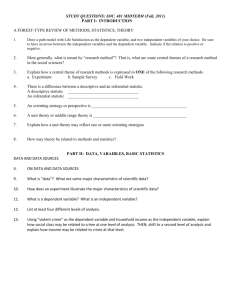

UnitIIModel

advertisement

Gender and Crime According to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (2012), 74.5% of the over twelve million people arrested in the United States in 2012 were male, reflecting an international trend that has existed for centuries. It was once thought that female crime rates would come to approximate those of males as the genders assumed more similar roles in society. But this so-called “gender gap” in crime still remains with only a 2.9% increase in female crime rates observed in the last 10 years (FBI 2012). Studies have shown that the social status of male and female criminals are generally the same, disproportionally representing those with a low level of education, minorities, and the under- or unemployed (Steffensmeier 1996). Something, then, has to account for this disparity in crime rates between the genders. Psychological motivation, as manifested in the stereotypes, physicality, and mental traits of the genders, can be shown to greatly impact the gender gap in crime. Stereotypical gender roles influence motivations to commit crime. Men are usually viewed as aggressive and dominating while women are seen as caring and nurturing. Criminal behavior is typically associated with masculine rather than feminine qualities. Aggression, independence, and dominance seem to lead naturally to deviance while most crime seems directly opposed to the nurturing feminine image. In fact, Dr. Steffensmeier, a criminologist at Penn State University, noted that “the cleavage between what is considered feminine and what is criminal is sharp, while the dividing line between what is considered masculine and what is criminal is often thin” (Steffensmeier, 1996, 19). Another study noted that “in committing crime, females violate their gender role expectations” (KoonsWitt, 2003, 1). Women may lose motivation to commit criminal acts from these social stereotypes of gender and criminals, afraid that a stigma may be attached to them for exhibiting more masculine qualities in their actions. Like most stereotypes, there are some good reasons for these ideas of traditional gender traits to exist, as exhibited by innate physical and mental differences between the genders. Physical differences are due largely to testosterone, a hormone found biologically in both men and women but in much higher amounts in men. Elevated levels of testosterone cause increased bodily and muscular growth and strength and tend to make men naturally more aggressive and dominant. Studies have linked typical masculine testosterone levels to increased aggression (Archer 2006) and risk taking (Coren 2008). In general, it was noted that “behavior associated with testosterone can lead to trouble with the law.” (Dabbs, 1997, 477). Conversely, lower levels of testosterone make women physically weaker, less aggressive, and more group-oriented. For these reasons, females are less likely to commit crime than males and when they do, they often act in groups or as accomplices to male criminals (Steffensmeier 1996). Key mental differences also exist between the genders. Fumagalli et al (2009) found a fundamental difference in moral reasoning between the males and females. While men tended to make moral decisions based on abstract concepts like justice and fairness and preferred to deal with such problems themselves, women based their reasoning on the choice that would cause the least amount of moral and physical pain to others and were less likely to act on their own. Women criminals are also more likely to have a history of psychological disorders and are more likely to be victims of physical, sexual, or drug abuse (Chambers 2001, Steffensmeier 1996), which may contribute to their likelihood to commit crime. Another study showed that women are actually more likely to deal with negative emotions that could lead to crime (such as anger) in constructive ways and often empathize with crime victims, deterring them from committing crime themselves (Knight 2002). Finally, males are typically rewarded for taking risks in childhood (Bowen 2009) and usually receive a higher payoff from the crimes that they commit (Bowen 2009, Steffensmeier 1996), which also makes them more motivated to commit crime. These differences in motivation combine to significantly impact the crime rate. Violent crime, which includes murder, rape, and robbery, exhibits the largest difference in crime rates between the genders, with only 20% of these offenses committed by females (FBI 2012). As we have seen, men are motivated primarily by power and individualism and are more likely to take risks and act aggressively. Men are thus more likely to participate in violent crime. On the other hand, women turn to violence typically as a last resort when under extreme stress. A study noted that “females appeared motivated by selfpreservation” (Chambers, 2011, 15), and Steffensmeier (1996) found that “for women to kill, they generally must see their situation as life-threatening, as affecting the physical or emotional well-being of themselves of their children” (p. 23). These findings that help explain psychological motivation in crime while also reaffirming stereotypical gender qualities. On the other side of the spectrum is white collar crime, a category that includes forgery, fraud, and embezzlement. The difference in this crime rate is still significant, with males committing 59.9% of these offenses (FBI 2012). Men have a more individualistic moral sense, are higher risk takers, and typically have a higher payoff, and so are more motivated to commit these crimes. Because females, on the other hand, are more empathetic, do not take as much risk, and have a far lower payoff, they are less likely to commit white collar crime. Steffensmeier (1996) showed that women do not take advantage of opportunities to commit these offenses nearly as often as men, and the rates even decrease as women climb company ranks, providing further evidence of the moral difference between the genders. Because the traditional gender roles, physical qualities, and mental traits of the genders differ systematically, psychological motivation between them also varies. Masculine qualities naturally lead to a higher level of motivation for men to commit crime— the gender gap is real. In light of this conclusion, Steffensmeier (in Swayne 2013) went as far as to suggest that more females should be appointed to high-level corporate positions to guard against white collar crime. Approaches to criminal outreach and rehabilitation should also be reconsidered, as most female criminal rehabilitation programs are based on male models and have been shown to be relatively unsuccessful in preventing crime recurrence (Chambers 2011). Male programs should be reformed as well in order to decrease the overall crime rate and make America a safer place to live. References Archer, J. (2006). Testosterone and human aggression: an evaluation of the challenge hypothesis. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 30:319-345. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0149763405000102. Bowen, D. (2009). Gender and crime and criminal justice. Encyclopedia of Gender and Society. Ed. Jodi O’Brien. 172-8. Retrieved from http://knowledge.sagepub.com/view/gender/n96.xml. Chambers, J.C, Ward, T., Eccleston, L., & Brown, M. (2011). Representation of female offender types within the pathways model of assault. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 55(6) 925-48. Retrieved from http://ijo.sagepub.com/content/55/6/925.full.pdf+html. Coren. A. L., Dreber, A., Campbell, B., Gray, P. B., Hoffman, M., Little, A. C. (2008). Testosterone and financial risk preferences. Evolution and Human Behavior. 29(6):384 390. Retrieved from http://www.fas.harvard.edu/~ped/publications/PEDpublications/2008/Testostero ne.pdf. Dabbs, J. M., Hargrove, M. F. (1997). Age, testosterone, and behavior among female prison inmates. Psychomatic Medicine. 59(5):477-480. Retrieved from UNC Database. Federal Bureau of Investigation (2012). Uniform Crime Reports. Retrieved from http://www.fbi.gov/about-us/cjis/ucr/crime-in-the-u.s/2012/crime-in-the-u.s. 2012/tables/33tabledatadecoverviewpdf. Fumagalli, M., et al. (2009). Gender related-differences in moral judgments. Cogn Process 11. Retrieved from http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10339-009-03352/fulltext.html. Knight, G. P., Guthrie, I. K., Page, M. C., Fabes, R.A. (2002). Emotional arousal and gender differences in aggression: a meta-analysis. Aggressive Behavior. 28:366-393. Retrievedq from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ab.80011/pdf. Koons-Witt, B.A., Schram, P.J. (2003). The prevalence and nature of violent offending by females. Journal of Criminal Justice. 31(4) 361-71. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S004723520300028X. Steffensmeier, D., Allen, E. (1996). Gender and crime: toward a gendered view of female offending. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 22:359-87. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2083439. Swayne, Matthew. (2013). Women still less likely to commit corporate fraud. Penn State News. Retrieved from http://news.psu.edu/story/284069/2013/08/13/research/women-still-less likelycommit-corporate-fraud.