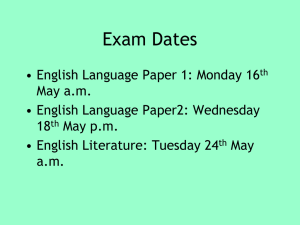

preparing for the exam

advertisement