical objects exist and cause my sense-data or physical objects do not exist nor cause my sense-data. 2. I can’t prove either claim is true or false. 3. Therefore, I have to treat them as hypotheses. (A hypothesis is a proposal that needs to be confirmed or rejected by reasoning or experience.) 4. The hypothesis that physical objects exist and cause my sense-data is better. 5. Therefore, physical objects exist and cause my sense-data. **Note – this can be easily transformed into standard form. Statement 4 can be verified by testing a hypothesis to see whether it explains why my experience is the way it is. For example: ‘I see a cat first in a corner of the room and then later on the sofa, then if the cat is a physical object, it travelled from the corner to the sofa when I wasn’t looking. If there is no cat apart from what I see in my sense-data, then the cat does not exist when I don’t see it. It springs into existence first in the corner, and then later on the sofa. Nothing connects my two perceptions. But that’s incredibly puzzling – indeed, it is no explanation at all of why my sense-data are the way they are! So the hypothesis that there is a physical object – the cat – that causes what I see is the best explanation of my sense-data.’ (Lacewing p.41) Therefore the explanation that physical objects cause my sense data not only seems more logical but it can be tested too. **This example can also be used as a criticism of idealism (the continued existence of things). Responses – coherence of the various senses and lack of choice over our experiences (Locke) Locke accepts that his argument is not a complete proof but rather an argument to the best explanation. Lack of choice over our experiences: the fact that I cannot control the sensations that I experience suggests that there is something external to me which produces them. - However even if we accept Locke’s assumption, the hardened sceptic is still going argue that this argument does not necessarily show that it is the universe/external real world that is causing the sensations in us. The coherence of various senses: ‘Our senses in many cases bear witness to the truth of each other’s report concerning the existence of sensible things without us.’ It may be likely that one or two senses could fool us; however it is unlikely that four or five senses could fool us or lie to us. - The hardened sceptic may still worry that our sense experiences still conspire to create the illusion of a physical world (See Descartes Cartesian Demon for further information). However, Locke dismisses these on practical grounds: we must suppose the external world is real as it is on this basis that we are able to live and fulfil our functions. 2.3 Problems arising from the view that mind-dependent objects represent mindindependent objects and are caused by mind-independent objects. These arguments all require that our minds are causally affected by physical objects i.e. I perceive a Granny Smith apple (the mind-independent object & its primary qualities) through sense data (secondary qualities). The physical objects causally affect our sense organs that consequently affect our brains. But, ‘how does what happens in our brains causally affect our conscious perception?’ How can something physical cause an idea in our brains? This is a perennial question for IDR (& DR too) and whether it is a valid theory of perception. Berkeley’s idealism attempts to dismiss this criticism through rejecting realism and adopting idealism.

![Some Qualities of a Good Teacher[1]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005352484_1-a7f75ec59d045ce4c166834a8805ba83-300x300.png)