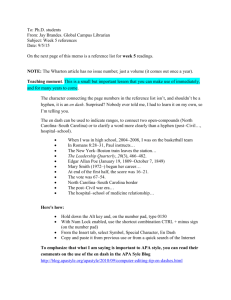

Mind Reading - Department of Cognitive Science

advertisement

“Mind Reading” through the lens of cognitive science Dana Samson Course description: How do we infer other people’s mental states? The course will provide the opportunity to make an in-depth analysis of the cognitive processes underlying “mind reading” on the basis of a selected review of classic and state of the art empirical findings and theoretical models. Compared to other domains of cognition such as memory, language, or perception, the field of “mind reading” has far less been subject to a cognitive analysis. During the course, classic concepts of cognitive psychology will be used to (a) examine current theories and empirical evidence (in adults), (b) highlight points of agreement, disagreement, and needs for clarification (c) explore future avenues to develop cognitive models of “mind reading”. Learning outcomes: At the end of the course, the student will be able to apply concepts of cognitive psychology to analyze experimental designs, empirical findings and theories in the field of mind reading. Teaching activities: Lectures, class and group discussions and individual readings. Assessment: Students will be graded on the basis of their individual participation in the class discussion during the different sessions (20% of the mark). Students (in groups of 2 or 3) will also be asked to write and orally present an experimental design that would shed a new light on the cognitive processes involved in mind reading (60% of the mark). Finally, each student will be asked to peer-review one of the proposals and the quality of the peer-review will be marked (20% of the mark). Contact: Dana.samson@uclouvain.be Drop in times will be advertised during the first session. Sessions outline: Note: references mentioned for each session are the articles that will be presented during the lectures and discussed in class. Articles with a * are those that students are expected to have read before the session to facilitate class discussions. The other articles are optional and are listed for students who wish to go beyond the material presented in class. Session 1: About Mind Reading Terminology: Theory of Mind, perspective taking, mentalizing, mind reading, empathy *Premack, D., & Woodruff, G. (1978). Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 4, 515–526. Decety, J., & Lamm, C. (2006). Human empathy through the lens of social neuroscience. The Scientific World Journal, 6, 1146–63. doi:10.1100/tsw.2006.221 Why a cognitive analysis? Heterogeneity in clinical populations, involvement of a widespread brain network, unsatisfactory Theory Theory/Simulation distinction, mind reading in nonhuman species and infants Apperly, I. A. (2008). Beyond Simulation-Theory and Theory-Theory: why social cognitive neuroscience should use its own concepts to study “theory of mind”. Cognition, 107(1), 266–83. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2007.07.019 Apperly, I. A. (2009). Alternative routes to perspective-taking: Imagination and ruleuse may be better than simulation and theorising. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 27(3), 545–553. doi:10.1348/026151008X400841 Schurz, M., Radua, J., Aichhorn, M., Richlan, F., & Perner, J. (2014). Fractionating theory of mind: a meta-analysis of functional brain imaging studies. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 42, 9–34. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.01.009 What does the cognitive analysis entail? Identifying components, characterizing the nature of the components, describing the relation between components, task analysis. Session 2: Level 1 visual perspective taking Automaticity (effortfulness, voluntariness, triggering factors) Qureshi, A. W., Apperly, I. A., & Samson, D. (2010). Executive function is necessary for perspective selection, not Level-1 visual perspective calculation: Evidence from a dual-task study of adults. Cognition, 117(2), 230–6. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2010.08.003 Ramsey, R., Hansen, P., Apperly, I., & Samson, D. (2013). Seeing it my way or your way: frontoparietal brain areas sustain viewpoint-independent perspective selection processes. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 25(5), 670–84. doi:10.1162/jocn_a_00345 *Samson, D., Apperly, I. A., Braithwaite, J. J., Andrews, B. J., & Bodley Scott, S. E. (2010). Seeing it their way: Evidence for rapid and involuntary computation of what other people see. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 36(5), 1255–66. doi:10.1037/a0018729 Domain-specificity Santiesteban, I., Catmur, C., Coughlan Hopkins, S., Bird, G., & Heyes, C. (2013). Avatars and Arrows: Implicit Mentalizing or Domain-General Processing? Journal of Experimental Psychology. Human Perception and Performance, 39(6), 1–9. doi:10.1037/a0035175 Session 3: Level 2 visual perspective taking Automaticity (effortfulness, voluntariness, triggering factors) *Furlanetto, T., Cavallo, A., Manera, V., Tversky, B., & Becchio, C. (2013). Through your eyes: incongruence of gaze and action increases spontaneous perspective taking. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7(August), 455. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2013.00455 Surtees et al. (manuscripts submitted to be discussed in class) Session 4: Visual and spatial, Level 1 and Level 2 perspective taking Do we put ourselves in the other’s shoes? Line of sight and embodiment *Kessler, K., & Thomson, L. A. (2010). The embodied nature of spatial perspective taking: embodied transformation versus sensorimotor interference. Cognition, 114(1), 72–88. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2009.08.015 Michelon, P., & Zacks, J. M. (2006). Two kinds of visual perspective taking. Perception & Psychophysics, 68(2), 327–37. Surtees, A., Apperly, I. a, & Samson, D. (2013). Similarities and differences in visual and spatial perspective-taking processes. Cognition, 129(2), 426–38. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2013.06.008 Surtees, A., Apperly, I. a, & Samson, D. (2013). The use of embodied self-rotation for visual and spatial perspective-taking. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7(November), 1–12. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2013.00698 Session 5: Belief reasoning (part 1) Automaticity (effortfulness, voluntariness, triggering factors) Apperly, I. A., Riggs, K. J., Simpson, A., Chiavarino, C., & Samson, D. (2006). Is Belief Reasoning Automatic? Psychological Science, 17(10), 841–844. Kovács, Á. M., Téglás, E., & Endress, A. D. (2010). The social sense: susceptibility to others’ beliefs in human infants and adults. Science, 330(6012), 1830–4. doi:10.1126/science.1190792 Phillips, J., Ong, D. C., Surtees, A. D. R., Xin, Y., Williams, S., Saxe, R., & Frank, M. C. (in press). A second look at automatic theory of mind: Reconsidering Kovacs, Teglas and Endress. Psychological Science. Schneider, D., Lam, R., Bayliss, A. P., & Dux, P. E. (2012). Cognitive Load Disrupts Implicit Theory-of-Mind Processing. Psychological Science, 23(8), 842–7. doi:10.1177/0956797612439070 *Schneider, D., Nott, Z. E., & Dux, P. E. (2014). Task instructions and implicit theory of mind. Cognition, 133(1), 43–7. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2014.05.016 Van der Wel, R. P. R. D., Sebanz, N., & Knoblich, G. (2014). Do people automatically track others’ beliefs? Evidence from a continuous measure. Cognition, 130(1), 128– 133. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2013.10.004 Session 6: Belief reasoning (part 2) Beyond the explicit-implicit divide: Two-systems model and limit signature Apperly, I. A., & Butterfill, S. A. (2009). Do humans have two systems to track beliefs and belief-like states? Psychological Review, 116(4), 953–970. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0016923 Butterfill, S. a., & Apperly, I. a. (2013). How to construct a minimal Theory of Mind. Mind & Language, 28(5), 606–637. doi:10.1111/mila.12036 + response to commentaries: http://www.butterfill.com/pdf/minimal_brains_discussion_replies.pdf Kovács, A. M., Kühn, S., Gergely, G., Csibra, G., & Brass, M. (2014). Are all beliefs equal? Implicit belief attributions recruiting core brain regions of theory of mind. PloS One, 9(9), e106558. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0106558 Low, J., & Watts, J. (2013). Attributing false beliefs about object identity reveals a signature blind spot in humans’ efficient mind-reading system. Psychological Science, 24(3), 305–11. doi:10.1177/0956797612451469 Submentalizing *Heyes, C. (2014). Submentalizing: I am not really reading your mind. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 9(2), 131–143. doi:10.1177/1745691613518076 Session 7: Self and other (part 1) Self as anchoring point Epley, N., Keysar, B., Van Boven, L., & Gilovich, T. (2004). Perspective taking as egocentric anchoring and adjustment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(3), 327–39. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.87.3.327 Epley, N., & Caruso, E. M. (2009). Perspective taking: Misstepping into others’ shoes. In K. D. Markman, W. M. P. Klein, & J. A. Suhr (Eds.), Handbook of imagination and mental simulation (pp. 295-309). New York: Psychology Press. Available online: http://faculty.chicagobooth.edu/eugene.caruso/docs/Epley%20&%20Caruso%20(20 09)%20Misstepping%20into%20Others'%20Shoes.pdf Self-bias and other-orientation Cunningham, S. J., Turk, D. J., Macdonald, L. M., & Neil Macrae, C. (2008). Yours or mine? Ownership and memory. Consciousness and Cognition, 17(1), 312–8. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2007.04.003 Mattan, B., Quinn, K. A., Apperly, I. A., Sui, J., & Rotshtein, P. (in press). Is It Always Me First? Effects of Self-Tagging on Third-Person Perspective-Taking. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition. doi:10.1037/xlm0000078 (manuscript will be provided) *Sui, J., Rotshtein, P., & Humphreys, G. W. (2013). Coupling social attention to the self forms a network for personal significance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 110(19), 7607–12. doi:10.1073/pnas.1221862110 Session 8: Self and other (part 2) Self-other attribution/distinction Schuwerk, T., Schecklmann, M., Langguth, B., Döhnel, K., Sodian, B., & Sommer, M. (2014). Inhibiting the posterior medial prefrontal cortex by rTMS decreases the discrepancy between self and other in Theory of Mind reasoning. Behavioural Brain Research, 274, 312–8. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2014.08.031Self monkey cell Self-perspective inhibition Hartwright, C. E., Apperly, I. A, & Hansen, P. C. (2014). The special case of self perspective inhibition in mental, but not non-mental, representation. Neuropsychologia, 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2014.12.015 *Hartwright, C. E., Apperly, I. A, & Hansen, P. C. (2012). Multiple roles for executive control in belief-desire reasoning: distinct neural networks are recruited for self perspective inhibition and complexity of reasoning. NeuroImage, 61(4), 921–30. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.03.012 Leslie, A. M., German, T. P., & Polizzi, P. (2005). Belief-desire reasoning as a process of selection. Cognitive Psychology, 50(1), 45–85. doi:10.1016/j.cogpsych.2004.06.002 Samson, D., Houthuys, S., & Humphreys, G.W. (accepted). Self-perspective inhibition deficits cannot be explained by general executive function deficits. Cortex. (manuscript will be provided) Session 9: Insights from the neuropsychological approach (part 1) Methodological considerations: Study of dissociations, single case vs. case series vs. group studies Functional and neural necessity Samson, D. & Apperly, I.A. (unpublished). The cognitive and neural basis of theory of mind: Insights from cognitive neuropsychology (manuscript will be provided) Session 10: Insights from the neuropsychological approach (part 2) Isolation of mind reading reading components Samson, D., & Michel, C. (2013). Theory of Mind: Insights from patients with acquired brain damage. In S. Baron-Cohen, H. Tager-Flusberg, & M. Lombardo (Eds). Understanding other Minds 3e, Oxford University Press. (manuscript will be provided) Session 11: New directions for future research (part 1) Deadline for group coursework submission No class – time should be used for each student to peer-review one proposal Session 12: New directions for future research (part 2) Oral group presentations of the research proposals and class discussion