Information about long-term outcomes of language

advertisement

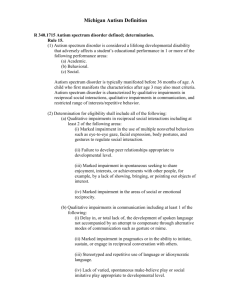

Information about long-term outcomes of language impairments in children Some references with abstracts compiled by Dorothy Bishop 16th December 2014 There are several longitudinal studies, where children identified with language problems are followed up over time. As far as I know, none of these has looked at intervention: some children will have had intervention and others not, but it has not been systematically investigated. In practice this often means that you end up finding that the children who had intervention are the ones with worst outcome, but this is almost certainly because those with the most severe difficulties are the most likely to receive special help. Results from specific studies will depend on the way the sample was recruited, who was included and how severe the problems were. I will list below the main studies and an abstract of the findings. Please note that many studies describe only the average outcome, but my impression of the literature (and our own studies) is that there is a lot of variation from one individual to the next. This book by Beitchman and Brownlie is recommended as a good overview of the topic as a whole: Beitchman, J. H., & Brownlie, E. B. (2013). Language disorders in children and adolescents. Boston: Hogrefe Clegg, J., Hollis, C., Mawhood, L., & Rutter, M. (2005). Developmental language disorders - a follow-up in later life. Cognitive, language and psychosocial outcomes. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46, 128-149. BACKGROUND: Little is known on the adult outcome and longitudinal trajectory of childhood developmental language disorders (DLD) and on the prognostic predictors. METHOD: Seventeen men with a severe receptive DLD in childhood, reassessed in middle childhood and early adult life, were studied again in their mid-thirties with tests of intelligence (IQ), language, literacy, theory of mind and memory together with assessments of psychosocial outcome. They were compared with the non language disordered siblings of the DLD cohort to control for shared family background, adults matched to the DLD cohort on age and performance IQ (IQM group) and a cohort from the National Child Development Study (NCDS) matched to the DLD cohort on childhood IQ and social class. RESULTS: The DLD men had normal intelligence with higher performance IQ than verbal IQ, a severe and persisting language disorder, severe literacy impairments and significant deficits in theory of mind and phonological processing. Within the DLD cohort higher childhood intelligence and language were associated with superior cognitive and language ability at final adult outcome. In their midthirties, the DLD cohort had significantly worse social adaptation (with prolonged unemployment and a paucity of close friendships and love relationships) compared with both their siblings and NCDS controls. Self-reports showed a higher rate of schizotypal features but not affective disorder. Four DLD adults had serious mental health problems (two had developed schizophrenia). CONCLUSION: A receptive developmental language disorder involves significant deficits in theory of mind, verbal short-term memory and phonological processing, together with substantial social adaptation difficulties and increased risk of psychiatric disorder in adult life. The theoretical and clinical implications of the findings are discussed. Note by DVMB: When originally recruited, children in this sample had severe comprehension problems. It is likely that many of those identified as having ‘receptive language disorder’ would nowadays receive a diagnosis of ASD. Johnson, C. J., Beitchman, J. H., & Brownlie, E. B. (2010). Twenty-year follow-up of children with and without speech-language impairments: family, educational, occupational, and quality of life outcomes. American Journal of Speech Language Pathology, 19(1), 51-65. PURPOSE: Parents, professionals, and policy makers need information on the long-term prognosis for children with communication disorders. Our primary purpose in this report was to help fill this gap by profiling the family, educational, occupational, and quality of life outcomes of young adults at 25 years of age (N = 244) from the Ottawa Language Study, a 20-year, prospective, longitudinal study of a community sample of individuals with (n = 112) and without (n = 132) a history of early speech and/or language impairments. A secondary purpose of this report was to use data from earlier phases of the study to predict important, real-life outcomes at age 25. METHOD: Participants were initially identified at age 5 and subsequently followed at 12, 19, and 25 years of age. Direct assessments were conducted at all 4 time periods in multiple domains (demographic, communicative, cognitive, academic, behavioral, and psychosocial). RESULTS: At age 25, young adults with a history of language impairments showed poorer outcomes in multiple objective domains (communication, cognitive/academic, educational attainment, and occupational status) than their peers without early communication impairments and those with early speech-only impairments. However, those with language impairments did not differ in subjective perceptions of their quality of life from those in the other 2 groups. Objective outcomes at age 25 were predicted differentially by various combinations of multiple, interrelated risk factors, including poor language and reading skills, low family socioeconomic status, low performance IQ, and child behavior problems. Subjective well-being, however, was primarily associated with strong social networks of family, friends, and others. CONCLUSION: This information on the natural history of communication disorders may be useful in answering parents' questions, anticipating challenges that children with language disorders might encounter, and planning services to address those issues. Durkin, K., Conti-Ramsden, G., & Simkin, Z. (2012). Functional outcomes of adolescents with a history of Specific Language Impairment (SLI) with and without autistic symptomatology. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(1), 123-138. doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1224-y This study investigates whether the level of language ability and presence of autistic symptomatology in adolescents with a history of SLI is associated with differences in the pattern of difficulties across a number of areas of later functioning. Fifty-two adolescents with a history of SLI participated. At age 14, 26 participants had a history of SLI but no autistic symptomatology and 26 had a history of SLI and autistic symptomatology. At age 16, outcomes were assessed in the areas of friendships, independence, academic achievement, emotional health and early work experience for both subgroups and for 85 typically developing peers. Autistic symptomatology was a strong predictor of outcomes in friendships, independence and early work experience whilst language was a strong predictor of academic achievement. No significant associations were found for later emotional health. This is one of the more recent reports from the Manchester Language Study; there have been numerous papers from this study dealing with various aspects of outcomes at different ages. Tomblin, J. B. (2008). Validating diagnostic standards for SLI using adolescent outcomes. In C. F. Norbury, J. B. Tomblin & D. V. M. Bishop (Eds.), Understanding Developmental Language Disorders (pp. 93-114). Hove: Psychology Press. No abstract available; looks at how outcomes vary depending on whether children have specific or more general language problems on a wide range of outcome measures. Stothard, S. E., Snowling, M. J., Bishop, D. V. M., Chipchase, B. B., & Kaplan, C. A. (1998). Language impaired preschoolers: A follow-up into adolescence. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research, 41, 407-418. This paper reports a longitudinal follow-up of 71 adolescents with a preschool history of speechlanguage impairment, originally studied by Bishop and Edmundson (1987). These children had been subdivided at 4 years into those with nonverbal IQ 2 SD below the mean (General Delay group), and those with normal nonverbal intelligence (SLI group). At age 5;6 the SLI group was subdivided into those whose language problems had resolved, and those with persistent SLI. The General Delay group was also followed up. At age 15–16 years, these children were compared with age-matched normal-language controls on a battery of tests of spoken language and literacy skills. Children whose language problems had resolved did not differ from controls on tests of vocabulary and language comprehension skills. However, they performed significantly less well on tests of phonological processing and literacy skill. Children who still had significant language difficulties at 5;6 had significant impairments in all aspects of spoken and written language functioning, as did children classified as having a general delay. These children fell further and further behind their peer group in vocabulary growth over time. Whitehouse, A. J. O., Line, E. A., Watt, H. J., & Bishop, D. V. M. (2009). Qualitative aspects of developmental language impairment relates to language and literacy outcome in adulthood. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 44, 489-510. BACKGROUND: Developmental language disorder is a heterogeneous diagnostic category. Little research has compared the long-term outcomes of children with different subtypes of language impairment. AIMS: To determine whether the pattern of language impairment in childhood related to language and literacy outcomes in adulthood. METHODS & PROCEDURES: Adults who took part in previous studies as children were traced. There were four groups of participants, each with a different childhood diagnosis: specific language impairment (SLI; n = 19, mean age at follow-up = 24;8), pragmatic language impairment (PLI; n = 7, mean age at follow-up = 22;3), autism spectrum disorder (ASD; n = 11; mean age at follow-up = 21;9), and no childhood diagnosis (typical; n = 12; mean age at follow-up = 21;6). Participants were administered a battery of language and literacy tests. OUTCOMES & RESULTS: Adults with a history of SLI had persisting language impairment as well as considerable literacy difficulties. Pragmatic deficits also appeared to develop over time in these individuals. The PLI group had enduring difficulties with language use, but presented with relatively intact language and literacy skills. Although there were some similarities in the language profile of the PLI and ASD groups, the ASD group was found to have more severe pragmatic deficits and parent-reported linguistic difficulties in conversational speech. CONCLUSIONS & IMPLICATIONS: The pattern of deficits observed in different subtypes of developmental language disorder persists into adulthood. The findings highlight the importance of a wide-ranging clinical assessment in childhood, which may provide an indication of outcome in adulthood. Whitehouse, A. J. O., Watt, H. J., Line, E. A., & Bishop, D. V. M. (2009). Adult psychosocial outcomes of children with specific language impairment, pragmatic language impairment and autism. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 44, 511-528. BACKGROUND: The few studies that have tracked children with developmental language disorder to adulthood have found that these individuals experience considerable difficulties with psychosocial adjustment (for example, academic, vocational and social aptitude). Evidence that some children also develop autistic symptomatology over time has raised suggestions that developmental language disorder may be a high-functioning form of an autism spectrum disorder (ASD). It is not yet clear whether these outcomes vary between individuals with different subtypes of language impairment. AIMS: To compare the adult psychosocial outcomes of children with specific language impairment (SLI), pragmatic language impairment (PLI) and ASD. METHODS & PROCEDURES: All participants took part in research as children. In total, there were 19 young adults with a childhood history of Specific Language Impairment (M age = 24;8), seven with PLI (M age = 22;3), 11 with high functioning ASD (M age = 21;9) and 12 adults with no history of developmental disorder (Typical; n = 12; M age = 21;6). At follow-up, participants and their parents were interviewed to elicit information about psychosocial outcomes. OUTCOMES & RESULTS: Participants in the SLI group were most likely to pursue vocational training and work in jobs not requiring a high level of language/literacy ability. The PLI group tended to obtain higher levels of education and work in 'skilled' professions. The ASD participants had lower levels of independence and more difficulty obtaining employment than the PLI and SLI participants. All groups had problems establishing social relationships, but these difficulties were most prominent in the PLI and ASD groups. A small number of participants in each group were found to experience affective disturbances. The PLI and SLI groups showed lower levels of autistic symptomatology than the ASD group. CONCLUSIONS & IMPLICATIONS: The between-group differences in autistic symptomatology provide further evidence that SLI, PLI, and ASD are related disorders that vary along qualitative dimensions of language structure, language use and circumscribed interests. Childhood diagnosis showed some relation to adult psychosocial outcome. However, within-group variation highlights the importance of evaluating children on a case-by-case basis.