ppt file - UC Davis

advertisement

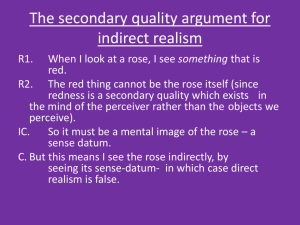

The Problems of Philosophy Philosophy 1 Spring, 2002 G. J. Mattey Bertrand Russell • • • • • Born 1872 From England Aristocrat Anti-war activist Won Nobel Prize for literature (1950) • Author of popular essays • Died 1970 Russell’s Contributions • Discovered, and tried to solve, “Russell’s paradox” in the theory of sets • Published first widely-read treatise on symbolic logic (with A. N. Whitehead) • Tried to reduce mathematics to logic (logicism) • Applied symbolic logic to philosophical problems • Co-founder of analytic philosophy (with G. E. Moore) Perceptual Relativity • We think that our ordinary beliefs are certain, e.g., I am sitting at a table of a specific shape • But these beliefs are very likely to be wrong • We describe the table on the basis of what we see and feel, and we think others would describe it in the same way • But the description only reflects our own point of view • No two people see and feel it the same way Appearance and Reality • A painter is concerned with appearance, a practical person with reality • The philosopher wants to know what appearance and reality are • Perceptual relativity shows that color is merely appearance: the table has no single color • The same considerations hold for shape, hardness • The real table is not immediately known by sense Two Questions • Is there a real table at all? • If there is a real table, what are its real characteristics? • Both are very difficult to answer Sense-data • Sense-data are things immediately known in sensation • Sensation is the experience of being immediately aware of sense data • Colors, shapes, textures are sense-data • So, a sensation of color is the sensation of a sensedatum • The sense-data are not the table or properties of the table, so how are they related to the table? Idealism • Objects such as tables are physical objects • The collection of physical objects is matter • Berkeley tried to show that matter does not exist at all, and at least succeeded in showing that its existence is not certain • He admits that sense-data are signs of something mental outside us • The real table is an idea in the mind of God Existential Doubt • If we cannot be sure that matter exists, we cannot be sure that other people exist • We may be all that exists (solipsism) • Even the “I” might be doubted • All that is certain is that a sense-datum is being perceived at a time • This is the solid basis for knowledge From Sense-Data to Matter • Do sense-data provide good evidence that physical objects exist? • Common sense, on the basis of practice, answers in the affirmative • There must be matter for there to be public objects that are neutral with respect to point of view • Why believe there are such objects? Similarity • One argument for public objects is that there is similarity in people’s sense-data • But this begs the question, because it supposes that there are other people receiving sense-data • They may be part of my dreams • So evidence for public objects must come from our own private experiences Simplicity • There is no contradiction in supposing that my private experiences have no public counterpart • My dreams present elaborate scenes • But it is simpler to explain my sense-data through public objects • The simplicity is due to the continued existence of public objects, which accounts for gaps in sensedata • It also accounts for behavior such as that of a cat’s exhibiting hunger Human Behavior • The real advantage of public objects is in the explanation of human behavior • Sounds and motions are produced that are most simply explained by reference to a body similar to my own • Public objects can also account for dreams • “Every principle of simplicity urges us to adopt the natural view” Belief in Physical Objects • Our original belief in physical objects is instinctive, not demonstrative • It seems that the sense-datum is the independent object (Hume) • There is no good reason to reject the natural belief, given its explanatory simplicity • It is the task of philosophy to show how our deepest instinctive beliefs form a system • The possibility of error is diminished by the harmony of the parts of the system The Nature of Physical Objects • Science has drifted into reducing the phenomena of nature to motion • The motions of physical objects are not identical to sense-data (e.g., the light itself) • Nor is the space we see and feel the space in which physical objects exist – The space we feel and the space we touch are distinct (Berkeley) • Private shapes differ when public shapes are static Correspondence • Physical objects cause sensation through interaction with a physical body • Changes in sense-data should reflect changes in bodily position relative to objects • The senses testify in favor of one another • Other people confirm what we belief • So we may assume that there is a physical space corresponding to our private space Knowledge of Physical Space • We can know of physical space only what is required to explain the correspondence • For example, we can know that the moon, earth, and sun are in a line to explain the appearance of an eclipse • But our knowledge is limited to relations of distance and does not extend to distances themselves Knowledge of Time • The private feeling of duration is a poor guide to public durations • But the order of public events corresponds to that of private experiences, “so far as we can see” (and this holds for space) • The correspondence is not exact – Lightning is really simultaneous with thunder – The light we see left the sun eight minutes ago Knowledge of Physical Objects • Differences in sense-data correspond to some differences in physical objects • We have no direct acquaintance with the properties in the physical objects • We know only the relations they hold to one another • The intrinsic properties cannot be known through the senses • It is gratuitous to think that any sense-data resemble properties of physical objects Idealism • Idealism is the doctrine that what exists (or is known to exist) is in some sense mental • This doctrine is absurd from the point of view of common sense • But we only know of public objects that they correspond to sense-data • We cannot reject the doctrine that the intrinsic character of public objects is mental simply because it is strange Berkeley’s Argument for Idealism • The existence of sense-data depends on us • Sense-data are immediately-known ideas • All we know immediately about common objects (e.g., a tree) is the sense-data • There is no reason to think that we know anything else about them • So the being of a tree is its being perceived • Its public character is explained through God Fallacies • To know a tree, it must be “in” our minds, but only as thought of • But it does not follow that it is “in” our minds as a private object – When I have my wife in mind, she does not exist there solely as a private object • An idea exists in the mind as an act, but its object may be “before the mind” while it exists outside the mind Acquaintance • An argument for idealism is that what we are not acquainted with is of no importance for us, and so does not exist • It is granted that we do not know in the sense of being acquainted with matter • But it is of importance to us • And we can know things with which we are not acquainted—we can know by description through general principles Knowledge of Things • The simplest kind of knowledge of things is by acquaintance, as with sense-data • Knowledge of things by description requires knowledge of truths: general principles • Acquaintance with does not yield knowledge of truths – I know the color directly but I do not thereby know any truth about the color Knowledge by Description • We know things by description as “the soand-so” • The table is “the physical object which causes such-and-such sense-data” • To know the table, we must know general truths about causality • Knowledge by description rests on knowledge by acquaintance as a foundation Objects of Acquaintance • Our knowledge would be very limited if we were only acquainted with sense-data • Memory extends sense-data • We also have higher-order acquaintance with our states of being aware (self-consciousness) • For example, acquaintance with seeing the sun is with the fact “Self-acquainted-with-sense-datum” • I know that I am acquainted with this sense-datum Definite Descriptions • We are also acquainted with universals such as whiteness, diversity, brotherhood • This is required for the use of language • A definite description is of the form “the so-andso” • When we know an object by description, we know it as “the so-and-so” • Definite descriptions imply existence and uniqueness Knowledge by Description • Descriptions can be nearer or further from the things with which we are acquainted • We know the things described only through the components of a description with which we are acquainted • But we can use descriptions to go beyond the limits of private experience, as in the case of physical objects