Unit III final paper

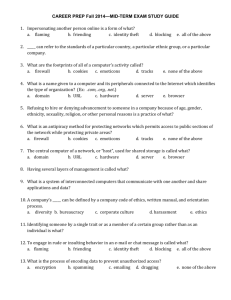

advertisement

Corinne Napper UNIV 112 Unit III Final Paper Sexual Harassment and Our Psychology Introduction: Sexual harassment has been a festering plague on our workforce for far too long, and it has left millions of employees asking the same question for many years: why does sexual harassment occur so often in the workplace? Studies show that the human psychological response to an abundance of power and control makes a person more likely to become abusive due to a lack of apparent consequences, therefor employees in high positions of their workplace are incredibly likely to harass the employees in lower positions, which is often how sexual harassment occurs. This could potentially be avoided if the federal government passes a law under the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission that mandates sexual harassment training with an emphasis on the psychological causes and effects of sexual harassment and the empowerment of victims and the rights of lower-level employees in order to create a more equal work environment. Socialized Fear of Reporting Sexual Harassment (Circumstance): The majority of sexual harassment in the workplace goes unreported, but why is this? The Washington Post released a poll regarding the issue recently, asking 500 randomly selected individuals about their experience with sexual harassment (Langer). One in four women polled said they had experienced sexual harassment while one in ten men said the same, so it is evident that sexual harassment is on the rise, but, interestingly enough, four out of ten sexual harassment victims stated that they did not report their case because they felt like it would either be ignored or negatively handled in their workplace (Langer). It is likely that the numbers indicated in this poll are actually higher considering a large portion of victims refuse to discuss their experiences at all, nonetheless with strangers on the telephone. It very often occurs that victims have been sexually harassed by their boss and are too frightened by the potential professional consequences that might befall them if they report someone of a higher status. These consequences date back to the very first sexual harassment complaint, filed by Lella Smith Candea, that resulted in her losing her office, getting demoted, and losing all office privileges in less than twenty-four hours of the complaint being processed (Abramson). In a similar poll held by the Huffington Post, 21% of a random sample of 1000 working adults said that, while they had never experienced sexual harassment, they had witnessed it happening in their workplace (Berman). Only 33% of those individuals marked that they had reported the harassment (Berman). This is most likely the Bystander Effect at work, which is the human brain’s reaction to a stressful situation while in a crowd that tells the individual to stay out of the situation and let another person handle it. This effect can often be avoided, much like other psychological stress responses, by being aware of its existence and actively avoiding it (Cherry). We can accomplish this awareness through educational training. Reality of Problematic Thinking and its Impact (Consequence): Awareness of what causes sexual harassment and the psychological effects of it would lower the number of cases of sexual harassment in the workplace, while ignoring these effects will undoubtedly increase them. Currently, the societal norm of sexual harassment revolves around victim blaming. Victim-blaming and slut-shaming are extremely prominent on college campuses and in the workplace, and these attitudes are making cases harder to solve or simply keeping them from being reported in the first place (Vendituoli). For example, at the University of Connecticut, a police officer who was investigating a rape case allegedly said to a victim, “Women need to stop spreading their legs like peanut butter, or rape is going to keep happening until the cows come home” (Vendituoli). This attitude undoubtedly creates a fear in victims when they see that the very people who are supposed to be investigating their cases blatantly do not understand the horrible psychological effects that sexual harassment and assault has on a victim, and the way that it is forced upon them by people who hold power. Studies on Imbalance of Powers (Authority): The extreme and negative psychological effects that power without consequence has on a work environment was proven by Professor Zimbardo and the United States Office of Naval Research during the Stanford Prison Experiment. Over 70 people volunteered when the experiment began, but only 24 were chosen and were randomly assigned the position of either a guard or a prisoner in a fake prison, taking place inside Jordan Hall on Stanford’s Main Quad (Ratnesar). The prisoners had no power and lived for days in fear of the guards, who were told that they could do anything to the prisoners with no legal repercussions (Ratnesar). At first the guards were tentative, but once they realized that nothing bad could happen to them no matter what they did, they quickly began to torture the assigned prisoners including stripping them naked, beating them, and harassing them (Ratnesar). The experiments were shut down early in fear of the safety of the “prisoners” being threatened, and Zimbardo released a statement to the public about how the overly-unequal distribution of power in the workplace, and the absence of legal and professional consequences to lawbreakers, leads to severe and potentially unintentional abuse of power, considering that most of the “guards” severely regretted what they had done once the experiment was over and they were snapped out of the illusion (Ratnesar). What Exactly Is Sexual Harassment? (Definition) Many people still perceive sexual harassment in the traditional sense; only relying on evidence of unwanted physical touching while ignoring the debilitating psychological effects that it has on a person. That might have been acceptable in the 1950s, but by today’s standards and social normativity, sexual harassment includes verbal and emotional harassment as well. In Judith Havemann’s article, “Evaluating Sexual Harassment in the Workplace; Education on the Subject ‘A Low Priority’ Despite Survey Finding Widespread Complaints,” published in The Washington Post in 1988, she interviews Frederick A. Miller, president of Kaleel Jamison Associates, he says, “Sexual harassment is something that happens to women in the workplace that prevents them from reaching their full potential” (Havemann). This shows the changed mindset of what sexual harassment is perceived as in our society, emphasizing how people have begun to understand that the act might not be purely physical (Havemann). This is shown from a legal standpoint as well with the passing of Title IX. Before Title IX, catcalling and other verbally or emotionally aggressive behavior was often dismissed with a “boys will be boys” type of mindset, as was the norm at the time in our society (“Ten”). After Title IX, it was legally recognized that sexual harassment also involves psychological stress on the workplace from sexual harassment, making it clear that sexual harassment can be classified as anything that keeps any employee or student from reaching their full potential in the workplace (“Ten”). Seeing as some people still don’t understand what exactly sexual harassment is and hole very old views of how it should be handled, more educational seminars on the subject should be held in every workplace. Responsibility of All People in the Workplace (Value): Knowing that there could even be a slight chance to lessen the number of sexual harassment cases through education, if the federal government decides to ignore these facts and allow the number of cases to increase, it would be highly immoral on the grounds of gender equality and basic human rights. Every employee in the building shoulders the responsibility of lessening sexual harassment, and should they not report sexual harassment it could potentially damage the victim emotionally, professionally, and physically. According to section 703 of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, titled Unlawful Employment Practices, “to limit, segregate, or classify his employees or applicants for employment in any way which would deprive or tend to deprive any individual of employment opportunities or otherwise adversely affect his status as an employee, because of such individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or national origin (“Title”).” Title VII also states that any practice that causes any disparate impact on the individual based on ascribed characteristics is unlawful (“Title”). This is why we need a stronger grip on sexual harassment in the workplace, and should start by educating all workers on their rights and the consequences of their actions through mandatory training. Any person who argues that sexual harassment in the workplace is a non-issue clearly does not understand the debilitating consequences on the victim, not to mention the overall lowered moral of the workplace. The Psychological Harassment Information Association has linked sexual harassment to severe mental and physical health problems in victims (“Psychological”). They also state that in a poll taken by female flight attendants, the women who polled that they had been sexually harassed at work were three times as likely to rate their health very poorly (“Psychological”). There is substantial evidence as to why we should be more forceful about spreading education on the debilitating effects of sexual harassment, and no clean evidence against it. These debilitating psychological effects should not be ignored from a legal standpoint as they have often been in the past. Spreading Awareness in Sexual Harassment and Drunk Driving (Comparison): Compared to the way sexual harassment was perceived as recently as the 1970s, it is more commonly recognized as a negative in our society, and we can thank the spreading of education and awareness for that. “Groups such as the Women’s Christian Temperance Movement and labor activists worked to protect women from sexual harassment and coercion in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These efforts lessened in the 1920s as female workers were expected to know how to deal with sexual harassment on their own” (Reed). The psychological ideas that people had in the past contributed to the societal expectations of victims in the past, and still do (Reed). Recently, due to changing laws and news headlines about the negative effects of the issue, sexual harassment has been occurring less often. This is true for an abundance of social and legal issues. For example, Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) contributed to passing the 21 age minimum drinking age law, which a study by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration showed saved approximately 30,000 lives in 2011 and led to a significant decrease in drunk driving among teenagers, because understanding all of the negative legal and psychological effects of alcohol creates a more cautionary aversion almost automatically (“National”). Safety through education has proven to work time and time again. It is rare for someone to vocalize negative thoughts towards sexual harassment training, but when they do, they are CEOs. David Lewis, president of OperationsInc, an HR firm in Connecticut, has been leading sexual harassment seminars for almost two decades. He has gone on record to say, “Training is done for all employees, except the top person or top few people manage not to attend, whether because they’re too busy or because they feel it’s not something they need to attend” (Wilkie). This attitude is one often held by people in positions of power in the workplace who believe that it is not important to them because they have less of a chance of being harassed, but this view is incredibly selfish and does not contribute to the work environment as a whole. Lewis goes on to explain why this is detrimental to the work environment, “The source of harassment sometimes really has no idea that what they’re saying and doing is harassment. Most of them are just ignorant and insensitive to the fact that it’s not about you or your intent; it’s about the victim and their perception” (Wilkie). Conclusion: Raising awareness and educating people on the psychological causes and effects of sexual harassment in the workplace plays a vital role in lessening the number of cases. Our society often ignores sexual harassment’s psychological effects on victims and only seems to care about cases that involve physical harm to the victim, which occurs much less often. Relatively, the psychological causes of sexual harassment that the harasser undergoes re completely unmentioned because our society’s problem with victimblaming and slut-shaming is so large that it seems impossible to battle, but if the federal government broadly educates our workers through the EEOC, it is possible to change our society’s perception of sexual harassment even further than it already has. Works Cited Abramson, Joan. Old Boys--new Women: The Politics of Sex Discrimination. New York: Praeger, 1979. Print. Berman, Jillian. "Workplace Sexual Harassment Poll Finds Large Share Of Workers Suffer, Don't Report." The Huffington Post. TheHuffingtonPost.com, 27 Aug. 2013. Web. 9 Nov. 2014. Cherry, Kendra. "How to Overcome the Bystander Effect." About. About Education, n.d. Web. 19 Nov. 2014. Havemann, Judith. "Evaluating Sexual Harassment in the Workplace;Education on the Subject `a Low Priority' Despite Survey Finding Widespread Complaints." The Washington Post. N.p., 4 July 1988. Web. 10 Oct. 2014. Langer, Gary. "One in Four U.S. Women Reports Workplace Harassment."ABC News. ABC News Network, 16 Nov. 2011. Web. 01 Dec. 2014. "Psychological Harassment Information Association."Psychological Harassment Information Association. N.p., n.d. Web. 14 Nov. 2014. Ratnesar, Romesh. “The Menace Within.” Stanford Magazine. N.p., Aug. 2011. Web. 13 Nov. 2014 Reed, Amanda. "A Brief History of Sexual Harassment in the United States." National Organization for Women. N.p., n.d. Web. 16 Nov. 2014. "School-Based Programs to Prevent and Reduce Alcohol Use Among Youth." Alcohol Research & Health, Volume 34, Number 2. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, n.d. Web. 04 Dec. 2014. "Ten Key Areas of Title IX." TitleIX.info. The Margaret Fund, n.d. Web. 07 Dec. 2014. "Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964." Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, n.d. Web. 26 Nov. 2014. Vendituoli, Monica. "Funding Alone Can't Change How Sexual Assault Is Handled On Campus." FiveThirtyEight. N.p., 10 Nov. 2014. Web. 11 Nov. 2014.