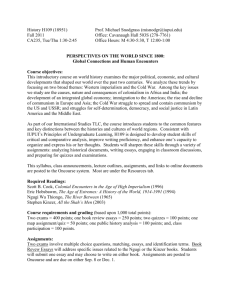

IGS 561a - WordPress.com

advertisement

IGS 561a: Directed Readings in Latin American and Iberian Studies: Cultural Exchange and Encounter in the Americas Winter Term I, Fall 2012 Mondays 6-8pm LIB 302 Jessica Stites Mor jessica.stites-mor@ubc.ca Blackboard: http://elearning.ubc.ca/connect/ This directed readings course will serve as an introduction to the field of social and cultural history of the Americas, with a special emphasis on encounter and exchange as a postcolonial theoretical approach to the period of 1492-1810. This course provides an overview of the scholarly literature and debates of Atlantic world historiography after European contact to the revolutions for independence on the eve of the national period. The course has four main thematic foci, of which each will be woven throughout the readings, the first is social history of contact and exchange, which will examine the experiences of American, European, and African men and women who formed the basis of colonial society in the Americas. As the course progresses, we will explore the ways in which the development of colonial governance regimes altered exchange and encounter, examining closely how institutions of keeping order expanded their influence and challenged existing patterns. We will then turn our attention to modes of cultural resistance and subaltern practices of challenging imperialism and the imposition of institutions of order. Finally, we will consider the intellectual exchange made possible by the trans-Atlantic traffic of the period. The course will conclude by examining each of these themes within the context of the Age of Revolutions, a period of dramatic upheaval that remains at the center of lively scholarly debates. Course objectives: -Students will be prepared in the general theory and historiography of the literature of the field. -Students will hone in their discussion, presentation, and argumentation skills, not only to demonstrate reading comprehension and analytical skills, but also to learn how to effectively engage in scholarly exchange. Evaluation: Discussion presentations 40% (Four discussions to lead per student of roughly 20 minutes each with additional Q and A, two on a main text, one on a supplemental text, and a third on a text related to the student’s own area of interest) Critical reflection papers x 6 60% (students choose weekly readings to respond to and circulate reflection papers in advance of meetings, papers should not exceed three pages of double-spaced text and should include bibliographic references and footnotes, due 24 hours before the start of class each week, to be posted on the class Blackboard and also hard copy handed in to professor, under office door) Readings by week: 1. Discovery, travel and encounter Peter Mancall and James Merrell, eds. American Encounters, Native Newcomers from European Contact to Indian Removal, 1500-1850, selected chapters. Edward Said, Orientalism Stuart Schwartz, ed, Implicit Understandings 2. Narratives of conquest Tzvetan Todorov, The Conquest of the Americas Inga Clendinnen, Ambivalent Conquests Matthew Restall, Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest Alfred Crosby, The Columbian Exchange 3. Autobiography and exploration Hans Staden, Hans Staden’s True History Cabeza de Vaca Captain Cook Bartolome de las Casas 4. Empire and ideology Anthony Padgen, Lords of all the World Canizares-Esguerra, Puritan Conquistadors Irene Silverblatt, Modern Inquisitions Paul Lovejoy, “The Yoruba Factor in the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade” The Yoruba Diaspora in the Atlantic World, Ed. Toyin Falola and Matt Childs, 40-55. Kenneth Mills, Idolatry and its Enemies 5. Science, gender, and race between continents Joyce Chaplin, Subject Matter Anne McClintock, Imperial Leather Susan Scott Parrish, American Curiosity Lorraine Daston and Katherine Park, Wonders and the Order of Nature 6. Exchange and possession Stephen Greenblatt, Marvelous Possessions Linda K. Heywood and John K. Thornton, “Privateering, Colonial Experience and the African Presence in Early Ango-Dutch Settlement”, Central Africans, pp. 5-48. Richard White, The Middle Ground. Mathew Restall, ed. Beyond Black and Red 7. Language, geography, and knowledge Walter Mignolo, Darker Side of the Renaissance James Lockhart, The Nahuas after the Conquest Kathryn Burns, Writing and Power in Colonial Peru Sabine MacCormack, On the Wings of Time 8. Belonging, identity, and exclusion John Demos, The Unredeemed Captive James Axtell, Natives and Newcomers Timothy Shannon, “Dressing for Success on the Mohawk Frontier,” American Encounters, pp. 533-560. James Axtell, “The White Indians of Colonial America” American Encounters, pp. 483-509. Natalie Zemon Davis, “Iriquois Women, European Women” American Encounters, pp. 84106. Gilles Paquet and Jean-Pierre Wallot, “Nouvelle-France/Québec/Canada: A World of Limited Idntities” Colonial Identities in the Atlantic World, 1500-1800, ed. Nicholas Canny and Anthony Padgen, pp. 95-114. 9. Cultures of resistance Christopher Fennell, Crossroads and Cosmologies Susan Deeds, “Subverting the Colonial Order” Choice, Persuasion and Coercion, Ed. De la Teja and Frank. 95-120. James Scott, Weapons of the Weak Sergio Serulnikov, Subverting Colonial Authority Robert Farris Thompson Flash of the Spirit 10. The Americas in European Thought Karen Ordhal Kupperman, ed. Americas in European Consciousness Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic Anthony Padgen, European Encounters with the New World 11. The problems and promise of settlement Ned Blackhawk, Violence over the Land Daniel K. Richter, “War and Culture: The Iroquois Experience”, American Encounters, pp. 427-454. James Scott, The Art of Not Being Governed Robert Hine and John Mack Faragher, Frontiers: A Short History of the American West 12. Negotiating governance Emilia Viotti da Costa, Crowns of Glory, Tears of Blood Richard White, “The Winning of the West”, American Encouters, pp. 685-704. John Farager, “More Motley than Mackinaw” American Encoutners, pp. 665-684. Tamar Herzog, Upholding Justice 13. Revolutionary Ideas Wim Klooster, Revolutions in the Atlantic World Laurent DuBois, Avengers of the New World John Lynch, The Spanish-American Revolutions David Armitage, "The Declaration of Independence and International Law," William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser., 59 (Jan. 2002): 39-64. Gordon Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution Academic Integrity. The academic enterprise is founded on honesty, civility, and integrity. As members of this enterprise, all students are expected to know, understand, and follow the codes of conduct regarding academic integrity. At the most basic level, this means submitting only original work done by you and -acknowledging all sources of information or ideas and attributing them to others as required. This also means you should not cheat, copy, or mislead others about what is your work. Violations of academic integrity (i.e., misconduct) lead to the break down of the academic enterprise, and therefore serious consequences arise and harsh sanctions are imposed. For example, incidences of plagiarism or cheating usually result in a failing grade or mark of zero on the assignment or in the course. Careful records are kept in order to monitor and prevent recidivism. A more detailed description of academic integrity, including the policies and procedures, may be found at http://web.ubc.ca/okanagan/faculties/resources/academicintegrity.html. Grading Scale: As this is a graduate course, the expected criteria for achieving marks in the course are as follows: 93-99 Exceptional ability, demonstrated mastery of the subject and consistently outstanding quality of work 85-92 Work meets expectations of a graduate student, consistently good performance and high quality of work 80-84 Work meets passing expectations, but could stand to be improved to meet expectations of a successful graduate student 68-79 Work does not meet expectations of a graduate student, this range is considered a “fail” and the student may be consulted about whether or not they should change status to auditor or request standing deferred. *Below 80 in graduate coursework results in student’s ineligibility for SSHRC and internal research and travel grants. **Below 68 and the student will likely not be able to continue in graduate studies at UBC Okanagan. History Writing and Argumentation: These are the key elements I will be looking for in judging and marking your written work and your presentations in class. -Understanding of language, specifically familiarity and ability to utilize terminology from readings and class discussion, ability to utilize conceptual language to describe historical events and processes. -Strong thesis statements, frequently these reflect a modest rather than a bold contribution that is well situated within a broader context of work on the subject. -Referentiality: ability to easily make use of relevant works of scholarship and theory, capacity to put them to use to refine and build arguments. -Organized, careful, economic prose; well-chosen evidence to substantiate claims. -Ability to evaluate primary evidence, determine its usefulness and any limitations, and think critically about how such evidence is presented and interpreted. -Creative expression, ability to communicate original ideas in a clear manner, without having to rely on hackneyed or common turns of phrase. -Voice, confidence in assertions, presence of a defined perspective, ability to take a position. -Relevance, communication of meaning or significance of the topic, ability to connect debates across temporal and spatial divides. -Concreteness, precision in discussion and argumentation, solid connections between evidence and argument, avoidance of vague language and passive voice, assigning causality and agency. -Insight, reflects consideration, analytical development; moves forward a position. -Curiosity, asks meaningful historical questions that have the potential to generate new perspectives and/or deep lines of inquiry. -Editing, use of proper citations, careful formatting; copy is clean. How to Lead and Participate Effectively in a Discussion Seminar: Discussion leaders will have roughly 20 minutes to present the work that they have chosen from the readings. It is a good idea to prepare a handout or an overhead presentation to help underline key points, but be careful not to rely on such materials, the key to success is the oral presentation itself. For Discussion Leaders: The discussion should cover the following key items: 1. An introduction to the reading and topic: Who wrote the piece? What is their particular approach? What arguments are they responding to within their field? 2. Overview of the argument: Discuss author's main conclusions or positions, methodology, theoretical approach, sources. 3. Present your view: This is not just a matter of telling the group "how you feel" about these things, but rather, what kind of reasonable response you can give. Address the argument itself, the sources, the relationship between the reading and the body of work to which it responds. 4. Raise good questions: Spark discussion among peers by raising a set of significant questions. Question to open discussion, clarify and expand knowledge: Good discussion questions are not answered by "yes" or "no." Instead they lead to higher order thinking (analysis, synthesis, comparison, evaluation) about the work and the issues it raises. Good questions recognize that readers will have different perspectives and interpretations and such questions attempt to engage readers in dialogue with each other. Such questions depend on a careful reading of the text. Good discussion questions are simply and clearly stated. They do not need to be repeated or reworded to be understood or rely too heavily on jargon. Good discussion questions make (and challenge) connections between the text at issue and other works, and the themes and issues of the course. Ask small, detailed questions (like "what's the argument for this conclusion?") before large, abstract questions (like "how does this compare with what so-and-so said?"). Ask interpretative questions (like "what does the author mean here?") before evaluative questions (like "is the author right about this?"). Let your earlier questions lay a foundation for your later questions. Be flexible about your list of questions. If the discussion is going well, go with the flow, but always be ready to bring it back into line when it wanders away from the discipline, or becomes pointless. For Seminar Members: Successful discussion relies on your participation and preparation. 1. DO THE READING IN ADVANCE - this is absolutely essential for a seminar to work. You cannot rely on the presenter to explain things - there will be no discussion then, just a dry monologue. That's not a seminar. 2. Listen actively – What are the main contributions that the presenter has made to interpreting or understanding the text? Think about whether you think the presenter is getting the reading right. Is he/she missing some central issue? Has he/she not quite understood the argument? Are there implications of the argument that the presenter is not bringing to the surface? 3. Bring relevant outside material to the attention of the group, when appropriate. 4. Answer questions when you can, even if you can’t, try to respond in some way as to move forward the discussion. Listen to Record, Reflect and Respond: Listening is an essential skill and an important element of any discussion. Effective listeners don't just hear what is being said, they think about it and actively process it. • Be an active listener and don't let your attention drift. Stay attentive and focus on what is being said. • Identify the main ideas being discussed. • Evaluate what is being said. Think about how it relates to the main idea/ theme of the tutorial discussion. • Listen with an open mind and be receptive to new ideas and points of view. Think about how they fit in with what you have already learnt. • Test your understanding. Mentally paraphrase what other speakers say. • Ask yourself questions as you listen. Take notes during class about things to which you could respond. Discussion Etiquette: In order to successfully conduct and participate in a discussion, courtesy and respect are the basic ground rules. Do • Respect the contribution of others. Speak with courtesy to all members of the group. • Listen well to the ideas of other speakers; your response will be more informed if you pay attention to the points that they make. • Acknowledge what you find interesting. Particularly if it represents a different point of view. • Refrain from being argumentative. Learn to disagree politely. • Think about your contribution before you speak. How best can you answer the question contribute to the topic? • Try to stick to the discussion topic. Don't introduce irrelevant information. If the discussion does digress, bring it back on topic by saying something like 'Just a final point about the last topic before we move on' or 'that's an interesting point, can we come back to that later? Don't • Don't take offence if another speaker disagrees with you. Putting forward different points of view is an important part of any discussion. Others may disagree with your ideas, and they are entitled to do so. • Never try to intimidate or insult another speaker or ridicule the contribution of others. • Don’t dominate the discussion. Confident speakers should pause to allow quieter students a chance to contribute. • Avoid drawing too much on personal experience or anecdote. Although personal experiences can be helpful, remember not to generalize and to stay on point. • Don't interrupt or talk over another speaker. Let them finish their point before you start.