US Imperialism: Post-Spanish-American War Analysis

advertisement

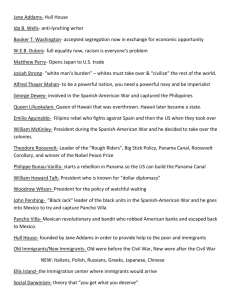

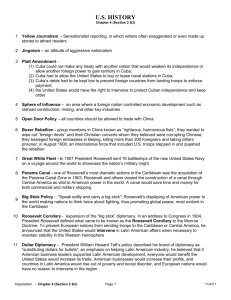

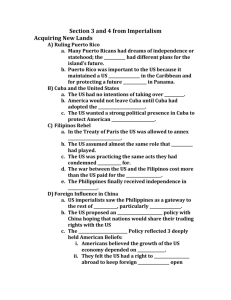

Reading 3 Post War The Role of America: Protector or Oppressor? After victory over the Spanish, the United States was placed in a somewhat uncomfortable position. It had criticized Spain for the way it had controlled Cuba, yet many in America did not want Cuba to be totally free either. The dilemma facing Americans after victory was one that would be rethought throughout the twentieth century: how to combine imperialistic intentions with the deep-seated American beliefs in liberty and self-government. Fearing that America would want to annex Cuba, supporters of Cuban independence in Congress had inserted the Teller Amendment in the original congressional bill calling for war against Spain. This amendment stated that America would not do this under any circumstances. Nevertheless, President McKinley authorized that the Cubans would be ruled by an American military government (which kept control until 1901). The military government did authorize the Cubans to draft a constitution in 1900 but also insisted that the Cubans agree to all of the provisions of the Platt Amendment. This document stated that Cuba could not enter into agreements with other countries without the approval of the United States, that the United States had the right to intervene in Cuban affairs "when necessary," and that America be given two naval bases on the Cuban mainland. The Platt Amendment remained in force in Cuba until the early 1930s. The Debate Over the Philippines The debate in America over what to do with the Philippines was a much more intense one. This debate took place on the floor of the Senate and in countless editorial pages across the country. An aggressive policy toward Cuba could be justified, since it was only 90 miles away and seemed important to the United States' position in the Western Hemisphere. Many had second thoughts, however, over controlling the Philippines; the Filipinos seemed a world away, and, after all, were not "like us." In addition, Americans became aware that Filipinos expected that after the Americans helped throw out the Spanish they would then help them achieve independence. What, indeed, should America's role in the Philippines be? All of the most basic arguments on the merits of imperialism were debated in the aftermath of the Spanish-American War. Didn't the concept of ruling a territory by force violate everything that America stood for? An Anti-Imperialist League was formed in 1898 (with Mark Twain and William Jennings Bryan as charter members). The first brochures put out by this organization wondered if America didn't have too many problems at home to be involved abroad, and also expressed the fear that the armies need for imperialistic adventures abroad might also be used to curb dissent at home. Others pointed to the huge costs of imperialism and the fear that natives from newly acquired territories might take the jobs (or lower the wages) of American workers. Some pointed out the basic racism involved in American attitudes toward the Filipinos; some Southerners opposed imperialism because they feared it would bring people of the "inferior races" to America in greater numbers. In the end, those arguing the political, strategic, and economic advantages that control of the Philippines would bring won the national argument. The American frontier was closing; wouldn't expansion abroad keep America vital and strong? In addition, religious figures noted that the acquisition of the Philippines would give the church the opportunity to convert Filipinos to Christianity. In the end, President McKinley supported American control of the Philippines, stating that if the Americans didn't enter, civil war was likely there. He also proclaimed that the Filipinos were simply "unfit for self-government." The treaty authorizing American control of the Philippines was ratified in February of 1899. It should be noted that American soldiers fought Filipino rebels for the next three years, with nearly 4500 American soldiers killed in this fighting. The American army attacked Filipino rebels with a vengeance; by the end of the insurrection, 200,000 Filipinos had been killed. Many humanitarian groups in America, which had initially enthusiastically supported the Spanish-American War, were appalled. An American commission later criticized the U.S. military for its conduct when dealing with the rebel forces. Connecting the Pacific and the Atlantic: The Panama Canal After the Spanish-American War, most in America and in Europe regarded America as one of the major world powers. Theodore Roosevelt became president after the assassination of President McKinley and, as he had previously demonstrated, favored an aggressive foreign policy. (McKinley was killed during the first year of his second term as president by an anarchist; the next day, political boss Mark Hanna lamented "now that damned cowboy is President of the United States.") One of Roosevelt's most cherished goals was the construction of the Panama Canal, which would link the Pacific and the Atlantic Oceans. The strategic and economic benefits of such a canal for America at the time were obvious. A French building company had already acquired the rights to build such a canal in the region of Panama (which was controlled by Colombia). In 1902, the United States bought the rights from the company to construct the land, but this agreement was opposed by the Colombians. A "revolt" was organized in Panama by the French. United States warships sailed off the coast of Panama to help the "rebels." The United States was the first to recognize Panama as an independent country; newly installed Panamanian officials then gave America territory to build a canal. By the terms of the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty of 1904, the United States received permanent rights and sovereignty over a 10-mile-wide area on which they planned to build the canal. In return, Panama was given $10 million. Construction of the canal began shortly afterward. In the United States, there was much criticism of American actions in Panama, but as in the case of the Philippines, the practical benefits of having a canal won out. The canal was finally completed in 1914. American businesses could now ship their goods faster and cheaper, although the acquisition of the Panama Canal deepened the suspicion of many in Latin America toward the United States. The Roosevelt Corollary Theodore Roosevelt's most famous quote was to "speak softly and carry a big stick." In 1904, he also announced the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine to Congress, which stated that the United States had the right to intervene in any country in the Western Hemisphere that did things "harmful to the United States," or if the threat of intervention by countries outside the hemisphere was present. The Roosevelt Corollary strengthened American control over Latin America, justified numerous American interventions in Latin American affairs in the twentieth century, and increased the "Yankee go home" sentiment throughout the region. In Santo Domingo (now the Dominican Republic), the government went bankrupt, and European countries threatened to intervene to collect their money; under the provisions of the Roosevelt Corollary, Roosevelt organized the American payment of Santo Domingan debt to keep the Europeans out. In fairness, it should also be noted that Roosevelt won the Nobel Peace Prize for his mediation between the Japanese and the Russians after the Russo-Japanese War of 1904. William Howard Taft, Roosevelt's successor, was not as aggressive in foreign policy as Roosevelt. He favored "dollars over bullets" and instituted a policy labeled by his critics as "Dollar Diplomacy," which stated that American investment abroad would ensure stability and good relations between America and nations abroad. This policy would also be hotly debated throughout the twentieth century.