JMoth@aol.com

jeanniemotherwell.com

Joy Street Studios, 86 Joy Street, Studio 4, Somerville, MA 02143

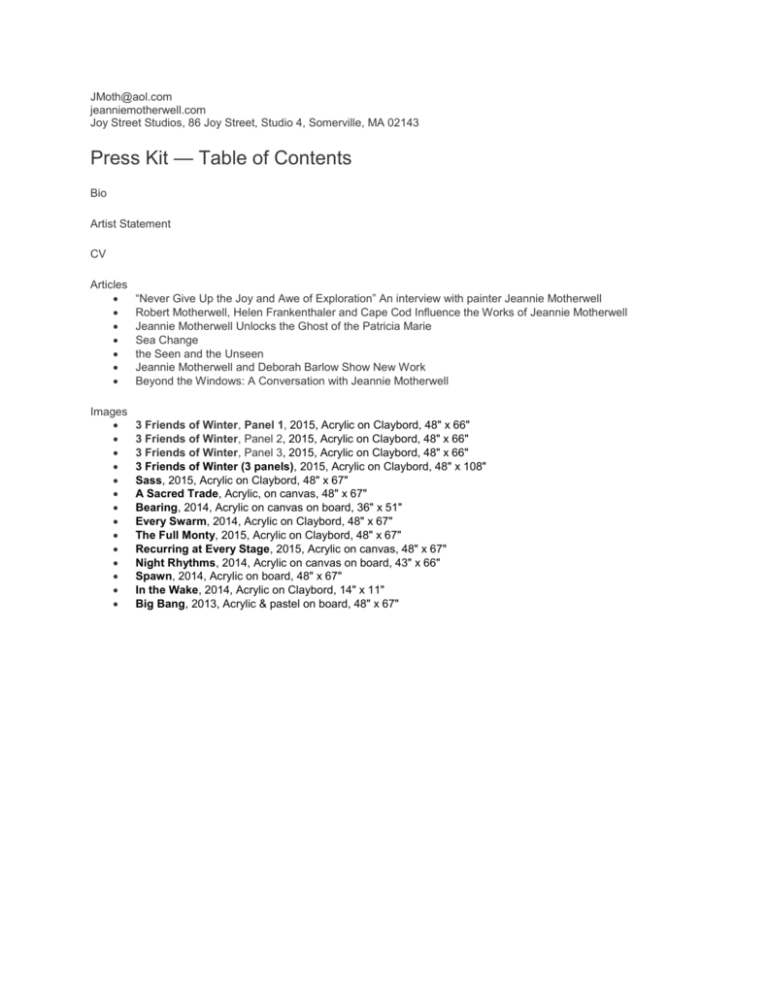

Press Kit — Table of Contents

Bio

Artist Statement

CV

Articles

“Never Give Up the Joy and Awe of Exploration” An interview with painter Jeannie Motherwell

Robert Motherwell, Helen Frankenthaler and Cape Cod Influence the Works of Jeannie Motherwell

Jeannie Motherwell Unlocks the Ghost of the Patricia Marie

Sea Change

the Seen and the Unseen

Jeannie Motherwell and Deborah Barlow Show New Work

Beyond the Windows: A Conversation with Jeannie Motherwell

Images

3 Friends of Winter, Panel 1, 2015, Acrylic on Claybord, 48" x 66"

3 Friends of Winter, Panel 2, 2015, Acrylic on Claybord, 48" x 66"

3 Friends of Winter, Panel 3, 2015, Acrylic on Claybord, 48" x 66"

3 Friends of Winter (3 panels), 2015, Acrylic on Claybord, 48" x 108"

Sass, 2015, Acrylic on Claybord, 48" x 67"

A Sacred Trade, Acrylic, on canvas, 48" x 67"

Bearing, 2014, Acrylic on canvas on board, 36" x 51"

Every Swarm, 2014, Acrylic on Claybord, 48" x 67"

The Full Monty, 2015, Acrylic on Claybord, 48" x 67"

Recurring at Every Stage, 2015, Acrylic on canvas, 48" x 67"

Night Rhythms, 2014, Acrylic on canvas on board, 43" x 66"

Spawn, 2014, Acrylic on board, 48" x 67"

In the Wake, 2014, Acrylic on Claybord, 14" x 11"

Big Bang, 2013, Acrylic & pastel on board, 48" x 67"

JMoth@aol.com

jeanniemotherwell.com

Joy Street Studios, 86 Joy Street, Studio 4, Somerville, MA 02143

Jeannie Motherwell

Bio

Born and raised in New York City, Jeannie Motherwell grew up in a home fully invested in Abstract Expressionism

and color field painting; her father Robert Motherwell and stepmother Helen Frankenthaler were pillars of that milieu.

She studied painting at Bard College and the Art Students League in New York. In the late 1970's, in Provincetown

MA, Jeannie found her own voice as a painter in a series of paintings and collages entitled 'Patricia Marie,' about a

local fishing boat whose entire crew perished when it sank. Jeannie had become friendly with many of the crew while

spending two winters in Provincetown.

In 1990 Jeannie moved to CT, to be closer to her father and to raise her daughter Rebecca. There, she became

active in arts education at the Bruce Museum in Greenwich, CT, developing programs for students ages 4 - 18. In

1998 she relocated to Cambridge, MA. From 2002 - 2015 she worked at Boston University for the Graduate Program

in Arts Administration. She also served on the Public Art Commission Advisory Committee for the Cambridge Arts

Council (2004 - 2007).

Her work has been featured in such publications as Hamptons Cottages and Gardens, Avenue, Home & Design,

and Provincetown Magazine. Her work is in public and private collections throughout the US and abroad, including

the permanent collection of the Provincetown Art Association and Museum (PAAM).

Jeannie is represented by Lynne Scalo in Greenwich, CT.

JMoth@aol.com

jeanniemotherwell.com

Joy Street Studios, 86 Joy Street, Studio 4, Somerville, MA 02143

Jeannie Motherwell

Artist Statement

I am constantly amazed with the images and mysteries of creation – oceans and skies in changing weather, Hubbletype images of the universe, and my own physicality during the painting process. It is the space in these images that I

seek to capture and the 3-dimensional energy that defines that space. This requires special appreciation for the

edges of the picture so that, rather than the eye moving off the surface, it bounces back to go through the surface.

Pouring, pushing, and layering paint unfolds those mysteries of creation and further informs me of my own space and

role within it.

Though I begin with intention, the process itself yields marvelous surprises that carry me in directions I have not

anticipated. It is like a dance with a creative partner gently leading me into moves I have not yet experienced.

617.216.1525

JMoth@aol.com

jeanniemotherwell.com

Joy Street Studios, 86 Joy Street, Studio 4, Somerville, MA 02143

Jeannie Motherwell

CV

EDUCATION

1976

1974

The Art Students League of New York, Painting

Bard College, BA, Painting

SOLO and TWO-PERSON EXHIBITIONS

2014-present Lynne Scalo Design New Paintings

Lynne Scalo Design New Paintings

2013-2014

Greater Boston Vineyard New Paintings

Lyman-Eyer Gallery New Work: Far Out 2009-2011

2011

Boston University, Metropolitan Gallery Paintings and collages 2004-2010

2010

Cadbury Commons Art Gallery Sea Change

Lyman-Eyer Gallery New Paintings

2009

CVS Gallery Paintings and Collages

2008

2007

2006

2005

2004

2003

2002

2001

2000

1999

1981

1978

1974

Greater Boston Vineyard NoCa All Arts Open Studios

Lyman-Eyer Gallery New Paintings

Boston University, Metropolitan Gallery

Vineyard Christian Fellowship of Cambridge

Lyman-Eyer Gallery Abstracted landscapes

Lyman-Eyer Gallery New work

Lyman-Eyer Gallery Recent abstract landscapes

Lyman-Eyer Gallery Recent work

Lyman-Eyer Gallery Recent work

Lyman-Eyer Gallery Winter Salon Series

Boathouse Gallery

Boathouse Gallery

Hunneman Realty Art Gallery

Cambridge Public Library

Charles & Associates

Provincetown Group Gallery

Provincetown Group Gallery Patricia Marie Series

Bard College

GROUP EXHIBITIONS

Via Garibaldi 1791 ArtVenice Biennale 3

2015

Somerville Museum Artists' Choice

Greenwich, CT

Westport, CT

Cambridge, MA

Provincetown, MA

Cambridge, MA

Cambridge, MA

Provincetown, MA

Porter Square,

Cambridge, MA

Cambridge, MA

Provincetown, MA

Boston, MA

Cambridge, MA

Provincetown, MA

Provincetown, MA

Provincetown, MA

Provincetown, MA

Provincetown, MA

Boston, MA

Provincetown, MA

Provincetown, MA

Cambridge, MA

Cambridge, MA

Cambridge, MA

Provincetown, MA

Provincetown, MA

Annandale-on-Hudson, NY

Venice, Italy

Somerville, MA

GROUP EXHIBITIONS (continued)

Joy Street Studios — Tenth Anniversary Open Studios

2014

Atlantic Works Gallery Boston Biennial 3*

Joy Street Studios Somerville Open Studios

Artist's Choice Somerville Museum

Brickbottom Gallery Chain Reaction

2013

Antiques & Art Avant-Garde Greenwich A fundraiser for the Bruce Museum and

2012

Greenwich Historical Society

Lyman-Eyer Gallery New Work in conjunction with Robert Motherwell: Beside the

Sea, Provincetown Art Association and Museum

Acme Fine Art Provincetown Views

Fay Chandler Gallery 10th Annual Small Works

2010

Greater Boston Vineyard Cambridge Open Studios North/West — Far Out: SpaceTime

Cambridge Arts Council Gallery Cambridge Open Studios Salon Preview

Exhibition

Greater Boston Vineyard Rivers

Provincetown Art Association and Museum (PAAM) Generations Exhibition

2009

Maud Morgan Visual Arts Center, Sacramento St. Gallery Small Works 2009

Massport, Logan Airport Cambridge Open Studios

WGBH The 2009 WGBH Auction

Lydia Fair at Greater Boston Vineyard NoCa All Arts Open Studios

Hope Fellowship Church 5th Annual Visual Arts Festival

Maud Morgan Visual Arts Center, Sacramento St. Gallery Small Works 2008

2008

Lyman-Eyer Gallery Summer Salon, Recent work

Hope Fellowship Church 4th Annual Visual Arts Festival

Maud Morgan Visual Arts Center, Sacramento St. Gallery 7th Annual Small

2007

Works

Maud Morgan Visual Arts Center, Sacramento St. Gallery 6th Annual Small

2006

Works

Vineyard Christian Fellowship of Cambridge NoCa All Arts Open Studios

2005 - 2006 Lyman-Eyer Gallery Winter Salon

Maud Morgan Visual Arts Center, Sacramento St. Gallery 5th Annual Small

2005

Works

NoCa All Arts Open Studios

Newton Free Library Rock, Paper, Scissors

Maud Morgan Visual Arts Center, Sacramento St. Gallery 4th Annual Small

2004

Works

Fall Arts Festival, Lyman-Eyer Gallery Provincetown Painters — The Ties That

Bind Us

Lyman-Eyer Gallery Spring Salon

The Atrium NoCa All Arts Open Studios

Coldwell Banker Art Gallery NoCa Arts group show

Monroe Center for the Arts Landscapes

2003

Maud Morgan Visual Arts Center, Sacramento St. Gallery 3rd Annual Small

Works

Art of July 10th Annual

Boston State House Exhibition NoCa Invitational: Travel

Stebbins Gallery Annual Open Juried Photography Show

The Atrium NoCa All Arts Open Studios

Jeannie Motherwell — CV

Somerville, MA

Boston, MA

Somerville, MA

Somerville, MA

Somerville, MA

Greenwich, CT

Provincetown, MA

Boston, MA

Cambridge, MA

Cambridge, MA

Cambridge, MA

Cambridge, MA

Provincetown, MA

Cambridge, MA

Boston, MA

Boston, MA

Cambridge, MA

Cambridge, MA

Cambridge, MA

Provincetown, MA

Cambridge, MA

Cambridge, MA

Cambridge, MA

Cambridge, MA

Provincetown, MA

Cambridge, MA

Cambridge, MA

Newton, MA

Cambridge, MA

Provincetown, MA

Provincetown, MA

Cambridge, MA

Cambridge, MA

Lexington, MA

Cambridge, MA

Boston, MA

Boston, MA

Cambridge, MA

Cambridge, MA

page 2

GROUP EXHIBITIONS (continued)

Color Stories, Inc. Competitive Exhibition

2003

(continued)

Maud Morgan Visual Arts Center, Sacramento St. Gallery 2nd Annual Small

2002

Works

New England School of Art & Design at Suffolk University Special 9/11

Exhibition and Event

TransCultural Coaster Project Destination: The World featuring 100 Artists Plus

Stebbins Gallery Annual Juried Photography Show, Paul Weiner, Juror

Lynn Arts Possibilities 2nd Annual Mixed Media

New England School of Art Digital City: New Squirts for Now People

Maud Morgan Visual Arts Center, Sacramento St. Gallery

NoCa: Art From a Cambridge Community

Lyman-Eyer Gallery Gallery Artists Ongoing

The Atrium NoCa All Arts Open Studios

Provincetown Art Association & Museum (PAAM) Members Juried

2001

Maud Morgan Visual Arts Center, Sacramento St. Gallery 1st Annual Small

Works

The Atrium NoCa All Arts Open Studios

Gallery 57 Cambridge Arts Council

2000

Provincetown Art Association & Museum (PAAM) National's Competition Finalist

The Atrium NoCa All Arts Open Studios

Mount Auburn Hospital Art for Life

DNA Gallery

1999

Provincetown Art Association & Museum (PAAM)

NoCa All Arts Open Studios

DNA Gallery

1998

NoCa All Arts Open Studios

Boston, MA

Cambridge, MA

Boston, MA

Boston, MA

Cambridge, MA

Lynn, MA

Boston, MA

Cambridge, MA

Boston, MA

Cambridge, MA

Provincetown, MA

Cambridge, MA

Cambridge, MA

Cambridge, MA

Provincetown, MA

Cambridge, MA

Cambridge, MA

Provincetown, MA

Provincetown, MA

Cambridge, MA

Provincetown, MA

Cambridge, MA

SELECTED PUBLICATIONS

"Tide No. 2," Home page of San Francisco Peace and Hope, downloaded April 24, 2015

2015

"Ebbing," masthead/cover of Art Connection, Fall/Winter, 2014

2014

San Francisco Peace and Hope "The Book", wrap around book jacket featuring "Tide 2"

"'One Thing and One Thing Only - To Paint'," interviewer: Kit Kennedy, San Francisco Peace and Hope,

Issue 4

"San Francisco Peace and Hope," sfpeaceandhope.com, Issue 4, Chapter 1

"Elementary" and "Circle of Life" in "Understated Elegance," Avenue, April, 2014

"Elementary" and "Circle of Life" in "Rooms with a View 2013," Quintessence, November 18, 2013

2013

"Dance" in "Holiday House Hamptons," Hamptons Cottages and Gardens, July 15, 2013

2012

"'Never Give Up the Joy and Awe of Exploration,' An interview with painter Jeannie Motherwell," interviewer: Kit

Kennedy, San Francisco Peace and Hope, Issue 3

River Run, Acrylic on canvas, San Francisco Peace and Hope, Issue 3, Chapter 1

Patricia Marie: Abyss, Acrylic & collage on canvas, San Francisco Peace and Hope, Spring / Fall Issues,

2012

"Robert Motherwell, Helen Frankenthaler and Cape Cod Influence the Works of Jeannie Motherwell," by

Jeannie Motherwell, Journal of the Print World, Vol. 35, Number 1, January, 2012

Jeannie Motherwell — CV

page 3

SELECTED PUBLICATIONS (continued)

"Dune with Dreams," Good Samaritan Medical Center, Emergency Department, audio guide

2011

"Jeannie Motherwell: New Work," by Jim Foritano, Artscope Magazine, July/August, 2011

"San Francisco Peace and Hope," sfpeaceandhope.com, Chapters 1 and 5

"Jeannie Motherwell — Paintings and Collages: 2004-2010," Boston University Metropolitan College, Winter,

2011 (Acrobat pdf file)

"The Provincetown Roots of Jeannie Motherwell," Provincetown Magazine, Vol. 32, Issue 15, July 23, 2009

2009

"Capsule Previews," artscope, New England's Culture Magazine, November/December, 2008 Expanded

2008

Year-End Issue

"Studio Show Recollections/Robert Motherwell," by Jeannie Motherwell, Provincetown Arts Magazine, Vol. 23,

annual issue, 2008/2009

"Robert and Jeannie Motherwell," Provincetown Art Guide, 2008 fifth anniversary edition

"Year In Review 2007," by Sue Harrison, Provincetown Banner, Vol. 13, Number 34, December 27, 2007

2007

"Gallery Scene," Provincetown Magazine, Vol. 30, Issue 18, August 9, 2007

"Administrator by Day, Artist by Night," by Rebecca McNamara, BU Today, August 8, 2007

"Jeannie Motherwell Unlocks the Ghost of the Patricia Marie," by Susan Rand Brown, Provincetown Banner,

August 2, 2007

"Patricia Marie," Provincetown Magazine, Vol. 30, Issue 17, August 2, 2007

"Artists: Art Talk," Provincetown Arts Magazine, Vol. 19, annual issue, 2007-2008

"on display at the MET Gallery," Boston University Metropolitan College, commencement 2007

"Jeannie Motherwell & Friends @ Lyman-Eyer," Provincetown Magazine, Vol. 29, Issue 21, August 31, 2006

2006

"Making a Bid," Boston Globe 'Sidekick,' July 27, 2006

"Sea Change," American Airlines 'American Way,' December 1, 2005

2005

"Around P'town," Provincetown Banner and Advocate, July 30, 2005

"Open Studios: Art in Context," by Kristin Lambert, artsMEDIA Magazine, May/June, 2005

"Artists: Art Talk," Provincetown Arts Magazine, Vol. 18, annual issue, 2004/2005

"Faculty artwork," Boston University Metropolitan College, Winter 2005

"Weld, Click, Rip: Three North Cambridge Artists join forces for an exhibit," by Chris Helms, Chronicle Staff,

Cambridge Chronicle, January 6, 2005

2004

2002

2001

2000

1999

1980

"The Seen and the Unseen, Jeannie Motherwell and Deborah Barlow Show New Work," by Brenner Thomas,

Editor, Provincetown Magazine, Vol. 27, Issue 12, June 24-30, 2004

"On Display: Jeannie Motherwell Works on Paper," Life In Provincetown, Vol. 3, Issue 9, June 24, 2004

"Finding the Light: Artist's Statements," by Stuard Derrick, Provincetown Magazine, Vol. 25, Issue 25

(September 19–25, 2002)

A Sense of Place by Gillian Drake

"The Gallery Scene," Cape Arts Review

"Art Talk," Provincetown Arts Magazine (Provincetown)

"Portrait of an Artist: Jeannie Motherwell," by Stuard Derrick, Provincetown Magazine Vol. 25, Issue 18,

August 1-7, 2002 (Provincetown)

"Open Studios Offers Artists, Public A Chance To Interact," Cambridge Chronicle (Cambridge)

"Peek Behind the Painting," by David Ortiz, Cambridge Tab, April 26

On Equal Ground: Photographs from an Artist's Community by Norma Holt, Provincetown Art Association &

Museum (PAAM), 2001

artsMEDIA Magazine, Summer Issue

"Jeannie Motherwell: Painting Again," by Dan Cooper, P'town Women Magazine (Provincetown)

"Beyond the Windows: A Conversation with Jeannie Motherwell," by Peter Alson, Provincetown Arts

Magazine (Provincetown)

"Works in Progress," The Cambridge Tab (Cambridge)

Face of the Artist: Photographs by Norma Holt through Provincetown Art Association & Museum (PAAM)

Exhibition, July 1980

Jeannie Motherwell — CV

page 4

RECOGNITIONS AND COMMISSIONS

Brooklyn Waterfront Artists Coalition, Black & White 2015; Juror: Christiane Paul, Curator of New Media

2015

Arts, Whitney Museum of American Art; New York, NY

Eclipse. Private collection. Commission.

2014

The Art Connection Artist of the Week

2013

REACH Auction REACH Beyond Domestic Violence (Refuge. Education. Advocacy. CHange.)

2011-2013

Corporate Art Loan Program deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum

2009 current

Home Is Where The Art Is Children's Hospital Boston

2009

Lydia Fair Producers Circle Greater Boston Vineyard

2009

Advisory Board Cambridge Open Studios (COS)

2008

2003 - 2007 Public Art Commission Advisory Committee Cambridge Arts Council

Monroe Center for the Arts, Competitive Landscape Exhibition Juror: Jeannie Motherwell

2003

Stebbins Gallery, Cambridge, Best In Show, Annual Open Juried Photography Show Paul Weiner, Juror

2002

Provincetown Art Association & Museum (PAAM) National's Competition Finalist

2000

Jeannie Motherwell — CV

page 5

interviewer: Kit Kennedy

San Francisco Peace and Hope, Issue 3, 2013 — http://www.sfpeaceandhope.com/issue3/jminterview.html

“NEVER GIVE UP THE JOY AND AWE OF EXPLORATION”

An interview with painter Jeannie Motherwell

Recently Kit Kennedy caught up with celebrated Cambridge (MA)-based painter and arts administrator, Jeannie

Motherwell whose work appears in San Francisco Peace and Hope. You can see “Perfect Storm” in chapter 1 of the

current issue.

Kit Kennedy: You come from a veritable art family (father, Robert Motherwell; stepmother, Helen Frankenthaler).

Your dad said, “You have talent and the bug.” Your parents pinned your drawings on the refrigerator and framed your

art. When did you know you were an artist?

Jeannie Motherwell: My interest initially developed in high school where I had a wonderful art teacher. But I took my

art more seriously when I went to Bard College and majored in painting. My father and I had just returned from a trip

to Europe. We had numerous discussions about art and I was very excited about studying in an art department where

all the professors were internationally known artists exhibiting in the now “happening” Soho. When I began painting at

Bard, I found myself writing letters to (and calling) my father describing the feelings I had while painting or

contemplating various challenges in my work. The feeling of elation I received from painting was like continually falling

in love.

KK: Do you still get that feeling of falling in love when you paint?

JM: Of course! One ages, but yes, it still holds true for me. When I finish a painting and I learn something I did not

know before, I fall in love with the picture.

KK: What inspires you?

JM: In Provincetown, the beach, light and the moment-by-moment way the sea changes. I no longer have a

Provincetown studio so I have had to re-create my inspiration. These days, poetry and collage, the celestial bodies

and what is happening in outer space inspire me. My new work seems to be incorporating inspirations from

both my recollections of the view from my Provincetown studio and the celestial series of paintings I recently

completed. I love how they are connecting earth and sky.

KK: Collage and poetry — That’s of interest to the SF Peace and Hope poetry community. Please elaborate.

JM: The poetry in my collages has mostly been taken from poet friends of mine. Many attended college with me,

majored in poetry and still write today. I think there are one or two earlier collages that have Rilke — when my

daughter, who also attended Bard, was experiencing her first love.

KK: How do you keep yourself motivated; your art fresh? How do discipline and deadlines play out in your life?

JM: It is always more helpful to have deadlines as motivation, but when that is not the case, I know showing up in my

studio is half the battle. Even if I don’t feel like going there some evening, I meander there anyway; eventually things

begin to happen, I see something that needs to be altered, or I begin a new painting, and then I get into the rhythm of

my painting. If I don’t show up, obviously nothing will happen.

KK: When do you know you have a “keeper?”

JM: When I see something that totally surprises me and it hits me in the gut. It’s like an “aha moment” or it could be

described as a lucky accident. There are no certainties in painting, but you have to keep yourself open to new ideas,

while pushing your limits. The only thing I want to control is when I know something about the picture is wrong…so I

make a correction. Rarely do I throw out a painting. I am usually able to revive it from drastic mistakes. But I am on a

constant journey and when I am lucky, I discover amazing things about the dynamics of any given work.

KK: Please describe one of your lucky accidents.

JM: The other night I was working on a large painting on the floor. It was too wet to lean it against a wall so I could

see how it was working. But I had a feeling it would be a good picture. Once it was dry, I leaned it against the wall and

thought it was a pretty good beginning. Then I turned it upside down and it hit me in an instant that this is the way the

painting is going to go, from now on, until it is finished.

Jeannie Motherwell — “NEVER GIVE UP THE JOY AND AWE OF EXPLORATION”

Page 2

KK: In an interview you mentioned that black is your favorite color. Is that still true? Has your palette changed?

JM: Black has always been a favorite color of mine because I try to use it in so many ways — mostly as a color vs. a

mood or darkness or depth. In recent years my palette has been very much influenced by the sea and the sky and the

earth. But black is a “go to” color for me and I often resort to it when I am unsure of what color to use instead.

KK: When do you know your painting is finished?

JM: I usually have a direction of where I’m going. But sometimes the unexpected happens. Every once in a while, I

feel a complete lack of control, and there’s a spark that really excites me — that’s my fodder. I know I need to

relinquish control so I don’t lose the innocence of the picture.

KK: When you’re not art-making what engages you?

JM: I work full time at Boston University for a graduate program in arts administration. I work with two other artists,

one visual, the other, a musician. Our goal is to help students understand how to “make the world safe for art — not

making art safe for the world.” The artist shouldn’t feel creatively restrained. In theory, there are no limits to art.

KK: How has your 9-5 influenced your art?

JM: I don’t think I could work a 9-5 job if it weren’t involved in the arts in some way. I feel our program is giving our

students experience and tools they need to become good arts managers in both the visual and performing arts

sectors. That said, it is certainly a challenge to transition from my day job to entering my studio at night. The discipline

of showing up each night in my studio gives me fodder for why I do what I do during the day.

KK: When you go to your studio, how do you ready yourself for the night’s work?

JM: Before I paint, I need to get really loose and not think too much. Basically, I blast rock music. When I realize it’s

late and I’m probably disturbing our neighbors, I shut down for the night.

KK: When someone who doesn’t know you looks at your art, what do they know about you?

JM: I guess it would depend on how much they know about painting in general. But depending on which body of work

they are looking at, they might think I am serious and pondering, or drenched in exploration of space, color and

energy. It’s a curious question, because I’ve never really thought about it. I just want people to get engaged when

they look at my work. I’m sometimes told that it takes a while to take them in. There is more than meets the eye, I

hope. I would like to think they are contemplative in some way. I want my paintings and their surfaces to look easy

and fresh but ultimately they are more complicated than that.

KK: What advice do you have for emerging artists?

JM: The art world is an ever changing and fast paced enterprise. Study hard, paint a lot, and never give up the joy

Jeannie Motherwell — “NEVER GIVE UP THE JOY AND AWE OF EXPLORATION”

Page 3

and awe of exploration. Do it for yourself, but also give back to the world in some way.

KK: In a 1976 interview you talked about Bobby, a dark-haired fisherman who perished on the Patricia-Marie boat too

full of scallops making its trip back to Provincetown. Thirty years later, you commented that when painting abstracts

the Patricia-Marie tragedy was “a pivotal memory for me.” Please comment.

JM: When I began painting in college, I learned a lot from my professors. Clearly, I had also gathered a wealth of

knowledge from Helen and my father. But it wasn’t until a couple of years post graduation, that I decided to spend

two winters in Provincetown, Massachusetts, where I had a studio on the bay. I had summered every year there, so it

was a natural haven for me to find out what I was made of. The first winter I was there, a tragic accident occurred with

one of the local fishing boats. I was friendly with several of its crew, all of whom perished. The morning before the

(Patricia Marie) boat sank, I was riding my bike through town on my way to do the bike trails – one of my morning

rituals. When passing by the local bar, a friend of mine, Bobby Zawaluk called out to me to come join him for a drink.

(Fishermen, I quickly learned, are on their own timetable). Needless to say, I had a coke, instead. We were chatting a

bit when he mentioned he would be going back out to sea early the next morning. He tried to buy me another coke,

as if to say he wanted to talk more with someone on land before heading back to sea; he pulled out a huge wad of

hundred dollar bills. When I declined, he said, “gee, I can’t even give my money away!” That was the last time I saw

him. They didn’t recover his body for several days, but the first thing of his they did recover was his wallet. I found

that so ironic. As the town began its mourning, I was driven to make a stack of abstract paintings about this

community tragedy. They were my “elegies” to the Patricia Marie and the town of Provincetown. I had become so

close to the locals during this first winter that I wanted to share my compassion for what had happened. I realized, as

I painted furiously, that I had made my first ‘body of work’ that had my own signature — not Dad’s and not Helen’s.

That was a pivotal moment that enabled me to return to NYC to resume a career in painting.

KK: Please speak to us about the recent tragedies with the Boston Marathon and how that affects you as a

Bostonian and artist.

JM: I felt sick while it was going on. I was born and raised in NYC and felt the pain when the Twin Towers went

down. I remember living in Soho when they were built and thinking how ugly they were, but when they went down, I

took it personally.

Whenever an unexplained tragedy of this nature occurs, like the Boston Marathon bombings, I suppose one’s natural

response is that of shock and horror, then anger, then grief. Never, in my life have I experienced an entire city

lockdown. It gave me real pause when I realized how palpable the nature of terror is. Our program was directly

affected by the marathon bombings, as one of our alums was thrown out of the bleachers at the finish line and is now

recovering from a broken back and two broken wrists. She says she is one of the lucky ones. She has at least a year

of physical therapy ahead of her, and without mobility in her hands, she can’t do photography (She was once a

photographer for the mayor’s office).

In Boston, people came together as quickly as they did in Provincetown and in New York City, so many years ago.

I think it is a testament about good vs. evil — evil can do a lot of damaging things, but it cannot crush the spirit. Hope

Jeannie Motherwell — “NEVER GIVE UP THE JOY AND AWE OF EXPLORATION”

Page 4

and peace and our spirit are what I like to believe we as human beings are about.

I grew up in a different time. I didn’t live under the fear of terrorism. It’s challenging now to raise children to be

innocent and yet keep them aware of the world and to be safe. I hope and pray for our world, and that it doesn’t take

a tragedy or disaster to make people come together.

KK: If you were given one wish, what would it be?

JM: I’m community-oriented. I’d like my family (daughter, stepdaughter, stepson, grandchildren) to know that life is a

gift. It’s essential to give back in some way. It might be in a small way, but it is necessary to give back, nevertheless.

KK: What’s your next project?

JM: I was recently picked up by the Quester Gallery in Greenwich, CT, where I plan to exhibit in the fall. I’m excited

because the gallery is incorporating dance, performance, poetry, and painting in its future endeavors. I have gone

back to making fairly large paintings again; perhaps another homage to something bigger than me.

KK: Thanks, Jeannie.

Aftermath, 2013, Acrylic and collage on silk, © Copyright

To see more of Jeannie Motherwell’s work: www.jeanniemotherwell.com

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Website Design by Ritual Labs LLC

Jeannie Motherwell — “NEVER GIVE UP THE JOY AND AWE OF EXPLORATION”

Page 5

by Jeannie Motherwell

Journal of the Print World, Vol. 35, Number 1, January, 2012

Robert Motherwell, Helen Frankenthaler and Cape Cod Influence the Works of

Jeannie Motherwell

Jeannie Motherwell, “Perfect Storm,” 2007, Acrylic and Collage on Canvas

In early childhood, my father and stepmother encouraged me to make drawings and paintings about what I dreamed

the night before. Like many, they often pinned my work to the refrigerator, but they also framed many of these

mementos. It was a marvelous form of validation for me and influenced my love for painting today. I have a childhood

of memories from summers spent in Provincetown, MA, a tiny fishing village and artist colony on the tip of Cape Cod.

Surrounded by artists, writers and an internationally renowned artist family (my father is Robert Motherwell and

stepmother Helen Frankenthaler), it was there where much of my creative influences were derived.

In 2009, I had a solo show in Provincetown at Lyman-Eyer Gallery, where I dedicated a series of close to 20 paintings

and collages as both a personal response and as a public memorial to the sinking, in October 1976, of the “PatriciaMarie” fishing vessel. It was headed for home to the Provincetown harbor -- its hold too heavy with scallops. The

captain and all six crew members perished.

The sinking of the Patricia-Marie happened early during my first winter in Provincetown, and for 30 years the loss

haunted me. I was 20-something, fresh out of college and the Art Students League, meeting local people, getting

around by bike, painting in my studio but mired in a deep slump at the time— I was on my own, and feeling part of a

community--something new to me since New York City, my home town, was so global.

I had befriended a dark haired fisherman named Bobby, one of the younger crew members of the Patricia-Marie. One

morning, headed to the bike trails, I passed the local bar --there he was in the door, asking if I’d join him for a beer.

After a moment’s hesitation, I joined him for a soda instead. What I remember was his smile that lit up the room and

the thick wad of $100 bills in his wallet—it must have been thousands of dollars, and he said, ‘Here I have all this

money and I can’t even give it away.’ When the boat went down, Bobby’s wallet was the first thing that emerged

before recovering his remains weeks later.

I was only at the bar for a few minutes, when I mentioned that we should get together again soon. He said he’d be

going out very early the next morning and would be gone for several days. It gave me a glimpse into his world--the

constant coming and going--from sea to land, and the dedication that it commanded.

The tragedy was a pivotal moment for me creatively. I mourned along with the community, and as I continued to

paint, an abstract subject matter began to emerge. Triangular shapes decoded were not the sailboats of my sunny

childhood, or the picturesque draggers lining the wharf, but the ghost of the Patricia-Marie.

These works began with streaks of loosely applied washes on the canvas often mimicking a raging sea; collaged

imagery of torn bits of paper, drawing and painting. Perfect Storm hints at the expressive boldness of Chinese

calligraphy. Splashes of blue surround the center of the picture; a torn piece of paper from one of my earlier boat

paintings suggests a red boat tossed by a raging sea. All elements are deliberately balanced holding the boat aloft as

it appears to be ravaged by the sea. Even if I complete the Patricia-Marie series, its sudden cataclysm will remain in

my work as memory and feeling. I liken this series to my father’s “Elegy to the Spanish Republic,” which consists of

hundreds of pieces done in memory of those who fought and died in the Spanish Civil War--a shattering event for his

generation. The boat is in my skin. After three decades of trying to name my subject, I have pulled from deep within

my core to find my own elegy conveying the unspeakable horror of that day.

www.jeanniemotherwell.com

Jeannie Motherwell jmoth@aol.com

Jeannie Motherwell

—Robert Motherwell, Helen Frankenthaler and Cape Cod Influence the Works of Jeannie Motherwell

Page 2

Provincetown Banner, August 2, 2007

Jeannie Motherwell Unlocks the Ghost of the Patricia Marie

By Susan Rand Brown

Banner Correspondent

Jeannie Motherwell, second generation Provincetown

painter, is at the top of her game as she throws red,

blue and black acrylics on a wet surface, creating

layered textures that call to mind an explosion of

pent-up anguish. To this she sparingly adds torn

collaged fragments and boat- like hieroglyphs. The

result appears as spontaneous and unpredictable as

the sea.

For her first solo show at the Lyman-Eyer Gallery,

Motherwell has created "Patricia Marie," opening with

an artist's reception at 7 p.m. on Friday, Aug. 3, and

remaining on view through Aug.

16. Lyman-Eyer is at 432 Commercial St.,

Provincetown.

Motherwell's restrained, luminous series of close to 20

paintings and collages are both a personal response

and a public memorial to the sinking in October 1976 of

the Patricia Marie as it headed for home, its hold heavy

with scallops. Its captain and all six crewmembers were

lost.

The sinking of the Patricia Marie happened early in

Motherwell's first winter in Provincetown, and for 30

years the loss haunted her. She was 20-something,

fresh out of college and the Art Students League,

meeting local, people, dancing at Piggy's, getting

around by bike, painting in her studio, after a childhood

of dappled East End summers surrounded by an artist

family (her father is Robert Motherwell and stepmother

Helen Frankenthaler, icons of abstract expressionism),

she was on her own, and feeling like a townie.

She had made a friend of dark haired fisherman Bobby

Zawalick, one of the younger crew members of the

Patricia Marie. She remembers the morning when she

passed the Foc'sle (a popular bar in the town center,

now the location of the Squealing Pig) headed to the

bike trails; there was Zawalick in the door, asking if

she'd join him for a beer. After a minute's hesitation

she’d joined him for a soda. What she remembers is his

"smile that lit up the room," and the thick wad of $100

bills in his wallet: "It must have been thousands of

dollars; and he said, 'Here I have all this money and I

can't even give it away.' When the boat went down, the

wallet was the first thing found belonging to Bobby

Zawalick."

"I was only there for a few minutes," she says, "and

when I mentioned that we should get together again

soon, he said he'd be going out again early the next

morning, and be gone for several days. It gave me a

glimpse into his world, the constant coming and going,

at sea, at land, the dedication."

PHOTO BY JAMES BANKS

Jeannie Motherwell, who will open a show on Friday, is

shown here in her studio

For Motherwell the tragedy was

a creative turning point. She mourned along with the

community, and as she continued to paint, she located

an abstract subject matter that came from her, even

though it took several decades to decode the small

abstract triangular shapes in her collages. Not the

sailboats of her sunny girlhood her friends imagined, or

the picturesque draggers lining the wharf, but the ghost

of the Patricia Marie. In Motherwell's "Abyss," streaks of

loosely applied red washes into a raging black sea. A

tornado-like black cloud hovers over in the right corner;

as a blue rectangle seems to fall into the sea, the red

sky parts slightly to reveal the shape of a white hull

barely skimming the horizon line, as if the paint itself is

hungry for a miracle.

The abstraction "Center Stage" has the expressive

boldness of Chinese calligraphy. Splashes of black that

could be boats hug the center of the picture; a torn

piece of paper from one of Motherwell's earlier boat

paintings forms a third image of a boat tossed by a

raging sea. All elements are beautifully balanced, as if

to hold the boat aloft even as it is ravaged by the sea.

Motherwell thinks that even after she completes the

Patricia Marie series, its sudden cataclysm will remain

in her work as memory and feeling. She likens her

series to her father Robert Motherwell's "Elegy to the

Spanish Republic," consisting of hundreds of pieces

done in memory of those who fought and died in the

Spanish Civil War, a shattering event for Robert

Motherwell's generation. "The boat is in my skin," she

says. After three decades of trying to name her subject,

Motherwell pulled from deep within her core and

emerged with her own elegy conveying the

unspeakable horror of that day.

by Necee Regis

American Airlines 'American Way,' December 1, 2005

Sea Change

The roster of creative types who've passed through or

lived in this town since painter Charles Hawthorne

founded one of the first art colonies in the United States

there in 1899 reads as a veritable who's who of the

international cultural elite. It begins with Hawthorne and

the American Impressionists, continues through

Abstract Expressionist masters Franz Kline, Helen

Frankenthaler, and Robert Motherwell, and includes

painters Milton Avery, Marsden Hartley, Edward

Hopper, Jackson Pollock, and Mark Rothko, as well as

writers Eugene O'Neill, John Dos Passos, Tennessee

Williams, Truman Capote, and Norman Mailer. In fact,

you may catch a glimpse of Mailer, who still lives in

town, walking briskly along Commercial Street with the

morning paper tucked beneath his arm.

Poet Stanley Kunitz, winner of both the Pulitzer prize

and the National Book Award and a two-time United

States poet laureate, first visited Provincetown in the

1920s. While walking the beach, he encountered

Hawthorne, who was teaching a group of women

students bedecked in long skirts and sunbonnets.

Twenty years later, Kunitz returned to Provincetown to

spend a summer there withhis wife, painter Elise Asher.

They've done the same every summer since, often

staying into the fall before returning to their home in

New York City.

Kunitz muses on his time spent in Provincetown in his

new book, The Wild Braid: A Poet Reflects on a

Century in the Garden. It includes his thoughts on the

creative process, gardening, and the harmony of the

life cycle, as well as 12 poems, color photographs, and

conversations with his assistant, Genine Lentine.

"Fall is a beautiful time in Provincetown," he writes

in The Wild Braid. "Those great blue skies! And there's

a certain fragrance in the air out of the brine and the

fallen leaves. It is certainly one of the beautiful spots on

earth . . . I do not know of a place that is comparable to

it, with its vast seascapes, the glorious Cape light, the

air that flows in from the sea, and a community of

deeply engaged artists."

I felt it was important to have a role in starting a

community of artists," Kunitz says. "That, to me,

seemed an essential creative necessity if the town was

to be more than just a vacation place."

Kunitz celebrated his 100th birthday this summer in

Provincetown, in the garden he's been tending since he

bought his home more than 40 years ago. Streams of

friends passed through to offer good wishes and cheer.

(Elise Asher passed away last year.)

"It's curious. I remember coming here from a farm in

Connecticut," Kunitz tells me. "I was hearing about the

community of artists, writers, and painters, and the next

thing I knew, I was here, and I started my garden here,

and I've never regretted it."

Kunitz set out to create a community, and on a bright

summer day, on this spit of land surrounded by the sea,

the community returned to honor him.

JEANNIE MOTHERWELL spent every summer of her

childhood in Provincetown with her father, the

internationally renowned painter Robert Motherwell,

and her equally well-known stepmother, Helen

Frankenthaler. In the late 1950s, their circle of friends

included luminaries in the fields of painting, writing, and

psychology

"He pulled a wad of $100 bills from his pocket and said,

'I have all this money and I can't give it away,' "

Motherwell remembers.

The next day his boat the Patricia Marie, sank. All that

was found was his wallet. Filled with emotion and a

sense of loss to the community, Motherwell began a

series of abstract paintings and collages of draggers

(fishing vessels), which were bought by both local

fishermen and art collectors.

"It was my first sense of finding my identity in painting,"

she says.

In the past decade, she's used collage, digital

photography, painting, and text to create complex,

subtle works that evoke the Cape's Province Lands.

The images straddle abstraction and reality.

She now lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts, but

returns to Provincetown every summer to exhibit her

work and find new inspiration. When asked if it's hard to

follow in her parents' larger-than-life footsteps, she

smiles.

"My audience is different than Dad and Helen's," she

says. "It took me a while to realize I'm not trying to

change the world with art; I'm trying to use what I know

to make good pictures."

While their parents worked in their studio, Jeannie and

her sister played on the beach with the children of other

artists and writers.

"Dad's theory was that this was better than camp," she

says. Motherwell, 52, was raised in a world where

creativity and psychoanalysis were part of her daily

routine.

"We'd talk about our dreams every morning," she says.

"Then, Helen and Dad would ask us to write something

and make a drawing out of it. We had no coloring

books; nothing was premade. We were asked at an

early age to think about our thoughts and emotions."

A seminal moment in her artistic development occurred

when Motherwell moved to Provincetown full-time in the

late 1970s, when she was in her 20s. As she was riding

her bike through town, a local fisherman waved and

asked her to join him for a drink.

A Provincetown Reading List

Provincetown: Stories from Land’s End, by Kathy Shorr

My Provincetown, Memories of a Cape Cod Childhood, by Amy Whorf McGuiggan

Land’s End, A Walk in Provincetown, by Michael Cunningham

The Wild Braid: A Poet Reflects on a Century in the Garden, by Stanley Kunitz with Genine Lentine

Sea Change

page 2

by Brenner Thomas

excerpted from

Provincetown Magazine

Vol. 27, Issue 12, June 24-30, 2004

the Seen and the

Unseen

Jeannie Motherwell

and Deborah Barlow

Show New Work

In “Bay 1( for HF)” by Jeannie Motherwell, the horizon line breaks down. Or

does the sky become the sea?

It is ironic that abstract art, a

category described as one of the

freest and most open forms of

expression, is often the most difficult

to pin down. How do we begin to

understand an image when we don’t

know exactly what we’re looking at?

How do you apply language to

something that is often a nonverbal

enterprise?

Part of the confusion stems from the

fact that abstract art isn’t one thing;

the aesthetic can be applied in

varying degrees. The work of early

abstractionists—Picasso and earlier

Cezanne—were literal abstractions:

the distillation of real objects,

landscapes etc. into more basic,

essential forms. The artistic process

involved reducing more traditional

imagery into something else:

buildings into rectangles, faces into

circles, a mountain into triangles for

instance.

Later, in the high Formalism of the

mid-20th century, the demigods of

abstraction like Pollock and

Kandinsky, made images that made

no reference to the “real” world.

Their splatters of paint and line and color were nothing more or less than

visual. They were not meant to be “read” or “understood” beyond the

pigments of the picture plane itself. The triangle no longer stood for a

mountain. The triangle was a triangle. In short, what you saw is what you

got.

The work of Jeannie Motherwell and Deborah Barlow, two contemporary

artists whose work will be showcased in a two-(wo)man show at the LymanEyer Gallery opening Friday, June 25, falls somewhere in between. Neither

considers themselves a realist but nevertheless the real world plays a crucial

yet equally specific role in both of their work.

Later, in the high Formalism of the mid-20th century, the demigods of

abstraction like Pollock and Kandinsky, made images that made no

reference to the “real” world. Their splatters of paint and line and color were

nothing more or less than visual. They were not meant to be “read” or

“understood” beyond the pigments of the picture plane itself. The triangle no

longer stood for a mountain. The triangle was a triangle. In short, what you

saw is what you got.

The work of Jeannie Motherwell and Deborah Barlow, two contemporary

artists whose work will be showcased in a two-(wo)man show at the LymanEyer Gallery opening Friday, June 25, falls somewhere in between. Neither

considers themselves a realist but nevertheless the real world plays a crucial

yet equally specific role in both of their work.

Jeannie Motherwell, a longtime practitioner of collage, has with her new

work gotten back to her roots: painting. The new series of small images,

inspired by a catalogue of work by her stepmother that were titled after

Provincetown locations, is her most painterly to date. Having spent much

of her childhood here with her parents, icons of American art Robert

Motherwell and Helen Frankenthaler, Jeannie says her stepmother’s images

spawned a nostalgia and sentimentality toward Provincetown. It’s been nearly

half a decade since Jeannie sold her Provincetown studio, where she had

worked off and on for thirty years. Seeing her stepmother’s renderings of the

Provincelands encouraged Jeannie to revisit the landscapes of the Outer

Cape in her work. She calls it “an homage to Provincetown and the view out

the window” from her studio here.

The window, as metaphor and an image, is important to Jeannie. Last time

Provincetown Magazine spoke to her two years ago she was on the verge of

revealing a group of pieces entitled the Window series, collages of realistic

digital images and abstract design in paint framed in deep shadow boxes.

She had created views into impossible yet poetic landscapes, collaborations

of paint and photography. She called the window in that interview her “symbol

of looking into how I see the world.”

Jeannie likes to work in series. Considering that creative possibilities for an

abstractionist are endless, she says this gives her something “to rely on.”

Though the new “Provincelands” series represent considerable formal

changes in Jeannie’s work—they are, for instance, all works on paper which

make use of a good deal more color—windows still influence her. Gone are

the deep shadow box frames, which have been replaced by a wide thick

matting. “I wanted to frame them the way you’d frame a photograph,” Jeannie

explains. But the effect is window-like, the white space drawing you into the

world of the painting which seems beyond the plane of the frame, as in “Bay I

for HF.”

But you’re never really sure what that world is. The line between abstraction

and realism in Jeannie’s work is always tenuous. In “Bay,” this line is

literalized between the digital image of the dune on the right and the painterly,

impressionistic sky above. Here, the realistic and the nonrepresentational

meet at the horizon line. But this system breaks down as the image advances

right to left, the acrylic paint of the sky encroaching on the land in cautious

blue steps. Has the sky bled? Or is it water? You can’t know anything for sure

besides understanding that Jeannie’s work never totally reveals itself. It’s the

nature of the aesthetic. She says she’s always trying to find the fine line

between abstraction and realism. “Painters that can do that just really hit me

in the gut,” she says. “That’s the kind of look I am always seeking.”

the Seen and the Unseen

page 2

Beyond the Windows: A Conversation with Jeannie Motherwell

By Peter Alson

Provincetown Arts, 1999

Jeannie Motherwell and I both spent our childhood summers in Provincetown, and knew each other slightly, yet didn't

become good friends until much more recently. I'm not sure exactly why that's so, but we were both shy as children,

and beyond that shared a certain unmetabolized weight of artistic expectation that might have made a friendship

uncomfortable.

In Jeannie's work, which combines painting with photographs, appropriated images and text, there is play between

shadow and light, water and boats, doorways and windows, that sometimes shows a glimpse of what might be

Provincetown harbor, but more often is an obscure, sunlight-suffused window into a world that we can't quite see.

Almost always, the work feels hopeful, as if there were something beyond those windows, as if perhaps there is a

person inside hiding who is now ready to come out.

PETER ALSON: You and I both have father figures who were and are huge presences in the literary and art worlds,

for you it was your dad, Robert Motherwell, and for me it's my uncle, Norman Mailer. You became a painter; I became

a writer.

JEANNIE MOTHERWELL: Imagine that!

PA: Are we crazy? Or just masochistic?

JM: I don't worry about that anymore. It's too late now. But the fact is I tried to give up painting for many years. Many

years. I think wanting to become a painter was a natural impulse, growing up with and being around my father and

stepmother Helen [Frankenthaler; married from 1958-1970]. They were my role models. But I also think when I was

younger I worried too much about making it in the art world, because they had already done so. I just don't anymore. I

feel like I have to paint now whether I'm successful or not. What about you?

PA: I think it's pretty similar. I started writing because I didn't know any better. I was 17 and I was suddenly seized by

the urge to write a story.

JM: That's the age I started painting!

PA: I think inwardly I'd always fought against becoming a writer in the way you resist any family business, but, as you

say, there's a strong gravity exerted by having someone close to you who is successful and famous and obviously

enjoying what they do.

JM: I really fell in love with painting when I was in college, and finally understood why Dad and Helen loved it so. I

remember writing Dad letters all the time from college about the feeling. He was encouraging but also told me that it

was a lousy business. Still, he thought I had the talent and the "bug."

PA: So he was supportive?

JM: Very supportive. But to have him come into your studio was a little unnerving. He'd walk in and say, "That's very

good. Don't touch it!" Or, "That's very good. It just gets past tacky."

PA: That must have been somewhat difficult.

JM: Well, I learned some things from those kind of criticisms but it also started me looking at my own work with his

eye too much. On the other hand, it enabled me to understand his work really well. I can usually identify his best work

before someone else, because I understood him and his process so well. But I think that's where I wasn't so sure

about my own identity. I think that's probably why I quit painting.

PA: You did? I stopped writing for a while.

JM: For the same reason?

PA: I think so—if identity means knowing why you're doing something. I know when I came back to writing after about

a year, it felt like I was making a choice, which gave me a different feeling about what I was doing. How long did you

stop painting?

JM: Fourteen years.

PA: Wow, 14 years! That's an incredibly long time. That's not just a break.

JM: I was thinking I'd absolutely never do it again. I was married, had a child, and we were living a different kind of

life. I thought, "Oh, this is much better." And it wasn't that I didn't have the time to paint, I just felt I was learning more

watching my child develop.

PA: What changed?

JM: It's funny, I had taken my husband's name when we got married, but you can't ever really get rid of your name,

so when I got divorced I took my name back because I thought, This is ridiculous. This is who I am.

PA: And you started painting again?

JM: No. Not right away. But one day a friend of mine asked me when I was going to start painting again, and I said,

"What do you mean?" And he said, "Why don't you just have some fun?" And so I tried to. I started making cards and

sending them to people, and it just sort of expanded from there. I began putting things on canvas, and the next thing I

knew I was painting.

I don't think I knew you could have fun when you painted. I grew up thinking one couldn't say anything unless it was

profound. Dad and Helen were already famous. That was the only way I knew them. I didn't see them starting out or

struggling or what they went through to get there. I just thought you already had to know what you were doing. So it

wasn't fun. It was really, really hard, and I was wrapped up in trying to find my own identity. But now I find it so much

fun—because I'm inspired and I feel like I know who I am.

PA: Your use of the form of collage is interesting to me, as a fellow child of divorce, because in collage you're putting

disparate fragments together and trying to make sense of them, making a whole out of broken pieces.

JM: I think that's very true. Not only that, but growing up in a house like Dad's or Helen's or Renate's [Renate

Ponsold, Motherwell's fourth wife, of 19 years, whose photographs are featured in this issue] was like walking through

museums all the time. Everything was an object d'art, placed in a certain way, and you spent all your time looking

around, and if you grow up in that you can't help but constantly notice how things go together. Also, Dad used to do

things like wake up and decide to rearrange the paintings in the room, so all of a sudden everything looked different,

and it had the same effect as collage. I think that's what drew me to it. The control of pushing things around, and the

added surprise of what you get when you do that. So when you picked up on the idea of the different parts of your life

being put together, that's really what it's about for me.

PA: In writing the only time things truly are alive for me is when I'm making discoveries and connections, when I'm

being surprised, so when you use the word "surprise" it has resonance for me. Also the idea of making connections.

When I think of collage I think of making connections between images that might not logically go together, it's more of

an instinctive thing. In the text that you use in some of your collages—unattributed text, I might add...

JM: Plagiarism [laughs], total plagiarism.

PA: ...the word "connection" keeps coming up and it jumps out at me. Was that something you were thinking about

when you picked out those pieces of text?

JM: They actually come from a poem a friend of mine wrote about 25 years ago, and he happened to send it to me,

and I started cutting it up, and then asked him if he would mind.

PA: Who is this?

JM: An artist and writer friend of mine named Jim Banks. I call him "Word Man." The poem really seemed to fit in my

pictures, so I took it and went with it.

PA: In the piece Eyes Look Take a Look, you use a photograph of your daughter Rebecca's eyes on top of a

woman's torso by Titian.

Jeannie Motherwell — Beyond the Windows

Page 2

JM: All the things my daughter's going through growing up—the love, passion, innocence, pain—and what I

experience myself as a woman, have parallels as well as separations, so there are connections but they're different.

It's about the play between the two, the contrasts, that I was working with.

PA: Do you still look at things through your dad's eyes, either after you've painted something or during the process?

JM: Well, I guess at this point I don't have to worry about what he would think anymore. I'm happy with what I'm

painting, and whether someone else likes it or not, I know that the work is me and in that sense real and true. I know

Dad would believe in that. Would I be able to say this if he were still alive? I don't know. But I think if you are being

honest and you are being true, that's really all you can do. For some of us it just takes a little longer to get there than

for others.

Peter Alson is the author of the memoir Confessions of an Ivy League Bookie, reviewed inProvincetown Arts '96. His

writing has appeared in a wide range of national magazines, including Esquire and Playboy

.

Jeannie Motherwell — Beyond the Windows

Page 3

3 Friends of Winter, Panel 1, 2015, Acrylic on Claybord, 48" x 66"

3 Friends of Winter, Panel 2, 2015, Acrylic on Claybord, 48" x 66"

3 Friends of Winter, Panel 3, 2015, Acrylic on Claybord, 48" x 66"

3 Friends of Winter (3 panels), 2015, Acrylic on Claybord, 48" x 108"

Sass, 2015, Acrylic on Claybord, 48" x 67"

Jeannie Motherwell, A Sacred Trade, 2015, Acrylic on canvas, 48" x 67"

Bearing, 2014, Acrylic on canvas on board, 36" x 51"

Every Swarm, 2014, Acrylic on Claybord, 48" x 67"

The Full Monty, 2015, Acrylic on Claybord, 48" x 67"

Recurring at Every Stage, 2015, Acrylic on canvas, 48" x 67"

Night Rhythms, 2014, Acrylic on canvas on board, 43" x 66"

Spawn, 2014, Acrylic on board, 48" x 67"

In the Wake, 2014, Acrylic on Claybord, 14" x 11"

Big Bang, 2013, Acrylic & pastel on board, 48" x 67"