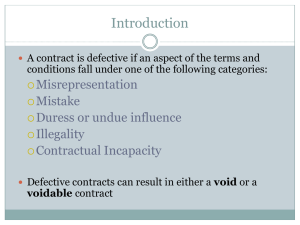

Contracts Law Summary: Remedies, Formation, Terms

advertisement