here

advertisement

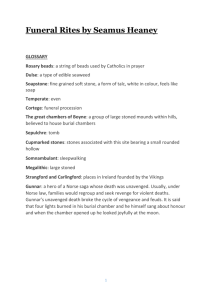

THINKING BEYOND CONFLICT AND CONFRONTATION: LESSONS FROM THE QUEST FOR PEACE If I had to borrow one statement to sum up what this presentation is about I would quote W.H. Auden: “Through art it is possible to break bread with the dead, and without communion with the dead a fully human life is impossible”. Auden practiced that art in his elegies to W. B. Yeats and to Louis MacNeice. In more recent times an exemplar would be John Adams’ work “On the Transmigration of Souls” to commemorate the lives lost on September 11, 2001; and by transmigration he meant ‘the transition of being from one state to another’ and continued ‘And I just don’t mean the transition from living to dead but also the change that takes place within the souls of those who stay behind, of those who suffer pain and loss and then they themselves come away from that experience transformed’. You might say that this presentation is about such a transmigration occasioned by the impact of intense conflict and our efforts to move beyond it. The journey of coming out of seemingly intractable conflict has been delineated by Johan Galtung as consisting of diagnosis, prognosis, therapy. We are concerned here with therapy, perhaps the most difficult. When we consider that some 50% of civil wars have terminated in peace agreements in the fifteen years after the end of the Cold War, and that is more than the previous two centuries combined, when only 1 in 5 resulted in negotiated settlements. This amounted to over 300 peace agreements in some 40 jurisdictions. And yet research suggests that nearly half of all peace agreements break down within five years and more within ten years, while many of the remainder enter a ‘no war, no peace’ limbo whose evaluation is difficult (Bell, 2006). So our thesis is simple: implementing peace may be incredibly difficult and we need to know why. I won’t be presenting any Iron Law that provides a solution but rather looking at more modest steps that offers some guidance in the journey towards peace. And I will be relying on the literature from Peace Studies and on my own practice experience. Peace Studies as an academic exercise is not universally admired. We can find objections to it throughout history. I will limit myself to two: one of which is elegant and one of which is not. The former comes from the great Conservative philosopher, Edmund Burke, when he described peace literature as ‘a commonplace against war’: the easiest of all topics. The latter appeared in the Summer of 2007 and was written by Bruce Bawer. His title – “The Peace Racket” – is a giveaway. He cites two points at the outset: ‘First, it is opposed to every value that the West stands for – liberty, free markets, individualism – and it despises America, the supreme symbol and defender of those values. Second, we’re not talking about a bunch of naïve Quakers but about a movement of savvy, ambitious professionals that is already comfortably ensconced at the U.N., in the E.U., and in many non-governmental organizations. It is already waging an aggressive under-the-media-radar campaign for a Cabinet level Peace Department in the United States’ (and he concludes) ‘… the Peace Racket’s influence will spread. And as it does, it will weaken freedom’s foundation’. With those health warnings in place I want to put my remarks into some sort of historical context. Students of the American Civil War may recognize the quote. It comes from President Lincoln’s first Inaugural Address: I am loath to close. We are not enemies but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may be strained it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriotic grave to every living hearth and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chains of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature. That speech was delivered on 4 March 1861. The first Battle of Bull Run occurred on 21 July and was the largest and bloodiest battle in the history of the U.S. up until that point. It led to a Confederate victory followed by the disorganized retreat of the Union forces when both sides came to realize that the war would be longer and more brutal than both sides had imagined. On the following day President Lincoln signed a Bill that provided for the enlistment of another 500,000 men for up to three years of service. Those bonds of affection were further stretched at the battle of Gettysburg (July 1-3, 1861) when between 46,000 -53,000 were killed, wounded or missing in action. The president’s response came on 19 November when he dedicated the National Cemetery in Gettysburg. As we all know the two minute long Gettysburg Address was an act of national redemption and serves as a classic example of memorialization in terms of site and speech (Wills, 1992). I want to pause here to suggest that both speeches are exemplars of establishing a national dialogue and a means of national redemption and were built on establishing relations of reciprocity and recognition, both of which have to be at the heart of conflict transformation. Recognition is a basic human need and reciprocity is the engine that enables reconciliation. They need each other. I want to celebrate the precise and uplifting use of the spoken word and to recognize its capacity to be a form of catharsis. On a personal level: I grew up in the wake of the Cuban Missile crisis – the nuclear cloud seemed to symbolize our destiny -, on Dr Martin Luther King’s civil rights movement and on the Vietnam War. My first public political act as a high school student was to march in protest against the Vietnam War. My most potent memory was Dr. King’s speech at the Lincoln Memorial which has a profoundly moving effect to this day. When we began our civil rights movement we attempted the equivalent of the Selma- Montgomery march. I recall the impact of all three of those marches. The first spurred President Johnston to push the Civil Rights Act through Congress. The second led to a speech by MLK which was a masterpiece of empathy and of political (and biblical) communication. When they finally reached their destination Dr. King acknowledged that their aim was not to defeat and humiliate the white man but rather ‘to win his friendship and understanding’ and to achieve a society ‘that can live with its conscience’. He then asked rhetorically four times how long it would take: … however frustrating the hour it will not be long because truth pressed to the earth will rise again. … not long because no lie can live forever … not long because you shall reap what you sow … not long because the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends towards justice. And the third march? That was ours between Belfast and Derry that is between Northern Ireland’s capital and what was considered to be the capital of discrimination by the unionist government against the Catholic minority (but majority in that city). We reached our destination but the price we paid was the descent into an intense violence that lasted three decades. We had not absorbed the lessons MLK had propounded in his “Letter from Birmingham Jail”. But I want to suggest, too, that we need to avoid (to quote Burke again) ‘the degenerate fondness for tricking short cuts’ because what the President’s Inaugural Address does in retrospect is to suggest that memory may be discordant as well as mystic; and what the site in Gettysburg does is to highlight the whole question of memorialization. Memorialization and Memory To begin with the latter: memorialization serves many purposes and takes many forms. We can differentiate between constructed sites (museums, monuments etc.), found sites (such as killing fields, concentration camps) and activities such as parading in commemoration of specific historic events. In those respects it represents a ‘powerful arena of contested memory and the formation of new national, community and ethnic identities’ (Baxter 2005). That is what Gettysburg is meant to represent. On the other hand as Neil Ascherson (2004) points out it can be utilized and brutalized by totalitarian regimes and as monuments to the ‘victor’ at the expense of marginalized groups and ordinary citizens. And it can be gruesome: ‘In some of the Killing Field memorials in Cambodia, tour guides will assist visitors in digging up remains such as bone fragments and teeth. We could say that this example deals with the immediate aftermath of conflict to convey the ‘scale of the genocide … but does not generally engage in the analysis of the roots of the conflict or in efforts to hold perpetrators accountable. Memorialization raises another issue. The French scholar, Maurice Halbwachs, notes that the past is not conserved but is reconstructed and, hence, that collective memory is not a simple resurrection or a revival of the past, but is essentially a reconstruction of the past to function in the present. A contentious example of the reconstruction of the past has been the activity of parading in Northern Ireland. In 1995, for example, it has been calculated that there were circa 3,500 parades in what is known as the ‘marching season’ (roughly between Easter and September) in a territory no larger than that of Rhode Island or Delaware with loyalist outnumbering republican parades by about 9:1. The former were celebrating the victory of William of Orange at the battle of the Boyne on 12 July 1690. These parades were considered to complete a circle between the past and the present and thus make the future certain through the recurrent celebrations of martial heroes and military victories. In this context memory ‘becomes less a means of conserving a distinct lineal history than a generator of meaning’. So memory becomes a contested concept. Indeed it was a Nobel Laureate, Czeslaw Milosz, who asserted that ‘it is possible that there is no other memory than the memory of wounds’. In terms of intractable conflict Milosz may be closer to the mark than Lincoln and that is the line I intend to pursue. In the first place we should distinguish between the individual and the collective. A graphic example of the former is provided by Marie Smyth when she says that by simply asking the question ‘should we remember?’ implies a choice that is beyond some people’s experience: ‘Remembering is not an option – it is a daily torture, a voice inside the head that has no on/off switch and no volume control’. Collectivities on the other hand, can choose (as we shall later) what is remembered and what is forgotten. We need, too, to distinguish between official and unofficial memory, between post memory and anticipatory memory. Again, I will revert to an example from the Northern Ireland conflict -Bloody Sunday when British paratroopers killed 14 civil rights’ marchers. The British government’s response was to create an officiaL narrative through the creation of the Widgery Tribunal. Lord Widgery was the most senior judicial officer in the UK at the time that he produced his Report in 1972. The families of those who had been killed and the wider catholic community considered his report a complete distortion of the facts and, in many ways, as big an affront as the actions on Bloody Sunday itself. That official position stood for 35 years until the Saville Inquiry reported. And one reason why there was that second enquiry was that a counter or anthropological memory in the shape of the Bloody Sunday Initiative which has been described as ‘an extraordinarily subtle regenerative and potent politics of memory’. By challenging the official narrative for so long it crossed generations and involved some who had not even been born when Bloody Sunday happened. They exemplified postmemory that characterized ‘the experience of those who grew up dominated by narratives that preceded their birth … the stories of a previous generation’. Here we are following Hirsch’s work on Holocaust families whereas Bloody Sunday was experienced less as ‘a burden than as a largely positive identification with a living, current struggle for peace, truth and justice’. That takes us to the fourth category developed by the philosopher, Richard Kearney, when he writes of the Irish republican project developing ‘an anticipatory memory capable of projecting future images of liberation drawn from the past’. It is millenarian and has become part of the struggle in the post-conflict era in Northern Ireland: What matters is not what happened but how it is remembered. And that precisely is what the IRA is now fighting for. Its struggle is for the control of the Northern Ireland conflict. Its Weapons are lies, evasions and strategic ambiguities. Its aim is to reshape the memory into … the afterglow of a glorious struggle for liberation. (O’Toole). Evasion and ambiguity remind us that historical trauma can be appropriated for political purposes. Evasion can take the form of erasure, for example, the Irish famine of the 1840s where the Irish considered it expedient to lay all the blame at the feet of the British rather than accept that some of their own had benefitted from the disaster . The evolution of modern Israel provides a fascinating case of forgetting and remembering. One aspect of it is caught in Amos Oz’s memoir: “Anyway, our faces here are turned towards the future, not the past, and if we do rake up the past we have enough uplifting Hebrew history from biblical times and the Hashmoneans”. Idith Zertal looks at more recent Israeli history to detect a change in Israeli society in the years of the capture and trial of Adolf Eichmann (196062) in which a process begins that replaces the silence and denial regarding the Holocaust. She remarks that in a 220 page textbook of Jewish history published in 1948, one page was devoted to the Holocaust compared to ten pages devoted to the Napoleonic wars. A Holocaust Remembrance Day became mandatory in 1959 but was not accepted universally. It was the Eichmann trial that changed the face of Israel psychologically and revolutionized Israeli’s self-perception. She carefully traces this growth in the ideological weight of the Holocaust for internal Israeli politics, beginning with Ben Gurion, that was not challenged adequately until an article by a survivor of Auschwitz appeared in Haaretz in 1988. Remembering and forgetting (although more of the latter) has been a feature of European politics in many of the decades following the end of the Second World War. It is one of the major themes that runs through Tony Judt’s magisterial PostWar. It is what Neil Ascherson has described as a continental amnesia which ‘became one of Europe’s attractions. Not a few nations wanted to ‘escape out of history and into Europe … Only in the 1960s when that amnesia had done its healing work (at least, for the compromised postwar political classes), did a revision of history begin to break through’. One strategy has been that of “knowing forgetting” (as a form of remembering) so that we may not be weighed down utterly by the burden of the past. Bonhoeffer (1997) goes so far as to speak of the capacity to forget as a form of grace. Equally it has to be remembered that failure to remember can impose unacceptable costs in ethical terms if we ignore collective injustice and cruelty which may indeed stroke fires of resentment and vengeance. To finish this section I want to suggest that in following the chain of memory we need to acknowledge that truth-telling, justice seeking and reconciliation are inherently political processes heavily influenced by conflicting interests and access to resources so that ‘… in designing transitional justice mechanisms, policymakers and practitioners engage in a complex moral calculus unguided by scientific principles yielding definitive proof of their ultimate benefits or harms’. Transcendence The scales are weighted towards the memory of wounds. In her study of Hegel and Heidegger, Edith Wyschogrod has described the C20 as the century of man-made mass death. In contemplating the new millennium the historian, Tony Judt, has argued that the role of the public intellectual will not be to imagine better worlds but to prevent worse ones. In his Nobel Address. Crediting Poetry (1995) the poet, Seamus Heaney remarked that it is difficult at times to repress the thought that history is as instructive as an abattoir; that Tacitus was right and that peace is merely the desolation left behind after the decisive operations of merciless power … Only the very stupid or the very deprived can any longer help knowing that the documents of civilization have been written in blood and tears, blood and tears no less real for being remote. And when this intellectual predisposition coexists with the actualities of Ulster and Israel and Bosnia and Rwanda, and a host of other wounded spots on the face of the earth, the inclination is not only not to credit human nature with much constructive potential but not to credit anything too positive in the work of art. Given that evidence it might be difficult to finish on a positive note but I will cite two reasons (one of which I cannot expand on today). That is the development of a Lex Pacificatoria or Law of the Peacemakers; and the other the power of the human spirit summarized for me by Bonhoeffer: ‘The essence of optimism is that it takes no account of the present, but it is a source of inspiration, of vitality and hope, where others have resigned; it enables a man to hold his head high, to claim the future for himself ..’. And if I look for a link between the Law of the Peacemakers and the spirit of optimism I read it into Anwar Sadat’s address to the Knesset in 1977 when he said “Peace is not a mere endorsement of written lines. Rather it is a rewriting of history’. I have lived and worked through the conflict in Ireland and have visited quite a few other conflict spots and two factors have been consistent in all of them. One is a deep sense of fatalism that is an incredibly negative impulse; and the other which complements that is a belief that “our” conflict is sui generis. Wnen you can demonstrate that there are commonalities and that we can learn one from another you have made the first step in sloughing off fatalism. There are heroic examples in all conflicts of citizen peace-building and of the power of transcendence, what Byron Bland has described as ‘connecting what violence has severed’. I will finish with one citation and it comes from the man who was full of despair a moment ago and who personifies the power of story-telling. Heaney recites a particularly horrific event when ten workmen returning home on a dark winter’s night were held up by a gang of gunmen who wanted to know if there were any Catholics among them. As it was there was only one and as he stepped out to identify himself his protestant neighbor touched his hand as if to console him that his comrades would protect him. The assumption was that the gunmen wanted to kill all Catholics. In fact they were IRA men and it was the nine Protestants who were gunned to death. The lesson that Heaney imparts was that ‘the birth of the future we desire, is surely in the contraction which that terrified Catholic felt on the roadside when another hand gripped his hand –not in the gunfire that followed, so absolute and so desolate. It is also so much part of the music of what happens’. That was an act of transcendence that impacted on the transmigration to follow. Heaney’s ‘birth of the future’ was to be delivered in 1998 when the Belfast Agreement was signed. It is no accident that I finish as I began by quoting a poet because I am concerned with language. It was Shelley in his A Defence of Poetry (1821) who described poets as the unacknowledged legislators of the world. He argued that the invention of language reveals a human impulse to reproduce the rhythmic and ordered, so that harmony and unity are delighted in wherever they are found and incorporated instinctively into creative activities. A peace process need not necessarily be a catalogue of the big public events of reconciliation and summits and photo opportunities. It is the small acts of transcendence and our capacity for reciprocity and recognition that underlines our common humanity that leads us towards these creative activities.