Enclosure+k

advertisement

SCFI 2011

Enclosure K (Space Daesins)

Silent Nihilists.

___ of ___

Index

Index .............................................................................................................................................................. 1

Crusoe Syndrome 1NC.................................................................................................................................. 2

Link: Militarization ........................................................................................................................................ 10

Link: Get off the rock.................................................................................................................................... 11

Link: Econ .................................................................................................................................................... 13

Link: Infinite Resources ............................................................................................................................... 14

Links- exploration ........................................................................................................................................ 15

Link: Colonizing ........................................................................................................................................... 17

Link: GPS/Positioning .................................................................................................................................. 18

Link- Resources........................................................................................................................................... 23

Link- Satellites ............................................................................................................................................. 24

Link: development = commercial use .......................................................................................................... 27

Link: Treaties ............................................................................................................................................... 29

Link: Mars .................................................................................................................................................... 30

Link: Mars (Zubrin specific).......................................................................................................................... 31

Impact: Genocide ........................................................................................................................................ 32

Impacts- Standing reserve ........................................................................................................................... 34

Impacts- Genocide....................................................................................................................................... 36

Impact- destruction of the commons ............................................................................................................ 37

Alt Solvency ................................................................................................................................................. 38

Case turn: Econ ........................................................................................................................................... 40

A2: Perm...................................................................................................................................................... 41

A2: Timeframe ............................................................................................................................................. 43

A2: Science first ........................................................................................................................................... 44

A2: Alt does nothing..................................................................................................................................... 45

Ethics first (Also A2 Perm) ........................................................................................................................... 47

Value to life O/W Extinction ......................................................................................................................... 49

Reps first ..................................................................................................................................................... 50

***AFF answers: commons turn ................................................................................................................... 52

AFF Answers: Onto bad .............................................................................................................................. 53

AFF answers: tech inevitable ....................................................................................................................... 54

AFF answers: Perm ..................................................................................................................................... 55

AFF answers: Alt fails .................................................................................................................................. 57

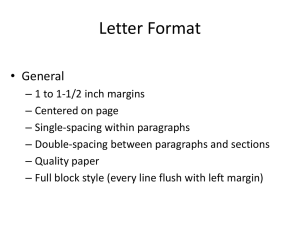

To update index - Right click and select “UPDATE FIELD”

I am going to beat you with my baby bump.

1

SCFI 2011

Enclosure K (Space Daesins)

Silent Nihilists.

___ of ___

1NC (normal)

A) The 1AC inducts space into the open market- ready to be sold to the highest

bidder for its resources; where one sees an open commons corporate entrepreneurs

always see a new way to make money

Bollier ‘4 (Space as the final frontier of the Commons; David Bollier [activist and writer about the commons]; June 23, 2004;

http://onthecommons.org/space-final-frontier)

Space is apparently the “final frontier” for the free market. If most of us look up at the heavens in wonder, a scheming

corps of entrepreneurs are apparently seeing space and celestial bodies (planets, asteroids, solar energy) for their raw market

value…especially now that a private rocket has been successfully launched. Peter Montague alerted me to a recent essay by Bruce

Gagnon of the Global Network Against Weapons & Nuclear Power in Space, who writes about the coming privatization of space. One problem is the growing

“pollution” of space by orbiting trash; more than 100,000 identifiable bits of debris are monitored by NORAD. Another problem is what “law” shall govern claims to

“property” in space. The

U.S. refused to sign a United Nations “moon treaty” in 1979 lest it preclude military uses of the moon

and space. But the treaty, writes Gagnon, also outlaws any “ownership” claims on the moon. Gagnon writes: “As the privateers

move into space, in addition to building space hotels and the like, they also want to claim ownership of the planets

because they hope to mine the sky. Gold has been discovered on asteroids, helium-3 on the moon, and magnesium,

cobalt and uranium on Mars. It was recently reported that the Haliburton Corporation is now working with NASA to develop new drilling capabilities to

mine Mars.” A group called United Societies in Space (USIS) sees space as the “free market frontier,” and wants to

encourage private property rights and investment in space. Once again the same dynamic repeats itself: taxpayers spend billions upon

billions of dollars to develop a new technology or resource, and then the “private sector” (sic) marches in to privatize the profits.

B) Plan means that space will be privatized, falling prey to the same managerial

control that wrecked the earth environment

Collis & Graham 2009. (Institute for Creative Industries and Innovation Professor of Communication and Culture

Queensland University of Technology.) Political Geographies of Mars: A history of Martian management. Management and Organisation History, 4(3).

http://eprints.qut.edu.au/21225

The general assumption of corporate lobbying in relation to Space law is that the future of Space is a corporate future, that Space

business entails significant risk, and that therefore, it is important that ‘the best course of action is for the spacefaring nations to enact legislation which provides

for property rights without territorial sovereignty’ (White 2009 cited in 4Frontiers Corporation 2009b). Along with 4Frontiers, corporate and government

agencies have turned their interests to mining the cosmos (see for instance Lucidian 2008–2009; Valentine 2002). Often such efforts

are framed by a concern for the environment (O’Neill 2000). In the tradition of managerial ‘technocratic discourse’ (McKenna

and Graham 2000), the threat of a catastrophic future is put forward as a reason for more of the same, and for why Space

cannot be profitably seen as terra communis. Valentine (2002), Director of the Space Studies Institute, exhorts the private sector to ‘mine the

sky, defend the Earth, [and] settle the Universe’. Free market managerialism naturally sees the private sector as central to such

efforts and, clearly, the terra communis view of Space is due an enclosures movement of its own, first in discourse

then in commercial and technical practice.

I am going to beat you with my baby bump.

2

SCFI 2011

Enclosure K (Space Daesins)

Silent Nihilists.

___ of ___

1NC (Normal)

C) The affirmative results in a standing reserve which calculates, controls, and

obliterates any value to life and the environment

Mitchell 5 [Andrew J. Mitchell, Post-Doctoral Fellow in the Humanities at StanfordUniversity, "Heidegger and Terrorism," Research in Phenomenology,

Volume 35, Number 1, 2005 , pp. 181-218]/

Opposition is no longer an operative concept for Heidegger, since technology has served to eradicate the distance that would separate the supposedly opposed

parties. The analysis of technology in Heidegger's work is guided by the (phenomenological) insight that "All distances in time and space are shrinking" (GA 79:

3; cf. GA 7: 157/PLT, 165).13Airplanes, microwaves, e-mail, these serve to abbreviate the world, to be sure, but there is a

metaphysical distance that has likewise been reduced, that between subject and object. This modern dualism has been

surpassed by what Heidegger terms the standing-reserve(Bestand), the eerie companion of technological dominance and "enframing." Insofar as an

object (Gegenstand) would stand over against (Gegen) a subject, objects can no longer be found. "What stands by in the sense of standingreserve, no longer stands over against us as object" (GA 7: 20/QCT, 17). A present object could stand over against another;

the standing-reserve, however, precisely does not stand; instead, it circulates, and in this circulation it eludes the

modern determination of thinghood. It is simply not present to be cast as a thing. With enframing, which names the dominance of

position, positing, and posing (stellen) in all of its modes, things are no longer what they were. Everything becomes an item for ordering

(bestellen) and delivering (zustellen); everything is "ready in place" (auf der StellezurStelle), constantly available and replaceable (GA

79: 28). The standing-reserve "exists" within this cycle of order and delivery, exchange and replacement. This is not

merely a development external to modem objects, but a change in their being. The standing-reserve is found only in its

circulation along these supply channels, where one item is just as good as any other, where, in fact, one item is identical to

any other. Replaceability is the being of things today. "Today being is being-rephlceable"(VS, 107/62), Heidegger claims in

1969. The transformation is such that what is here now is not really here now, since there is an item identical to it somewhere else ready for delivery. This cycle

of ordering and delivery does not operate serially, since we are no longer dealing with discrete, individual objects. Instead,there

is only a steady

circulation of the standing-reserve, which is here now just as much as it is there in storage. The standing-reserve

spreads itself throughout the entirety of its' replacement cycle, without being fully present at any point along the

circuit. But it is not merely a matter of mass produced products being replaceable. To complete Heidegger's view of the enframed standing reserve, we

have to take into consideration the global role of value, a complementary determination of being: "Being has become value"

(GA 5: 258/192). The Nietzschean legacy for the era of technology (Nietzsche as a thinker of values) is evident here. But the preponderance of value is so far

from preserving differences and establishing order of rank, that it only serves to further level the ranks and establish the identity of everything with its

replacement. When everything

has a value, an exchangeability and replaceability operates laterally across continents,

languages, and difference, with great homogenizing and globalizing effect. The standing-reserve collapses

opposition. The will that dominates the modem era is personal, even if, as is the case with Leibniz, the ends of that will are not completely known by the self

at any particular time. Nonetheless, the will still expresses the individuality of the person and one's perspective. In the era of technology, the will that comes to

the fore is no longer the will of an individual, but a will without a restricted human agenda. In fact, the will in question no longer wills an object outside of itself, but

only wills itself; it is a will to will. In this way, the will need never leave itself. This self-affirming character of the will allows the will an independence from the

human. Manifest in the very workings of technology is a will to power, which for Heidegger is always a will to will. Because the will to will has no goal outside of it,

its willing is goalless and endless.The human is just another piece of a standing-reserve that circulates without purpose. Actually,

things have not yet gone so far; the human still retains a distinction, however illusive, as "the most important raw material" (GA 7: 88/EP, 104). This importance

has nothing to do with the personal willing of conditional goals, as Heidegger immediately makes clear,"The human is the 'most important raw material' because

he remains the subject of all consumption, so much so that he lets his will go forth unconditionally in this process and simultaneously becomes the 'object' of the

abandonment of being" (GA 7: 88/EP, 104). Unconditioned willing transcends the merely human will, which satisfies itself with restricted goals and

accomplishments. Unconditioned willing makes of the subject an agent of the abandonment of being, one whose task it is to objectify everything. The more the

world comes to stand at the will's disposal, the more that being retreats from it. The human will is allied with the technological will to will. For this reason-and the

following is something often overlooked in considering Heidegger's political position between the wars-Heidegger is critical of the very notion of aFR'hrer, or

leader, who would direct the circulation of the standing-reserve according to his own personal will. The leaders of today are merely the

necessary accompaniment of a standing-reserve that, in its abstraction, is susceptible to planning. The leaders'

seeming position of "subjectivity," that they are the ones who decide, is again another working of "objectification,"

where neither of these terms quite fits, given that beings are no longer objective. The willfulness of the leaders is not due to a

personal will: One believes that the leaders had presumed everything of their own accord in the blind rage of a selfish egotism and arranged everything in

accordance with their own will [Eigensinn]. In truth, however, leaders are the necessary consequence of the fact that beings have gone over to a way of errancy,

in which an emptiness expands that requires a single ordering and securing of beings. (GA 7: 89/EP, 105; tin) The leaders do not stand above or control the

proceedings, the proceedings in question affect beings as a whole, including the leaders. Leaders are simply points of convergence or conduits for the channels

of circulation; they are needed for circulation, but are nowhere outside of it. No leader is the sole authority; instead, there are numerous "sectors" to which each

leader is assigned. The demands of these sectors will be similar of course, organized around efficiency and productivity in distribution and circulation. In

short,leaders

serve the standing-reserve.

I am going to beat you with my baby bump.

3

SCFI 2011

Enclosure K (Space Daesins)

Silent Nihilists.

___ of ___

1NC (Normal)

D) Alternative: Reject the 1AC’s enclosure of space.

By shifting our paradigm from one of commodification to one which values the

commons we perform a mental excavation allowing for real change to occur

Ristau and Bradley 10 http://onthecommons.org/commons-meets-community; May 14, 2010; Julie Ristau and Alexa Bradley (community organizers.

Ristau is Managing Fellow of On The Commons and Bradley is Associate Director of the Grassroots Policy Project)

From many of us who lived in the communist world, waiting was often, if not always, close to an outer limit.

Surrounded, enclosed, colonized from within by the totalitarian system, individuals lost any expectation of finding a

way out. In a word, they lost hope. Yet they did not lose the need to hope, nor could they lose it, for without hope life

loses its meaning. ??“Playwright, philosopher, and politician Vacel Havel. Imagine what would happen if the commons paradigm

became the fundamental orientation for our lives. It requires a break in habitual thinking. A jolt. A leap. We step

through the looking glass. We look back at the earth from the moon. We cross over. Paradigm shifting. It will take some

imagination. It will take some excavation of memory and feeling. Working on the commons is in part, about cracking

open the constraints on our imaginations that keep us from even seeking a transformed reality. The commons has

power in the way that it has both a material basis and a history??“there are and have been many commons which people have observed

and benefited from??“and there is an idea of commons that has existed and evolved over time. We have found that people can identify

commons experiences in their own life , as well as the history of their families, communities and country. A commons

is an imaginable if largely forgotten reality, not just a theoretical idea. What reawakens our ability to think from the

perspective of a commons paradigm? We wonder, what is the role of memory in imagination and hope? Memory could

play a central character in the “naming” aspect of our work. When we exchange memories, even when we silently remember or

write down something from our past, then we notice that memory puts together the experiences which have been stored in our

mind in a new manner. Memory does not just recall, but rather it is a creative process, it builds new connections. It works

associatively, narratively like poetry. It is a matter of putting together the story anew. And in this form of remembering,

something very important happens: it’s not that we can return to the past, but rather we appropriate it, we recover

and use it for our present day life in a manner which is useful to us and our relationships with one another. We have been

focused on significance and meaning in the naming part of our workshop. The question we follow up with after we have named (what is one commons you can

think of) is one about meaning, when perhaps we should be more dwelling.

I am going to beat you with my baby bump.

4

SCFI 2011

Enclosure K (Space Daesins)

Silent Nihilists.

___ of ___

Crusoe Syndrome 1NC

A) Humans fear the unknown and thus attempt to control it. This is “Crusoe

Syndrome” -the ideology which encloses space so we can feel as if we are “in

control” when in fact we are in a state of chaotic relation to the unknown. This

paradox forces us to continually use space as a means to destroy it

Marzec 2002 (Robert P. Associate Professor at the State University of New York at Fredonia, “A Genealogy of Land in a Global Context,” boundary 2,

Volume 29, Number 2, Summer 2002, pp. 129-156 (Article), MUSE, JR2)

When Robinson Crusoe first sees the island that will eventually become his homeland for twenty-seven years, he is

so filled with anxiety that he codes the land as ‘‘more frightful than the Sea.’’1 Fearful of unknown space, he spends

his first night inhabiting the land not on its own terms but metaphysically above it in a tree (RC, 36).2 Uncontrollably

thrown into the space of uncultivated land, he is unable to immediately establish a frame of reference, which triggers

a response of dread: The land appears as an example of the Lacanian Real, a nonsymbolizable, meaningless

presence that bewilders Crusoe’s sensibility, and by extension the sociosymbolic order of the British Empire that he

carries on his back.3He broods over the potential for ‘‘God to spread a table in the Wilderness’’ (RC, 69, 107) and

gradually eases his dread by spending decades setting up a series of enclosures that slowly cover the landscape. It

is not only Crusoe who fears uncultivated land and achieves order by enclosing it; Daniel Defoe himself was a great

believer in the power of enclosures to establish a radically new mode of enlightened (imperial) existence that

transformed the land into an object to be mastered by humankind. In A Tour through the Whole Island of Great Britain, Defoe

surveys the domain of England’s immediate landscape, cataloging in some six hundred pages every quarter of

English soil. Throughout, he advocates the scientific and market-driven normalization of the land, valorizing enclosures

as ‘‘islands of improvement in a sea of open-field.’’4 In the fictional (but more widely read and thus more culturally significant) Robinson

Crusoe, this same enclosing of the land authorizes Crusoe to spread God’s table and allows him to climb down from

the tree (yet ‘‘remain’’ there in a metaphysical sense) to occupy the space of the Other. Only from within the pale of enclosures

does Crusoe establish a relation to the land, a relation that is at the same time paradoxically not of the land, for the land

must become English land before he can connect to it in any substantial fashion. After God’s table is spread, Crusoe says that he no longer

‘‘afflict[s] [his] self with Fruitless Wishes of being there,’’ for the island has come to radiate with the ‘‘Dispositions of

Providence,’’ which ‘‘quiet his Mind’’ and ‘‘order every Thing for the best’’ (RC, 79–80; my emphasis). Crusoe tames

the undifferentiated earth of the island by endowing the land with the positive and moral ‘‘seed’’ of ‘‘Providence.’’ In

order to cope with an entirely Other form of land than that to which he is accustomed, he introduces an ideological

apparatus to overcode the earth. In this fashion, he can ‘‘quiet’’ his mind, relieve his anxiety, and resist the nightmare

of actually ‘‘being there’’ on the island: the terror of inhabiting an Other space as Other. This ‘‘being in the tree,’’ a

resistance to ‘‘being there’’ until the land is enclosed and transformed, is the structure of what I call the Crusoe

syndrome.

I am going to beat you with my baby bump.

5

SCFI 2011

Enclosure K (Space Daesins)

Silent Nihilists.

___ of ___

B) Imperialism shines true, the plan is the next novel of unexplored space attempting

to redefine “the commons of space” as dangerous but controllable. this allows us to

not only colonize it, but also to deem any part of space that is not economically up to

“par” with other parts as savage, unknown and dangerous—that’s an independent

link to imperialism and ongoing genocide

Marzec 2002 (Robert P. Associate Professor at the State University of New York at Fredonia, “A Genealogy of Land in a Global Context,” boundary 2,

Volume 29, Number 2, Summer 2002, pp. 129-156 (Article), MUSE, JR2)

Defoe’s handling of the land in his Tour and in Robinson Crusoe indicates, I claim, a more global structure of feeling

coming into existence during this preimperial historical occasion. It is a structure that stands as a formal diagram for

future colonial developments: Before England began to colonize open, wild, and uncultivated land and subjects

abroad, it created an apparatus for colonizing its open land and subjects at home—an apparatus that could readily be

transplanted to distant territories.5Enabling the British subject to establish a sovereign sense of identity, enclosures precipitate and prepare the way

for England’s relocation in the expanding circle of the colonial world map. It was in the enclosure act that the ideology of imperialism

became a material reality, with enclosures creating a new problematic that formed a nexus between the growing

colonial cultural order, the domestication of foreign lands and peoples, monopoly capital, and the novel. English novels from the

eighteenth to the twentieth century contain a surprising number of significant references to enclosures and to the chaotic nature of unenclosed savage common

lands. These references indicate the extent to which the

English novel itself is inscribed in the midst of a new imperial formation of

land. Throughout Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones, for example, Jones receives repeated warnings and punishments for transgress5. The British colonization of

America certainly predates Defoe’s novel. However, the enclosure movement itself (before the specifically ‘‘parliamentary’’ enclosure waves of the

eighteenth century) was well under way by the beginning of the seventeenth century, and the first enclosures date from the dissolution of the monasteries.

transgressing enclosed borders.6Before the truth of Jones’s blood relation to Allworthy is discovered, Jones cannot claim a legal and moral connection to the

land. He lives as a vagabond, without any right to English soil and, consequently, any legitimized form of identity. Escaping his label as a vagabond to eventually

become a legal landowner is synecdochic of a narrative imperative that buttresses the classical novel form: The novel’s hero reaches his or her maturation by

domesticating itinerant (false) tendencies. By connecting identity maturation to gaining a legal and moral right to the land,

Fielding replicates Defoe’s narrative and the development of Crusoe from a wayward traveler who has no identity to a

landowning governor. This relation between identity and the land appears repeatedly in the form of an anxiety that

overwhelms the (pre)imperial subject, an impatience marked by a certain nonfoundational nomadic movement that

must eventually be tamed and managed by being inserted into a colonial system of utility. Robinson Crusoe, in the early

stages of his identity formation, feels compelled time and again to escape from national borders by going to sea,

even at the risk of his own death. What becomes transparent is a nonsubjective ontological flow of desire, an irreducible

and founding concomitant of the act of constituting an imperial subjectivity. The colonialist/imperial opposition between a self who is

governed by an unruly nomadic impulse and one who has domesticated this impulse by becoming an agriculturalist

(settler) is a structural imperative of Western teleological narratives of identity formation: The movement of nomadic

desire must come under control through the commodification of that desire in a colonialist apparatus. The specific

form of that commodification is the enclosure act—the grounding of a previously open subjectivity in a fabricated

(colonized) land. Symptoms of this fear of uncolonized desire/land surface in other novels. Samuel Richardson’s Pamela states at one point that she

would go so far as to suffer the terrors of being stranded on some ‘‘wild common’’ rather than stay in confinement

with Mr. B. Yet when a chance to escape arises, she recoils from crossing this anarchic territory. In Tobias Smollet’s

Humphrey Clinker, Matthew Bramble travels extensively through England, Assiduously tallying the financial success and the‘‘civility’’of

those who have cultivated enclosures out of ‘‘uninhabitable’’ fields ‘‘lying [in] waste.’’ At the end of the novel, Bramble proudly

proclaims that everything within his field of vision has reached the point of being regulated to his satisfaction: The fields have been ‘‘improved,’’ the

economy of the farms are being ‘‘superintended,’’ and the general cultivation of enclosed country life gradually finds

the characters ‘‘perfectly at ease in both . . . mind and body.’’7In Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, the unenclosed

commons appear as a region of delinquency, an influence leading to a lack of mental discipline, to a ‘‘loitering’’ and

wild mind.8E.P.Thompson has shown that signifiers such as wild, barbarian, and wicked came to be part of one’s

daily vocabulary when referencing those who lived on the commons.9George Eliot deploys a similar metaphorics of enclosure in her

novels. In Adam Bede, the wealthy landowner Arthur Donnithorne dreams of applying the enclosing techniques of the famous agriculturalist Arthur Young. In

this manner, he can discipline himself and tame the ‘‘wild country’’ but also discipline his farmers to ‘‘a better

management of the land,’’ whereby he may ‘‘overlook’’ them from atop his horse.10In Charlotte Brontë’s Shirley, Robert Moore

triumphs as the hero at the end of the novel, in part because of his promise to reterritorialize the landscape by securing an act to

I am going to beat you with my baby bump.

6

SCFI 2011

Enclosure K (Space Daesins)

Silent Nihilists.

___ of ___

enclose the open space of Nunnely Common. With an act of enclosure, the tensions of the novel disappear;

everything finds its ‘‘proper’’ place at the conclusion: Moore doubles the value of his mill property, expands his

manufacture and holdings, turns ‘‘wild ravines’’ into ‘‘smooth descents,’’ remakes the ‘‘rough pebbled track’’ into an

‘‘even, firm, broad, black, sooty road,’’ and parcels out the entire parish between himself and his brother.

C) The alternative is to re-imagine space as a place of utter chaos with out any sense

of dictation that allows us to truly realize the imperial ontology that creates the

unknown as an adversary for freedom and an enemy of the Rhizome

Spanos in 2009 (Willam V.Distinguished Professor of English and comparative literature at Binghamton University, “Disclosing Enclosure,” symploke,

Volume 17, Numbers 1-2, 2009, pp. 307-315 (Review), MUSE, JR2)

Following his genealogical examination of these early, canon-forming British novels that focus primarily on the way the

enclosure of the open land of

the Commons inaugurates the self as “free” individual and the nation as a unified space of privatized of property,

Marzec goes on to analyze a number of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century British novels that in increasing degree point both 1) to the fulfillment

of the logical economy of land enclosure in the establishment of the global enclosure movement that has come to be

called imperialism and 2) to its demise: the dis-closure in the very moment of arriving at its logical end (its closure) of

that ineffable (unrepresentable) force of being that this disciplinary logic of enclosure, which see it as “lack,” cannot

finally contain. In so doing, they also announce 3) an alternative—an-archic, non-representational—understanding of

the land, that is, the positive onto-eco-political possibilities inhering in precisely what the truth discourse of enclosure

demonized: the nothing, the earth, openness, agonic relationality (between human beings and the land), instability,

singularity, errancy, nomadic flow, the commons, and so forth. In the process, not incidentally, Marzec shows how

blinded to the crucial ontological register the canonical and even avant-garde commentators on these modernist

novels have been by their unexamined adherence to the very visualist/disciplinary perspective (the view from

above—what Althuser would call their capitalist “problematic”—that compartmentalizes being into (spatial) tables

(and disciplines) that constructed—and naturalized—the individual self, the nation as space of private property, and

the imperial world view. “The conclusions drawn from these liberal humanist approaches…to the question of finding a

‘truer’ relation to one’s territory,’’ Marzec writes, “all fail to break free from the economy of agricentrism, which can be

seen at play in the very terms deployed by these critics in the struggle to gain freedom: ‘middle ground,’ ‘unity,’ ‘organic

essence,’ ‘landscape,’ ‘order,’ ‘balance,’ ‘equilibrium,’ and so on.” As a result, this “search for a ‘truer’ relation based on an organically

inherent equilibrium occludes the resistant character of the land, and passes by the possibility of thinking humanity’s

proximity to the land from the dynamic of an exchange-limit structure” that wards off the apparatuses of capture

(126). Once this regulative logic of enclosure has been thematized, in other words, Marzec’s book goes on to infer an alternative

postcolonial strategy that thinks the alienation of the subject produced by the dynamics of enclosure primarily in terms Heidegger’s

essays on the relation between earth and world (the essays “The Question Concerning Technology,” “The Origins of the Work of Art,” “Building Dwelling,

Thinking,” for example ) and, above 312 all, Deleuze and Guattari’s “Treatise on Nomadology,” in their great book Milles plateaux (1980). This “nomadology,”

Marzec claims in the

process of a lucid and illuminating earlier reading of this difficult text, enables a return to the

(non)foundational imperatives that endows human being with an identityless self that relates to the resistant earth in

the form of the rhizomatic inhabitancy that the individuating and alienating logic of enclosure has disabled. Marzec

inaugurates this turn toward the question of a people’s integral/rhizomatic relation to the land and to the potential

resistance to acts of enclosure and colonization by way of extremely original deconstructive readings of Thomas Hardy’s

Return of the Native (1878), D. H. Lawrence’s The Rainbow (1915), and, above all, E. M. Forster’s Howard’s End (1910) and A Passage to India (1924): the

fiction that the fulfillment of the “benign” logic of both domestic and global enclosure has compelled it to address by

way of disclosing at this end its predatory essence. All of these novels published in the interregnum between the

colonial and postcolonial ages, each in their own degree and way, disclose what the dominant and polyvalent

discourse of enclosure represent as “lack” (negatively) to be a positive “warding off”: the finally unaccommodatable

spectral force that haunts the structuralist discourse of enclosure that would transform “it” into “meaning.” I cite, for

economy, an exemplary passage from Marzec’s originary reading of E. M. Forster’s Howard’s End and A Passage to

India, in which Forster pits the Hindu professor, Godbole’s non-presentational language, attuned to the earth’s

resistance to classified and fixed, against his English interrogators’ anxious will, grounded ultimately in the logic of

enclosure, to name the ineffable Marabar caves: As the conversation unfolds, each of the characters attempts to nail

down the correct description of the caves. They each attempt to name the precise nature of the caves, to unearth

their meaning. Godbole, however, is carrying on a different kind of communicatory act, which the others do not hear.

I am going to beat you with my baby bump.

7

SCFI 2011

Enclosure K (Space Daesins)

Silent Nihilists.

___ of ___

The caves appear in a tendential emergence that cannot be traced. They are not an object to be given over to

mastery, but an opening that the characters cannot assail. And they cannot assail it for the very reason that they all

take the approach of “discovery.” It is, in fact, exactly the imperial logic of discovery that the novel travesties in this

passage. The conversation begins to exert pressure on the characters’ need to know, their need to explore, and

stake a claim for understanding. It is this same kind of withholding of positive knowledge that we see performed as well in the character of Ruth

Wilcox [in Howard’s End],who, when she is coerced by Margaret into giving a precise answer [in an earlier conversation], move’s “with uneasiness beneath the

clothes.” (147)

I am going to beat you with my baby bump.

8

SCFI 2011

Enclosure K (Space Daesins)

Silent Nihilists.

___ of ___

I am going to beat you with my baby bump.

9

SCFI 2011

Enclosure K (Space Daesins)

Silent Nihilists.

___ of ___

Link: Militarization

The militarization of space is an expansion of American imperialism which seeks to

privatize and commodify resources

Dickens and Ormrod 7 - *Peter, Affiliated Lecturer in the Faculty of Social and Political Sciences at the University of Cambridge and Visiting

Professor of Sociology, University of Essex and **James, Lecturer in Sociology at the University of Brighton

(Cosmic Society: Towards a sociology of the universe, pg 94-95,

The United States government is by far the dominant military force in outer space. And its aim in militarizing outer

space is to achieve what the US Joint Chiefs of Staff call ‘full-spectrum domination’, one in which the US government actively

enforces a monopoly over outer space as well as air, land and sea. The purpose of this monopoly is not simply to

control the use of force on Earth, but also to secure economic interests actually in space, present and future. As we go

on to argue in Chapter 4, satellites have become so crucial to the functioning of the world economy that there has been

increasing tension amongst the cosmic superpowers over their vulnerability to attack, either from Earth-based

weapons or from weapons mounted on other satellites. Star wars systems are conceived in part to protect space

assets from perceived threats. If more people are going to be encouraged to invest in space technology, they will need guarantees from their

governments that their investments will be protected. The US has historically been anxious about other nations attempting to control Earth orbit, and for that

reason an American Space Station was proposed, one that would ensure that access to space was vetoed by American interests. Fortunately, the US decided,

perhaps historically rather surprisingly, that in the post-Cold War climate cooperation with other countries in the project would be more beneficial than a unilateral

solution, and so the American Space Station became the International Space Station. In 1989 a congressional study, Military Space Forces: The Next 50 Years

(Collins 1989), argued along similar lines that whoever held the Moon would control access to space. This echoed an older 1959 study, and appears to be a

possible motive for the recent initiative to establish an inhabited Moon base by 2024. With a system of property rights already being drawn up for space

resources, a military presence in space to ensure these rights is becoming an increasing priority. Historically, as many

pro-space advocates point out, colonization has been established through the military. Pro-space activists have generally been

divided over the issue of weapons in space (Michaud 1986). There are those who are against it per se, but even fewer see it as a positive use of space. There

are, however, some who see it as a necessary evil in order to protect space assets and operations, and as a possible step in the eventual settlement of space.

analysis of the new form of imperialism is again useful in understanding these military developments. It is

unlike that typically pursued until the late nineteenth century. It does not entail one society invading another with a

view to permanently occupying that society and using its resources. Rather, it entails societies (and particularly the

US with its enormous fusion of capital and political power) privatizing and commodifying resources previously owned

by the public sector or held in common in other ways. This process is developing within the ‘advanced’ societies,

such as the US. But, even more important, it is a strategy that is being spread throughout the cosmos.

Harvey’s

I am going to beat you with my baby bump.

10

SCFI 2011

Enclosure K (Space Daesins)

Silent Nihilists.

___ of ___

Link: Get off the rock

Getting off the rock is a band-aid solution. The earthly problems that put us at this

point will simply replicate themselves

Lin, 06. Patrick, Assistant Professor at California Polytechnic State Univeristy. “Viewpoint: Look Before Taking Another Leap For Mankind- Ethical and Social

Considerationa in Rebuilding Society in Space” Astropolitics. < http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14777620601039701.>

If not for adventure or knowledge, there are other, more pragmatic reasons to consider. For example, notable

scientists, like the late Carl Sagan and

‘‘backing up the biosphere’’ in case our world becomes uninhabitable. Of course, if that ever

happened, it may be our own fault, given our weapons of mass destruction, freely-distributed recipes for the 1918 killer virus,

predicted misapplications of biotechnology and nanotech nology, and other possible man-made catastrophes. So is it a

good enough reason to inhabit another planet, because we want a ‘‘do over’’ if we destroy our own? And if so, again, what

are we doing to ensure that we do not make the same mistakes and lay waste to another biosphere? If we have put

ourselves in a position where we need a back-up plan, it is unclear how settling space will improve our selfdestructive tendencies until we address those root issues. Less metaphysically, does having a safety net, such as a back up planet, make it

Stephen Hawking, discuss

more likely that we take more chances and treat our home planet less carefully? This would seem to be consistent with human behavior: as risks decrease, we

are more likely to engage in that activity. However, an argument might be made that people who engage in possibly catastrophic acts are not the kind of people

worried about our future and would proceed ahead regard less of a back-up biosphere. Further, perhaps having a ‘‘Plan B’’ does make sense, if we think that a

natural apocalypse may occur, such as an asteroid collision. Another related reason for space development is that inhabit ing other planets is the ‘‘social release

valve’’ we need to alleviate overcrowding and diminishing resources here on our home planet. But is this an argument for space exploration, or

for population control and more intelligent use of our natural resources? Once again, if we need to escape our own planet

for societal, political, or economic reasons, what is our plan for doing it right on another planet, or will we be bringing

the same baggage into space to create more of the same? Another reason, and one that is perhaps too straightforward, was recently

articulated by Elon Musk, co-founder of PayPal and founder of SpaceX: ‘‘My goal is to make humans the first interplan etary species.’’5 Although similar remarks

have been made else where, by Stephen Hawking, Carl Sagan, and Robert Zubrin to name a few, Musk is actually in a unique position to realize this goal, so it is

important to look at his particular motivations. Musk’s reason seems to speak either to our biological drive to propagate our own genetic lines, which incidentally

serves to continue the species, or to a more narcissistic desire to literally take over that which is within our reach. Either case should give us pause: what

are

the ethics of introducing new species to environments where they are not normally found, and is the fact that we can

send the average citizen into space and extend the human species on other planets or moons reason enough to do

it? And why humans—would we have a moral issue with populating the Moon with monkeys or dandelions instead? This may seem to be a ridiculous question,

until we recognize various compelling arguments in philosophy that there is nothing intrinsically special about being human or that some animals should have the

same moral status as people do.6 At any rate,

without invoking God or some metaphysical right, it is very difficult to explain why

human interests are more valuable than non-human interests, making our space quest seem much less noble and

much more selfish. Even if a more defensible reason is that space exploration pushes human limits, that drive to break past existing boundary surely must

be subject to reasonable limitations. For instance, we are able to clone human beings, yet we refrain from that practice for ethical reasons. We are physically able

to build homes inside national parks and other uninhabited areas, but we refrain from doing so, at least to comply with laws designed to preserve that

environment.

Issues like space debris prove that even if we do get off the rock, there is no way to

secure humanity. The 1AC’s description of problem solving cannot be trusted. We

will carry our current problems into space

Lin, 06. Patrick, Assistant Professor at California Polytechnic State Univeristy. “Viewpoint: Look Before Taking Another Leap For Mankind- Ethical and Social

Considerationa in Rebuilding Society in Space” Astropolitics. < http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14777620601039701.>

One of the first and natural reactions of many is to ask: should

we be encouraging private space exploration, given what we have

done to our own planet? What is to prevent problems on Earth from following us into outer space, if we have not

evolved the attitudes, and ethics, which have contributed to those problems? As examples, an over-developed sense

of nationalism may again lead to war with other humans in space, and ignoring the cumulative effects of small acts

may again lead to such things as the over- commercialization of space and space pollution. Have we learned enough about

ourselves and our history to avoid the same mistakes as we have made on Earth? Preserving the pristine, unspoiled expanses of space is a recurring theme,

much as it is important to preserve wetlands,rainforests, and other natural wonders here on Earth. We

have already littered the orbital

environment in space with floating deb ris that we need to track so that spacecraft and satellites navigate around, not

to mention abandoned equipment on the Moon and Mars. So what safeguards are in place to ensure we do not

exacer bate this problem, especially if we propose to increase space traf fic? Furthermore, are we prepared to risk

accidents in space from the technologies we might use, such as nuclear power?

I am going to beat you with my baby bump.

11

SCFI 2011

Enclosure K (Space Daesins)

Silent Nihilists.

___ of ___

The “rock” is not going anywhere. The 1AC disaster scenario is an example of how

politicians use doomsday claims to exploit outer space. The only people who would

leave would be the elite.

Dickens and Ormrod 7 - *Visiting Professor of Sociology at the University of Essex AND **Lecturer in Sociology at the University of

Brighton (Peter and James, Cosmic Society: Towards a Sociology of the Universe pg 156-157, dml)

On the other hand, some sociologists have started mirroring the arguments of pro-space advocates and are considering the development of space resources as

a permanent resolution of the second contradiction, and working this into a fundamental critique of Marx’s political economy (Thomas-Pellicer 2004). This raises

some of the debates surrounding the second contradiction thesis. Like the proponents of capitalism’s infinite expansion into an infinite

outer space, the second contradiction thesis can be seen as depending on a form of catastrophism: the idea that society

and nature are doomed. But, first, it is not clear that this is an accurate account of the Left version of the second contradiction. O’Connor (1996) is the

leading contemporary Marxist proponent of the second contradiction and he argues that it is most likely to be addressed by state intervention and limited state

ownership of the means of production. But the picture of catastrophism, whether propounded by Left or Right, is quite misleading. Whatever

happens to the Earth and the cosmos there will still be some form of a nature there (Harvey 1996). Certainly some

people, specifically the poor, may come off much worse than others as a result of such humanization. But this is a long way

from saying that capitalism and nature will come to an end as a result of commodification and environmental degradation. As pro-space activists show, the

pessimism of the second contradiction thesis can easily be adopted not just by socialists but by the promoters of capitalism

who would use the possibility of the Earth’s ‘demise’ as an excuse to continue privatizing the cosmos. One example is the

revenue generated by Earth-imaging satellites, used largely to monitor climatic and environmental change. Harris and Olby (2000) projected a market of $6.5

billion in 2007 for Earth observation data and services. Developing the rest of the cosmos entails what Enzensberger (1996) might call the next stage of the ecoindustrial complex: providing economic opportunities for those in the business of rectifying the degradation caused by capitalism in the first instance.

Humanizing nature on Earth or in the cosmos need be neither a complete disaster nor a complete triumph. The

priority for historical materialism is to consider the implications of outer space humanization for particular societies ,

particular sectors of the population and particular species and ecological systems.

I am going to beat you with my baby bump.

12

SCFI 2011

Enclosure K (Space Daesins)

Silent Nihilists.

___ of ___

Link: Econ

Using the economy as a justification for exploration and development is simply the

commodification of space

Gouge, 02.Catherine, West Virginia University. “The Great Storefront of American Nationalism: Narratives of Mars and the Outerspatial Frontier”

Americana: The Journal of American Popular Culture (1900-present), Fall 2002, Volume 1, Issue 2

http://www.americanpopularculture.com/journal/articles/fall_2002/gouge.htm

From the perspective of those moving in to explore and colonize, prospective

frontiers are, on the other hand, a space of unfulfilled hopes

and dreams, a fantasy space of unlimited socioeconomic potential. And it is this potential which marketers of frontier

technologies and proponents of frontier exploration often exploit to secure public support. Accordingly, the twentiethcentury American public was encouraged to associate a desire to explore outer space, in which media

representations and science fiction invested so deeply, with two things: citizenship and products they could buy . In the

1920s, American market specialists learned that by altering the packaging and appearance of a product, they could increase public desire for it (McCurdy 209).

Consequently, especially in the years following the Great Depression, product designers manipulated product sizes, shapes, and colors to mimic the sleek,

aerodynamic lines and polished finishes of various "frontier technologies": trains, airplanes, and, eventually, rockets. The average American citizen,

or so the logic went, could participate in the frontier, the great storefront of American nationalism, by buying things.

Owning Teflon frying pans and consuming products like Tang were markers of good citizenship. And planned obsolescence, primarily in technology markets,

became a strategy for smart business, a strategy further fueled by the pattern of the early space program, which frequently substituted rockets and spacecraft

with newer models. The official website for NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory continues the project of conveying an intimacy between the development of outerspatial frontier technologies and the United States economy. In fact, one section of the site devoted to NASA's official "U.S. Commercial Technology Policy,"

formulated in 1995, includes portions of Bill Clinton's 1993 U.S. Technology Policy that ask NASA to foster its involvement in the "progress of the nation" by

developing "new ways of doing business." 1 3 . "Since 1958," the policy reads, "NASA has been an important source of much of the nation's new technology."

The site proceeds to explain that in "today's increasingly competitive global economic climate, the U.S. must ensure that its technological resources are fully

utilized throughout the economy." And this means, according to the site, that NASA must accept a "new, broader role" in the future of this nation: "While

meeting its unique mission goals, NASA Research and Development must also enhance overall U.S. economic

security." The site imagines this dynamic as one in which NASA essentially feeds its "technological assets and knowhow" into U.S. economic growth. This should be done, the site maintains, by "quickly and effectively translat[ing]" NASA's

assets and know-how "into improved production processes and marketable, innovative products." In order to accomplish this, the agency must find "new ways of

doing business and new ways of measuring progress." Indeed, as this NASA policy makes clear, there is no such thing as a purely

scientific project. NASA's current official technology policy is, thus, on one level, a utopian projection or science

fiction that imagines the productive power of NASA technologies to "enhance overall U.S. economic security."

I am going to beat you with my baby bump.

13

SCFI 2011

Enclosure K (Space Daesins)

Silent Nihilists.

___ of ___

Link: Infinite Resources

The idea that space has “infinite” resources is indicative of the need to exploit and

colonize space. This is rooted in American imperialism.

Gouge, 01 Catherine, Doctor of Philosophy in English at West Virginia University. “The American Frontier: History, Rhetoric, Concept” Americana: The

Journal of American Popular Culture (1900-present), Spring 2007, Volume 6, Issue 1

http://www.americanpopularculture.com/journal/articles/spring_2007/gouge.htm

Indeed, in the service of resolving the contradictions between the economic and political imperatives of liberal democracy in the United States, many latetwentieth century frontierist American narratives commodify and reify citizenship and progress as if they could be separated from a history of exclusion and

disenfranchisement. Frank Chin’s Donald Duk (1991), for example, works within a frontierist structure to redefine Chinese-American men as powerful and

significant members of American culture because of their participation in building the transcontinental railroad both to “open” and, in some respects, “close” the

originary frontier West6. Consequently, some contemporary narratives of identity formation reinvest frontier spaces and

technologies with the power to validate one as a productive citizen. The rhetoric of the exploration of outer space

participates in a frontierist discourse which emphasizes the economic 6 This is because the railroad brought people and commerce to

the West and connected the West to eastern commerce which led to the 1890 Census’ declaration I cite at the start of this introduction. 9promise of

colonizing space and redefines the productive citizen to include one who consumes products said to be of the

frontier. Similarly, the rhetoric of figuratively exploring and “homesteading” cyberspace in advertisements for

computer technology emphasizes the power and control afforded to Americans who purchase the latest technology

and invests in a notion of an American citizen-consumer who can participate in frontiers by purchasing cyberspatial

frontier-related technologies. My dissertation is a critique of notions of American exceptionalism, such as these,

which are founded on the frontierist logic at work in contemporary narratives of the technologies of literal and

figurative frontier ventures. The first chapter discusses the wide-spread influences of Turner’s ideas about the value of the originary frontier to

consolidate the boundaries of American citizenship. It surveys twentieth-century histories of the frontier to consider the language that has been used to define the

originary frontier West. The chapter draws the conclusion that, in

spite of the many and varied perspectives provided by revisionist and

new historians, Turner’s romanticized concept of the frontier, especially a logic of equal opportunity, is frequently

unselfconsciously transposed onto other, twentieth-century “frontiers.”Lewis Corey argued in The Decline of American Capitalism

(1934) that the “‘expansion of the frontier’ had ensured the growth of capitalism in America, and the industrial boom of the

1920s had sustained its growth” (qtd. in Wrobel 139). Indeed, supporting the expansion of capitalism, a great many twentieth-century texts (artistic,

historical, political, etc.) have further defined and named frontiers for the American public in consumerist terms. The American media have sold

everything from outer space to cyberspace to Velcro to pizza delivery services as vehicles for participating in a

national, collective frontier venture, a way of allegedly increasing our power both as individuals and as citizens of an

increasing powerful and wealthy, capitalist American nation-state. These pronouncements of literal and figurative frontier ventures,

as my project seeks to demonstrate, work in the service of an ideology of frontierism which insists that we must continue to be consumerist

frontier subjects--and we therefore must continue to name and pursue various frontiers in science, technology,

physical spaces, and bodily spaces--or cease to be “American.” Indeed, late-twentieth century narratives of travel

through outer and cyberspaces thus use the discourse of exploration and empire building to invoke romantic

Turnerian associations of exploring and settling the American frontier West and, ultimately, rewrite what exploration

and empire-building are; and some narratives which work to expand the boundaries of American citizenship to create

a space for excluded minority groups do so by anchoring the identity category to a frontierist fiction. Such narratives

emphasize, as Turner’s did over a century before, the displacement of the “American dream” of unlimited resources

to a space that is always just beyond, emphasizing the ways in which frontiers regulate a psychic national identity which structures itself through a

frontierist episteme. Feeding this national self-regard, Ronald Reagan proclaimed at an Independence Day celebration in 1982 that the “conquest of new frontiers

is a crucial part of our national character” (qtd. in Limerick 84). To put it simply, as inheritors of this investment in the power of the frontier, to be “American” in the

late- twentieth century, or so the logic goes, we need frontiers. Consequently, even the rhetoric of twentieth-century American narratives of

“new” frontier spaces imports an ideology of the originary American frontier which is predicated on the assumption

that exploring and colonizing frontier spaces has been integral to the formation of a distinctly American national

identity.

I am going to beat you with my baby bump.

14

SCFI 2011

Enclosure K (Space Daesins)

Silent Nihilists.

___ of ___

Links- exploration

Using exploration as means to solve problems on earth is rooted in the false

assumption that capitalism can be fixed. Conquering the cosmos is not the solution

but will only create more capitalist problems

Dickens 10 Visiting Professor of Sociology at the University of Essex

(Peter, “The Humanization of the Cosmos – To What End?”, Monthly Review Vol 62,

No 6, November 2010, dml)

Instead of indulging in over-optimistic and fantastic visions, we

should take a longer, harder, and more critical look at what is

happening and what is likely to happen. We can then begin taking a more measured view of space humanization,

and start developing more progressive alternatives. At this point, we must return to the deeper, underlying processes which

are at the heart of the capitalist economy and society, and which are generating this demand for expansion into outer

space. Although the humanization of the cosmos is clearly a new and exotic development, the social relationships and

mechanisms underlying space-humanization are very familiar. In the early twentieth century, Rosa Luxemburg argued that an “outside” to

capitalism is important for two main reasons. First, it is needed as a means of creating massive numbers of new customers who would buy the goods made in the

capitalist countries.7 As outlined earlier, space technology has extended and deepened this process, allowing an increasing number of people to become integral

to the further expansion of global capitalism. Luxemburg’s second reason for imperial expansion is the search for cheap supplies of labor and raw materials.

Clearly, space fiction fantasies about aliens aside, expansion into the cosmos offers no benefits to capital in the form of fresh sources of labor power.8 But

expansion into the cosmos does offer prospects for exploiting new materials such as those in asteroids, the moon,

and perhaps other cosmic entities such as Mars. Neil Smith’s characterization of capital’s relations to nature is useful at this point. The

reproduction of material life is wholly dependent on the production and reproduction of surplus value. To this end , capital stalks the Earth in search

of material resources; nature becomes a universal means of production in the sense that it not only provides the subjects, objects and

instruments of production, but is also in its totality an appendage to the production process…no part of the Earth’s surface, the atmosphere, the oceans, the

geological substratum or the biological superstratum are immune from transformation by capital.9 Capital is now also “stalking” outer space in

the search for new resources and raw materials. Nature on a cosmic scale now seems likely to be incorporated into

production processes, these being located mainly on earth. Since Luxemburg wrote, an increasing number of political economists have argued that the

importance of a capitalist “outside” is not so much that of creating a new pool of customers or of finding new resources.10 Rather, an outside is needed as a

zone into which surplus capital can be invested. Economic and social crisis stems less from the problem of finding new consumers, and

more from that of finding, making, and exploiting zones of profitability for surplus capital. Developing “outsides” in this way

is also a product of recurring crises, particularly those of declining economic profitability. These crises are followed by attempted

“fixes” in distinct geographic regions. The word “fix” is used here both literally and figuratively. On the one hand, capital is being physically invested in new

regions. On the other hand, the attempt is to fix capitalism’s crises. Regarding the latter, however, there are, of course, no absolute guarantees that such fixes

will really correct an essentially unstable social and economic system. At best, they are short-term solutions. The kind of theory mentioned above also has clear

implications for the humanization of the cosmos. Projects for the colonization of outer space should be seen as the attempt to

make new types of “spatial fix,” again in response to economic, social, and environmental crises on earth. Outer

space will be “globalized,” i.e., appended to Earth, with new parts of the cosmos being invested in by competing nations and

companies. Military power will inevitably be made an integral part of this process, governments protecting the zones for which they

are responsible. Some influential commentators argue that the current problem for capitalism is that there is now no “outside.”11

Capitalism is everywhere. Similarly, resistance to capitalism is either everywhere or nowhere. But, as suggested

above, the humanization of the cosmos seriously questions these assertions. New “spatial fixes” are due to be

opened up in the cosmos, capitalism’s emergent outside. At first, these will include artificial fixes such as satellites,

space stations, and space hotels. But during the next twenty years or so, existing outsides, such as the moon and Mars, will begin

attracting investments. The stage would then be set for wars in outer space between nations and companies

attempting to make their own cosmic “fixes.”

I am going to beat you with my baby bump.

15

SCFI 2011

Enclosure K (Space Daesins)

Silent Nihilists.

___ of ___

The harms outlined in the 1AC are symptoms of capitalism. Development and

exploration cannot solve

Dickens 10 Visiting Professor of Sociology at the University of Essex (Peter, “The Humanization of the Cosmos – To What End?”, Monthly Review Vol 62,

No 6, November 2010, dml

The imminent conquest of outer space raises the question of ‘outside’ and ‘inside’ yet again. Capitalism now has the

cosmos in its sights, an outside which can be privately or publicly owned, made into a commodity, an entity for which nations

and private companies can compete. As such the cosmos is a possible site of armed hostilities. This means, contra Hardt and Negri, that there

is an outside after all, one into which the competitive market can now expand indefinitely. A new kind of imperialism is therefore underway,

albeit not one attempting to conquer and exploit people ‘outside’ since there are no consumers or labour power to exploit in other parts of the solar system.

Ferrying wealthy tourists into the cosmos is a first and perhaps most spectacular part of this process of capital's cosmic expansion. Especially

important

in the longer term is making outer space into a source of resources and materials. These will in due course be

incorporated into production-processes, most of which will be still firmly lodged on earth. Access to outer space is, potentially at least,

access to an infinite outside array of resources. These apparently have the distinct advantage of not being owned or used by any pre-existing

society and not requiring military force by an imperializing power gaining access to these resources. Bringing this outside zone into capitalism

may at first seem beneficial to everyone. But this scenario is almost certainly not so trouble-free as may at first seem. On the

one hand, the investment of capital into outer space would be a huge diversion from the investments needed to address

many urgent inequalities and crises on Earth. On the other hand, this same access is in practice likely to be conducted by a range of competing

imperial powers. Hardt and Negri (2000) tell us that the history of imperializing wars is over. This may or may not be the case as regards imperialism on earth.

But old-style imperialist, more particularly inter-imperialist, wars seem more likely than ever, as growing and competing power-blocs (the USA and China are

currently amongst the most likely protagonists) compete for resources on earth and outer space. Such, in rather general terms, is the prospect for a future,

galactic, imperialism between competing powers. But what are the relations, processes and mechanisms underlying this new phenomenon? How should we

understand the regional rivalries and ideologies involved and the likely implications of competing empires attempting to incorporate not only their share of

resources on earth but on global society's ‘outside’? Social crises, outer spatial fixes and galactic imperialism Explanatory primacy is given here to economic

mechanisms driving this humanization of the universe. In the same way that they have driven imperializing societies in the past to expand their economic bases

into their ‘outsides’, the

social relations of capitalism and the processes of capital-accumulation are driving the new kind of

outer space imperialisms. Such is the starting-point of this paper (See alsoDickens and Ormrod, 2007). It is a position based on the work of the

contemporary Marxist geographer David Harvey (2003) and his notion of ‘spatial fixes’. Capitalism continually constructs what he calls ‘outer transformations.’ In

the context of the over-accumulation of capital in the primary circuit of industrial capital, fresh geographic zones are constantly sought out

which have not yet been fully invested in or, in the case of outer space, not yet been invested in at all. ‘Outer spatial fixes’ are

investments in outer space intended to solve capitalism's many crises. At one level they may be simply described as crises of

economic profitability. But ‘economic’ can cover a wide array of issues such as crises of resource-availability and potential social and political upheavals resulting

from resource-shortages. Furthermore, there is certainly no guarantee that these investments will actually ‘fix’ these underlying

economic, political and social crises. The ‘fix’ may well be of a temporary, sticking-plaster, variety.

I am going to beat you with my baby bump.

16

SCFI 2011

Enclosure K (Space Daesins)

Silent Nihilists.

___ of ___

Link: Colonizing

The idea of colonizing is inherently capitalist because it determines which lands are

the “unknown” and turns them into “safe”, “productive lands” that can then be used

to gain more capital and used to exploit the people living there.

Spanos 2009 (Willam V.Distinguished Professor of English and comparative literature at Binghamton University, “Disclosing Enclosure,” symploke,

Volume 17, Numbers 1-2, 2009, pp. 307-315 (Review), MUSE, JR2)

Following the lead offered by Michel Foucault’s critical genealogy of (Western) modernity, which, among other related instruments of knowledge production such

as panoptics (viewing the differential phenomena of being from above, i.e., metaphysically), appropriated the classificatory table on behalf of reforming and

domesticating the errant multitude and establishing the disciplinary society, Marzec shows, very persuasively indeed, that the

massive movement to

enclose the open —and thus “unproductive” and “threatening”—Commons culminating in the eighteenth century was a

fundamentally related, indeed, inaugural aspect of this history of “improvement.” It was a symptom of an emergent

and indissolubly related ontological/cultural logic—a “technology” of challenge, in Heidegger’s terms, or, in the more nuanced terms

of Deleuze and Guattari, an “apparatus of capture”—that separated and alienated humans, both materially and ideologically,

from the land which they inhabited, reducing it to a utilitarian means of producing “standing reserve” (Bestand: Heidegger)

or of “stockpiling” (Deleuze and Guattari) and those who worked it (Georgoi: ge-ourgoi: earth workers) to “docile bodies” at the disposal of

the disciplinary society. Under this metaphysical regime of deterritorializing territorialization and the disciplinary

compartmentalization of the be-ing of being, an epochal metamorphosis of the relation being human beings and the

land takes place. On the one hand, the “inhabitants” of the open Commons—a key word in this study, the meaning of which

ultimately derives from Heidegger’s understanding of “dwelling” as a relationality incumbent on being-in-the midst (inter

esse), a non-essentialist, as opposed to a quantitative and essentialist matter—come to be represented as nomadic

aliens or predatory vagabonds— sylvestres (Roman: forest dwellers/savages), though Marzec does not invoke this etymology—to be settled,

domesticated, and exploited or exterminated. On the other hand, the land becomes a wilderness, an unproductive national and global

space to be objectified, enclosed, gridded, and “improved”: the space of “stockpiling.” This epochal panoptic/disciplinary initiative

of the British Enlightenment vis-à-vis the coding of the land, Marzec shows, especially in his reading of Defoe’s Tour, not only produced the “free”

capitalistic individual and the “truth” of private property. It also produced the idea of the British nation understood as a circuitry

of enclosed and “colonized” land emanating from and serving the authority of the metropolitan center (London). Equally

important, as the binarist language of domination disclosed by Marzec’s genealogy of the benign truth discourse of

individualist, democratic capitalism (Enlightenment modernity) suggests, it also inaugurated the British imperial/colonial project.

In establishing a (hegemonic) truth discourse informed by a white metaphorics privileging vision (“prospect,” “oversight,”

“supervision,” “survey,” “surveillance”) in the production of knowledge, specifically the circle in which every singular thing and

event takes it proper place according to the imperatives of the fixed center elsewhere—the center that measures—

this metaphysical comportment toward the earth that produced the nation state also gave rise to the imperial

metropolis. And this onto-cultural-political relation constitutes his most important contribution to postcolonial literary

studies.

I am going to beat you with my baby bump.

17

SCFI 2011

Enclosure K (Space Daesins)

Silent Nihilists.

___ of ___

Link: GPS/Positioning

Distribution of technology retrenches us in the identity of consumerism, constantly

attempting to move to the periphery in order to observe acts of violence, this

shouldn’t be dismissed easily it’s what create the “patriotic” articulations of security

prosperity and freedom

Kaplan 2006 (Caren, director of the Cultural Studies Graduate Group and associate professor in women and gender studies at the University of California,

Precision Targets: GPS and the Militarization of U.S. Consumer Identity,” American Quarterly 58.3 (2006) 693-713, MUSE, JR2)

For most people in the United States, war is almost always elsewhere. Since the Civil War, declared wars have been

engaged on terrains at a distance from the continental space of the nation. Until the attacks on the World Trade towers and the

Pentagon in September 2001, many people in the United States perceived war to be conflicts between the standing armies of

nation-states conducted at least a border—if not oceans and continents—away. Even the attacks of September 11 were localized in

such a way as to feel as remote as they were immediate—watching cable news from elsewhere in the country, most U.S. residents were brought close to scenes

of destruction and death by the media rather than by direct experience. Thus, in

the United States, we could be said to be "consumers" of

war, since our gaze is almost always fixed on representations of war that come from places perceived to be remote

from the heartland. Digital communications and transnational corporate practices are transforming the modes,

locations, and perceptions of nationalized identities as well as the operations of contemporary warfare. Certainly, war

is consumed worldwide by global, as well as national, audiences. Indeed, if the conflicts of the present age cannot be

described as between nation-states but as between the extra- or transnational symbols of political, religious, and

cultural philosophies or ideologies, drawing on national identity becomes a more challenging task. Yet, conditions specific to

the United States need to be explored in relation to the network of discourses, subjects, and practices that make up our nation and its government. The

United States still signifies a coherent identity, if only as the enemy or perpetrator of attacks against people outside

its national borders or as the defender of borders that are perceived by many of its residents as too porous and

insecure. Situating the cultural, political, and economic workings [End Page 693] of the United States within