realismquotes11-12

advertisement

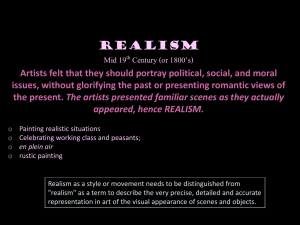

The European Novel Realism and the Nineteenth-Century Novel The ideal is gone, lyricism has run dry. We are soberer. A severe, pitiless concern for truth, the most modern form of empiricism, has penetrated into art. Charles Saint-Beuve (1857) Painting is an essentially concrete art and can only consist of the presentation of real and existing things. It is a completely physical language, the words of which consist of all visible objects; an object which is abstract, not visible, non-existent, is not within the realm of painting. Gustave Courbet (1861) Let us imagine that impersonality is the sign of force. Let us absorb the objective, let it circulate in us, let it reproduce itself on the outside without anyone being able to understand anything about this marvellous chemistry. Our heart must be good only for feeling that of others. Let us be magnifying mirrors of exterior reality. Flaubert, quoted in Roe (1989) [Realism] was a type of literature that aimed to integrate the external world into the text – breaking both with the visionary impetus of the romantic writer and with his confidence in the primacy of self […] the central tenet of the Realist aesthetic: its concern for verisimilitude, for probability, and for ‘close observation and the careful reproduction of minute detail and local colour’ (Honoré de Balzac), but also the modest theoretical nature of its artistic ambit: the world is simply there; we need only open our eyes to see and describe it […] The operative terms of Romantic literature: ‘imagination’, ‘fantasy’, and ‘dream’ […] found their equivalents in the infinitely more passive mechanisms of ‘reflection’, ‘mirror’, and ‘reproduction’, terms which appeared whenever Realism required a theoretical defence […] reservations regarding the Romantic mind, with its tenuous grasp on the world of recognisable reality, were shared by all the major Realist writers. Martin Travers (1998) For many centuries of European art and especially literature, imitation of the everyday, of the real in the sense of what we know best, belongs to low art, and to low style: comedy, farce, certain kinds of satire. […] The instinct of realist reproduction may be a constant in the human imagination […]. What seems to change with the coming of the modern age – dating that from sometime around the end of the eighteenth century, with the French Revolution as its great emblematic event, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau and the English Romantic writers as its flag bearers – is a new valuation of ordinary experience and its ordinary settings and things. This new valuation is of course tied to the rise of the middle classes to cultural influence, and to the rise of the novel as the preeminent form of modernity. What we see at the dawn of modernity – and the age of revolutions – is the struggle to emerge of imaginative forms and styles that would do greater justice to the language of ordinary men (in William Wordsworth’s terms) and to the meaning of unexceptional human experience. Peter Brooks, Realist Vision (2005) As it was I was somewhat interested in the scene; it sometimes lulled, although it could not extinguish my grief. During the first day we travelled in a carriage. In the morning we had seen the mountains at a distance, towards which we gradually advanced. We perceived that the valley through which we wound, and which was formed by the river Arve, whose course we followed, closed in on us by degrees; and when the sun had set, we beheld immense mountains and precipes overhanging us on every side, and heard the sound of the river raging among rocks, and the dashing of waterfalls around. Shelley, Frankenstein, Vol II, Ch I The little town of Verrières could pass for one of the prettiest in the Franche-Comté. Its white houses, with their pointed red-tiled roofs, are spread along the slope of a hill whose every undulation is marked by clumps of healthy chestnut trees. The river Doubs flows a few feet beneath fortifications built long ago by the Spaniards but now in ruins. Verrières is sheltered to the north by a high mountain, one of the spurs of the Jura. The ragged summits of the Verra become covered in snow after the first cold days in October. A torrential stream dashing down from the mountain runs through Verrières before discharging into the Doubs, and supplies power to a large number of sawmills – an industry which is extremely uncomplicated, but which provides a certain well-being for the greater part of the inhabitants, who are more like peasants than townspeople. But it is not these sawmills that have made the little town rich. It is owing to the manufacture of a painted cloth, known as Mulhouse, that, since the fall of Napoleon, a general affluence has allowed the refurbishment of nearly all the facades of the houses in Verrières. Hardly have you entered the town than you are deafened by the racket of a noisy machine of terrible aspect. Twenty massive hammers, falling with a boom that makes the street tremble, are raised up in the air again by a wheel driven by the torrential current. Every day each of these hammers makes I don’t know how many thousands of nails. Fresh, pretty young girls feed the gigantic hammer blows with little pieces of iron that are promptly transformed into nails. This crude looking industry is one of those that most surprises a traveller penetrating for the first time into the mountains between France and Switzerland. If, on entering Verrières, the traveller asks who own that fine nail factory which deafens people who ascend the main street, someone will drawl in reply: Oh! That’s M. the Mayor’s. Stendhal, The Red and the Black There are three main doctrines enunciated by Flaubert: First, subject is not important. Second, the author must withdraw from his work, maintaining rigid objectivity and impassivity. Third, literature does not preach but shows. There is a fourth doctrine, that of making a beautiful work out of nothing, or as nearly nothing as possible. George G Becker, Documents of Modern Literary Realism, Princeton, (1963) What strikes me as beautiful, what I should like to do, is a book about nothing, a book without external attachments, which would hold together by itself through the internal force of its style….a book which would have practically no subject, or at least one in which the subject would be almost invisible, if that is possible. Flaubert, Letter to Louise Colet, January 16, 1852, cited in Becker (1963) Form: Style Indirect Libre and the Impersonal Author I think you can have no idea of the kind of book I am writing. In my other books I was slovenly; in this I am trying to be impeccable and to follow a geometrically straight line. No lyricism, no comments, the author’s personality absent. It will make dreary reading; it will contain atrocious things of misery and sordidness.’ Letter to Louise Colet, February 1, 1852, cited in Becker (1963) Madame Bovary contains nothing from life. It is a completely invented story. I have put into it nothing of my feelings, or of my experience. The illusion (if there is one) comes, on the contrary, from the impersonality of the work. It is one of my principles that you must not write yourself. The artist ought to be, like God in creation, invisible and omnipotent. He should be felt everywhere but not be seen. Flaubert, Letter cited in Becker (1963) Thanks to free indirect style, we see things through the character’s eyes and language but also through the author’s eyes and language, too. We inhabit omniscience and partiality at once. A gap opens up between author and character, and the bridge – which is free indirect style itself – between them simultaneously closes that gap and draws attention to its distance. This is merely another definition of dramatic irony: to see through a character’s eyes while being encouraged to see more than the character can see (an unreliability identical to the unreliable first-person narrator’s.) James Wood, How Fiction Works, p.10 MORE MISCELLANEOUS QUOTES…. At first glance, Madame Bovary can seem to be a commonplace story with a simple, unoriginal plot, featuring characters who are without exception, flawed or downright unpleasant […] this was all intentional on Flaubert’s part. Although he was himself, thoroughly bourgeois in his background and way of life, valuing comfort, stability, and wealth, he nevertheless detested bourgeois ways and bourgeois values […] besides this, it was Flaubert’s conscious intention to write an experimental novel, experimental not so much in its plot or characterisation as in its style and its handling of the details of everyday life; a novel, even, in which style was the essential quality, a work of art that was therefore largely concerned with itself. He laboured heavily over the language […] then, in describing dryly and realistically the facts and objects of daily life in a country town, he sought to transform the ordinary by bringing together its beauty and ugliness and finding aesthetic value in their combination […] This aspect of Flaubert’s style was revolutionary, showing up the unreality and melodramatic modes of other contemporary fiction; and it accorded perfectly with the subdued irony he displayed towards his characters, raising them from being merely ridiculous or despicable to being figures of pathos or tragedy. Phillip Gaskell (1999) Realism is no more than one kind of technique for selectively representing one way of looking at ‘reality’. It reacts against previous traditions that chose the fantastic, the idealistic or the exceptional, and sets out to create the illusion of observing impartially the ordinary events of average life. It need not logically imply insistence on the sordid, though in reacting against abstract and idealised presentations it may come to stress this side of things. Fairlie (1962) The hatred of realism is a hatred of the reality it represents […] The paradoxical force of Flaubert’s writing is then that realism, development and critique of romanticism, is itself equally subject to critique; the movement of disillusionment from romanticism to realism is also for him just as much a refusal of any of the illusions of the latter, of any of realism’s social, progressive purpose: realism is as execrable as the reality it knows and depicts, is caught in the surrounding stupidity, the general fetidness. Flaubert is the anti-realist at the heart of realism, with romanticism as the impetus and the edge of his critique, as the term for all the strength of desire negated by this bourgeois reality and by what is, for Flaubert, its realism. It is the distance from the given reality, exactly the execration of the ordinary life enacted in Emma’s story, that counts and that produces the lack of value for which the novel is brought to trial: romanticism has become demoralisation, remaining nevertheless as an aspiration in reaction against this world whose reality it seeks to expose, to set out as it really is, with no concessions to any of its fictions of itself […] For this duality of realism/romanticism, the very situation of his writing, Flaubert, then, has his resolution, a resolution by displacement to another value: Art. Reality is to be set out as it is, but also transformed, is to serve as a springboard for style, for the work of art. Those who most powerfully claimed Madame Bovary as a realist-naturalist model found themselves at the same time obliged to acknowledge that something did not quite fit […] Realism in Flaubert is platitude, the platitude of the reality and the platitude of this realism which is part of that reality: art alone can offer – can be – something else. Heath(1992) The concept of impersonality therefore, has nothing to do with the development of some third person voice, some voice of knowledge […] a sort of witness to things who guides our reading and decrees meanings, some supposedly –God-like narrator. God in Flaubert’s version is everywhere present but nowhere in particular, nowhere visible; impersonality, again, is immersion, circulation. It is not a question of an ‘objective’ position in the work but of a play of visions, perspectives, perceptions across the characters and their doings and their world, of a tissue of discourses, ideas, orderings of meaning; leaving the reader deprived of any given grounds as to ‘what to think’, not taken in hand by some privileged voice. Impersonality is accompanied by uncertainty; nothing is sure, nothing definitive. Flaubert’s truth is that there is no concluding truth other than the conclusion that there is no such truth, and art is true as the recognition of that; with impersonality as its mode of recognition, against the stupidity of conclusions. Heath (1992) To Flaubert himself the writer’s business is to create the illusion of life and leave the reader to draw his own conclusions. Fairlie (1962) I think we have a thirst for reality. Which is curious, since we have too much reality, more than we can bear. But that is the lived, experienced reality of the everyday. We thirst for a reality that we can see, hold up to inspection, understand. ‘Reality TV’ is a strange realization of this paradox: the totally banal become fascinating because offered as spectacle rather than experience – offered as what we sometimes call vicarious experience, living in and through the lives of others. That is perhaps the reality that we want. Peter Brooks, Realist Vision (2005) In Stendhal and Balzac we frequently and indeed almost constantly hear what the writer thinks of his characters and events; sometimes Balzac accompanies his narrative with a running commentary – emotional or ironic or ethical or historical or economic. We also very frequently hear what the characters themselves think and feel, and often in such a manner that, in the passage concerned, the writer identifies himself with the characters. Both these things are almost wholly absent from Flaubert’s world; His opinion of his characters and events remains unspoken; and when the characters express themselves it is never in such a manner that the writer identifies himself with their opinion, or seeks to make the reader identify himself with it. We hear the writer speak; but he expresses no opinion and makes no comment. His role is limited to selecting the events and translating them into language; and this is done in the conviction that one is able to express it purely and completely, more than any opinion or judgement appended to it could do. Upon this conviction – that is, upon a profound faith in the truth of language responsibly, candidly and carefully employed – Flaubert’s artistic practice rests. Auerbach (1953) Bibliography – There’s a huge amount of material on Realism, French Realism and Flaubert. This is just a selection. Feel free to explore other texts and resources. General Birkett, Jennifer, A guide to French literature: from early modern to postmodern (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1997) Finch, Alison, French Literature: A Cultural History (Cambridge: Polity, 2011) Gaskell, Phillip, Landmarks in European Literature (Edinburgh: EUP, 1999) Travers, Martin, An Introduction to Modern European Literature (London: Macmillan, 1998) General Realism Auerbach, Erich, Mimesis: the Representation of Reality in Western Literature (California: Princeton University Press, 1957) Becker, George J, Documents of Modern Literary Realism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1963) Ermath, Elizabeth Deeds, Realism and Consensus in the English Novel (1983) Furst, Lilian, Realism (London: Longman, 1992) Grant, Damian, Realism (Critical Idion) Kearns, Katherine, Nineteenth-century literary realism: through the looking glass (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996) Larkin, Maurice, Man and society in nineteenth-century realism: determinism and literature (London: Macmillan, 1977) McCabe, Colin, James Joyce and the Revolution of the Word (1979) Stern, JP, On Realism (1973) Tallis, Raymond, In Defence of Realism (1988) Tanner, Tony, Adultery in the novel: contract and transgression (NY: Johns Hopkins U.P., 1979) Turnell, Martin, The Rise of the French Novel (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1979) Williams, D. A. (ed), The monster in the mirror: studies in nineteenth-century realism (Oxford: Oxford U.P., 1978) On Flaubert Bloom, Harold (ed) Gustave Flaubert (NY: Chelsea, 1989) Curry, Biazzo, Description and meaning in three novels by Gustave Flaubert (New York: Peter Lang, 1997) Fairlie, Alison, Flaubert: Madame Bovary (London: E. Arnold, 1962) Fairlie, Alison, Imagination and language: collected essays on Constant, Baudelaire, Nerval, Flaubert (Cambridge: CUP, 1981) Heath, Stephen, Flaubert: Madame Bovary(Cambridge: CUP, 1992) Nadeau, Maurice, The Greatness of Flaubert (Manchester: Alcove Press, 1972 Porter, Lawrence (ed),Critical Essays on Gustave Flaubert (Boston: G K Hall, 1986) Roe, David, Gustave Flaubert (London: MacMillan, 1989) Schehr, Lawrence, Flaubert and sons: readings of Flaubert, Zola and Proust (New York: Peter Lang, 1986) Sherington, R. J. Three Novels by Flaubert (Oxford: OUP 1970) Starkie, Enid, Flaubert: the making of the master (NY: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1967) You might also want to check out sections on MB in Roland Barthes (1967) ‘The Reality Effect’ and Writing Degree Zero